Abstract

VerifyThis 2015 was a one-day program verification competition which took place on April 12th, 2015 in London, UK, as part of the European Joint Conferences on Theory and Practice of Software (ETAPS 2015). It was the fourth instalment in the VerifyThis competition series. This article provides an overview of the VerifyThis 2015 event, the challenges that were posed during the competition, and a high-level overview of the solutions to these challenges. It concludes with the results of the competition and some ideas and thoughts for future instalments of VerifyThis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

VerifyThis 2015 took place on April 12th, 2015 in London, UK, as a one-day verification competition in the European Joint Conferences on Theory and Practice of Software (ETAPS 2015). It was the fourth edition in the VerifyThis series after the competitions held at FoVeOOS 2011, FM2012 and Dagstuhl (Seminar 14171, April 2014).

The aims of the competition were:

-

to bring together those interested in formal verification, and to provide an engaging, hands-on, and fun opportunity for discussion;

-

to evaluate the usability of logic-based program verification tools in a restricted setting that can be easily repeated by others.

This article provides an overview of the VerifyThis 2015 event, the challenges that were posed during the competition, and a high-level overview of the solutions to these challenges. While we do not provide guidance on how to perform an in-depth evaluation of the participating tools, we highlight the main tool features that were used in solutions. We conclude with the results of the competition, and some ideas and thoughts for future instalments of VerifyThis.

Before the VerifyThis competitions (and the related online VS-Comp competitions) were launched, verification systems were only evaluated according to the size of the completed project. However, due to the size and complexity of the verification efforts, such experiments could not be reproduced. Furthermore, the efficiency of the verification could not be measured, as they were carried out over prolonged periods of time, by multiple people, with different background, and without proper time accounting.

VerifyThis, in contrast, shifts the measurement to efficiency. Typical challenges in the VerifyThis competitions are small but intricate algorithms given in pseudo-code with an informal specification in natural language. Participants have to formalise the requirements, implement a solution, and formally verify the implementation for adherence to the specification. There are no restrictions on the programming language and verification technology used. The time frame to solve each challenge is quite short (between 45 and 90 min), so that anyone can easily repeat the experiment. Thus, the competition setup can be easily reproduced by anyone, the challenges are self-contained, time is controlled, and establishing the relation between specification and implementation is straightforward.

The correctness properties which the challenges present are typically expressive and focus on the input–output behaviour of programs. To tackle them to the full extent, some human guidance within a verification tool is usually required. At the same time, considering partial properties or simplified problems, if this suits the pragmatics of the tool, is encouraged. The competition welcomes participation of automatic tools as combining complementary strengths of different kinds of tools is a development that VerifyThis would like to advance.

Submissions are judged for correctness, completeness, and elegance. The focus includes the usability of the tools, their facilities for formalising the properties, and providing helpful output. As each solution depends on different tools and different participants, creativity is an important factor in the competition. However, correctness and completeness are relatively objective criteria, and one can estimate approximately how close the team is to a completely verified solution of the challenge.

Experiences with earlier editions of VerifyThis have shown that participation leads to insight in: (i) missing tool features, (ii) useful features, which helped other teams to develop their solutions, and (iii) tool features which are awkward to use and need further improvement and testing. It is difficult to quantify the concrete effects on tool development, but when judging, we see that insights obtained during earlier competitions actually lead to new tool developments. Moreover, the VerifyThis challenges are also used as verification benchmarks outside of the competition.

1.1 VerifyThis 2015

VerifyThis 2015 consisted of three verification challenges. Before the competition, an open call for challenge submissions was made. As a result, six challenges were submitted, of which one was selected for the competition (see also Sect. 5.5 for more details about this call and the selection criteria). The challenges (presented later) provided reference implementations at different levels of abstraction. For the first time, one of the challenges centered around concurrency.

Fourteen teams participated (Table 1). Teams of up to two people were allowed and physical presence on site was required. We particularly encouraged participation of:

-

student teams (this includes PhD students);

-

non-developer teams using a tool someone else developed;

-

several teams using the same tool.

Teams using different tools for different challenges (or even for the same challenge) were welcome.

As in the VerifyThis 2012 competition, after the competition, a post-mortem session was held, where participants explained their solutions and answered the judges questions. In parallel, the participants used this half-day session to discuss details of the problems and solutions among each other.

The website of the 2015 instalment of VerifyThis can be found at http://etaps2015.verifythis.org/. More background information on the competition format and the rationale behind it can be found in [10]. Reports from previous competitions of similar nature can be found in [2, 8, 15], and in the special issue of the international journal on software tools for technology transfer (STTT) on the VerifyThis competition 2012 (see [11] for the introduction).

1.2 Rules

To ensure that the competition proceeded smoothly, the following rules were established:

-

1.

The main rule of the competition is: no cheating is allowed. The judges may penalise or disqualify entrants in the case of unfair competition behaviour and may adjust the competition rules to prevent future abuse.

-

2.

Solutions are to be submitted by email.

-

3.

Submissions must state the version of the verification system used (for development versions, internal revision, time-stamp, or similar unique id).

-

4.

It is permitted to modify the verification system during the competition. This is to be noted in the solution(s).

-

5.

All techniques used must be general-purpose, and are expected to extend usefully to new unseen problems.

-

6.

Internet access is allowed, but browsing for problem solutions is not.

-

7.

Involvement of other people beyond those on the team is not allowed.

-

8.

While care is taken to ensure correctness of the reference implementations supplied with problem descriptions, the organisers do not guarantee that they are indeed correct.

2 Challenge 1: Relaxed Prefix (60 minutes)

This problem was submitted by Thomas Genet, Université de Rennes 1, in response to the open call for challenges.

2.1 Verification task

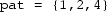

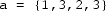

Verify a function

determining if a list

(for pattern) is a relaxed prefix of another list

. The relaxed prefix property holds iff

is a prefix of

after removing at most one element from

.

Examples

-

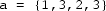

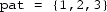

is a relaxed prefix of

(standard prefix)

-

is a relaxed prefix of

(remove 2 from pat)

-

is not a relaxed prefix of

Implementation notes One may implement lists as arrays, e.g., of integers. A reference implementation is given below. It may or may not contain errors.

2.2 Comments on solutions

Eleven teams (Verifast, Why3, AutoProof, KeY, Dafny (3 teams), mCRL2, F*, KIV, and VerCors) submitted a solution to this challenge. Difficulties that had been encountered by the participants were mainly at the specification level: getting the prefix definition correct, and making sure that all cases were covered in the postconditions. In particular, several teams forgot the case, where the length of the array was less than the length of the prefix, or where the method returned false. In the overall evaluation, the solution provided by the Why3 team was the only one to obtain full marks from the judges.

During the verification, the main challenge was to find an appropriate instantiation for the existential quantifier. Different solutions for this were used: the Why3 team brought the specification into a particular syntactical shape that enabled the SMT solver to guess the instantiation (in a post-competition solution, this trick was replaced with an explicit assertion); the KeY team and the AutoProof team used an explicit return value, which avoided the need for existential quantification (witness computed by the program); Tim Wood, using Dafny, used an explicit hint in the form of a trigger annotation; the KIV team tried to address this by manual instantiation; while Robert Kelly and Marie Farrell, using Dafny, provided a recursive definition of a relaxed prefix.

2.3 Future verification tasks

For those who had completed the challenge quickly, the description included a further challenge, outlined below. No submissions attempting to solve the advanced challenge were received during the competition.

Verification task: Implement and verify a function

returning whether

contains

in the above relaxed sense, i.e., whether

is a relaxed prefix of any suffix of

.

3 Challenge 2: Parallel GCD (60 minutes)

Various parallel algorithms for computing the greatest common divisor

exist (cf. [23]). In this challenge, we consider a simple Euclid-like algorithm with two parallel threads. One thread performs subtractions of the form

, while the other thread performs subtractions of the form

. Eventually, this procedure converges on the GCD.

In pseudo-code, the algorithm is described as follows:

3.1 Verification task

Specify and verify the following behaviour of this parallel GCD algorithm:

- Input::

-

two positive integers

and

- Output::

-

a positive integer that is the greatest common divisor of

and

Synchronisation can be added where appropriate, but try to avoid blocking of the parallel threads.

Sequentialisation If a tool does not support reasoning about parallel threads, one may verify the following pseudo-code algorithm:

3.2 Comments on solutions

Five teams (Verifast, mCRL2, KIV, CBMC, and VerCors) submitted a solution to the concurrent version of this challenge; six teams [Why3, AutoProof, KeY, Dafny (2 teams) and F*] submitted a solution to the sequentialised variant of the challenge.

The solutions to the concurrent version of the challenge were all very different in spirit. The submissions assumed varying degrees of atomicity. In some formalisations, atomic operations were the individual loads and stores, in others—the loop body, yet in others—the evaluation of the loop condition followed by the loop body. All formalisations assumed sequential consistency though. All were also in some aspect partial.

Bart Jacobs (VeriFast) developed a fine-grained concurrent solution, showing the specified postcondition but assuming the necessary properties of the mathematical GCD predicate. The solution uses “shared boxes”, which integrate rely-guarantee reasoning into the separation logic of VeriFast. Despite its significant complexity, the solution was judged as the best among the submitted ones.

Closely following was a solution by Jan Friso Groote with mCRL2. mCRL2 and CBMC are both bounded verification tools and thus only checked correctness within limits on the range of input parameters resp. the loop unwinding depth. The mCRL2 solution elegantly used quantifiers to specify the GCD postcondition.

The KIV team used a global invariant proof approach but got stuck on the necessary GCD properties (while later realising that they actually could have used GCD lemmas from the KIV libraries). Finally, the VerCors team submitted a solution, making use of the recently added support for parallel blocks, but proving absence of data races only. Post-competition they extended this to a full solution.

The judges were also impressed by the attempt of the AutoProof team. In addition to proving correctness of the sequentialised algorithm, they almost succeeded in proving termination of the sequential version, assuming an appropriate fairness condition.

The KIV team was not the only team that experienced that well-developed libraries can help while solving a challenge. The Why3 team solved the sequentialised version of this problem within 15 min, because their tool has a powerful library with the necessary GCD lemmas, while Rustan Leino (Dafny) struggled with this (sequentialised) challenge because of the lack of appropriate Dafny libraries.

After the competition, Rustan Leino developed a Dafny solution for the concurrent program, by writing a program that explicitly encoded all the possible interleavings between the different threads, while using explicit program counters for each thread.

4 Challenge 3: Dancing Links (90 minutes)

Dancing links is a search technique introduced in 1979 by Hitotumatu and Noshita [12] and later popularised by Knuth [16]. The technique can be used to efficiently implement a search for all solutions of the exact cover problem, which in its turn can be used to solve Tiling, Sudoku, N-Queens, and other related problems.

Suppose

points to a node of a doubly linked list; let

and

point to the predecessor and successor of that node. Then the operations

remove

from the list. The subsequent operations

will put

back into the list again. Figure 1 provides a graphical illustration of this process.

4.1 Verification task

Implement the data structure with these operations, and specify and verify that they behave in the way described above.

4.2 Comments on solutions

Several participants reported that this had been a difficult challenge, and in particular, it had taken them time to understand the full details of the intended behaviour. Ten solutions [Verifast, Why3, AutoProof, KeY, Dafny (2 teams), mCRL2, F*, KIV, and CBMC] to the challenge were submitted. During the competition, the organisers clarified that the main challenge was in managing the remove and unremove—several elements can be removed and unremoved, but they must be unremoved in reverse order (otherwise, the references are not maintained). Furthermore, the list should either be considered circular or removal of the first and last elements not allowed.

Rustan Leino (using Dafny) was the only one to address this challenge completely within the allocated time. He reported that he found it much easier to reason about the list using integers and quantifiers rather than using recursively defined predicate(s). This observation was confirmed by the Why3 team after completing a post-competition solution.

The AutoProof team welcomed the Dancing Links challenge, as it was ideally suited for demonstrating their recently developed technique called semantic collaboration [21]. Semantic collaboration is intended to improve reasoning about objects collaborating as equals to maintain global consistency (rather than doing so in a strictly hierarchical manner).

5 Results, statistics, and overall remarks

We conclude this report with various data points and summaries of results.

5.1 Awarded prizes and statistics

The judges unanimously decided to award prizes as follows:

-

Best team: team Why3—Jean-Christophe Filliâtre and Guillaume Melquiond;

-

Best student team: team KIV—Gidon Ernst and Jörg Pfähler;

-

Distinguished user-assistance tool feature—awarded to two teams:

-

Why3 for the lemma library (as demonstrated by its use in the competition);

-

mCRL2 for a rich specification language in an automated verification tool.

-

-

Best challenge submission: Thomas Genet for the Relaxed Prefix problem, which was used as Challenge 1 in the competition.

-

Tool used by most teams: Dafny.

The best student team received a 500 Euro cash prize donated by our sponsors while the best overall team received 150 Euros. Smaller prizes were also awarded for the best problem submission and the distinguished user-assistance tool feature.

5.2 Statistics per challenge

-

Relaxed prefix 11 submissions were received, of which only the submission by Jean-Christophe Filliâtre and Guillaume Melquiond (Why3) was judged as correct and complete.

-

Parallel GCD 11 submissions were received, of which the submission by Bart Jacobs (Verifast) was judged as correct and most complete. Six of the submitted solutions were restricted to the sequential version of the challenge.

-

Dancing Links 10 submissions were received, of which only the submission by Rustan Leino (Dafny) was judged as correct and complete.

5.3 Travel grants

The competition had funds for a limited number of travel grants for student participants. A grant covered the incurred travel and accommodation costs up to EUR 250 for those coming from Europe and EUR 500 for those coming from outside Europe. Evaluation criteria were qualifications (for the applicant’s career level), need (explained briefly in the application), and diversity (technical, geographical, etc). Six travel grants were awarded.

5.4 Post-mortem sessions

Two concurrent post-mortem sessions were held on the afternoon of the competition (stretching to the day after the competition, given the large number of participants). These sessions were much appreciated, both by the judges and by the participants. It was very helpful for the judges to be able to ask the teams questions in order to better understand and appraise their submissions. Concurrently, all other participants presented their solutions to each other. We would recommend such a post-mortem session for any on-site competition. In future editions of the competition, we intend to extend this aspect of the event as participants reported the time used as invaluable, providing lively discussions about the challenges, gaining knowledge about tools through presenting challenge solutions to each other and exchanging ideas about future tool developments and solution strategies.

5.5 Soliciting challenges

After much discussion at the previous competition, on how to extend the problem pool and tend better to the needs of the participants, we issued a call for challenges to extend the problem pool. The call stipulated that:

-

A problem should contain an informal statement of the algorithm to be implemented (optionally with complete or partial pseudo-code) and the requirement(s) to be verified.

-

A problem should be suitable for a 60–90 min time slot.

-

Submission of reference solutions is strongly encouraged.

-

Problems with an inherent language- or tool-specific bias should be clearly identified as such.

-

Problems that contain several subproblems or other means of scaling difficulty are especially welcome.

-

The organisers reserve the right (but no obligation) to use the problems in the competition, either as submitted or with modifications.

-

Submissions from (potential) competition participants are allowed.

We received six suggestions for challenges, and decided that one was suited for use during the competition. This challenge was practical, easy to describe to participants, suitable in duration for the competition, and could be easily adapted to suit different environments. However, even though we decided not to use all of the submitted challenges directly,Footnote 1 the call for submissions provided inspiration for further challenges as well as insight in what people in the community consider interesting, challenging and relevant problems for THE state-of-the-art verification tools.

5.6 Session recording

This year, for the first time, the organisers encouraged the participants to record their desktop during the competition (on a voluntary basis). The recording would give insight into the pragmatics of different verification systems and allow the participants to learn more from the experience of others deriving a solution. The organisers provided a list with recording software suggestions, though so far only a solution for Linux (Freeseer) could be successfully tested. The main criteria are free availability, ease of installation, and low CPU load.

In general, participants agreed that recording could provide useful information, but, as far as we know, only the KIV team actually made a recording.

5.7 Related events

VerifyThis 2015 is the 4th event in the VerifyThis competition series. Related events are the Verified Software Competition (VSComp, http://vscomp.org) held online, the Competition on Software Verification (SV-COMP [3], http://sv-comp.sosy-lab.org) focusing on evaluating systems in a way that does not require user interaction,Footnote 2 and the RERS Challenge ([9], http://www.rers-challenge.org), which is dedicated to rigorous examination of reactive systems, using different technologies such as theorem proving, model checking, program analysis, symbolic execution, and testing.

VerifyThis is also a collection of verification problems (and solutions). Its counterpart is VerifyThus (http://verifythus.cost-ic0701.org/)—a distribution of deductive verification tools for Java-like languages, bundled and ready to run in a VM. Both were created with support from COST Action IC0701.

A workshop on comparative empirical evaluation of reasoning systems (COMPARE2012 [13]) was held at IJCAR 2012 in Manchester. Competitions were one of the main topics of the workshop.

5.8 Judging criteria

Limiting the duration of each challenge assists the judging and comparison of each solution. However, this task is still quite subjective and hence difficult. Discussion of the solution with the judges typically results in a ranking of solutions for each challenge. In future editions of the competition, we envisage that each team would complete a questionnaire for each challenge on submission. This would assist the judging and would also encourage teams to reflect on their solutions.

Based on earlier experiences, the criteria that were used for judging were:

-

Correctness is the formalisation of the properties adequate and fully supported by proofs? In essence, this is a two-valued criterion, and a correct formalisation is a must to consider the solution.

-

Completeness are all tasks solved, and are all required aspects covered? The judges used a rough estimate how much of the proof was finished to come to a complete solution. For example, if a team can show a full solution developed the next day, this is used an indication of being relatively close to the full solution within the time frame of the competition.

-

Readability can the submission be understood easily, possibly even without a demo? Clearly, this is a more subjective criteria, but as all the judges participated in the post-mortem session, and have ample experience with formal specification; therefore, the number of questions about the formalisation is a good indication for this.

-

Effort and time distribution what is the relation between time expended on implementing the program vs. specifying properties vs. proving? The post-mortem session was used to obtain information about this.

-

Automation how much manual interaction is required, and for what aspects? Again, the post-mortem session was used to obtain information about this.

-

Novelty does a submission apply novel techniques?Footnote 3 Teams that used novel features are usually eager to provide this information during the post-mortem session.

A novelty for VerifyThis this year was the inclusion of a judge with a background in software model checking (the fourth author of this paper). He observed that the participants could have been more critical, reflecting on their solutions. To use the tools, often expert knowledge is necessary, and the tools are not very good at providing feedback when a proof attempt fails. For future competitions, he felt that the most interesting aspect would be new insights, leading to further improvements to the tool. This aspect was also mentioned by some of the competition participants. It will be worthwhile investigating what novelties have resulted from earlier competitions.

5.9 Post-competition discussion

Directly after the competition, before starting the post-mortem session, a plenary discussion was held to gather the opinion of the participants about the organisation of future competitions. The following topics were discussed:

- Challenges :

-

The participants agreed that it was interesting and timely to have a concurrency-related challenge. In general the feeling was that it is good to have modular challenges, which can be broken down into smaller subproblems. There was also a suggestion to have challenges in the form: given a verified program, extend it to...

- Tool vs. user :

-

An interesting aspect remains regarding what we are actually measuring: the tool or the user. To focus more on measuring the tool, the challenge descriptions could include an informal description of the necessary invariants. However, it was also remarked that this might restrict the variety of tools participating in the competition. Another possibility, to help focus the competition on the tools, would be to create mixed teams, where you use a tool that you do not know in advance (possibly with a tutor). As a result of this discussion, in the next edition of this competition, we plan to start the day with a Dafny tutorial, followed by an out-of-competition challenge, open to anybody interested in participating.

- Timing :

-

The program as it is now, is very dense. A slightly larger break between the challenges would be welcome. Since participants often continue working on their solutions after the competition, a post-competition deadline to submit solutions would also be welcomed. The possibility of providing all challenges to the competitors at the same time was discussed, such that participants can organise their own time to work on a challenge. In that case, to avoid two person teams having an advantage over single person teams, because they can distribute the work, all teams would be allowed the use of only one computer.

- Reporting :

-

There was much discussion about the possibility of publishing details from these competitions. There have been several competition report papers, and there has been a special issue of STTT on the VerifyThis competition in 2012. New publications need to provide new insights. One possibility is to encourage several participants to write a joint paper about one particular challenge, where they compare their different solutions. Another possibility is to reach an agreement with an editor to publish a series of competition reports, summarising the main facts of the competition. In general, the participants agreed that it is important to make the (polished) solutions publicly available for others to inspect and compare. The solutions of the best student team prize winners, the KIV team, are available at https://swt.informatik.uni-augsburg.de/swt/projects/verifythis-competition-2015/, while solutions of the best overall team prize winners, the Why3 team, are available at http://toccata.lri.fr/gallery/why3.en.html. For further solutions to competition challenges, we refer to http://etaps2015.verifythis.org/.

5.10 Final remarks

The VerifyThis 2015 challenges have offered a substantial degree of complexity and difficulty. A new development compared to earlier editions of the competition was the introduction of a concurrency-related challenge. Furthermore, we are happy to note that this year two teams participated using bounded verification tools (CBMC and mCRL2) to check functional properties. We hope such participation contributes to better understanding of the strengths of different kinds of tools and opens new avenues for combining them.

Two further insights demonstrated by the solutions this year were the importance of a good lemma library, and of a good specification language. The similarity between the specification language of mCRL2 and of “auto-active” verification systems was nothing but remarkable.

A new edition of the VerifyThis competition will be held as part of ETAPS 2016.

Notes

Primarily due to challenges being too complex for the available time slots.

SV-COMP is associated with TACAS.

Here, the judges would primarily like to cite the semantic collaboration technique demonstrated by the AutoProof team.

References

Ahrendt, W., Beckert, B., Bruns, D., Bubel, R., Gladisch, C., Grebing, S., Hähnle, R., Hentschel, M., Herda, M., Klebanov, V., Mostowski, W., Scheben, C., Schmitt, P.H., Ulbrich, M.: The KeY platform for verification and analysis of Java programs. In: Giannakopoulou, D., Kroening, D. (eds.) 6th international conference on verified software: theories, tools and experiments (VSTTE 2014), vol. 8471 of LNCS, pp. 55–71. Springer, Berlin (2014)

Bormer, T., Brockschmidt, M., Distefano, D., Ernst, G., Filliâtre, J.-C., Grigore, R., Huisman, M., Klebanov, V., Marché, C., Monahan, R., Mostowski, W., Polikarpova, N., Scheben, C., Schellhorn, G., Tofan, B., Tschannen, J., Ulbrich, M.: The COST IC0701 verification competition 2011. In: Beckert, B., Damiani, F., Gurov, D. (eds.) International conference on formal verification of object-oriented systems (FoVeOOS 2011), vol. 7421 of LNCS, pp. 3–21. Springer, Berlin (2011)

Beyer, D.: Software verification and verifiable witnesses—(report on SV-COMP 2015). In: Baier, C., Tinelli, C. (eds.) 21st international conference on tools and algorithms for the construction and analysis of systems (TACAS 2015), vol. 9035 of LNCS, pp. 401–416. Springer, Berlin (2015)

Blom, S., Huisman, M.: The VerCors tool for verification of concurrent programs. In: Jones C.B., Pihlajasaari, P., Sun, J. (eds.) 19th International symposium on formal methods (FM 2014), vol. 8442 of LNCS, pp. 127–131. Springer, Berlin (2014)

Cranen, S., Groote, J.F., Keiren, J.J.A., Stappers, F.P.M., de Vink, E.P., Wesselink, W., Willemse T.A.C.: An overview of the mCRL2 toolset and its recent advances. In: Piterman, N., Smolka, S.A. (eds.) 19th international conference on tools and algorithms for the construction and analysis of systems (TACAS 2013), vol. 7795 of LNCS, pp. 199–213. Springer, Berlin (2013)

Ernst, G., Pfähler, J., Schellhorn, G., Haneberg, D., Reif, W.: KIV: overview and verifyThis competition. Int. J. Softw. Tools Technol. Transf. 17(6), 677–694 (2015)

Filliâtre, J.-C., Paskevich, A.: Why3—where programs meet provers. In: Felleisen, M., Gardner, P. (eds.) 22nd European symposium on programming (ESOP 2013), vol. 7792 of LNCS, pp. 125–128. Springer, Berlin (2013)

Filliâtre, J.-C., Paskevich, A., Stump, A.: The 2nd verified software competition: experience report. In: Klebanov, V., Biere, A., Beckert, B., Sutcliffe, G. (eds.) 1st international workshop on comparative empirical evaluation of reasoning systems (COMPARE 2012), vol. 873 of CEUR workshop proceedings. CEUR-WS.org (2012)

Howar, F., Isberner, M., Merten, M., Steffen, B., Beyer, D., Păsăreanu, C.S.: Rigorous examination of reactive systems. Int. J. Softw. Tools Technol. Transf. 16(5), 457–464 (2014)

Huisman, M., Klebanov, V., Monahan, R.: On the organisation of program verification competitions. In: Klebanov, V., Beckert, B., Biere, A., Sutcliffe, G. (eds.) 1st international workshop on comparative empirical evaluation of reasoning systems (COMPARE 2012), vol. 873 of CEUR workshop proceedings. CEUR-WS.org (2012)

Huisman, M., Klebanov, V., Monahan, R.: Verifythis 2012. Int. J. Softw. Tools Technol. Transf. 17(6), 647–657 (2015)

Hitotumatu, H., Noshita, K.: A technique for implementing backtrack algorithms and its application. Inf. Process. Lett. 8(4), 174–175 (1979)

Klebanov, V., Beckert, B., Biere, A., Sutcliffe, G. (eds.). Proceedings of the 1st international workshop on comparative empirical evaluation of reasoning systems (COMPARE 2012), vol. 873 of CEUR workshop proceedings. CEUR-WS.org (2012)

Kirchner, F., Kosmatov, N., Prevosto, V., Signoles, J., Yakobowski, B.: Frama-C: a software analysis perspective. Formal Asp. Comput. 27(3), 573–609 (2015)

Klebanov, V., Müller, P., Shankar, N., Leavens, G.T., Wüstholz, V., Alkassar, E., Arthan, R., Bronish, D., Chapman, R., Cohen, E., Hillebrand, M., Jacobs, B., Leino, K.R.M., Monahan, R., Piessens, F., Polikarpova, N., Ridge, T. Smans, J., Tobies, S., Tuerk, T., Ulbrich, M., Weiß, B.: The 1st verified software competition: experience report. In: Butler, M., Schulte, W. (eds.) 17th international symposium on formal methods (FM 2011), vol. 6664 of LNCS, pp. 154–168. Springer, Berlin (2011)

Knuth, D.E.: Dancing links. arXiv:cs/0011047 (2000) (arXiv preprint)

Kobayashi, N., Sato, R., Unno, H.: Predicate abstraction and CEGAR for higher-order model checking. In: Hall, M.W., Padua, D.A. (eds.) 32nd ACM SIGPLAN conference on programming language design and implementation (PLDI 2011), pp. 222–233. ACM (2011)

Kroening, D., Tautschnig, M.: CBMC—C bounded model checker—(competition contribution). In: Ábrahám, E., Havelund, K. (eds.) 20th international conference on tools and algorithms for the construction and analysis of systems (TACAS 2014), vol. 8413 of LNCS, pp. 389–391. Springer, Berlin (2014)

Leino, K.R.M.: Dafny: an automatic program verifier for functional correctness. In: Clarke, E.M., Voronkov, A. (eds.) 16th international conference on logic for programming, artificial intelligence, and reasoning (LPAR 2010), vol. 6355 of LNCS, pp. 348–370. Springer, Berlin (2010)

Penninckx, W., Jacobs, B., Piessens, F.: Sound, modular and compositional verification of the input/output behavior of programs. In: Vitek, J. (ed.) 24th European symposium on programming (ESOP 2015), vol. 9032 of LNCS, pp. 158–182. Springer, Berlin (2015)

Polikarpova, N., Tschannen, J., Furia, C.A., Meyer, B.: Flexible invariants through semantic collaboration. In: Jones, C.B., Pihlajasaari, P., Sun, J. (eds.) 19th international symposium on formal methods (FM 2014), vol. 8442 of LNCS, pp. 514–530. Springer, Berlin (2014)

Swamy, N., Chen, J., Fournet, C., Strub, P.-Y., Bhargavan, K., Yang, J.: Secure distributed programming with value-dependent types. J. Funct. Program. 23(4), 402–451 (2013)

Sedjelma, S.M.: A parallel extended GCD algorithm. J. Discret. Algorithms 6(3), 526–538 (2008)

Tschannen, J., Furia, C.A., Nordio, M., Polikarpova, N.: AutoProof: auto-active functional verification of object-oriented programs. In: Baier, C., Tinelli, C. (eds.) 21st international conference on tools and algorithms for the construction and analysis of systems (TACAS 2015), vol. 9035 of LNCS, pp. 566–580. Springer, Berlin (2015)

Acknowledgments

The organisers would like to thank Wojciech Mostowski and Radu Grigore for their feedback and support prior to the competition. The organisers also thank the competition’s sponsors: Formal Methods Europe, Galois, Inc., and Microsoft Research. Their contributions helped us to support participants with travel grants, and to finance the various prizes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Huisman, M., Klebanov, V., Monahan, R. et al. VerifyThis 2015. Int J Softw Tools Technol Transfer 19, 763–771 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10009-016-0438-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10009-016-0438-x