Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to see the effect of Er:YAG laser irradiation in dentine and compare this with its effect in enamel. The mechanism of crack propagation in dentine was emphasised and its clinical implications were discussed.

Materials and methods

Coronal sections of sound enamel and dentine were machined to 50-μm thickness using a FEI-Helios Plasma (FIB). The specimen was irradiated for 30 s with 2.94-μm Er:YAG laser radiation in a moist environment, using a sapphire dental probe tip, with the tip positioned 2 mm away from the sample surface. One of the sections was analysed as a control and not irradiated. Samples were analysed using the Zeiss Xradia 810 Ultra, which allows high spatial resolution, nanoscale 3D imaging using X-ray computed tomography (CT).

Results

Dentine: In the peritubular dentine, micro-cracks ran parallel to the tubules whereas in the inter-tubular region, the cracks ran orthogonal to the dentinal tubules. These cracks extended to a mean depth of approximately 10 μm below the surface. On the dentine surface, there was preferential ablation of the less mineralised intertubular dentine, and this resulted in an irregular topography associated with tubules.

Enamel: The irradiated enamel surface showed a characteristic ‘rough’ morphology suggesting some preferential ablation along certain microstructure directions. There appears to be very little subsurface damage, with the prismatic structure remaining intact.

Conclusions

A possible mechanism is that laser radiation is transmitted down the dentinal tubules causing micro-cracks to form in the dentinal tubule walls that tend to be limited to this region.

Clinical relevance

Crack might be a source of fracture as it represents a weak point and subsequently might lead to a failure in restorative dentistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dental hard tissues are organised in a three-dimensional and hierarchical manner and exhibit anisotropic mechanical properties [1,2,3]. Enamel and dentine also have heterogeneity of structure, and the variation in structure and mechanical properties may influence the direction of crack progression [4].

Laser radiation of dental hard tissues usually results in the observation of cracks. Previous studies using scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging explored the presence of cracks formed with high laser powers, CO2 lasers or when irradiated in a dry environment [5, 6], and are therefore not clinically applicable. Yamada et al. [7] reported that the irradiation of dentine with a CO2 laser resulted in cracks that were mostly in the peritubular dentine. Burkes et al. [8] stated that enamel tissue following Er:YAG laser radiation showed cracks in a dry environment, but no cracks were seen in the wet condition.

The orientation of collagen fibres appears to be particularly significant for the overall dental tissue strength and damage resistance [9, 10]. In the peritubular dentine, the collagen fibres are arranged parallel to the long axis of dentinal tubules, whereas, in the intertubular dentine, the fibres are perpendicular to the dentinal tubules. X-ray diffraction studies have been used to study the structure of collagen fibres, but are difficult to relate to function as they show no preferred orientation of the apatite crystals, with a lack of alignment between crystals in adjacent fibrils. Therefore, fracture behaviour in dentine may be dominated by the collagen fibril direction rather than the orientation of the apatite crystals [11].

The thermo-physical characteristics of a tooth vary between the enamel and dentine and even in the individual dental layer; they are anisotropic and inhomogeneous [12]. The thermal conductivity of heterogeneous substances like a human tooth is greatly influenced by its structure and composition [13]. Lin et al. [12] reported that the thermal conductivity of human dentine expressed a weak anisotropy, which might be attributed to the presence of dentinal tubules. The literature reports various values of thermal behaviour of enamel and dentine, which may be attributed to the different design of experiments and scales. However, they agree that the thermal conductivity and diffusivity of dentine are less than that of enamel [12, 14,15,16].

Tissue interactions with pulsed lasers can be characterised by the thermal relaxation time, τr given by \( {\tau}_r=\frac{1}{4\chi {\mu}_a^2} \), where χ is the thermal diffusivity and μa is the absorption coefficient. The thermal diffusivity is also given by \( \chi =\frac{\kappa }{C\rho} \), where κ is the thermal conductivity, C the thermal heat capacity and ρ is the density. Table 1 shows the values of these parameters for dentine, enamel and water. As can be seen in each case, the thermal relaxation time is much less than the pulse length of the laser used (~ 800 μs), and hence, the interaction is thermally driven and there can be some thermal damage to the surrounding tissue.

However, the X-ray nano-CT allows high-resolution examination of cracks at the nanoscale, revealing the extent of nano-cracks due to laser irradiation in dental hard tissues. Using the ZEISS Xradia 810 Ultra X-ray microscope, we were able to achieve spatial resolution down to 50 nm [17]. Nano-CT offers the requisite three-dimensional (3D) spatial resolution for studying dentinal tubules and canaliculi [18]. It is a technique that permits reconstruction of the 3D internal structure of an object without any preparation, by acquiring X-ray projections from different viewing angles ranging from 0 to 180°. Then, the artefact-free 3D structure of the object can be acquired using a reconstruction algorithm [19, 20].

The aim of this work was to examine the effect of Er:YAG laser radiation on the 3D ultrastructure of moist human enamel and dentine. Using a laser allowed a defined amount of energy to be applied to the material surfaces in a defined direction. The thermo-mechanical effects and ablative effects of the energy parameters used in the experiments were carefully defined. The amount of ablated tissue following laser radiation was evaluated using a confocal microscope technique, and subsurface nano-cracks were characterised using nano-CT. The null hypothesis to be tested is that there is no difference in the effect of Er:YAG laser between enamel and dentine tissues.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

Four human permanent premolar teeth were collected from anonymous dental-care patients and stored as required under the UK Human Tissue Act 2004. The teeth samples were sectioned transversally in 0.1-mm thick discs using the IsoMet® 1000 Precision Saw (Isomet 1000, Buehler, USA). Then, each slice was ground and polished with silicon carbide (SiC) paper of no. 4000-grit (Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, IL, USA) to obtain a uniform thickness of 50 μm. Three sections were used for each dental hard tissue.

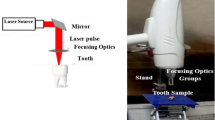

Since the ideal specimen size for the X-ray nano-CT is controlled by the X-ray energy and its transmission, the FEI Helios Plasma FIB machine (PFIB) was used to manufacture specimens of an ideal size after laser irradiation. This technique provides precise machining with low significant damage artefacts [21]. The sample was milled perpendicular to the ablated surface until an area 50 μm wide and 70 μm high remained protruding from the top of the sample. The specimens were about 50 μm thick (Fig. 1).

Laser irradiation

The same laser parameters were used for ablation of enamel and dentine to allow a comparison of the effects on the two tissues. The tissue slices were ablated with an Er:YAG laser (Fidelis Surgical Laser Model 320A Er:YAG Fotona Medical Lasers) emitting at a wavelength of 2.94 μm, with energy density (fluence) 8.42 J/cm−2, pulse energy of 100 mJ and repetition rate of 15 Hz for 30 s. The laser radiation was delivered to the tissue via a sapphire probe tip. The laser was working in the very long pulse mode (750-950 μs). The samples were kept moistened.

Additionally, one sample for each dental hard tissue was analysed by confocal microscopy (LSM510Meta) to define the volume of ablated material following Er:YAG laser radiation.

Nano-CT imaging

Two samples were used for each dental hard tissue. One each was irradiated with the Er:YAG laser, with the others acting as controls. The tissues were examined with the Zessis Xradia 810 Ultra, a lab based X-ray CT instrument using 5.4 kV energy X-rays that are focussed using a Fresnel zone plate. The nano-CT was operated in the large field of view phase contrast mode, in which a Zernike phase ring provides phase contrast, in addition to the absorption contrast mode. The spatial resolution of both modes is approximately 50 nm.

Reconstruction was performed in the Zeiss Xradia XMReconstructor software (version 9.1.12862), using their proprietary back projection based reconstruction algorithm.

Fractures and other features in the specimen (e.g. dentinal tubules) could be identified and followed in three dimensions in the specimens.

Data analysis

Three-dimensional segmentation and analysis of the specimens were performed using Avizo software (version 9.2.0, Thermo Fischer Scientific). The data was filtered using a non-local means filter with a kernel size of 21. Segmentation of the cracks was performed predominantly manually.

LSM510Meta confocal microscopy

This microscope has three types of lasers with three fluorescence detectors including META detector. It is capable of spectral imaging, which is useful for detaching overlapping fluorophores. In the front of each detector of the LSM 510META, there are pinholes that can be beneficial for matching of confocal section thicknesses between varied colours or more precise autofocus.

Results

Impact of Er:YAG laser radiation on the surface of dentine and enamel microstructure

Dentine

In the dentine, the Er:YAG laser irradiated surface possessed a large number of nano-scale cracks (Fig. 2). There was a high density of cracks close to the surface but there were not observable in the scanning electron microscope (SEM). From the X-ray CT, cracks to a depth of approximately 10 μm from the irradiated surface were observed. The dentine close to the surface also appears to have a different internal texture (i.e. mottled appearance in the nano-CT) versus deeper into the sample, possibly indicating a damaged structure. On the dentine surface, the peritubular dentine was more prominent than in the surrounding inter-tubular dentine, probably due to preferential ablation of the inter-tubular dentine.

a Volume rendering of a number of dentinal tubule lumens at the surface of the dentine matrix. b Tubule features extending in one direction throughout the sample are clearly observed as dark ‘lines’ in the sagittal image. Cracks are observed within 20 μm of the irradiated surface. Radial and interfacial cracks are seen. c SEM images of control dentine showed open and occluded dentinal tubules. d All dentinal tubules of irradiated dentine are opened with no smear layer covering them

The control dentine showed open and occluded dentinal tubules under the SEM. In the irradiated dentine, all dentinal tubules are opened with no smear layer covering them. The occlusion is believed to be created from polishing debris during preparation (see Fig. 2).

Enamel

The reconstructed nano-CT data shows that the irradiated enamel surface possesses a characteristic “rough” morphology (see Fig. 3). There appears to be little subsurface damage, although a few isolated cracks are visible, they do not appear consistent enough to be due to the irradiation. The prismatic structure appears to still extend up to the surface although the increased intensity visible at the surface could indicate evidence of a denser surface within the top few hundred nanometres. This may be due to melting and subsequent cooling of the enamel. The SEM image showed a smooth surface of control enamel, whereas the lased enamel showed a flat glazed area (Fig. 3).

a Volume rendering of X-ray CT of enamel and bXY slice from the nano-CT reconstruction of irradiated enamel. The laser-irradiated enamel surface possesses a characteristic ‘rough’ morphology with some cracks. The rod structure appears to still extend up to the surface although there is some evidence of a denser surface within the top few hundred nanometres. c SEM image of control sample expressed a smooth surface, which under higher magnification appears not to be totally smooth. d Irradiated enamel showed changes in surface smoothness (i.e. a rough morphology). The prismatic structure showed some flat glazed area

Nano-CT of control enamel and dentine showed the normal structure of dental hard tissues.

Three-dimensional analysis of cracks

Cracks were observed in both inter-tubular and peritubular regions of dentine, but each region displayed distinct differences in depth and direction of crack propagation. The peritubular region possessed cracks that had a plane parallel to the direction of the tubules. i.e. bisected the peritubular ‘cuff’ (Fig. 4). Cracks in the inter-tubular region propagated in a plane parallel to the direction of the collagen fibres, showing a preference to propagate around dentinal tubules (Fig. 4), rather than through the peritubular dentine (Fig. 4). Cracks were also observed at the boundary between the peritubular and intertubular dentine, following the direction of the tubule (Fig. 4). The cracks observed within the peritubular dentine extended to a mean depth of 10 ± 7 μm (SD) and in the matrix extended to a mean depth of 7 ± 4 μm (SD). Each measurement was taken from 70 different locations.

Three dimensional (3D) volume renderings of reconstructed segmented dentine illustrating the dentinal tubules and cracks. The crack plane can be seen to extend at right angles to the length of the tubules, although occasionally intersecting the tubules (upper). In the lower images, a one tubule with its associated peritubular dentine and cracks were segmented. The crack passes around the tubule but can be seen to join cracks in the peritubular dentine that cut across the cross-section of the tubule (lower). Dentinal tubule (blue), peritubular dentine (yellow) and cracks (red)

Determination of the volume of material removed

Confocal microscopy showed that the Er:YAG laser radiation removed more volume of dentine than enamel tissue. The volume of dentine that was removed following laser irradiation was 0.0091 mm3, over an area of 0.506 mm2 (Fig. 5).

In enamel, the volume ablated could not be measured by confocal microscopy as it was too small. The confocal microscopy has a high resolution in the X, Y and Z directions.

Discussion

Previous studies of irradiation damage in dental tissues have been performed with approaches unable to observe the 3D structure such as transmission electron microscope (TEM) and SEM imaging. These techniques only permit localised observation of the surface [17].

The irradiated dentine revealed many nanoscale-cracks that were mainly concentrated in the peritubular dentine. Some of them were confined to the mineralised ring of the peritubular dentine. Our cracks also extended into the intertubular dentine. Cracks resulting from laser irradiation are usually the result of elastic waves that are generated in the solid target tissue because of the transient thermal shock produced by the intense and local laser heating, thermal expansion and the ablation product recoiling [5, 22, 23]. The peritubular area has a higher content of hydroxyapatite than that of intertubular dentine and is brittle and more vulnerable to crack formation with the thermal shock of laser irradiation [7]. In the three-dimensional view, the cracks can be seen to follow the direction of the mineralised collagen fibres in the inter-tubular dentine but are perpendicular in the peritubular region. The cracks progressed along the tubules (Fig 4).

The crack pattern in our study was localised to the surface, with a mean depth that did not exceed 10 μm and with the cracks appearing somewhat irregular at first look. In another study by Staninec et al. [24], the cracks were created following irradiation with an Er-Cr-YSGG laser in a dry environment and different laser parameters extending to a depth in the range of 131–300 μm. Another study used a diamond cone indenter to mechanically initiate and propagate cracks in elephant dentine (tusk) and reported that the direction of crack propagation was perpendicular to the dentinal tubule axis [17]. The explanation for the different results might be attributed to differences in the structure and composition between elephant and human dentine, but also, the method of crack production varied between studies. The tubules of elephant dentine are elliptical and larger than the round tubules of human dentine. The collagen fibrils and the extent of the peritubular dentine in tusks are smaller than those in human dentine. In ivory, the collagen fibrils are oriented perpendicular to the dentinal tubules and parallel to the long axis of the tooth [25]. In tusk, some of the tubules are filled with carbonated hydroxyapatite which is unlike the case with human dentine. The tubules are arranged over each other axially to form microlaminae. The shape, position and orientation of dentinal tubules into microlaminae are variable for each type of ivory and they can be straight or form wavy structures. The orientation of the tubules can also be different between the adjacent microlaminae [26].

During laser irradiation, a local rise in temperature is distributed in a non-uniform way throughout the enamel and dentine. Attrill et al. [27] reported that the temperature excursion was directly related to the total delivered energy, which is only applicable during continuous irradiation. A critical temperature threshold of 5.6 °C was defined as the temperature that is safe for pulp tissue in the presence of water using different parameters. They also showed that a quantifiable estimate of temperature increase can be calculated by following the linear regression equation:

where ΔTmax is the peak temperature increment (°C) and E is the cumulative energy input (J).

According to this equation, the temperature rise in our study is 0.87 °C, but this describes the overall temperature increase of the tissue. The instantaneous localised temperature increase will be much higher than this. It is known that the interaction mechanism of Er:YAG laser radiation on hard tissues is mediated by rapid heating of water, which creates enormous subsurface pressures leading to explosive removal of material [28]. This mechanism might be a source of the cracks seen in our study. As seen in Fig. 4, cracks are clear in the irradiated dentine which has a higher water content than enamel tissue. Water has the highest absorption coefficient and it is therefore likely that any water present will drive the interaction. In this study, the dentine was kept moist during exposure and as such the tubules would be expected to be filled with water during irradiation. The mechanism for crack propagation is proposed to be due to the rapid expansion of water vapour in the dentinal tubules leading to micro explosion pressure and the formation of the radial cracks, which propagate through the peritubular dentine and into the intertubular dentine. The cracks are more prominent in peritubular dentine since it is denser and more brittle than intertubular dentine. Forein et al. [9] investigated the interaction of human dentine mineral nanoparticles and collagen fibres under humidity-driven stress with heating up to 125 °C. Forein et al. showed (as in our experiment) that the nano-composite structure of dentine hinders the propagation of cracks and diverts them in directions orthogonal to the mineralised inter-tubular collagen layers. The tubules may disrupt propagation of the crack through the dentine, disrupting its spread and directing it along the length of the tubule, which is less damaging to the overall performance of the tooth.

According to Table 1, this goes some way to explaining the different results observed between enamel and dentine with the same amount of laser energy used on both. In this study, the nano-CT of irradiated enamel does not show cracks similar to that of the irradiated dentine. Also, the different structure leads to a varied dissipation of heat. In addition, despite also being kept moist during irradiation, the enamel will not contain internal volumes of water in the same way that the tubules in dentine can. Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected.

The rapid expansion of water in the dentinal tubules is considered to be responsible for crack initiation in the peritubular region and at the interface between peritubular and intertubular regions in dentine. The cracks progress along the interface region then propagate into the intertubular matrix, thus propagating along planes parallel to that of the tubules.

Conclusion

The following conclusions can be drawn:

-

(1)

Laser irradiation of moist enamel with our parameters resulted in a relatively small amount of material removal and no observable sub-surface damage under the conditions used.

-

(2)

Laser irradiation of moist dentine resulted in a much more rapid rate of material removal than observed in the enamel and created sub-surface damage up to a depth of approximately 10 μm.

-

(3)

Nano-scale cracks were observed in laser-irradiated dentine that were concentrated in the peritubular region but extended into the intertubular matrix. The peritubular dentine around the tubules prevented cracks from propagating uninterrupted in to the matrix, redirecting them along the length of the tubule.

-

(4)

The damaged surface of laser-irradiated dentine may be unsuitable for subsequent bonding as the top surface may be prone to delamination due to subsurface cracks, although this process has not been investigated in this study.

-

(5)

The evidence supported the mechanism of crack propagation as being caused by water vaporisation causing a pressure wave that resulted in crack formation in the near-surface of the irradiated dentine.

References

Shahmoradi M, Bertassoni LE, Elfallah HM, Swain M (2014) Fundamental structure and properties of enamel, dentin and cementum, in advances in calcium phosphate biomaterials. In: Ben-Nissan B (ed) Advances in calcium phosphate biomaterials. Springer, Berlin, pp 511–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-53980-0_17

Ţălu Ş, Contreras-Bulnes R, Morozov IA, Rodríguez-Vilchis LE, Montoya-Ayala G (2015) Surface nanomorphology of human dental enamel irradiated with an Er:YAG laser. Laser Phys 26(2):025601. https://doi.org/10.1088/1054-660X/26/2/025601

Müller B, Deyhle H, Bradley DA, Farquharson M, Schulz G, Müller-Gerbl M, Bunk O (2010) Nanomethods: scanning X-ray scattering: evaluating the nanostructure of human tissues. Eur J Nanomedicine 3(1):30–33. https://doi.org/10.1515/EJNM.2010.3.1.30

Earl J, Leary RK, Perrin JS, Brydson R, Harrington JP, Markowitz K, Milne SJ (2010) Characterization of dentine structure in three dimensions using fib-sem. J Microsc 240(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2818.2010.03396.x

Staninec M, Meshkin N, Manesh SK, Ritchie RO, Fried D (2009) Weakening of dentin from cracks resulting from laser irradiation. Dent Mater 25(4):520–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2008.10.004

Nokhbatolfoghahaie H, Chiniforush N, Shahabi S, Monzavi A (2012) Scanning electron microscope (SEM) evaluation of tooth surface irradiated by different parameters of erbium: yttrium aluminium garnet (Er: YAG) laser. J Lasers Med Sci 3(2):51–S18. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.17643686

Yamada MK, Uo M, Ohkawa S, Akasaka T, Watari F (2004) Non-contact surface morphology analysis of CO2 laser-irradiated teeth by scanning electron microscope and confocal laser scanning microscope. Mater Trans 45(4):1033–1040. https://doi.org/10.2320/matertrans.45.1033

Burkes EJ, Hoke J, Gomes E, Wolbarsht M (1992) Wet versus dry enamel ablation by Er: YAG laser. J Prosthet Dent 67(6):847–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3913(92)90599-6

Forien JB, Fleck C, Cloetens P, Duda G, Fratzl P, Zolotoyabko E, Zaslansky P (2015) Compressive residual strains in mineral nanoparticles as a possible origin of enhanced crack resistance in human tooth dentin. Nano Lett 15(6):3729–3734. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b00143

Forien JB, Zizak I, Fleck C, Petersen A, Fratz P, Zolotoyabko E, Zaslansky P (2016) Water-mediated collagen and mineral nanoparticle interactions guide functional deformation of human tooth dentin. Chem Mater 28(10):3416–3427. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b00811

Wang R, Weiner S (1998) Human root dentin: structural anisotropy and Vickers microhardness isotropy. Connect Tissue Res 39(4):269–279. https://doi.org/10.3109/03008209809021502

Lin M, Liu QD, Kim T, Xu F, Bai BF, Lu TJ (2010) A new method for characterization of thermal properties of human enamel and dentine: influence of microstructure. Infrared Phys Technol 53(6):457–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2010.09.004

Carson JK, Lovatt SJ, Tanner DJ, Cleland AC (2005) Thermal conductivity bounds for isotropic, porous materials. Int J Heat Mass Transf 48(11):2150–2158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2004.12.032

Brown W, Dewey W, Jacobs H (1970) Thermal properties of teeth. J Dent Res 49(4):752–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345700490040701

Braden M (1964) Heat conduction in teeth and the effect of lining materials. J Dent Res 43(3):315–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345640430030201

Craig R, Peyton F (1961) Thermal conductivity of tooth structure, dental cements, and amalgam. J Dent Res 40(3):411–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345610400030501

Bradley RS, Lu X (2015) In situ 3D Imaging of Crack Growth in Dentin. University of Manchester. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/65ec/4ed63df3135c8da1fe84a91fdb51cf651ba9.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2017

He P, Wei B, Wang S, Stock SR, Yu H, Wang G (2013) Piecewise-constant-model-based interior tomography applied to dentin tubules. Comput Math Methods Med 2013:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/892451

Mouze D, Patat JM, Rondot S, Sasov A, Trebbia P, Zolfaghari A (1993) Recent developments in X-ray projection microscopy and X-ray micro-tomography applied to materials sciences. J Phys IV 7:2099–2105. https://doi.org/10.1051/jp4:19937334

Wevers M, Kerckhofs G, Pyka G, Herremans E, Van Ende A, Hendrickx R, Verstrynge E, Mariën A, Valcke E, Pareyt B. (2012). X-ray computed tomography for nondestructive testing. in International Conference on Industrial Computed Tomography. http://hdl.handle.net/2268/161701

Burnett TL, Winiarski B, Kelley R, Zhong XL, Boona IN, McComb DW, Mani K, Burke MG, Withers PJ (2016) Xe+ plasma FIB: 3D microstructures from nanometers to hundreds of micrometers. Microscopy Today 24(03):32–39. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1551929516000316

Motamedi M, Rastegar S, and Anvari B. (1992). Thermal stress distribution in laser-irradiated hard dental tissue: implications for dental applications. Polymers Laminations and Coatings Conference TAPPI Press. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.137474

Vogel A, Venugopalan V (2003) Mechanisms of pulsed laser ablation of biological tissues. Chem Rev 103(2):577–644. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr010379n

Staninec M, Meshkin N, Manesh SK, Ritchie RO, Fried D (2005) Weakening of dentin from cracks resulting from laser irradiation. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 7(1):2S1–2S7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2008.10.004

Lafrenz KA (2004) Tracing the source of the elephant and hippopotamus ivory from the 14th century BC Uluburun shipwreck: the archaeological, historical, and isotopic evidence. Dissertation, University of South Fluorida. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1122

Lu X (2015) Characterisation of the anisotropic fracture toughness and crack-tip shielding mechanisms in elephant dentin. Dissertation, University of Manchester. https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/54575584/FULL_TEXT.PDF

Attrill DC, Davies RM, King TA, Dickinson MR, Blinkhorn AS (2004) Thermal effects of the Er: YAG laser on a simulated dental pulp: a quantitative evaluation of the effects of a water spray. J Dent 32(1):35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-5712(03)00137-4

Lizarelli RFZ, Moriyama LT, Jorge JR, Bagnato VS (2006) Comparative ablation rate from a Er: YAG laser on enamel and dentin of primary and permanent teeth. Laser Phys 16(5):849–858. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1054660X06050173

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was given for the experiments. Patient consent was obtained for the teeth to be retained following extraction for unrelated purposes. The teeth were stored under the Human Tissue Authorisation at the University of Manchester in United Kingdom.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

(AVI 55636 kb)

ESM 2

(AVI 119714 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Aljdaimi, A., Devlin, H., Dickinson, M. et al. Micron-scale crack propagation in laser-irradiated enamel and dentine studied with nano-CT. Clin Oral Invest 23, 2279–2285 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2654-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2654-0