Abstract

Background

The Quick Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (QuickDASH) questionnaire is a region-specific, self-administered questionnaire, which consists of a disability/symptom (QuickDASH-DS) scale, and the same two optional modules, the work (DASH-W) and the sport/music (DASH-SM) modules, as the DASH. After the Japanese version of DASH (DASH-JSSH) was cross-culturally adapted and developed, we made the Japanese version of QuickDASH (QuickDASH-JSSH) by extracting 11 out of 30 items of the DASH-JSSH regarding disability/symptoms. The purpose of this study was to test the reliability, validity, and responsiveness of QuickDASH-JSSH.

Methods

A series of 72 patients with upper extremity disorders completed the QuickDASH-JSSH, the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), and the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain. Thirty-eight of the patients were reassessed for test–retest reliability 1 or 2 weeks later. Reliability was investigated by the reproducibility and internal consistency. To analyze the validity, a principal component analysis and the correlation coefficients between the QuickDASH-JSSH and the SF-36 were obtained. The responsiveness was examined by calculating the standardized response mean (SRM; mean change/SD) and effect size (mean change/SD of baseline value) after carpal tunnel release of the 17 patients with carpal tunnel syndrome.

Results

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in the QuickDASH-DS was 0.88. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the same was 0.82. The unidimensionality of the QuickDASH-DS was confirmed. The correlation coefficients between the QuickDASH-DS and the DASH-DS, DASH-W, or the DASH-SM were 0.92, 0.81, or 0.76, respectively. The correlation coefficients between the QuickDASH-DS score and the subscales of the SF-36 ranged from −0.29 to −0.73. The correlation coefficient between the QuickDASH-DS score and the VAS for pain was 0.52. The SRM/effect size of QuickDASH-DS was −0.54/−0.37, which indicated moderate sensitivity.

Conclusion

The Japanese version of QuickDASH has equivalent evaluation capacities to the original QuickDASH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health measurement scales are important patient outcome tools to measure health status and evaluate medical intervention.1 Recently several measures for the evaluation of upper extremity function have been developed.2–7 Most of them are joint-specific2,3 or diseasespecific.4,5 Others are intended to evaluate the function of the entire upper extremity using a region-specific measure.6,7 The Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire was devised as a regionspecific measure by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) in collaboration with a number of other organizations.7 The rationale for use of this measure is that the upper extremity is a functional unit or kinetic chain.8 Therefore, the DASH is suitable for measuring health status outcome because it is mainly a measure of disability. The DASH is now available in several languages and in use in several countries.9–16 Studies of reliability and validity have been published for not only the original version,17 but also for the Japanese9 and other language versions.10–16

The QuickDASH was developed as a shortened version of the DASH Outcome Measure.18 Instead of the 30 items of the DASH Outcome Measure, the QuickDASH uses 11 items to measure physical function and symptoms in people with any or multiple musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb. Like the DASH Outcome Measure, the QuickDASH also has two optional modules intended to measure symptoms and function in athletes, performing artists, and other workers whose jobs require a high degree of physical performance.

We, the Impairment Evaluation Committee (Japanese Society for Surgery of the Hand), have completed cross-cultural adaptation and development of the DASH Japanese version (DASH-JSSH) and reported its reliability, validity, and responsiveness.9 After the QuickDASH was released, we also developed the QuickDASH Japanese version (QuickDASH-JSSH). The purpose of this study was to test the reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the QuickDASH-JSSH, to compare them with those of the full DASH-JSSH, and to make the QuickDASH-JSSH available for use in Japan.

Materials and methods

In accordance with published guidelines,19,20 we organized the DASH-JSSH committee consisting of translators, researchers, a methodologist, and a Japanese language expert, and culturally adapted the full DASH (version 2.0) into Japanese.9

After the QuickDASH was released by the AAOS, we, the Impairment Evaluation Committee (Japanese Society for Surgery of the Hand), extracted 11 items from the 30 items of the full DASH and adopted two optional modules of the full DASH to develop the QuickDASH Japanese version (QuickDASH-JSSH). The QuickDASH-JSSH version was then evaluated with regard to reliability, validity, and responsiveness.

The QuickDASH questionnaire

The main part of the QuickDASH is an 11-item disability/ symptom (QuickDASH-DS) scale concerning the patient’s upper extremity.18 Each item has five response choices, ranging from “no difficulty or no symptom” to “unable to perform activity or very severe symptom,” and is scored on a one-to-five scale. The items ask about the severity of each of the symptoms of pain, activityrelated pain, tingling, weakness, and stiffness (two items: numbers 9,10), the degree of difficulty in performing various physical activities because of an arm, shoulder, or hand problem (6 items: numbers 1–6), the effect of the upper extremity problem on social activities, work, and sleep (three items: numbers 7, 8, 11). The psychological effect on self-image (one item: number 30) in the full DASH was excluded in this QuickDASH. These 11 items provide the DASH disability/symptom (DASH-DS) score ranging from zero (no disability) to 100 (the severest disability), after summation of the scores from all items and transformation.

The QuickDASH, as does the full DASH, contains two optional modules concerning the ability to work, and the ability to perform sports and/or to play musical instruments. These two optional modules each consist of four items, each of which has a one-to-five scale. These provide the DASH work (DASH-W) score and the DASH sport/music (DASH-SM) score ranging from zero (no disability) to 100 (the severest disability), after summation of the scores from all items and transformation.

Patients and setting

A series of 73 patients with upper extremity disorders was seen on an outpatient basis in five orthopedic surgery departments in Japan.9 Exclusion criteria were age below 18 years, and relevant comorbidity (e.g., connective tissue disease). One patient with comorbidity of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) was excluded. The study was conducted on a total of 72 patients (17 men, 55 women) with carpal tunnel syndrome (38 patients), rotator cuff disease (10 patients), cubital tunnel syndrome (7 patients), thoracic outlet syndrome (4 patients), or others (13 patients). The mean age was 54.1 years (SD 14.9 years, range 20–81 years). After informed consent was obtained from the patients to participate in this study, they answered the DASH-JSSH questionnaire, the official Japanese version of the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36; version 1.2),21,22 and the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [0–10 scale] for pain. The data collected from the 72 patients were used as a baseline value. Among the 72 patients, the 38 who had no treatment such as medication and rehabilitation during the consecutive visits were readministered the DASH-JSSH questionnaire and VAS for pain 1 or 2 weeks later. The 17 patients with carpal tunnel syndrome who received carpal tunnel release by three hand surgeons answered the DASH-JSSH questionnaire and VAS for pain twice preoperatively and postoperatively (3 months after surgery). The protocol of this study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board prior to implementation.

Assessment of reliability, validity, and responsiveness

Reliability was investigated by looking at the reproducibility and internal consistency based on the test-retest method. The following analyses were conducted to examine the validity. A principal component analysis was conducted to examine the construct validity and the unidimensionality of the QuickDASH-JSSH disability/symptom (QuickDASH-JSSH-DS). Completeness of item responses of the QuickDASH-JSSH and VAS for pain was examined. Correlation coefficients between the QuickDASH-JSSH and the SF-36 were obtained, and the following hypotheses were examined to investigate concurrent validity: (1) “physical functioning” (SF-36-PF) or “role-physical” (SF-36-RP) would exhibit the strongest association; (2) “bodily pain” (SF-36-BP) would exhibit the next strongest association; and (3) “mental health” (SF-36-MH) and “vitality” (SF-36-VT) would exhibit the weakest association. Correlation coefficients between the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS and the full DASH-JSSH-DS, the DASH-JSSH-W, or the DASH-JSSH-SM scales were also obtained.

Correlation coefficients between the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS and the SF-36 were obtained. Correlation coefficients between the QuickDASH-JSSH and VAS for pain were obtained, and the criterion-based validity investigation looked at the following hypothesis: the correlation between the QuickDASH-JSSH and VAS for pain would be high. The responsiveness was examined by calculating the standardized response mean (SRM; mean change/SD)23 and effect size (mean change/SD of baseline value)24 after carpal tunnel release of the patients with carpal tunnel syndrome.

Statistical analysis

Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Lilliefors probability tests were used to assess distribution of the QuickDASH-JSSH and ages of the subjects. The interval measurement of QuickDASH-JSSH-DS was not normally distributed. Therefore, correlations between QuickDASH-JSSH-DS and other instrument scales were assessed using a nonparametric test (Spearman’s correlation). Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess internal consistency. Instrument test-retest reliability was assessed with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 12.0 J software. The critical values for significance were set at P < 0.05.

Results

Completeness of item responses

No patients had difficulty completing the DASH-JSSH questionnaire.9 Most of the patients considered all the items of the DASH-JSSH-DS section to be clear. Two out of the 72 patients (nonrespondent group) did not answer one item of the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS. One patient did not respond to item 5. The other patient did not respond to item 7. Fifty-five out of 72 (76%) patients answered the DASH-JSSH-W. However, only 15 out of 72 (21%) patients responded to the DASH-JSSH-SM.9

The mean, median, and standard deviation of the QuickDASH-JSSH scores were 28, 24, and 21, respectively. The numbers of ceiling and floor scores of the QuickDASH-JSSH were identified. One patient had a maximum disability score of 100 (floor) on the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS. Three and four patients had the minimum disability score of zero (ceiling) on the DASH-JSSH-W and the DASH-JSSH-SM, respectively.9

Reliability

Internal consistency was assessed by use of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The alpha coefficient for the 11 items in the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS was high (0.88). When the alpha coefficient was calculated for each of the 11 items by eliminating each item, one by one, the range was 0.87–0.88, and no items were found to change the internal consistency substantially.

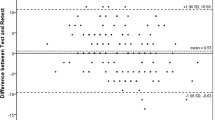

Instrument test-retest reliability was assessed with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). There were 38 patients for the test-retest reliability, and the period between the first and second tests was a mean of 9.2 days (range 6–17 days). The ICC for the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS was 0.82 (95% confidence interval: 0.69–0.90). All ICCs for the QuickDASH-JSSH indicated sufficient reproducibility.

Validity

A principal component analysis was conducted to confirm the unidimensionality of the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS. The first factor had an eigenvalue (amount of variation in the total sample accounted for by that factor)14 of 5.12, which explained the 47% total variance of the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS scores of the patients (Fig. 1). The unidimensionality was found to be strong as a result of a substantial difference between the first and the second factors (eigenvalue 1.74, Fig. 1). When looking at the first factor loading for each item, all items had loading (the correlation with the total score) of 0.4 or higher (Table 1) and communalities of more than 0.4.

The correlation coefficients between the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS and the DASH-JSSH-DS, DASH-JSSH-W, or the DASH-JSSH-SM were 0.92, 0.81, and 0.76, respectively (Table 2, P < 0.01). These results indicate strong correlations between the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS and the DASH-JSSH-DS, between the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS and the DASH-JSSH-W, and between the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS and the DASH-JSSH-SM.

The correlations between the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS score and the subscales of the SF-36 scale ranged from −0.29 to −0.73 (Table 2). The strongest correlation was observed in “role-physical,” followed by “physical functioning” and “bodily pain”. The correlation between QuickDASH-JSSH-DS and “mental health” or “vitality” was somewhat weak. These results support the hypothesis set down in advance, except the strongest correlation (Table 2).

No statistical difference (P = 0.161) in age was found between men (mean [SD], 50 [4.9] years old) and women (mean [SD], 55 [1.8] years old). The QuickDASH-JSSH-DS scores between men (mean score: 21.1) and women (mean score: 30.6) was compared by Mann-Whitney U-test. There was no statistical difference between them (P = 0.09). This result supports our hypothesis. The correlation between the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS score and age was weak (r = 0.280, P < 0.05).

The correlation between the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS score and the degree of pain was examined and observed as moderate for the SF-36 bodily pain score and the VAS for pain (Table 2).

Responsiveness

Seventeen of 38 patients with carpal tunnel syndrome received carpal tunnel release. They completed the QuickDASH-JSSH at 3 months after the surgery. The mean subject age was 57 years (SD: 10 years, range: 48–78 years). There were 16 women and one man. The differences between preoperative and postoperative QuickDASH-JSSH-DS scores were not normally distributed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Lilliefors probability tests. Calculated SRM and effect size of QuickDASH-JSSH-DS was −0.54/−0.37. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test was used to analyze QuickDASH-JSSH-DS over time. There was a statistical difference between the median value of preoperative and postoperative QuickDASH-DS scores (P = 0.028, one-tailed).

Discussion

Japanese adaptation of the DASH questionnaire was performed following a systematic standardized approach.19,20 The purpose of this study was to examine the psychometric qualities of the QuickDASH-JSSH by assessing its psychometric standards in the area of the reliability, validity, and responsiveness.

The QuickDASH-JSSH consists of an 11-item scale and two optional 4-item scale modules. It took patients a similar amount of time to complete the full DASH-JSSH compared with the time to complete the other language versions.11 This may indicate that it will take them a shorter time to complete the QuickDASH questionnaire. In the full DASH, the elderly patients left no more than three items unanswered, and those were thought to pertain to specific activities, such as sexual activities and recreational activities, that those individuals do not perform.9 In the QuickDASH such activities, especially sexual activities from the full DASH, were eliminated. That may explain why all patients except two completed the QuickDASH. We can take advantage of the QuickDASH instead of the full DASH especially in the case of epidemiological studies in the workplace or when measuring the health status of elderly people. The lack of ceiling effects assure the authors of the validity of this version of the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS.

As for measurement precision, recommended reliability standards for individual-level applications range from a low of 0.90 to a high of 0.95, which is the desired standard.25 Most general health status measures (e.g., SF-36, the Nottingham Health Profile [NHP], the Functional status questionnaire [FSQ]),25 as well as lesion- or joint-specific questionnaires (e.g., the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire26 and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index [WOMAC]27), cannot meet this standard, whether they are designed for individual-patient applications or group-level applications. Most translated DASH versions10,12–15 as well as the original full DASH17 had internal consistency higher than 0.95. Beaton et al. reported that the QuickDASH had internal consistency of 0.94 so that QuickDASH has the potential to work well in the monitoring care of individual patients in clinical settings;18 but the QuickDASH-JSSH had internal consistency of 0.88. We may say that QuickDASH-JSSH could be used with caution for daily assessment of individual patient status. But as is stated in the DASH homepage (http://www.dash.iwh.on.ca/), because the full questionnaire provides greater precision, it may be the best choice for clinicians who wish to monitor arm pain and function in individual patients. We would prefer that the QuickDASH be used for groups of workers or patients.

The validation process of the QuickDASH-JSSH questionnaire has shown that it has a similar validity to the other language versions10,12–16 including the original full DASH.17 The strong correlations between the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS and SF-36 subscales (role of physical health, physical functioning, and bodily pain) support this validity and demonstrate similar results to the validation papers for the other language versions including the original full DASH. These results demonstrated that the QuickDASH-JSSH measures the important elements that make up health-related quality of life (QOL).

The QuickDASH-JSSH-DS scale exhibited high unidimensionality and there was no low item-scale correlation. The communalities of this scale were very high. These results show that the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS has a high quality of validation.

Cohen’s rule-of -thumb for interpreting the “effect size index,” i.e., a value of 0.2 is small, 0.5 is moderate, and 0.8 or greater is large, can be applied to the SRM.23 The responsiveness of the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS for patients with carpal tunnel syndrome was moderate 3 months after carpal tunnel release operation, although other studies showed higher responsiveness of DASHDS than our results.28 There was a statistical difference between the mean value of preoperative and postoperative QuickDASH-JSSH-DS scores.

We believe the strengths of this study are that the QuickDASH-JSSH-DS scale demonstrated good reproducibility, consistency, and validity. Moreover, it had a moderate responsiveness.

A limitation of this study is that we cannot successfully demonstrate the responsiveness of QuickDASH because the sample size was relatively small and the patients’ response rate was low. Moreover, the samples of this study are not representative of the general population.

Conclusions

We can conclude that the Japanese version of the QuickDASH has equivalent evaluation capacities to the original QuickDASH. We expect that the use of this scale in Japan to assess treatment by the patients themselves will contribute to meaningful improvement of outcome for patients with upper extremity disorders. Above all, the QuickDASH could be used for groups of patients.

References

J Dawson A Carr (2001) ArticleTitleOutcomes evaluation in orthopaedics J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 83 313–5 10.1302/0301-620X.83B3.12148 Occurrence Handle10.1302/0301-620X.83B3.12148 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3MzgvFKhtg%3D%3D

CR Constant AHG Murley (1987) ArticleTitleA clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder Clin Orthop 214 160–4 Occurrence Handle3791738

InstitutionalAuthorNameResearch Committee, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons RR Richards KN An LU Bigliani RJ Friedman GM Gartsman AG Gristina et al. (1994) ArticleTitleA standardized method for the assessment of shoulder function J Shoulder Elbow Surg 3 347–52 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80019-0 Occurrence Handle10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80019-0

A Kirkley S Griffin H McLintock L Ng (1998) ArticleTitleThe development and evaluation of a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool for shoulder instability. The Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI) Am J Sports Med 26 764–72 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1M%2FmslOlsA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle9850776

DW Levine BP Simmons MJ Koris LH Daltroy GG Hohl AH Fossel et al. (1993) ArticleTitleA self-administered questionnaire for the assessment of severity of symptoms and functional status in carpal tunnel syndrome J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 75 1585–92 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2c%2FmsVOjsg%3D%3D

DP Martin R Engelberg J Agel MF Swiontkowski (1997) ArticleTitleComparison of the Musculoskeletal Function Assessment Questionnaire with the Short Form 36, the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index, and the Sickness Impact Profile Health-Status Measures J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 79 1323–35 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2svlvVSmsg%3D%3D

PL Hudak PC Amadio C Bombardier InstitutionalAuthorNamethe Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG) (1996) ArticleTitleDevelopment of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected] Am J Ind Med 29 602–8 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L Occurrence Handle10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK28zmvFOrsg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle8773720

AM Davis DE Beaton P Hudak P Amadio C Bombardier D Cole et al. (1999) ArticleTitleMeasuring disability of the upper extremity: a rationale supporting the use of a regional outcome measure J Hand Ther 12 269–74 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3c%2FosF2jtg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10622192

T Imaeda S Toh Y Nakao J Nishida H Hirata M Ijichi et al. (2005) ArticleTitlefor the Impairment Evaluation Committee, Japanese Society for Surgery of the Hand. Validation of the Japanese Society for Surgery of the Hand Version of the Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH-JSSH) Questionnaire J Orthop Sci 10 353–9 10.1007/s00776-005-0917-5 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00776-005-0917-5 Occurrence Handle16075166

I Atroshi C Gummesson B Andersson E Dahlgren A Johansson (2000) ArticleTitleThe disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) outcome questionnaire: reliability and validity of the Swedish version evaluated in 176 patients Acta Orthop Scand 71 613–8 10.1080/000164700317362262 Occurrence Handle10.1080/000164700317362262 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M%2Fos1Glsw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle11145390

T Dubert P Voche C Dumontier A Dinh (2001) ArticleTitleLe questionnaire DASH. Adaptation française d’un outil d’évaluation international (in French) Chir Main 20 294–302 10.1016/S1297-3203(01)00049-X Occurrence Handle10.1016/S1297-3203(01)00049-X Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3MrjsFCqsQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle11582907

M Offenbaecher T Ewert O Sangha G Stucki (2002) ArticleTitleValidation of a German version of the Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand questionnaire (DASH-G) J Rheumatol 29 401–2 Occurrence Handle11838867

RS Rosales EB Delgado ID De La Lastra-Bosch (2002) ArticleTitleEvaluation of the Spanish version of the DASH and Carpal Tunnel Syndrome health-related quality-of-life instruments: cross-cultural adaptation process and reliability J Hand Surg [Am] 27 334–43 10.1053/jhsu.2002.30059 Occurrence Handle10.1053/jhsu.2002.30059

MM Veehof EJA Sleegers NHMJ van Veldhoven AH Schuurman NLU Van Meeteren (2002) ArticleTitlePsychometric qualities of the Dutch language version of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand questionnaire (DASH-DLV) J Hand Ther 15 347–54 Occurrence Handle12449349 Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0894-1130(02)80006-0

R Padua L Padua E Ceccarelli E Romanini G Zanoli PC Amadio et al. (2003) ArticleTitleItalian version of the Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation J Hand Surg [Br] 28 179–86 10.1016/S0266-7681(02)00303-0 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3s3jt1antw%3D%3D

EWC Lee JSY Lau MMH Chung APS Li SK Lo (2004) ArticleTitleEvaluation of the Chinese version of the Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH-HKPWH): cross-cultural adaptation process, internal consistency and reliability study J Hand Ther 17 417–23 Occurrence Handle15538683

DE Beaton JN Katz AH Fossel JG Wright V Tarasuk (2001) ArticleTitleMeasuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity J Hand Ther 14 128–46 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M3psFOrsQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle11382253

DE Beaton JG Wright JN Katz InstitutionalAuthorNameUpper Extremity Collaborative Group (2005) ArticleTitleDevelopment of the QuickDASH: comparison of the three item-reduction approaches J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 87 1038–46 10.2106/JBJS.D.02060 Occurrence Handle10.2106/JBJS.D.02060

DE Beaton C Bombardier F Guillemin MB Ferraz (2000) ArticleTitleGuidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures Spine 25 3186–91 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014 Occurrence Handle10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M7jt1Cmug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle11124735

F Guillemin C Bombardier D Beaton (1993) ArticleTitleCross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines J Clin Epidemiol 46 1417–32 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-N Occurrence Handle10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-N Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2c%2Foslalsg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle8263569

S Fukuhara S Bito J Green A Hsiao K Kurokawa (1998) ArticleTitleTranslation, adaptation, and validation of the SF-36 health survey for use in Japan J Clin Epidemiol 51 1037–44 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00095-X Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00095-X Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1M%2Fjt1Sisw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle9817121

S Fukuhara JE Ware SuffixJr M Kosinski S Wada B Gandek (1998) ArticleTitlePsychometric and clinical tests of validity of the Japanese SF-36 health survey J Clin Epidemiol 51 1045–53 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00096-1 Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00096-1 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1M%2Fjt1SisA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle9817122

MH Liang AH Fossel MG Larson (1990) ArticleTitleComparisons of five health status instruments for orthopedic evaluation Med Care 28 632–42 Occurrence Handle10.1097/00005650-199007000-00008 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK3czgvFCgsg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle2366602

LE Kazis JJ Anderson RF Meenan (1989) ArticleTitleEffect sizes for interpreting changes in health status Med Care 27 IssueIDsuppl S178–89 Occurrence Handle10.1097/00005650-198903001-00015 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL1M7lvVehsw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle2646488

CA McHorney AR Tarlov (1995) ArticleTitleIndividual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res 4 293–307 10.1007/BF01593882 Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF01593882 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK28%2FksFamsw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle7550178

Y Suzukamo S Fukuhara S Kikuchi S Konno M Roland Y Iwamoto et al. (2003) ArticleTitleCommittee on Science Project, Japanese Orthopaedic Association. Validation of the Japanese version of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire J Orthop Sci 8 543–8 10.1007/s00776-003-0679-x Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00776-003-0679-x Occurrence Handle12898308

H Hashimoto T Hanyu CB Sledge EA Lingard (2003) ArticleTitleValidation of a Japanese patient-derived outcome scale for assessing total knee arthroplasty: comparison with Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) J Orthop Sci 8 288–93 10.1007/s10776-002-0629-0 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s10776-002-0629-0 Occurrence Handle12768467

RE Gay PC Amadio JC Johnson (2003) ArticleTitleComparative responsiveness of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand, the carpal tunnel questionnaire, and the SF-36 to clinical change after carpal tunnel release J Hand Surg [Am] 28 250–4 10.1053/jhsu.2003.50043 Occurrence Handle10.1053/jhsu.2003.50043

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Imaeda, T., Toh, S., Wada, T. et al. Validation of the Japanese Society for Surgery of the Hand Version of the Quick Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (QuickDASH-JSSH) questionnaire. J Orthop Sci 11, 248–253 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00776-006-1013-1

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00776-006-1013-1