Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the survival of single- and two-surface atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) restorations in the primary and permanent dentitions of children from a high-caries population, in a field setting. The study was conducted in the rainforest of Suriname, South America. ART restorations, made by four Dutch dentists, were evaluated after 6 months, 1, 2, and 3 years. Four hundred seventy-five ART restorations were placed in the primary dentition and 54 in first permanent molars of 194 children (mean age 6.09 ± 0.48 years). Three-year cumulative survivals of single- and two-surface ART restorations in the primary dentition were 43.4 and 12.2%, respectively. Main failure characteristics were gross marginal defects and total or partial losses. Three-year cumulative survival for single-surface ART restorations in the permanent dentition was 29.6%. Main failure characteristics were secondary caries and gross marginal defects. An operator effect was found only for two-surface restorations. The results show extremely low survival rates for single- and two-surface ART restorations in the primary and permanent dentitions. The variable success for ART may initiate further discussion about alternative treatment strategies, especially in those situations where choices have to be made with respect to a well-balanced, cost-effective package of basic oral health care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The concept of minimal invasive dentistry has evolved as a consequence of an increased understanding of caries and the development of adhesive restorative materials [27]. Within this concept, prevention and hard tissue preservation are the primary goals, and dentists are encouraged to prefer a more conservative and biological approach rather than a surgical approach, although the latter is sometimes unavoidable. The atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) technique is part of a minimal invasive approach and, as such, a technique that meets the specific goals mentioned above. In brief, with ART, soft demineralized carious tooth tissue is removed using hand instruments only, followed by restoration of the tooth with an adhesive restorative material, often glass ionomer cement [4, 7]. Because neither electricity nor running water is required for this treatment approach, ART can be applied in almost any setting. Although initially developed to provide restorative dental treatment in outreach or rural areas, ART or modified ART techniques are increasingly introduced into dental clinics in industrialized countries [1, 11, 14].

Since its introduction in the mid-1980s, ART has been evaluated in several community field trials. These studies served mainly to obtain information on technical aspects of the process, handling characteristics of the restorative material, and on the survival of the restorations. They led to improvement of the technique [20] and to the development of new, more appropriate glass ionomer restoration materials, especially for ART purposes.

Studies focussing on the survival of ART restorations have shown that the ART approach is very successful in restoring single-surface dentine lesions in the permanent dentition: 3-year survival rates of 71–92% have been reported [5, 6, 9, 10, 12, 20]. Regarding the survival rates of ART restorations in the primary dentition, only a few field studies were performed. They showed acceptable survival rates (65–96.7%) for single-surface ART restorations, but generally low success rates (31–76.1%) for multi-surface ART restorations, even with the newer glass ionomer materials [2, 3, 11–13, 19, 23, 24, 28]. Although its performance under multisurface conditions is disappointing, ART is considered a valuable approach towards the treatment of dental caries. The use of ART has resulted in the retention of many teeth that would otherwise have been extracted in a later stage. Nevertheless, there still remain some controversies towards the technique, presumably based on the inconsistency in survival results. Moreover, a recent study, investigating the influence of dental treatment on the oral health of a Surinamese child population, concluded that performing ART restorations only, did not contribute significantly to an improvement of the oral health, suggesting that ART alone is not a sufficient solution in the battle against dental decay (van Gemert-Schriks et al., submitted, 2007).

Frencken et al. [8] described comprehensively that ART should be part of a basic package of oral care in which prevention and urgent care are also represented. However, within this package, these three components should be geared to one another as much as possible and the individual effects of all three components must be sufficient and beneficial under different circumstances. When the success of either component, particularly ART, cannot be guaranteed, its contribution in the package should be reduced. Thus, the evaluation of ART in different countries or communities, among different kinds of caries-risk populations and under diverging conditions remains useful. Therefore, the aim of this study is to evaluate the survival of both single- and two-surface ART restorations in the primary and permanent dentitions of children from a high-caries population in a field setting on a longitudinal base.

Materials and methods

This cohort study was conducted in the rainforest of Suriname, South America. It was part of a large-scale project investigating the influence of dental treatment on the oral health of children (van Gemert-Schriks et al., submitted, 2007). Within the scope of that particular project, 380 6-year-old children were divided randomly among four different treatment groups. Material presented in the current article concerns only those children who received restorative treatment, according to the ART method, either in their primary or permanent dentitions.

The restorative treatments were performed in accordance with the ART guidelines [4, 7] and took place in empty classrooms where four children were treated at the same time. Ketac-Molar (3M-ESPE®) was used as the restorative material of choice. The treatments were carried out by four Dutch dentists who were trained in ART during a 1-week ART course and by using ART in children from their own practices, for a period of 3 months, before the start of the treatment phase of the study. They were assisted by six Surinamese health care assistants from the Medical Mission who completed an ART course supplemented with some basic dental knowledge. The dentists were asked to note any contamination with blood and/or saliva during the restoration of the cavity. Furthermore, the presence or absence of adjacent teeth was noted. During the treatment, one of the authors (MGS), who was not involved in the treatment phase, observed and classified the overall behavior of the child, based on a modified Venham scale [23, 29]. Before the study, this observer was trained in using the Venham behavior scale by scoring 42 videotapes of children in a dental situation. These observations were compared to the consensus score of two calibrated observers. This comparison resulted in a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.87, implying an excellent agreement.

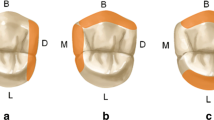

Restorations were not assessed at the time of placement (T0). The children were revisited for evaluation of the ART restorations 6 months (T1), 1 year (T2), 2 years (T3), and 3 years (T4) after the initial treatment. The same author and dentist mentioned above (MGS), evaluated the restorations according to the ART criteria (Table 1) using a CPITN probe, a mouth mirror and a headlamp. Before the study, this person was calibrated against a “gold standard” (Kappa 0.94). This gold standard was achieved by the consensus of two experienced dentists during the assessment of 24 extracted molars with ART restorations. Restorations scored code 00 or 10 were considered successful, codes 11–40 were classified as failures, and codes 50–90 were assigned in case the tooth was unavailable for evaluation. If a tooth or restoration showed multiple defects, a marginal defect dominated an over- or underfilled restoration (10, 11 > 12, 13), secondary caries dominated a marginal defect (20, 21 > 10, 11), absence of a restoration dominated secondary caries (30 > 20, 21), and an overfilled cavity dominated an underfilled cavity (13 > 12).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, version 12.0.1 (SPSS, Chicago, USA). All significant differences were detected at a 95% confidence level.

Kaplan–Meier survival analyses were performed on the censored data of both single- and two-surface restorations. The significance of differences between survival curves was determined with log-rank tests. Possible confounding variables were taken into account using a Cox regression analysis.

Results

As stated in the “Materials and methods” section, the children in this study were derived from a larger study population of children participating in another project. The overall caries prevalence, expressed in terms of decayed, missing and filled surfaces (dmfs) among that group of children, was 11.51 (SD 10.5; range 0–53) in the primary dentition and 0.20 (SD 0.62; range 0–5) in the permanent dentition. According to the standards of the World Health Organisation [17], this denotes a high-caries child population based on the caries prevalence in the primary dentition. Within the larger group, 194 children (mean age 6.09 ± 0.48 years) received ART restorations in either their primary or permanent teeth, or both. Only these children were included in the current study. Their baseline caries prevalence was 12.75 (SD 9.88; range 0–53) in the primary dentition and 0.23 (SD 0.67; range 0–5) in the permanent dentition.

At baseline (T0), 475 ART restorations were placed in the primary dentition (mainly first and second molars) and 54 in the first permanent molars (predominantly mandibular). Table 2 presents data for the ART restorations, performed at baseline. A Mann–Whitney U test showed that children who received two-surface restorations scored higher on the Venham behavior scale (p = 0.005) than children that received single-surface restorations, in the primary dentition. Furthermore, dentists reported more contamination (chi-square = 25.02, df = 1, p < 0.001) when placing two-surface restorations than single-surface restorations.

The lost-to-follow-up percentage of the restorations originally placed was 4.63%. After 3 years, the cumulative survival of the single-surface ART restorations in the primary dentition was 43.4% (standard error (SE) 10.9%). For the two-surface restorations, a cumulative survival of 12.2% (SE 2.99%) was observed. The survival curves, with censored data, are presented in Fig. 1a and b. The cumulative survival of the single-surface ART restorations in the permanent dentition was 29.6% (SE 8.2%) after 3 years (Fig. 2).

Table 3 represents the failure characteristics for the restorations in both primary and permanent dentitions at 3 years. The main failure characteristics of both single- and two-surface ART restorations in the primary dentition were gross marginal defects (score 11) and total or partial losses (score 30). For restorations in the permanent dentition, the main failure characteristics were secondary caries (score 21) and gross marginal defects (score 11).

A log-rank test indicated that there were no statistically significant differences in survival times between the four dentists regarding single-surface restorations in both primary and permanent teeth. However, regarding the two-surface restorations in the primary dentition, statistically significant differences between the four dentists appeared (log-rank statistic 11.7, df = 3, p = 0.009). The separate survival curves are presented in Fig. 3.

To detect any confounding variables on the survival of the ART restorations, a Cox regression analysis was performed. No significant relation could be found, indicating that neither the presence or absence of an adjacent tooth, nor contamination with blood and/or saliva, nor the behavior of the child during the restorative phase of the treatment had an influence on the 3-year survival of the restorations in the primary dentition. No effect also could be found regarding the number of restorations per child.

Neither of these variables had an effect on the survival rates in the permanent dentition, except for the presence of adjacent teeth. Restorations in teeth where no adjacent tooth was present were found to be more likely to fail (hazard ratio = 6.53, 95% CI 2.66–16.02, p < 0.001).

Discussion

In contrast with other studies, the results of this study show extremely low survival rates for both single- and two-surface ART restorations in the primary and permanent dentitions. An operator effect was observed for two-surface restorations only. Neither the behavior of the child during restoration, and the number of restorations per child, nor the contamination of preparations with blood or saliva had a significant influence on the survival of the restorations in this study.

This field study was performed correctly and the statistical power was sufficiently high to detect at least medium effects. However, because it was part of a large-scale randomized controlled clinical trial, no comprehensive criteria were formulated beforehand regarding, for example, the number of restorations per patient, and the location and the size of the cavities. This aspect is inherent to many cohort studies and it does not imply an inferior study quality, but it limits a meaningful comparison with other survival studies.

Although all possible efforts were exercised to trace the participating children over the evaluation period, 22 restorations (4.63%, eight children), all in primary molars, could not be evaluated at any of the recall visits. Either the children did not show up, or the teeth concerned had exfoliated before the first evaluation. These restorations were regarded as missing data and, therefore, excluded from further analysis. Twenty-six restorations (5.47%, 21 children) were “lost” for evaluation because the teeth either exfoliated or the child moved to another district during the course of the study, but after the first evaluation. These restorations (scores 60–90) were treated as censored data and not as true failures because they survived up to a certain moment.

Many causative factors could be suggested that might explain the failure of the ART restorations, such as secondary caries, cervical margin gaps, material properties, and field conditions (outside temperature, atmospheric humidity). However, many other ART studies face these or comparable problems and, therefore, these factors cannot sufficiently explain the extremely low survival rates found in this particular study. The operator difference for the survival rates of the two-surface restorations was not unique, and not a sufficient explanation for the disappointing survival results. Operator effects are often found in ART studies [4, 9, 15, 21, 26] and, as in every profession, there will always be individual differences in technical skills. The finding that the absence of an adjacent tooth was related to a lower 3-year survival of single-surface ART restorations in permanent molars could not be explained. One can only speculate about possible reasons for this relationship, such as that these freestanding molars experience larger occlusal forces.

A possible influence of the relatively high caries prevalence on the survival of the restorations could be hypothesized, but is very doubtful. A study in Indonesia, where the child population exhibited a much higher caries prevalence, also found disappointing survival rates for two-surface ART restorations [28], but these rates were not as extreme as those found in the current study. The survival rates for single-surface ART restorations, derived from other earlier cited studies, were all very promising regardless of the caries profile of the study populations. Furthermore, no effect on the survival rates of the restorations was found when the number of restorations per child was included in the analysis.

The ART protocol prescribes not to eat or drink within at least 1 h after the completion of the restorative treatment [7]. The children in the current study were not supervised after they received restorative treatment and consequently, their food intake could not be controlled. Future studies should take this aspect into account.

Other patient-related factors that may influence the survival of the restorations are the behavior and saliva flow of the child. The survival of the ART restorations in this study was analyzed at the restoration level. This method requires independency of the restoration data and, with respect to the mentioned patient-related possible bias, this assumption could not be guaranteed. To control for this lack of independency, the survival analyses also were performed at the patient level, including only one randomly selected restoration per child. These analyses did not render higher survival rates.

The predominant failure characteristics for both single- and two-surface ART restorations in the primary dentition were gross marginal defects and total or partial losses. This agrees with previous studies concerning the survival of ART restorations in the primary dentition [6, 13, 25, 26]. Gross marginal defects could be induced by occlusal forces or insufficient wear resistance of the restorative material. Ketac-Molar was specifically developed for ART purposes [13], and it has shown excellent results for posterior restorations in the primary dentition [16, 22]. Glass ionomer restorations can be dislodged for a number of reasons, such as insufficient cleaning and conditioning of the cavity, and improper mixing of the material. None of these conditions was recorded at the time the tooth was restored. However, all dentists and chair-side assistants followed the ART guidelines and the manufacturer’s instructions as much as possible under the given circumstances.

The main reasons for failure of the single-surface restorations in the permanent dentition were gross marginal defects and secondary caries. This latter finding is somewhat surprising and contrasts with earlier ART studies [5, 6, 10, 26]. Glass ionomer cement has been the restorative material of choice for the ART technique, based mainly on its fluoride releasing and, thus, caries-preventive properties [7]. Many studies underline these characteristics of glass ionomer [18, 26, 30, 31].

The extremely low survival of the ART restorations observed in this study remains unexplained. Circumstances that were not recognized as possible interfering factors at the start of the study might have played an important role, including cultural and seasonal dietary influences. People living in the rainforest of Suriname eat seasonal fruits such as mangos and fruits of the fiber palm (Awarra). In particular, the latter may influence the survival of the restorations, given the frequency and method in which they are consumed. The authors have seen unusual wear patterns, also in adult dentitions, which might have been caused by excessive consumption of Awarras. A possible causality between these dietary habits and the survival of the ART restorations can only be disclosed by future controlled studies.

Although previous studies have suggested that ART should not be considered as a routine procedure to restore multisurface cavities [13, 24], based on the results of this study, even the ART restoration of single-surface cavities might be reconsidered. This study underlines the inconsistency and variation in the success of the treatment. Apparently, certain conditions must be fulfilled to make ART successful. These conditions can be approached, but not always achieved, under all circumstances.

Conclusion

The uncertain predictability for the success of ART may introduce further discussion about alternative treatment strategies, especially in those situations where choices have to be made with respect to a well-balanced, cost-effective package of basic oral health care. To gain insight into factors determining the cumulative success rate of ART restorations, future studies should focus in more detail on variables that could possibly contribute to the failure of restorations.

References

Burke FJT, McHugh S, Shaw L, Hosey MT, Macpherson L, Delargy S, Dopheide B (2005) UK dentists’attitudes and behavior towards Atraumatic Restorative Treatment for primary teeth. Br Dent J 199:365–369

Ersin NK, Candan U, Aykut A, Oncaq O, Eronat C, Kose T (2006) A clinical evaluation of resin-based composite and glass-ionomer cement restorations placed in primary teeth using the ART approach: results at 24 months. J Am Dent Assoc 137:1529–1536

Frencken JE, Songpaisan Y, Phantumvanit P, Pilot T (1994) An atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) technique: evaluation after two years. J Dent Res 73:1014 (abstract 24)

Frencken JE, Pilot T, Songpaisan Y, Phantumvanit P (1996) Atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) rationale, technique and development. J Public Health Dent 56:135–140

Frencken JE, Makoni F, Sithol W (1998) ART restorations and glass-ionomer sealants in Zimbabwe: survival after 3 years. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 26:372–381

Frencken JE, Makoni F, Sithol W, Hackenitz E (1998) Three-year survival of one-surface ART restorations and glass-ionomer sealants in Zimbabwe. Caries Res 32:119–126

Frencken JE, Holmgren CJ (1999) Atraumatic Restorative Treatment for dental caries. STI book b.v., Nijmegen pp 18–26, 41–51

Frencken JE, Holmgren CJ, van Palenstein Helderman WH (2002) Basic Package of Oral Care. WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Care Planning and Future Scenarios, Nijmegen

Frencken JE, van ‘t Hof MA, van Amerongen WE, Holmgren CJ (2004) Effectiveness of Single-surface ART restorations in the permanent dentition: a meta-analysis. J Dent Res 83:120–123

Holmgren CE, Lo ECM, Hu DY, Wan HC (2000) ART restorations and sealants placed in Chinese schoolchildren—results after three years. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 28:314–320

Honkala E, Behbehani J, Inbricevic H, Kerosuo E, Al-Jame G (2003) The atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) approach to restoring primary teeth in a standard dental clinic. Int J Paediatr Dent 13:172–179

Lo ECM, Luo Y, Fan MW, Wei SHY (2001) Clinical investigation of two glass-ionomer restoratives used with the atraumatic restorative treatment approach in China: two-year results. Caries Res 35:458–563

Lo ECM, Holmgren CJ (2001) Provision of atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) restorations to Chinese pre-school children—a 30-month evaluation. Int J Paediatr Dent 11:3–10

Louw AJ, Sarvan I, Chikte UM, Honkala E (2002) One-year evaluation of atraumatic restorative treatment and minimal intervention techniques on primary teeth. S Afr Dent J 57:366–371

Mallow PK, Durward CS, Klaipo M (1998) Restoration of permanent teeth in young rural children in Cambodia using the atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) technique and Fuji II glass-ionomer cement. Int J Paediatr Dent 8:35–40

Marks LAM, van Amerongen WE, Borgmeijer PJ, Groen HJ, Martens LC (2000) Ketac Molar versus Dyract class-II restorations in primary molars: twelve month clinical results. J Dent Child 37–41

Marthaler TM, Møller IJ, von de Fehr FR (1990) Symposium report: caries status in Europe and predictions of future trends. Caries Res 24:381–396

McComb D, Erickson RL, Maxymiw WG, Wood RE (2002) A clinical comparison of glass ionomer, resin modified glass ionomer and resin composite restorations in the treatment of cervical caries in xerostomic head and neck radiation patients. Oper Dent 27:430–437

Phantumvanit P, Songpaisan Y, Frencken JE, Pilot T (1994) Atraumatic Restorative Treatment (ART) technique: an evaluation after 1 year. Int Dent J 44:460–464

Phantumvanit P, Songpaisan Y, Pilot P, Frencken JE (1996) Atraumatic restorative treatment (ART): a three-year community field trial in Thailand—survival of one-surface restorations in the permanent dentition. J Public Health Dent 56:141–145

Rahimtoola S, van Amerongen E (2002) Comparison of two tooth saving preparation techniques for one surface cavities. J Dent Child 69:16–26

Rutar J, McAllan L, Tyas MJ (2002) Three-year clinical performance of glass-ionomer cement in primary molars. Int J Paediatr Dent 12:146–147

Schriks MCM, van Amerongen WE (2003) Atraumatic perspectives of ART: psychological and physiological aspects of treatment with and without rotary instruments. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 31:15–20

Smales RJ, Yip HK (2000) The atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) approach for primary teeth: review of the literature. Pediatr Dent 22:294–298

Taifour D, Frencken JE, Beiruti N, van’t Hof MA, Truin GJ (2002) Effectiveness of glass-ionomer (ART) and amalgam restorations in the deciduous dentition: results after 3 years. Caries Res 36:437–444

Taifour D, Frencken JE, van ’t Hof MA, Beiruti N, Truin GJ (2003) Effects of glass-ionomer sealants in newly erupted first molars after 5 years: a pilot study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 31:314–319

Tyas MJ, Anusavice KJ, Frencken JO (2000) Minimal intervention dentistry—a review. FDI Commission Project 1–97. Int Dent J 50:1–12

van den Dungen GM, Huddleston Slater AE, van Amerongen WE (2004) ART or conventional restorations? A final examination of proximal restorations in deciduous molars. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd 111:345–349

Venham LL, Bengston D, Cipes M (1977) Children’s response to sequential dental visits. J Dent Res 56:454–459

Wiegand A, Buchalla W, Attin T (2007) Review on fluoride-releasing restorative materials—fluoride release and uptake characteristics, antibacterial activity and influence on caries formation. Dent Mater 23(3):343–362

Xu X, Burgess JO (2003) Compressive strength, fluoride release and recharge of fluoride-releasing materials. Biomaterials 24:2451–2461

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Netherlands Institute of Dental Sciences (IOT), the Netherlands Foundation for the advancement of Tropical Research (WOTRO), the Foundation “De Drie Lichten” in The Netherlands and 3M -ESPE. The authors would like to thank the Director of the Surinamese Ministry of Health and the Medical Mission of Suriname for their intensive and enthusiastic cooperation, their inspiring input, and the provision of all facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Gemert-Schriks, M.C.M., van Amerongen, W.E., ten Cate, J.M. et al. Three-year survival of single- and two-surface ART restorations in a high-caries child population. Clin Oral Invest 11, 337–343 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-007-0138-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-007-0138-8