Abstract

Purpose

In cases of highly atrophic alveolar ridges, augmentation procedures became a frequent procedure to gain optimal conditions for dental implants. Especially in the maxilla sinus floor elevation procedures represent the gold standard pre-prosthetic and mainly successful procedure. The perforation of the Schneiderian is one of the most common complications. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether the intraoperative perforation of the Schneiderian membrane has an impact on long-term implant success.

Methods

Thirty-four patients from a former study collective of the years 2005 and 2006 with a total of 41 perforations were invited for a follow-up examination to determine the long-term success rates after sinus floor elevation and subsequent implantation.

Results

Twenty-one patients with 25 perforations were subsequently re-evaluated. One implant was lost due to a of periimplant infection after 232 days, resulting in an implant survival rate of 98% within a mean follow-up period of 8.9 years (± 1.5 years).

Conclusion

Regarding the long-term success, there was no increased risk for implant failure or other persisting complications, e.g., sinusitis, after intraoperative perforation during sinus floor elevation in this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since first reported in the 1980s, the sinus lift procedure has become the gold standard procedure for augmentation of the atrophic maxilla [1, 2], which is, besides common complications (e.g., bleeding, swelling), a highly predictive and successful procedure [3,4,5].

The perforation of the Schneiderian membrane represents one of the more specific complications during sinus floor elevation [6,7,8,9], occurring in a considerably wide incidental range from 10% up to 44% in the present literature [8, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19], whereas most studies set the incidence of perforations at a 20–25% among all sinus lift operations [20,21,22].

In many cases of intraoperative perforations, difficult anatomic circumstances were found, which might have contributed to a damage of the Schneiderian membrane. In a systematic review performed by Pommer et al., septa were found in 28.4% of intraoperative perforations [23]. Other reasons were summarized in other pathologic conditions (e.g., scaring) or very thin and vulnerable membranes [3].

Up to now, studies concerning complications during sinus lift procedures are further on underrepresented and the impact on long-term success is still not very well known. The aim of this study was to re-evaluate a cohort of 41 intraoperative perforations [24] of the Schneiderian membrane in 34 patients and its consecutive long-term influence on osseointegration, implant survival rates, and patients’ rehabilitation after dental implantation.

Material and methods

Patient recruitment

The study was conducted in accordance with the WMA Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects and was approved by the local Ethics committee (AZ 132/10). All patients were meticulously informed and gave their written consent for participation.

Two hundred one sinus floor elevations were counted in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Schleswig-Holstein University Hospital of Kiel in the years between 2005 and 2006. In this collective of patients, the Schneiderian membrane was perforated during 41 procedures in 34 patients. For this retrospective evaluation, patient records were recollected and further assessed regarding implant insertions, implant failure, and further complications.

Surgical procedure

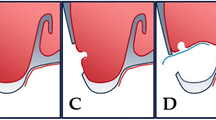

Sinus elevation procedures were external sinus floor elevations through a bone window in the facial sinus wall in our study cohort. Augmentation of the sinus floor was performed with bone substitute material and bone filter material in defects less than 2 cm3, whereas above 2 cm3, whether mandible bone from the oblique ridge or iliac crest was harvested to augment the sinus floor in combination with bone substitute material. Dependent on size of the Schneiderian membrane perforation and in order to prevent sinusitis due to displaced graft material, membranes were whether sutured (Vicryl 6.0, Ethicon, Norderstedt, Germany) and covered with a resorbable membrane (BioGide, Geistlich, Wolhusen, Switzerland) in defects beyond of 5 mm in diameter. Smaller perforations were solely covered with a collagen membrane, fibrin glue, or left without any treatment. Sutures were removed 7 to 10 days after surgery. Due to the estimated primary stability, dental implants were inserted simultaneously or following a delayed implantation protocol.

Medical record assessment

After implant insertion, yearly follow-up examinations were performed according to standardized protocols and panoramic radiographs were made 6 months after sinus floor elevation. Here, 21 patients regularly joined the routinely follow-up visits.

Patient records were screened for systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus), a previously diagnosed periodontitis or nicotine abuse.

Implant type, length and diameter were noted. Prosthodontic rehabilitation was distinguished in removable dentures and fixed bridgework. Origin of grafting material was further recorded. Simultaneously performed vertical augmentation was further noted as well as the position of the inserted implant. Implant success was defined as a prosthodontically integrated implant.

Statistical assessment

Statistical data analyses was performed applying GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated and implant survival was displayed in a Kaplan-Meier plot. If the probability of error was less than 5%, the result was presented as statistically significant.

Results

Among the 34 patients (24 female, 10 male) with 41 perforations of the Schneiderian membrane, a total of 25 perforations in 21 patients (13 female, 8 male) could be included in this retrospective long-term evaluation. Mean age of the patients was 63.8 years (SD 14.7 years) in the study cohort. The mean follow-up period in this study was 8.9 years (SD 1.5 years). Among the study groups, a total of 3 patients had diabetes type II (14.3%). Periodontitis was previously diagnosed in 13 patients (61.9%) and 13 patients were smokers (61.9%).

Perforation of the Schneiderian membrane was covered with a collagen membrane in 14 procedures (56%) and in 5 patients (20%), a suture was combined with a membrane. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of perforation management. In the study group, a total 49 implants were inserted, whereas 20 implants were inserted simultaneously to sinus floor augmentation and 29 implants in a second procedure (59.2%). Twenty-five implants inserted in the premolar region and 24 implants inserted in the molar region (Table 1).

Material for augmentation was mainly a mixture of intraorally harvested bone with bone replacement material in 16 procedures (64%) followed by a mixture of iliac crest and bone replacement material in 5 sinus lifting procedures (20%) (Fig. 2). One patient was treated with bone replacement material alone (4%) and 3 patients received an autologous bone graft originating from the mandible (14.3%). In 23.8% of cases (5 patients), an additional onlay grafting procedure was performed.

Six different implant types were used. Technical data and implant manufacturers are displayed in Tables 2 and 3. Twelve implants served prosthodontically in removable dentures (24.5%), whereas the remaining 37 implants were crowns and bridgework.

Regarding short-term complication, one patient developed a dehiscence of the gingival wound leading to a delayed wound healing without any dissemination of infection. Another patient struggled with signs of sinusitis as previously reported [24]. The long-term evaluation revealed that among the 49 inserted implants, one was lost due to a periimplant infection after 232 days leading to an implant survival of 98% in Kaplan-Meier analysis (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The aim of this re-evaluation of intraoperative perforations of the Schneiderian membrane in a cohort of previously reported 34 patients was to determine its long-term influence on the implants’ osseointegration, the survival rates, and patients’ rehabilitation after dental implantation [24]. Twenty-one patients with 24 perforations could be included in this approximately 9-year follow-up.

Perforating the Schneiderian membrane during sinus lifting procedure is mostly common and of vary between 10 and 44% [8, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

Alongside with the surgical experience of the surgeon, scared tissue due to previously performed surgery or infection may increase the risk to perforate the Schneiderian membrane [15, 25,26,27]. Variations of the anatomy including the shape of the lateral maxillary sinus wall, sinus septa, and the thickness of the membrane itself may represent further influcence factors for intraoperative perforations [15, 23, 25,26,27]. In our former study, collective thin membranes were observed in 27% of patients. Sinus septa were seen in 22% of the patients [24]. Other studies suggested that sinus floor elevation might be relatively contraindicated in anatomical variations like septa or mucosal swelling [16].

In the present study, one implant was removed due to early onset of periimplantitis in the first year after implantation. The resulting implant survival of 98% in our study after 8.9 years is in the comparable upper range of currently published studies with survival rates of 88 to 100% 10–14 years after dental implant insertion [28,29,30,31,32,33]. Another study evaluating the implant success over a 1-year period and the influence of the bone grafts’ origin on the complication rate did not reveal any significance regarding the occurrence of postoperative complications. Furthermore, no implant was lost during the observation period [19] and another study also did not reveal any connection between complications and membrane perforation during the observation period of 8 years [25]. In contrast to these studies, Nolan et al. reported about a statistically significant higher use of antibiotic treatment of sinus infections and higher rates of graft failure in 359 sinus floor elevation procedures with a reported perforation rate of 48.8% (Nolan et al. 2014).

The occurrence of complications might also be dependent on the surgical management in case of a due to the efficiency of perforation’s closure. So far, there are no existing guidelines to standardize perforation closure on an evidence-based level. The published studies suggest covering small perforations with collagen or demineralized laminar bone membranes or fibrin glue and an additional resorbable suture of larger perforations in order to close the dehiscence completely [8, 16, 22]. Other studies covered even larger perforations with membranes only and did not report of severe adverse events with clinical relevance [19, 21, 22, 34]. In our study, a perforation was not associated with a reduced implant success, but was in contrary found to result in a reduced implant survival rate in a study performed by Proussaefs et al. in 2004, when a perforation exceeded 2 mm. In another study, the implant survival rates after membrane reconstruction were found to inversely correlate with the size of the perforations [35].

In all these cases, a lateral approach is necessary in order to recognize and subsequently manage the perforation. In original cohort of the study, four procedures were terminated because of the extent of the perforation in two cases, vulnerable mucosa and a retention cyst in one case each. The procedure was performed again after 6 months without further complication [24]. This in accordance with other studies reporting disrupting surgery when the size of perforations are too extensive to repair [10, 20].

Besides the mode of membrane repair, the timing of implant placement might also influence the overall implant survival after membrane perforations. In our study, immediate implant was only placed immediately when a high primary stability could be ensured due to a good residual bone quality, which was in accordance with another study as well [36]. However, it was suggested that patients with a residual bone height between 1 and 3 mm were at risk for implant failures in a one-stage surgery with a lateral approach in sinus floor elevation [26]. In all other cases, the implants were inserted in a two-stage approach although the risk of complications might be increased. A previously published study, regardless of perforations, found that there was a significantly higher risk to develop a soft-tissue complication in the periimplant region due to a second procedure. Bone grafting was slightly not correlated with these complications but might implicate a potential influence as well [37].

In this context, other risk factors for implant success have to be considered, too. For example, the use of tobacco was found to have a negative impact on implant success after sinus floor elevation [38], when a total of 60 patients with 228 inserted implants were evaluated. Among smoking patients, implants success revealed 65.3% and therefore significantly lower compared to non-smokers with a success rate of 82.7%. Although some studies did not reveal a significant connection between the use of tobacco and implant survival [39, 40], it is widely accepted that smoking might represent a risk factor for wound healing disturbances and implant failure in several other studies [28, 41].

Conclusion

Our results indicate that the perforation of the Schneiderian membrane had no long-term impact on implant success rates or persisting long-term complications if the surgical management allows to cover the perforation or to change the surgical protocol to a two-stage surgery.

References

Boyne PJ, James RA (1980) Grafting of the maxillary sinus floor with autogenous marrow and bone. J Oral Surg 38(8):613–616

Tatum H Jr (1986) Maxillary and sinus implant reconstructions. Dent Clin N Am 30(2):207–229

Pikos MA (1999) Maxillary sinus membrane repair: report of a technique for large perforations. Implant Dent 8(1):29–34

Wiltfang J, Schultze-Mosgau S, Nkenke E, Thorwarth M, Neukam FW, Schlegel KA (2005) Onlay augmentation versus sinuslift procedure in the treatment of the severely resorbed maxilla: a 5-year comparative longitudinal study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 34(8):885–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2005.04.026

Boffano P, Forouzanfar T (2014) Current concepts on complications associated with sinus augmentation procedures. J Craniofac Surg 25(2):e210–e212. https://doi.org/10.1097/scs.0000000000000438

Ardekian L, Oved-Peleg E, Mactei EE, Peled M (2006) The clinical significance of sinus membrane perforation during augmentation of the maxillary sinus. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 64(2):277–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2005.10.031

Raghoebar GM, Timmenga NM, Reintsema H, Stegenga B, Vissink A (2001) Maxillary bone grafting for insertion of endosseous implants: results after 12-124 months. Clin Oral Implants Res 12(3):279–286

Schwartz-Arad D, Herzberg R, Dolev E (2004) The prevalence of surgical complications of the sinus graft procedure and their impact on implant survival. J Periodontol 75(4):511–516. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2004.75.4.511

Proussaefs P, Lozada J, Kim J, Rohrer MD (2004) Repair of the perforated sinus membrane with a resorbable collagen membrane: a human study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 19(3):413–420

Timmenga NM, Raghoebar GM, Boering G, van Weissenbruch R (1997) Maxillary sinus function after sinus lifts for the insertion of dental implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 55(9):936–939 discussion 940

Wiltfang J, Schultze-Mosgau S, Merten HA, Kessler P, Ludwig A, Engelke W (2000) Endoscopic and ultrasonographic evaluation of the maxillary sinus after combined sinus floor augmentation and implant insertion. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 89(3):288–291

Barone A, Santini S, Sbordone L, Crespi R, Covani U (2006) A clinical study of the outcomes and complications associated with maxillary sinus augmentation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 21(1):81–85

Silva FM, Cortez AL, Moreira RW, Mazzonetto R (2006) Complications of intraoral donor site for bone grafting prior to implant placement. Implant Dent 15(4):420–426. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.id.0000246225.51298.67

Timmenga NM, Raghoebar GM, Liem RS, van Weissenbruch R, Manson WL, Vissink A (2003) Effects of maxillary sinus floor elevation surgery on maxillary sinus physiology. Eur J Oral Sci 111(3):189–197

Pikos MA (2008) Maxillary sinus membrane repair: update on technique for large and complete perforations. Implant Dent 17(1):24–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/ID.0b013e318166d934

van den Bergh JP, ten Bruggenkate CM, Disch FJ, Tuinzing DB (2000) Anatomical aspects of sinus floor elevations. Clin Oral Implants Res 11(3):256–265

Shlomi B, Horowitz I, Kahn A, Dobriyan A, Chaushu G (2004) The effect of sinus membrane perforation and repair with Lambone on the outcome of maxillary sinus floor augmentation: a radiographic assessment. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 19(4):559–562

Nolan PJ, Freeman K, Kraut RA (2014) Correlation between Schneiderian membrane perforation and sinus lift graft outcome: a retrospective evaluation of 359 augmented sinus. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 72(1):47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2013.07.020

Sakkas A, Konstantinidis I, Winter K, Schramm A, Wilde F (2016) Effect of Schneiderian membrane perforation on sinus lift graft outcome using two different donor sites: a retrospective study of 105 maxillary sinus elevation procedures. GMS Interdiscip Plast Reconstr Surg DGPW 5:Doc11. https://doi.org/10.3205/iprs000090

Khoury F (1999) Augmentation of the sinus floor with mandibular bone block and simultaneous implantation: a 6-year clinical investigation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 14(4):557–564

Wannfors K, Johansson B, Hallman M, Strandkvist T (2000) A prospective randomized study of 1- and 2-stage sinus inlay bone grafts: 1-year follow-up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 15(5):625–632

van den Bergh JP, ten Bruggenkate CM, Krekeler G, Tuinzing DB (2000) Maxillary sinusfloor elevation and grafting with human demineralized freeze dried bone. Clin Oral Implants Res 11(5):487–493

Pommer B, Ulm C, Lorenzoni M, Palmer R, Watzek G, Zechner W (2012) Prevalence, location and morphology of maxillary sinus septa: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol 39(8):769–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01897.x

Becker ST, Terheyden H, Steinriede A, Behrens E, Springer I, Wiltfang J (2008) Prospective observation of 41 perforations of the Schneiderian membrane during sinus floor elevation. Clin Oral Implants Res 19(12):1285–1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01612.x

Moreno Vazquez JC, Gonzalez de Rivera AS, Gil HS, Mifsut RS (2014) Complication rate in 200 consecutive sinus lift procedures: guidelines for prevention and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 72(5):892–901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2013.11.023

Felice P, Pistilli R, Piattelli M, Soardi E, Barausse C, Esposito M (2014) 1-stage versus 2-stage lateral sinus lift procedures: 1-year post-loading results of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Eur J Oral Implantol 7(1):65–75

Johansson LA, Isaksson S, Lindh C, Becktor JP, Sennerby L (2010) Maxillary sinus floor augmentation and simultaneous implant placement using locally harvested autogenous bone chips and bone debris: a prospective clinical study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 68(4):837–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.093

Becker ST, Beck-Broichsitter BE, Rossmann CM, Behrens E, Jochens A, Wiltfang J (2015) Long-term survival of Straumann dental implants with TPS surfaces: a retrospective study with a follow-up of 12 to 23 years. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/cid.12334

Ostman PO, Hellman M, Sennerby L (2012) Ten years later. Results from a prospective single-centre clinical study on 121 oxidized (TiUnite) Branemark implants in 46 patients. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 14(6):852–860. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1708-8208.2012.00453.x

Fischer K, Stenberg T (2012) Prospective 10-year cohort study based on a randomized controlled trial (RCT) on implant-supported full-arch maxillary prostheses. Part 1: sandblasted and acid-etched implants and mucosal tissue. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 14(6):808–815. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1708-8208.2011.00389.x

Buser D, Janner SF, Wittneben JG, Bragger U, Ramseier CA, Salvi GE (2012) 10-year survival and success rates of 511 titanium implants with a sandblasted and acid-etched surface: a retrospective study in 303 partially edentulous patients. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 14(6):839–851. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1708-8208.2012.00456.x

Wittneben JG, Buser D, Salvi GE, Burgin W, Hicklin S, Bragger U (2014) Complication and failure rates with implant-supported fixed dental prostheses and single crowns: a 10-year retrospective study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 16(3):356–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/cid.12066

Vroom MG, Sipos P, de Lange GL, Grundemann LJ, Timmerman MF, Loos BG, van der Velden U (2009) Effect of surface topography of screw-shaped titanium implants in humans on clinical and radiographic parameters: a 12-year prospective study. Clin Oral Implants Res 20(11):1231–1239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01768.x

Aimetti M, Romagnoli R, Ricci G, Massei G (2001) Maxillary sinus elevation: the effect of macrolacerations and microlacerations of the sinus membrane as determined by endoscopy. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 21(6):581–589

Hernandez-Alfaro F, Torradeflot MM, Marti C (2008) Prevalence and management of Schneiderian membrane perforations during sinus-lift procedures. Clin Oral Implants Res 19(1):91–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01372.x

Cha HS, Kim A, Nowzari H, Chang HS, Ahn KM (2012) Simultaneous sinus lift and implant installation: prospective study of consecutive two hundred seventeen sinus lift and four hundred sixty-two implants. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/cid.12012

Esquivel-Upshaw J, Mehler A, Clark A, Neal D, Gonzaga L, Anusavice K (2015) Peri-implant complications for posterior endosteal implants. Clin Oral Implants Res 26(12):1390–1396. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.12484

Kan JY, Rungcharassaeng K, Lozada JL, Goodacre CJ (1999) Effects of smoking on implant success in grafted maxillary sinuses. J Prosthet Dent 82(3):307–311

Blomqvist JE, Alberius P, Isaksson S (1996) Retrospective analysis of one-stage maxillary sinus augmentation with endosseous implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 11(4):512–521

Chambrone L, Preshaw PM, Ferreira JD, Rodrigues JA, Cassoni A, Shibli JA (2013) Effects of tobacco smoking on the survival rate of dental implants placed in areas of maxillary sinus floor augmentation: a systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.12186

Anner R, Grossmann Y, Anner Y, Levin L (2010) Smoking, diabetes mellitus, periodontitis, and supportive periodontal treatment as factors associated with dental implant survival: a long-term retrospective evaluation of patients followed for up to 10 years. Implant Dent 19(1):57–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/ID.0b013e3181bb8f6c

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors state that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The local Ethics Committee University of Kiel approved this study (AZ 132/10). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beck-Broichsitter, B.E., Gerle, M., Wiltfang, J. et al. Perforation of the Schneiderian membrane during sinus floor elevation: a risk factor for long-term success of dental implants?. Oral Maxillofac Surg 24, 151–156 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-020-00829-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-020-00829-8