Abstract

Mental illnesses are the leading cause of disease burden among children and young people (CYP) globally. Low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) are disproportionately affected. Enhancing mental health literacy (MHL) is one way to combat low levels of help-seeking and effective treatment receipt. We aimed to synthesis evidence about knowledge, beliefs and attitudes of CYP in LMICs about mental illnesses, their treatments and outcomes, evaluating factors that can enhance or impede help-seeking to inform context-specific and developmentally appropriate understandings of MHL. Eight bibliographic databases were searched from inception to July 2020: PsycInfo, EMBASE, Medline (OVID), Scopus, ASSIA (ProQuest), SSCI, SCI (Web of Science) CINAHL PLUS, Social Sciences full text (EBSCO). 58 papers (41 quantitative, 13 qualitative, 4 mixed methods) representing 52 separate studies comprising 36,429 participants with a mean age of 15.3 [10.4–17.4], were appraised and synthesized using narrative synthesis methods. Low levels of recognition and knowledge about mental health problems and illnesses, pervasive levels of stigma and low confidence in professional healthcare services, even when considered a valid treatment option were dominant themes. CYP cited the value of traditional healers and social networks for seeking help. Several important areas were under-researched including the link between specific stigma types and active help-seeking and research is needed to understand more fully the interplay between knowledge, beliefs and attitudes across varied cultural settings. Greater exploration of social networks and the value of collaboration with traditional healers is consistent with promising, yet understudied, areas of community-based MHL interventions combining education and social contact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental illnesses are the leading cause of disease burden among children and young people (CYP) globally [1] and low-and middle-income countries (LMIC) are disproportionately affected. LMIC populations are predominantly young [2] and are vulnerable to developing mental disorders [3]. Half of all lifetime mental illnesses begin by adolescence which portends markedly worse outcomes than onset later in life [4, 5]. The Lancet Commission on child health and wellbeing identifies that mental health problems are becoming dominant among CYP and substantial investment in prevention approaches is required [6]. There are considerably lower rates of recognition and treatment of mental illness in LMICs [7]. Evidence reports the gap between those needing treatment and those receiving it is up to 90% [8]. Structural barriers including inadequate funding, lack of resources and trained personnel, sub-optimal infrastructure and poorly integrated health systems all contribute to inaccessible mental health care [9]. In LMICs, fewer people seek professional help compared to in high-income settings and where they do, there are long delays with variable pathways [10].

Enhancing mental health literacy (MHL) is one way to combat excessively high rates of undertreatment of mental illnesses among CYP. However, understanding current knowledge and attitudes towards mental illnesses is an important first step towards developing an evidence base and interventions to improve literacy. MHL refers to the “knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management or prevention” [11] and comprises several, interlinked components that include: (a) the ability to recognise specific disorders or different types of psychological distress; (b) knowledge and beliefs about risk factors and causes; (c) knowledge and beliefs about self-help interventions; (d) knowledge and beliefs about professional help available; (e) factors and attitudes which facilitate recognition and appropriate help-seeking; and (f) knowledge of how to seek mental health information. MHL proponents reason that obtaining adequate knowledge of how and when disorders develop and appraising the need for help increases help-seeking behaviours boosting the chance of receiving appropriate and effective treatment [12, 13]. In LMICs, targeting MHL is a specific recommendation for improving the health and wellbeing of younger populations [14]. Evidence from two separate systematic reviews shows that perceived lack of knowledge about mental health problems is one of the most prominent barriers to intended help-seeking reported from the perspective of young people [15, 16]. Research also shows that negative attitudes about mental illness and treatment deters people from seeking help [17].

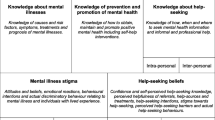

To promote conceptual clarity, we view MHL as a theory that contains multiple constructs for the present review [18]. This allows clearer formulation of hypothesised relationships, better articulation and understanding of the interrelationships between constructs and outcomes of interest and the development of testable theories regarding the extent that MHL influences mental health behaviours. For the purposes of this review, we define MHL as knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about mental disorders which aids recognition, management or prevention incorporating recognition of developing disorders and effective help-seeking strategies [12]. Jorm’s theory encapsulates knowledge of professional help-seeking, self-treatment and how to seek information to effectively support individual’s to seek appropriate and effective treatments for themselves and to assist others [12] which may have additional relevance in LMIC settings which are broadly defined as collectivist cultures where families and communities take a prominent role in decision-making about health [19]. Help-seeking has particular salience for enhancing capacity in the demand for services and supporting efforts to contribute to closing the significant treatment gap in LMICs [6]. We have expressly included attitudes and beliefs that promote recognition, incorporating stigma, as there is inconsistent evidence of the interrelationship between mental health knowledge and stigma [20,21,22]. Current evidence from a meta-analysis demonstrates that stigmatising attitudes towards people with mental illness significantly predicts actively seeking treatment for mental health problems [23] and as such is a significant barrier to accessing adequate treatment.

Existing synthesised evidence of MHL in children and young people in LMICs is lacking. Two reviews examine adolescent help-seeking and the relationship with MHL [15, 16]; however, these are not specific to LMICs and less than 8% of included studies originated in LMICs. A single review helpfully examines the conceptualisation of MHL in adolescent populations [14] but again is largely focused on evidence from high-income settings and of the 91 studies included just 6 were conducted in low-resource settings. To ensure context-specific and developmentally appropriate MHL constructs are available, we aim to synthesise evidence about the knowledge, beliefs and attitudes of CYP in LMICs about mental illnesses, their treatments and outcomes, evaluating factors that can enhance or impede help-seeking.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We sought to identify studies reporting primary evidence regarding MHL; thus, we included research that examined perceptions, views and attitudes about mental illnesses and treatment. Studies exploring disorder recognition, knowledge about causes, help-seeking and self-help including factors influencing these MHL components were eligible for inclusion. Participant groups were included if they were under 18 years of age and where this was not clear, we included studies with population group mean age under 18. LMICs were defined by Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) between 2018 and 2020.Footnote 1

We included peer reviewed journal articles and dissertations which reported primary data. There were no restrictions on study type or the date the study was completed. Conference paper authors were contacted by email to request published reports of conference proceedings. These were excluded if complete information could not be provided by researchers. All languages were included. Data from non-English papers were screened and extracted in different languages by bilingual researchers affiliated with and supported by the study team. Six non-English papers were reviewed at title and abstract screening (Chinese, Portuguese, Spanish, Serbian). Two were excluded at full-text review (Chinese) which resulted in 4 non-English papers (Portuguese, Serbian, Spanish). Inclusion/exclusion criteria are described in Additional File 1.

Search strategy

Eight bibliographic databases were searched from inception to July 2020: PsycInfo, EMBASE, Medline (OVID), Scopus, ASSIA (ProQuest), SSCI, SCI (Web of Science) CINAHL PLUS, Social Sciences full text (EBSCO). Test searches were completed between October 2018 and January 2019 iteratively readjusting and refining the search strategy. Initial searches were conducted in January 2019 and updated in July 2020. The search strategy incorporated four key areas comprising respondent views and attitudes, mental health, mental illnesses and emotional well-being, children and young people and originating from LMIC. Searches terms included ‘mental illness’, ‘low- and middle-income countries’, ‘perception’, ‘child’ and ‘adolescent’ using synonyms, truncations, and wildcards. An example search strategy is available in Additional File 2. Forward citation tracking was utilised for included papers from January 2019 until April 2020 in both Web of Science and Scopus [24]. The methods and results are reported consistent with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [25]. This review has been registered in PROSPERO (CRD42019122057). A sample search is described in Additional File 2.

Data extraction and appraisal

Included studies were independently screened with each title and abstract screened by two separate researchers from the study team. Full-text review was subsequently conducted by two independent reviewers within the study team. Conflicts were assessed by two members of the study team who were not involved in the original decision (LR and HB) until consensus was reached. Approximately 95% concordance was reached between reviewers at full-text review.

Data were extracted to an Excel sheet developed purposely and piloted prior to review. Qualitative and quantitative outcome data were extracted simultaneously including year of publication, country, and setting (community, school-based, clinical), study design, primary aim, MHL definition and use of scale, inclusion/exclusion and analysis. Extraction allowed for both deductive coding to existing mental health literacy components and inductive coding to allow for the inclusion of data that fell out with the MHL framework [11]. Quality appraisal comprised the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [26] designed to appraise five classes of research in mixed studies systematic reviews. Articles were not excluded based on quality assessment as empirical evidence is lacking to support exclusion based on quality criteria [27, 28]. Scores were expressed as a percentage of possible items divided by affirmative items. Each study was then classified as weak (≤ 50%), moderate–weak (51–65%), moderate–strong (66–79%), or strong (≥ 80%) based on a methodological scoring system [29].

Data analysis and synthesis

A narrative synthesis of qualitative and quantitative studies was conducted because of marked methodological and clinical heterogeneity between studies [30]. Using deductive and inductive thematic methods within an existing conceptual framework [11], the synthesis involved four stages [30]. See Fig. 1 for details of the synthesis process. To evaluate the robustness of our synthesis, we examined the findings within the analysis contained in each of our MHL conceptualisations when a) studies with weak quality scores were removed and b) studies with moderate–weak scores were removed. We then assessed the contribution of each individual piece of evidence to the consistency of descriptions within our synthesis to examine whether different pieces of information were compatible with the overall synthesis. Given the volume of evidence in included manuscripts, we presented the dominant themes and higher-order categories in our synthesis.

Results

Study characteristics

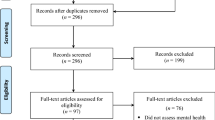

A PRISMA study flow diagram in Fig. 2 describes how papers were selected for inclusion. 58 papers (41 quantitative, 13 qualitative and 4 mixed methods) representing 52 separate studies were appraised in this review. 36,429 participants with a mean age of 15.3 [10.4–17.4] were included. No study included child populations alone, i.e., up to age 10. With the exception of six papers [31,32,33,34,35,36], all studies drew their samples from school-going populations.

Studies from upper middle- (n = 28) and lower middle-income countries (n = 26), as per OECD classification, dominated, with a dearth of published research from the least developed nations (n = 2). Across studies, 26 separate LMICs were represented including one study from each Turkey, Iran, Colombia, Sri Lanka, Egypt, Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Uganda, Ghana and Zambia, two studies from each South Africa, Serbia and Pakistan and three from each Vietnam, Jordan (3 same study), Kenya, Malaysia and Brazil. Countries most represented included China (n = 6), India (n = 4), Nigeria (n = 6; 3 same study) and Jamaica (n = 5; 3 same study). Four studies conducted internationally compared MHL between high-income and low-income settings [37,38,39,40] and one compared MHL between two LMICs [41]. The remainder of included papers were single country studies (Table 1).

Quality appraisal

The quality of studies ranged from 0 (no criteria met) to 100% (all criteria met) on the MMAT. The majority of qualitative studies achieved scores of 100% while fewer studies utilising other designs achieved high scores on quality. Overall, randomised trials and quasi-experimental designs were of poorer quality. Studies employing descriptive quantitative designs were predominantly moderate quality. Variation in quality was evident; risk of selection and measurement bias were identified in many studies, specifically in use of instruments not validated for target populations. Quality appraisals are detailed in Table 2.

MHL components

Ability to recognise mental illnesses

Evidence of CYP ability to recognize mental illnesses in others was primarily derived from surveying convenience samples of school-going CYP and responses were varied [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. Less than half of populations examined responded correctly to questions about common signs and symptoms, risk factors and aetiology, effectiveness of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments and the prognosis of mental illnesses including outcomes. Proportions of adolescent samples (range n = 354–1999) accurately endorsing indicative features of mental illnesses ranged from 1.5 to 49.9% [43,44,45]. Mean scores of depression literacy in separate samples assessed at different times but drawn from similar populations in Malaysia (range n = 101–202) varied from 5.01 to 12.67 on a 21 point scale [48, 49]. Vietnamese adolescents (n = 1075) had mean scores on general mental health literacy ranging from 2.49 to 2.67 (5 point subscales) on assessments of recognition, knowledge of risk factors and self-treatment [51].

Vignette methodologies used in large populations (range n = 285–1999) found that 83.6% of secondary school students in Sri Lanka accurately detected depression compared to 82.2% in India, 50% in Iran and 4.8% in Nigeria [42, 43, 45, 46]. Just one study evaluated CYP knowledge of other diagnoses (psychosis and social phobia) and demonstrated identification accuracy of 68.7% and 62.1% respectively [45]. Young people in included studies who displayed symptoms of mental illness, most commonly depression, but were undiagnosed and untreated, demonstrated limited ability to recognize their own mental illness [52,53,54]. However, evidence was obtained from moderately weak methods employed in quantitative designs. Between 8.3 and 50% of those with clinically significant symptoms in nationally representative cohorts (range 1754–2349) recognized having a problem that would warrant treatment [52, 53].

Eliciting words or phrases attributed to someone with mental illness, with the purpose of evaluating knowledge and by default, misconceptions about mental illness, was used in a minority of qualitative and quantitative studies. These studies highlighted CYP beliefs about the manifestation of mental illness in the form of visual or behavioural indicators which could be observed externally [40, 55, 56]. Five studies included evidenced that young people (range n = 19–1168) also attributed a range of typical symptoms to mental illnesses [33, 57,58,59,60]. Symptoms included sad mood, anxiety, apathy, social withdrawal, insomnia, decreased ability to think and lack of appetite. Despite this, many used derogatory terms to describe mental illnesses and held several stigmatizing views [39,40,41, 55]. Several of these textual descriptive analyses of the content of stigmatizing terms were derived from lower quality studies; however, there was further stronger evidence of pervasive stigmatised views (see section below).

Robust quantitative data from samples optimized for representativeness and measuring the relationship between age and MHL, evidenced that older participants and those with more education years tended towards better recognition than younger participants [46, 48, 53]. Females also tended towards improved recognition, though few studies examined sex differences [42, 46]. Social factors were also significant and higher socio-economic status and better recognition were linked in two studies [45, 53]. Similarly, geographic region may be important. Comparisons between countries regarding knowledge and treatments found no differences in literacy levels between high and lower income settings [37, 39, 57]. However, preliminary quantitative and qualitative data from exploratory analyses indicate within country differences may exist such that familiarity with psychiatric terminology and recognition of mental illnesses, is better in urban settings than rural [47, 56]. The quality of included studies was uneven, stronger evidence supported assertions that disorder recognition varied between settings and was mainly limited to depression. Weaker evidence was found that recognition and knowledge varied temporally, no studies assessed recognition longitudinally.

Knowledge of causes or risk factors for mental health problems

Quantitative, survey data across Vietnam, Jordan, Iran, India, Papua New Guinea, Nigeria and China illustrate specific misconceptions about the origins of mental illnesses alongside beliefs that mental illnesses are biopsychosocial in nature [38, 39, 44, 46, 47, 61]. Evidence indicates beliefs that mental illnesses are caused by weaknesses of character among 25–50% of convenience and representative samples [44, 59, 61]. Immoral behaviour was prominent among adolescent beliefs though perceptions of what constitutes immorality are, to an extent, socially and culturally determined [47]. Specific misdeeds varied between studies, e.g. familial jealousy, envy, adultery, theft, polygamy and interpersonal conflict were viewed as immoral in separate studies [47, 54, 59].

Religious, spiritual and supernatural explanations for mental illnesses were also pervasive within included studies. The majority of research examined the proportions of accurate causal attributions among possible answers in adolescent populations obtained using both purposive or probability sampling. Evidence was moderately strong that punishment for sin or test from God was considered causative, reported in between 10 and 35% of cross-sectional analyses [34, 44, 46, 54, 61]. There was also a perception that mental illness could be caused by a lack of faith or religion in qualitative analyses [54, 56]. Supernatural explanations for illnesses were endorsed by between 38 and 64% of adolescents in included studies [47, 50, 61]. Witchcraft, wizardry, evil spirits and sorcery were prominent interpretations [34, 39, 46, 50, 62] though the quality of included studies was mixed and older analyses may not represent present-day causal beliefs.

Confusion between physical and mental illnesses was highlighted in one study, particularly among younger participants [63], again evidence was not current and considered weak. However, there were repeated findings from quantitative designs that attributing mental illness to physical aetiology was prominent [33, 34, 46, 47, 55, 59, 63] and generally, evidence strongly supported varied physical explanations. Responses obtained to open questions in cross-sectional surveys about what causes mental illness or what it could reveal showed adolescents believed that fever, hypertension, malnutrition, head trauma, and stomach aches and pains, cerebral palsy, epilepsy and HIV variously contributed to mental illnesses [33, 46, 47, 55, 59]. Two studies provided evidence that adolescents believed mental illnesses were contagious [34, 63].

Normalising beliefs and evidence of wider illness conceptualisations were prominent in some CYP cohorts. Substantial proportions (between 60 and 72%) of large, diverse, adolescent cohorts in China, Iran, and India (range n = 354–1954) believe social factors and stressful life events are causative [38, 44, 46]. While a range of familial and societal stressors including family illness, abuse, trauma, bereavement, discrimination and poverty were identified, a strong theme emerged in both qualitative and quantitative data that upbringing and poor parenting are considered to cause mental illnesses [33, 38, 46, 61, 64]. Qualitative inquiry expounded this theme illuminating perceived causal factors including protective and autocratic parenting, lack of family communication and support, family history of mental illness, parental conflicts and poor family socio-economic situation [54], parental pressure to perform in academia [56] and lack of warmth and intimacy in familial relationships [65]. Beliefs that mental illnesses are biological or genetic in nature were identifiable in three quantitative studies [44, 46, 61]. These causes were reported by proportionately less CYP compared to other factors attributed to the onset of mental illness (10–33%).

Knowledge and beliefs about self-help interventions

Evidence of self-help strategies to enhance wellbeing [32, 56, 65,66,67] and manage mental health problems [68,69,70] is derived mainly from qualitative studies investigating CYP perspectives. Proactive and protective strategies identified from these studies included cognitive processing of stressful events [58], positive thinking [32] having good manners and behaving well [66], and community participation [56]. Stress avoidance was recognised as an important strategy as well as focusing on behaviours that enhance self-esteem and empowerment [67] and obtaining practical advice from others [68]. Cross-sectional analyses of quantitative data described self-help strategies CYP believed helpful for preventing depression [44, 46]. Beneficial practices endorsed by more than half of samples include meditation, relaxation training, using self-help books, increased physical activity, avoiding illicit and mood-altering substances, and taking vitamins. Interestingly, among both samples taking vitamins was considered more beneficial than taking antidepressants (54% vs 27–30%) [44, 46].

Exploratory qualitative analyses among Mexican and Brazilian CYP found a preference for dealing with problems alone, for example, seeking solace in their own rooms was considered important for processing difficult emotions like sadness, anger and stress [32, 65, 69]. Where CYP did express a preference in eliciting help from others, important sources generated from qualitative analyses included parents [32, 58, 66, 71] mothers in particular [32, 66], family members [32, 42, 61, 71, 72], peers [32, 58, 66, 71], siblings [43, 58, 71] teachers [58], church leaders [70], and neighbours/community members [32]. Two of these studies were appraised as weaker evidentiary sources [65, 71].

Members of immediate social networks were often the preferred option for advice and counsel about personal concerns from both quantitative and qualitative analyses [51, 54, 56, 71]. CYP in included studies appeared to purposely select certain social ties in response to specific problems [58, 73]. Selection also differed between genders; males were more likely to seek support from teachers, family members and friends compared to females [46]. Evidence is mixed regarding whether males or females are more likely to access school counsellors but counsellor gender may be an important factor in choosing whether to seek help for specific problems [73]. Crucially, as relationships with parents were also sometimes viewed as a contributing factor to stress in addition to being important sources of support, qualitative analyses showed that CYP with difficult relationships with parents were unlikely to view, and seek out, parents as a source of support [54] while qualitative evidence from 90 participants indicates support from both teachers and parents is prioritised by younger adolescents [74].

Knowledge and beliefs about professional help available

Between 40 and 75% of survey, cohorts believed mental illnesses were treatable by health professionals [34, 45, 50,51,52, 61, 63, 71, 72, 75] though individual studies varied in quality. Studying preferences more in depth found that formal help was considered comparatively more beneficial than none at all. However, CYP more often stated a preference to seek help from family, friends and traditional healers over mental health professionals [71, 75] though evidence was generated from two exploratory feasibility studies which were among the few that ranked the importance of different sources of professional help. In some studies, formal health services were considered more useful for physical health conditions such as diabetes compared to mental health problems, such as psychosis, depression and social phobia [42, 45, 46]. Among a sample of over 1000 Brazilian CYP those currently receiving or previously in receipt of psychological treatment had greater confidence in its usefulness [76] but overall, misgivings about the effectiveness of professional help were prominent.

Data regarding the perceived usefulness of health professionals and services were primarily derived from cross-sectional analyses using existing help-seeking measures. Health professionals were in the minority of identified sources of help but those that appeared salient included psychologists [42, 44, 46, 52], psychiatrists [42, 52, 61, 62, 75], GP [61, 62, 75] and school counsellors [42, 44, 56, 61, 75]. Less frequently, cardiologists/neurologists [69] and social workers [43] were considered key contacts. Limited understanding of the types of help available and the types of problems that might be treated by professionals emerged. CYP narrowly viewed help as individual counselling or psychotherapy [54, 68] without considering other professionals, types of therapy or formats for delivery. Where CYP were informed about the purpose of professional help, issues with infrastructure and provision were considered prominent barriers, i.e. lack of appropriate services or adequately trained professionals, long waiting times for treatment, limited availability of and resources within health services and health professionals not being interested in mental health problems [61, 69].

CYP instead highlighted the value attributed to religious and spiritual leaders and traditional healers in both qualitative and quantitative analyses [39, 50, 52, 54, 61, 62, 69, 75]. This group of paraprofessionals were often considered more helpful than professionals in formal health services [43, 59, 62] though it is important to recognise that evidence varied in quality. Preliminary evidence pointed to gender differences in views about professional helpfulness and there may be observable differences between males and females in help-seeking choices [46], but inquiry in this area is limited.

Factors and attitudes that facilitate recognition and help-seeking

Various facets of stigma were investigated, widely demonstrating that stigma levels are significant and shared by large proportions of CYP. Survey and pre-intervention data from separate studies in China, India, Iran, Pakistan, Vietnam and Cambodia found sizeable segments of CYP cohorts view people with mental health problems as dangerous/violent or frightening; proportions ranged from 25 to 80% [38, 40, 41, 44, 46, 51, 63]. Three separate studies recruiting smaller convenience samples for descriptive purposes or pre-intervention baseline analysis (range n = 67–205) in separate regions of Nigeria found high rates of similarly stigmatising beliefs [34, 47, 50]. For example, Dogra et al. [47] found 25% of respondents believed schizophrenia a split personality and a further 60% were unsure. People with mental illnesses are considered difficult to talk to [38, 47, 50, 77]; but furthermore, being associated with someone with a mental illness, or indeed seeking help for oneself, was considered shameful and embarrassing in between 11 and 67% of adolescent respondents [36, 44, 47, 63, 71].

Lack of confidence in professional treatment and fear of being stigmatised by others were statistically significant factors affecting help-seeking in hypothetical scenarios [76] supported by descriptive qualitative and quantitative evidence that despite the perceived usefulness in theory, adolescents felt challenged to use professionals because of stigma [54, 71]. Compared to those without, willingness to seek help was statistically significantly lower in adolescents with pre-existing mental health problems [36]. Self-stigma was determined the strongest predictor of willingness to seek help in exploratory models incorporating literacy, mental health status and help-seeking attitudes [48]. Path analysis determined self-stigma mediates the relationship between illness severity and help-seeking attempts [78]. Contradictory evidence was found in one study that personal stigma was higher among those with no current or past mental health problems [61]. Observing others who seek help being themselves stigmatised, and discriminating against professionals from whom they sought help, emerged consistently from qualitative accounts [54, 65, 68]. Interestingly, stigma was rarely examined in relation to actual or intended help-seeking and many of the studies analysed quantitative data from convenience samples of CYP.

Poor recognition is a significant barrier to help-seeking [76] and conversely, greater recognition of mental health problems is significantly correlated with increasing likelihood of help-seeking [53]. Comparing stigma levels between CYP in two or more locations was widely investigated demonstrating that stigma levels can vary between countries and even between regions of the same country [37,38,39,40, 61, 76, 79]. Evidence of both strong and weak quality contributed to this finding. Interestingly, there was some consensus that females had more positive attitudes to help-seeking [72, 73, 80, 81] and held less stigmatising attitudes than males [37, 47, 79] among mixed quality sources. Regarding depression, studies that did report this outcome, had mixed findings [54, 61] while other studies provided weaker evidence of no such gender differences [34, 38].

Knowledge of how to access mental health information

Minimal data were obtained from this review regarding CYP knowledge about how to access mental health information [33, 38, 40, 51]. Survey data highlighted the importance of family and friends as a specific source of information for a subset of Chinese CYP sampled in two separate studies [38, 40] with qualitative data from 19 Ugandan adolescents adding that experiencing mental health problems, either their own or witnessing this through family and friends, significantly enhanced their understanding [33]. Chinese adolescents accessed mental health information through TV/movies, newspaper, magazines, and school [38, 40] and Vietnamese high-school students highlighted the growing importance of technologies including the internet and helplines as a key source of mental health information [51]. There was variation across different sites in how different sources of information were prioritised [38, 40] but understanding of how CYP accessed mental health information from other LMICs was largely absent.

Discussion

This review analysed and synthesised empirical evidence regarding knowledge, beliefs and attitudes towards mental illness among CYP in LMICs drawing on Jorm’s framework for MHL. We found that knowledge of mental illnesses, treatments and help-seeking among populations in included studies was generally poor and that recognition of specific mental illnesses varied considerably in the studies that measured this outcome using vignette-based methods. Measures of general MHL, which delineate between assessments of individual knowledge separate from their beliefs [82], revealed a more consistent pattern of poor knowledge and low levels of awareness of mental health problems among CYP. We found evidence of pervasive stigma with high proportions of CYP endorsing statements signifying stigmatising attitudes towards those with mental illnesses. We also found some evidence of personal stigma and self-stigma which was linked with help-seeking propensity in a smaller number of studies. In terms of seeking out appropriate and effective help from formal sources, we found that seeking help from healthcare professionals was often not prioritised, however, knowledge of how to access formal help was limited and understudied. Instead, CYP cited the value of traditional healers as a mode of treatment and beneficial self-help practices for illness prevention supports the notion that social networks are an important source of mental health assistance in LMICs.

Methodological weaknesses were evident in included studies and the quality across studies varied significantly. Among quantitative analyses, fewer cross-sectional studies satisfactorily demonstrated obtaining a representative sample to evaluate the generalisability of their findings and many studies utilised measures of MHL, or some attribute, which did not have demonstrable cultural validity in the settings where they were administered. Similarly, the studies included using vignette-based approaches did not allow for direct comparison as there is no capacity to sum MHL levels or contrast between MHL domains [83]. Measures of general MHL, which incorporate knowledge and beliefs about mental illness terminology, causation, etiology, prognosis and course of illness are believed to overcome the limitations of vignette-based methodologies and more comprehensively address the MHL construct [82, 84]. However, these types of measures are also limited due to heterogeneity across measures, failure to incorporate validated constructs of knowledge, help-seeking and stigma [14] and a lack of specificity which arises from grouping a wide range of mental health problems together [85]. Importantly, these tools fail to reflect wide variability in cultural explanations for mental illness which we found in this review and establishing reliable and valid measures of MHL is important for future evaluations of MHL in different settings and contexts. There were additional conceptual limitations as most recognition studies focus on individual diagnosis, i.e. depression, rather than evaluating the range of possible mental illnesses or concerns that could be raised by CYP [18, 84, 85] or acknowledging that mental health conditions and outcomes are not universally valid across different cultures [86].

What can be clearly seen from the synthesised evidence is the dominance of stigmatised beliefs among CYP perspectives. Stigma emerged as a substantive concept underlying knowledge and beliefs across several domains of MHL incorporating negative beliefs about mental illnesses, risk factors and causation, self-help and professional help-seeking. Strong evidence emerged that CYP misconceptions that mental illnesses are caused by spiritual and religious forces, witchcraft, wizardry or sorcery as a result of perceived wrongdoing are pervasive and linked with beliefs that experiencing a mental illness is shameful and embarrassing [41, 51]. Cultural factors were found to influence beliefs and attitudes towards people with mental health problems and affect willingness to seek help [61, 71] and we also found evidence of geographical variation when high- and low-income settings were compared but also when regions within the same country were contrasted [37, 40]. Wider literature depicts theories of stigmatisation that highlight how stereotypical beliefs are linked with prejudice and discrimination [87] and clear evidence exists of the relationship between stigma, treatment avoidance and delay in seeking help [20, 23]. Evidence from multiple systematic reviews shows that attitudes and perceptions are particularly important in determining whether adolescents propose to seek professional help for a mental health problem [15, 16, 88]. Stigma, being ashamed and fearing negative evaluations by others are significant barriers to help-seeking [15, 16, 89]. However, research of this nature is primarily conducted in high-income settings supporting earlier assertions that the field is dominated by research from Western, developed nations [14]. There is a dearth of evidence from CYP in LMICs that help in understanding the role of stigma in help-seeking and pathways to receiving effective care [15, 16, 90]. The present review supports some existing findings that stigma influences help-seeking, but none of the included studies measured actual help-seeking. There was some evidence that both self-stigma and public stigma directly influence willingness to seek help [48, 78], but overall the relationship between stigma and help-seeking was under-researched.

As described above, CYP tended towards identifying spiritual and religious leaders and traditional healers as sources of professional support for mental health problems. We found some evidence that CYP attributed greater value to these sources of support than healthcare professionals who were less frequently prioritised. In many cultures, traditional and lay healers are recognised as legitimate sources of help and assume a substantial role in mental health care delivery [85, 86]. Knowledge of varied sources of professional help was mixed and limited to a small number of studies. A single source of evidence found that previous positive experiences with mental health professionals was a prominent facilitator of help-seeking among young people consistent with reviewed evidence [89] although this finding needs replicating as it may have particular salience for the development of social contact interventions to reduce stigmatisation of professional mental health services and increase help-seeking for effective treatment [88, 91].

Recommendations for future research

Several findings regarding the relationships between stigma, help-seeking and knowledge were restricted to individual studies in this review indicating the need to more fully evaluate attributes of MHL and evaluate interrelationships to more fully understand the interplay between knowledge, beliefs and attitudes across varied cultural settings. Campaigns focusing on improving mental health knowledge have consistently demonstrated that public awareness can be improved while changing negative attitudes about mental illness proves a more challenging target [92]. Although we found evidence of pervasive stigma, few studies meaningfully evaluated and captured the varied forms of stigma fully despite the need to appreciate the role of different types on individual help-seeking. Evidence shows that specific stigma types exert greater influence on active help-seeking than others [23] which is important for targeted stigma reduction campaigns aimed at promoting help-seeking. Comparable to the global literature, conceptualisation and measurement of facets of MHL theory concerning knowledge and beliefs about self-help and how to access mental health information for wellbeing in LMICs were less complete than other facets [14, 83]. Future research should focus on understanding the complexities of help-seeking, particularly active help-seeking exploring varied sources (informal, formal, self-help) and their relationship to the types of problems for which help is being sought. Additionally, a review of the current strategies used for stigma reduction, delivered and tested for their impact on CYP in LMICs, demonstrates that evidence-based interventions for these groups are disappointingly scarce [91]. Regarding sources of help, the value of collaborating with traditional healers needs greater exploration in younger populations in addition to appreciating the value of social networks to identify community platforms for educational interventions [93]. Community interventions are likely to have even greater relevance in low-resource settings [91, 94] whilst continuing to recognise the need to develop interventions across socio-ecological levels is key, particularly for child and adolescent populations [91].

Strengths and weaknesses

MHL theory has considerable utility as a structure for understanding and explicating factors that influence individuals help-seeking in relation to their mental health [82]; however, it has been described as an approximation of a theory [18]. Consensus has yet to be achieved regarding the dimensional structure of each MHL attribute [18, 85] and there is conceptual confusion regarding delineating the MHL construct and potential outcomes, appreciating what MHL is and what it is not, which have hampered coordinated research efforts [14]. Evidence indicates there are no tools that adequately evaluate all attributes and some measure additional constructs, such as knowledge and beliefs about course of illness, treatment outcome and recovery not included in original descriptions of the construct [82]. An important argument is that current theoretical approaches, whether measuring one or several MHL domains, fail to adequately and logically theorise the processes and mechanisms of action that link attitudes, intentions and behaviour [85]. We found that this lacking among the studies in the present review and similarly, we found no study that evaluated all facets of MHL which is important for developing research going forward. Another recent review, which focuses on MHL conceptualisation for adolescents, highlights similar constraints in that researchers purporting to examine MHL explored various adaptations and interpretations of the construct [14].

Another issue with measures denoting the assessment of knowledge is that they appear to tap into how individual respondents perceive illnesses to emerge and how they assess the usefulness of professional and lay forms of help [82]. Gauging whether respondents have the capacity including the necessary knowledge and skills to appraise the need for different types of help and prioritise help-seeking routes and strategies is often overlooked among assessments of MHL [82, 85] and is particularly pertinent to the inclusion of knowledge about self-management strategies [12]. Jorm’s theory [12] promotes self-management for minor problems but within conceptualisations of help-seeking which encompass illness behaviour, self-help can be understood to refer to how people monitor their own health, define and interpret their symptoms and take preventive or remedial action which may also incorporate using healthcare systems [85]. Essentially, the range of possible ways that people can triage their own mental health concerns and address these is not encompassed within this existing theory and should be considered for future conceptualisations of MHL constructs.

This review is strengthened by the use of a comprehensive search strategy, rigorous approach to screening, extraction and synthesis and guiding analysis with existing theory. The MMAT quality appraisal tool was employed to assess the quality of included studies highlighting significant variation in quality of published research in this area which can be considered a limitation. Developing culturally appropriate measures of MHL is key to enhancing the methodological rigour of research in LMICs while remaining sensitive to cultural variation in different settings. There is a potential for narrative synthesis to de-contextualise findings and we aimed to mitigate against this using a robust process for analysis underpinning synthesised data with in-depth qualitative findings where possible. Lastly, we identified that most studies in this synthesis did not include participants under the age of 10 despite including younger groups in our selection criteria. This may be due to the developmental aetiology of common mental illnesses where age of onset is concentrated in the middle and later stages of adolescence [5]. However, there is a need for research globally to understand and enhance mental health literacy for greater detection of childhood disorders [95] in addition to developing interventions for CYP.

Conclusion

This review highlights important issues regarding MHL for CYP in LMICs including low levels of recognition and knowledge about mental health problems and illnesses, pervasive levels of stigma and low confidence in professional healthcare services even when considered a valid treatment option. CYP cited the value of traditional healers and social networks for seeking help. There were several areas that were under-researched including the link between specific stigma types and active help-seeking and research is needed to understand more fully the interplay between knowledge, beliefs and attitudes across varied cultural settings. Greater exploration of social networks and the value of collaboration with traditional healers is consistent with promising, yet understudied, areas of community-based MHL intervention combining education and social contact.

Data statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Notes

DAC recipient countries are those eligible to receive official development assistance (ODA) based on gross national income (GNI) per capita as published by the World Bank.

References

Gore FM et al (2011) Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet 377(9783):2093–2102

World Bank Group (2018) World Development Indicators 2018. W.B. Group, Editor.

Kieling C et al (2011) Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. The Lancet 378(9801):1515–1525

Lu C, Li Z, Patel V (2018) Global child and adolescent mental health: The orphan of development assistance for health. PLoS Med 15(3):e1002524

Kessler RC et al (2007) Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry 20(4):359–364

Patton GC et al (2016) Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 387(10036):2423–2478

Thornicroft G et al (2017) Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. Br J Psychiatry 210(2):119–124

World Health Organization (2017) Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. World Health Organization, Geneva.

Saraceno B et al (2007) Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 370(9593):1164–1174

Volpe U et al (2015) The pathways to mental healthcare worldwide: a systematic review. Curr Opin Psychiatry 28(4):299–306

Jorm AF (2000) Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 177:396–401

Jorm AF (2012) Mental health literacy: empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am Psychol 67(3):231–243

Kutcher S et al (2016) Enhancing mental health literacy in young people. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 25(6):567–569

Mansfield R, Patalay P, Humphrey N (2020) A systematic literature review of existing conceptualisation and measurement of mental health literacy in adolescent research: current challenges and inconsistencies. BMC Public Health 20(1):607

Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H (2010) Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 10(1):113

Radez J, et al. (2020) Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur Child Adoles Psychiatry.

Andrade LH et al (2013) Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychol Med 44(6):1303–1317

Spiker DA, Hammer JH (2019) Mental health literacy as theory: current challenges and future directions. J Ment Health 28(3):238–242

Patel V et al (2018) The lancet commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet 392(10157):1553–1598

Henderson C, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G (2013) Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. Am J Public Health 103(5):777–780

Henderson C et al (2016) Public knowledge, attitudes, social distance and reported contact regarding people with mental illness 2009–2015. Acta Psychiatr Scand 134(S446):23–33

Schomerus G et al (2012) Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 125(6):440–452

Schnyder N et al (2017) Association between mental health-related stigma and active help-seeking: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 210(4):261–268

Bakkalbasi N et al (2006) Three options for citation tracking: Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science. Biomed Digit Lib 3:7–7

Page MJ et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71

Hong QN, et al. (2018) Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

Pace R et al (2012) Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud 49(1):47–53

Thomas J, Harden A (2008) Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 8(1):45

de Vet HCW et al (1997) Systematic reviews on the basis of methodological criteria. Physiotherapy 83(6):284–289

Popay J, et al. (2006) Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme. Version 1. Economic and Social Research Council, Swindon

Adelson E, et al. (2016) Sexual health, gender roles, and psychological well-being: voices of female adolescents from urban slums of India. In: Nastasi BK (Ed), pp 79–96.

Adelson E, et al. (2015) Sexual health, gender roles, and psychological well-being: voices of female adolescents from Urban Slums of India. In: Nastasi BK, Borja AP (eds) International handbook of psychological well-being in children and adolescents: bridging the gaps between theory, research, and practice. Springer, New York

Nalukenge W, et al. (2018) Knowledge and causal attributions for mental disorders in hiv-positive children and adolescents: Results from rural and urban uganda. Psychol Health Med 2018(Pagination): p. No Pagination Specified.

Ola B, Suren R, Ani C (2015) Depressive symptoms among children whose parents have serious mental illness: association with children’s threatrelated beliefs about mental illness. African J Psychiat (South Afr) 21(3):74–78

Gómez-Restrepo C, et al. (2021) Factors associated with the recognition of mental disorders and problems in adolescents in the National Mental Health Survey, Colombia. Colomb J Psychiatry. (in press)

Khalil A et al (2020) Self-stigmatization in children receiving mental health treatment in Lahore, Pakistan. Asian J Psychiatry 47:101839

Eskin M (1999) Social reactions of Swedish and Turkish adolescents to a close friend’s suicidal disclosure. Soc Psychiatry Psychiat Epidemiol 34(9):492–497

Yamaguchi S et al (2014) Stigmatisation towards people with mental health problems in secondary school students: an international cross-sectional study between three cities in Japan, China and South-Korea. Int J Cult Ment Health 7(3):273–283

Callan VJ, Wilks J, Forsyth S (1983) Cultural perceptions of the mentally ill: Australian and Papua New Guinean high school youth. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 17(3):280–285

Chan KF, Petrus Ng YN (2000) Attitudes of adolescent towards mental illness: a comparison between Hong Kong and Guangzhou samples. Int J Adolesc Med Health 12(2–3):159–175

Nguyen AJ, et al. (2020) Experimental evaluation of a school-based mental health literacy program in two southeast Asian Nations. School Mental Health

Aluh DO et al (2018) Mental health literacy: what do Nigerian adolescents know about depression? Int J Ment Heal Syst 12:8

Aggarwal S et al (2016) South African adolescents’ beliefs about depression. Int J Soc Psychiatry 62(2):198–200

Sharma M, Banerjee B, Garg S (2017) Assessment of mental health literacy in school-going adolescents. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health 13(4):263–283

Attygalle UR, Perera H, Jayamanne BDW (2017) Mental health literacy in adolescents: ability to recognise problems, helpful interventions and outcomes. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 11:38

Essau CA et al (2013) Iranian adolescents’ ability to recognize depression and beliefs about preventative strategies, treatments and causes of depression. J Affect Disord 149(1–3):152–159

Dogra N et al (2012) Nigerian secondary school children’s knowledge of and attitudes to mental health and illness. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 17(3):336–353

Ibrahim N et al (2019) Do depression literacy, mental illness beliefs and stigma influence mental health help-seeking attitude? A cross-sectional study of secondary school and university students from B40 households in Malaysia. BMC Public Health 19(4):544

Ibrahim N et al (2020) The effectiveness of a depression literacy program on stigma and mental help-seeking among adolescents in Malaysia: a control group study with 3-month follow-up. Inquiry 57:0046958020902332

Oduguwa AO, Adedokun B, Omigbodun OO (2017) Effect of a mental health training programme on Nigerian school pupils’ perceptions of mental illness. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 11:19

Thai TT, Vu NLLT, Bui HHT (2020) Mental health literacy and help-seeking preferences in high school students in Ho Chi Minh City Vietnam. School Mental Health 12(2):378–387

Williams DJ (2012) Where do Jamaican adolescents turn for psychological help? Child Youth Care Forum 41(5):461–477

Gómez-Restrepo C et al (2021) Associated factors for recognition of mental problems and disorders in adolescents in the Colombian National Mental Health Survey. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr 50(1):3–10

Dardas LA et al (2019) Depression in Arab adolescents: a qualitative study. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 57(10):34–43

Ronzoni P et al (2010) Stigmatization of mental illness among Nigerian schoolchildren. Int J Soc Psychiatry 56(5):507–514

Willenberg L et al (2020) Understanding mental health and its determinants from the perspective of adolescents: a qualitative study across diverse social settings in Indonesia. Asian J Psychiatr 52:102148

Nguyen DT et al (2013) Perspectives of pupils, parents, and teachers on mental health problems among Vietnamese secondary school pupils. BMC Public Health 13:1046

Suttharangsee W (1997) Concepts and protective factors related to positive mental health from Thai adolescents’ perspectives: an ethnonursing study. Dissert Abstr Int Sect B Sci Eng 58(6B):2963

Bella T et al (2012) Perceptions of mental illness among Nigerian adolescents: an exploratory analysis. Int J Cult Ment Health 5(2):127–136

Morais CA et al (2012) Brazilian young people perceptions of mental health and illness. Estudos de Psicologia 17(3):369–379

Dardas LA (2018) A nationally representative survey of depression symptoms among Jordanian adolescents: Associations with depression stigma, depression etiological beliefs, and likelihood to seek help for depression. Dissert Abstracts Int Sect B Sci Eng 78(9-B(E)): p. No Pagination Specified.

Dhadphale M (1979) Attitude of a group of Zambian females to spirit possession (Ngulu). East Afr Med J 56(9):450–453

Rahman A et al (1998) Randomised trial of impact of school mental-health programme in rural Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Lancet 352(9133):1022–1025

Tamburrino I et al (2018) Everybody’s responsibility: conceptualization of youth mental health in Kenya. J Child Health Care 24(1):5–18

Jenkins JH, Sanchez G, Lidia Olivas-Hernández O (2019) Loneliness, adolescence, and global mental health: soledad and structural violence in Mexico. Transcult Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461519880126

Glozah FN (2015) Exploring Ghanaian adolescents’ meaning of health and wellbeing: A psychosocial perspective. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v10.26370

Secor-Turner M, Randall BA, Mudzongo CC (2016) Barriers and facilitators of adolescent health in rural Kenya. J Transcult Nurs 27(3):270–276

Parikh R et al (2019) Priorities and preferences for school-based mental health services in India: a multi-stakeholder study with adolescents, parents, school staff, and mental health providers. Global Mental Health 6:e18

Paula CS et al (2009) Primary care and children’s mental health in Brazil. Acad Pediatr 9(4):249-255.e1

Estrada CAM et al (2019) Suicidal ideation, suicidal behaviors, and attitudes towards suicide of adolescents enrolled in the alternative learning system in Manila, Philippines-a mixed methods study. Trop Med Health 47:22

Maloney CA, Abel WD, McLeod HJ (2020) Jamaican adolescents’ receptiveness to digital mental health services: a cross-sectional survey from rural and urban communities. Internet Interv 21:100325

Jackson DN (2007) Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help among Jamaican adolescents. Dissert Abstr Int Sect B Sci Eng 67(8B):4711

Yilmaz-Gozu H (2013) The effects of counsellor gender and problem type on help-seeking attitudes among Turkish high school students. Br J Guid Couns 41(2):178–192

Yu C et al (2019) Young internal migrants’ major health issues and health seeking barriers in Shanghai, China: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 19(1):336

Dardas LA et al (2018) Studying depression among Arab adolescents: methodological considerations, challenges, and lessons learned from Jordan. Stigma Health 3(4):296–304

Fukuda CC et al (2016) Mental health of young Brazilians: barriers to professional help-seeking. Estudos de Psicologia 33(2):355–365

Bella-Awusah T et al (2014) The impact of a mental health teaching programme on rural and urban secondary school students’ perceptions of mental illness in Southwest Nigeria. J Child Adolesc Ment Health 26(3):207–215

Chen H et al (2014) Associations among the number of mental health problems, stigma, and seeking help from psychological services: a path analysis model among Chinese adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev 44:356–362

Ndetei DM et al (2016) Stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness among primary school children in Kenya. Soc Psychiatry Psychiat Epidemiol 51(1):73–80

Abdollahi A et al (2017) Self-concealment mediates the relationship between perfectionism and attitudes toward seeking psychological help among adolescents. Psychol Rep 120(6):1019–1036

Williams DJ (2014) Help-seeking among Jamaican adolescents: an examination of individual determinants of psychological help-seeking attitudes. J Black Psychol 40(4):359–383

O’Connor M, Casey L, Clough B (2014) Measuring mental health literacy—a review of scale-based measures. J Ment Health 23(4):197–204

O’Connor M, Casey L, Clough B (2014) Measuring mental health literacy—a review of scale-based measures. J Ment Health 23(4):197–204

Kutcher S, Wei Y, Coniglio C (2016) Mental health literacy: past, present, and future. Can J Psychiatry 61(3):154–158

Rickwood D, Thomas K (2012) Conceptual measurement framework for help-seeking for mental health problems. Psychol Res Behav Manag 5:173–183

Nortje G et al (2016) Effectiveness of traditional healers in treating mental disorders: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 3(2):154–170

Wei Y et al (2018) The quality of mental health literacy measurement tools evaluating the stigma of mental illness: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 27(5):433–462

Aguirre Velasco A et al (2020) What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 20(1):293

Rickwood D et al (2005) Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Aust e-J Adv Mental Health 4(3):218–251

MacDonald K et al (2018) Pathways to mental health services for young people: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 53(10):1005–1038

Hartog K et al (2020) Stigma reduction interventions for children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review of intervention strategies. Soc Sci Med 246:112749

Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Schomerus G (2013) Attitudes towards psychiatric treatment and people with mental illness: changes over two decades. Br J Psychiatry 203(2):146–151

Renwick L et al (2021) Conceptualisations of positive mental health and wellbeing among children and adolescents in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Health Expect. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13407

Kohrt BA et al (2018) The role of communities in mental health care in low- and middle-income countries: a meta-review of components and competencies. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(6):1279

Tully LA et al (2019) A national child mental health literacy initiative is needed to reduce childhood mental health disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 53(4):286–290

Acknowledgements

This paper presents independent research funded by the Medical Research Council (MR/R022151/1) under its Research Grant Scheme titled Improving Mental Health Literacy Among Young People aged 12-15 years in Indonesia: IMPeTUs. Additional support was provided by the Division of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work at the University of Manchester. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Medical Research Council or the University of Manchester.

Funding

This paper presents independent research funded by the Medical Research Council (MR/R022151/1) under its Research Grant Scheme titled Improving Mental Health Literacy Among Young People aged 12–15 years in Indonesia: IMPeTUs. Additional support was provided by the Division of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work at the University of Manchester. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LR, RP and HB drafted the manuscript, LR was responsible for organisation and preparation of manuscript, LR, RP, IJ, HB, VB, KL and HB were responsible for the concept of the review and PB and HB conceived of the overall study from which the review was conducted, IJ with oversight from HB, PB, RP and KL developed and managed the search strategy, LR, HB, RP and VB were responsible for data extraction and analysis was conducted by LR, HB and RP with input from the wider review team for analysis planning, interpretation of data and overall manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Reflexivity statement

LR is a Senior Lecturer in Mental Health Nursing, HB a Senior Lecturer in Health Services Research, PB a Professor of Health Services Research, KL a Professor in Mental Health, IJ a Psychology Researcher, VB a Research Fellow and RP a Senior Research Fellow. The starting point for the research was one informed by the value of mental health literacy for children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries recognising that deficit approaches need to be evaluated and considered for their usefulness in these settings. We also took a position that positive views of mental health contribute to how mental health perceptions are constructed and may influence access and treatment. Analysis and synthesis were conducted primarily by LR, HB and RP with significant experience of evidence synthesis and both quantitative and qualitative research.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Renwick, L., Pedley, R., Johnson, I. et al. Mental health literacy in children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: a mixed studies systematic review and narrative synthesis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33, 961–985 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-01997-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-01997-6