Abstract

The aim of this systematic review is to appraise existing literature on the effects of treatments for antenatal depression on the neurodevelopment outcomes of the offspring. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify studies on different kinds of treatments for antenatal depression (antidepressants and alternative therapies) and their effects on infants’ neurodevelopment. After reading the title, abstract, or full text and applying exclusion criteria, a total of 22 papers were selected. Nineteen papers studied the effects of antidepressant drugs, one on docosahexanoic acid (DHA) (fish oil capsules) and two on massage therapy; however, no studies used a randomized controlled design, and in most studies, the control group comprise healthy women not exposed to depression. Comparisons between newborns exposed to antidepressants in utero with those not exposed showed significant differences in a wide range of neurobehavioral outcomes, although in many cases, these symptoms were transient. Two studies found a slight delay in psychomotor development, and one study found a delay in mental development. Alternative therapies may have some benefits on neurodevelopmental outcomes. Our review suggests that antidepressant treatment may be associated with some neurodevelopmental changes, but we cannot exclude that some of these effects may be due to depression per se.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pregnancy is a sensitive period for a woman’s health, both physical and psychological. It is the time when a new life forms in her body and many hormonal variations take place which can affect mood (Ahokas et al. 2005). In the last two decades, research into the well-being of women around childbirth has increasingly focused on depression in the antenatal rather than in the postnatal period. Studies from different countries have estimated the prevalence of antenatal depression to range from 6 to 38 %. Different studies have found that compared to non-pregnant women, pregnant women at any gestational age have an increased chance of suffering from a mood disorder such as major or minor depression (Dietz et al. 2007; Marchesi et al. 2009; Marcus 2009). Antenatal depression has often been found to be more frequent than postnatal depression, in some cases the estimate being twice that of depression following birth (Field 2011). Moreover, women suffering from antenatal depression are at high risk of developing depression in the postnatal period (Leigh and Milgrom 2008; Marino et al. 2012). According to a number of studies, the highest risk periods for developing a mood disorder are the first and last trimester of pregnancy (Gavin et al. 2005; Field 2011; Marchesi et al. 2009).

Numerous studies and a recent meta-analysis have shown that depression throughout pregnancy may lead to complications (preeclampsia, spontaneous miscarriage) and poor outcomes for the offspring, such a slow intrauterine growth, placental abnormalities, low birth weight, preterm birth, and frequent admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (Bonari et al. 2004; Deave et al. 2008; Field et al. 2006; Grote et al. 2010). Neonates of depressed mothers perform poorly on many clusters of the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS) such as orientation, reflex, excitability, and withdrawal; they are also more aroused and less attentive (Hernandez-Reif et al. 2006; Hollins 2007; Lundy et al. 1999a). Deave et al. (2008) investigated the long-term effects of perinatal depression on child development, and they found that some of the effects on child development previously believed to be associated with postnatal depression were instead associated with depressive symptoms during pregnancy.

Taking these findings into account, it is important to identify and treat all pregnant women who experience symptoms of low mood or severe depression in order to reduce adverse child outcomes. It is not easy for clinicians and mothers to make decisions about the type of therapy that is appropriate for each individual pregnant woman. Many factors such as the severity of the mother’s disease, the consequences of her illness on the developing fetus, and the long-term outcome for both mother and baby need to be considered. Guidelines have been developed to help clinicians decide with their patients the best form of treatment, giving them adequate information to give informed consent to the therapy. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence clinical guideline underlines that drugs should be prescribed cautiously for women who are planning a pregnancy and for those who are pregnant or breastfeeding. They suggest different therapies based on the severity of disease: subthreshold, mild, moderate, severe, and treatment-resistant depression (NICE clinical guideline 45Antenatal and postnatal mental health Clinical management and service guidanceIssued: February 2007). Wisner et al. (2000) introduced five domains: intrauterine fetal death, physical malformations, growth impairment, behavioral teratogenicity, and neonatal toxicity in her decision-making model to ensure that patients and psychiatrists deal with all the critical risk-benefit aspects. Koren et al. (Koren and Nordeng 2012) in his recent review also emphasized that very little has been done to integrate the potential risks, if they exist, and to allow an evidence-based benefit-risk ratio. Good algorithms to evaluate and manage the risk of exposure to depression or antidepressant were made by the American Psychiatric Association in collaboration with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (Yonkers et al. 2009).

Despite these documents helping clinicians and patients make appropriate decisions, pregnant women were found to be diffident toward taking antidepressant drugs, with a high percentage of women discontinuing their use, compared to the use of other therapies such as the counseling service provided by the Motherisk Program (Bonari et al. 2005). This reluctance by pregnant women to take antidepressant drugs should lead clinicians to discuss with their patients the use of psychological interventions or alternative forms of treatments such as light therapy, massage therapy, or omega-3 fatty acid supplementation (Dennis et al. 2007; Dennis and Allen 2010). Currently, the most studied category of treatments is antidepressant use and its effects on the mothers and babies. There is some evidence to show that therapies other than drugs are effective forms of treatment for the mother’s mental illness, but to our knowledge, there are no recent systematic reports on the their impact of antidepressant treatment on the newborn focusing on neurodevelopment (Chaudron 2013; Gentile and Galbally 2011; Lattimore et al. 2005), rather than poor neonatal adaptation syndrome or similar reaction at births (Grigoriadis et al. 2013). The aim of this study is to review existing literature on the neurodevelopmental outcome of newborns born to mothers who were treated for antenatal depression with drugs or alternative therapies. Alternative therapies could have a number of beneficial effects on the offspring through direct nutritional effects or by improving symptoms and well-being in the mothers, but, especially considering their widespread use, it is important to identify any potential negative consequences.

Materials and methods

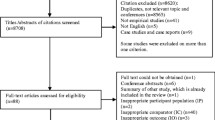

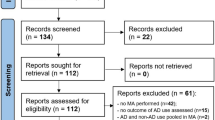

The words “antenatal or postnatal or antepartum or postpartum or peripartum or prepartum or perinatal or pregnancy or neonatal” and “depression” and “treatment or NBAS or Bayley or neurodevelopment or baby outcome” were searched from 1950 to May 2013 in the PubMed, The Cochrane Library, Scopus, Embase, OvidSP, PsychInfo, and ISI Web of Knowledge. The resultant papers were cross-referenced for other relevant studies not identified in the initial research. An extensive manual research of literature was also done by checking pertinent journal and authors. The only studies selected were ones that assessed pregnant women with depression who were treated with drugs or alternative therapies, and where their newborns were measured specifically by using standardized tests of neurodevelopmental outcomes administered by trained staff. Other papers where symptoms are described based on questionnaire or clinical notes were not included. The tests used for neurobehavioral assessment of the infant were NBAS (Brazelton 1973) and NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS) (Lester and Tronick 2004). The same methodology was used for the selection of studies that assessed neurodevelopment and long-term effects on infants. The tests used were the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) second and third editions (Bayley 1993, 2005), the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence third edition (WPPSI) (Wechsler 2002), the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Wechsler 1981, 1999), the BOEL test (Junker et al. 1982), the McCarthy Scale (McCarthy 1972), and the Reynell Developmental Language Scale (Reynell 1985).

Including clinical trial, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, review, and systematic reviews, we found 2,332 papers in 8 search engines. We excluded papers not written in English or based on animal models, and after reading the title, abstract, or full article, only 22 studies met inclusion criteria (Table 1).

The majority of the literature focused on the birth outcomes (birth weight, length of gestation, Apgar score) for the infants following treatment of the mother’s depression. To our knowledge, there are only a very few studies that examined short- and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes for the baby. This is true especially for therapies other than drugs. In 19 papers out of the 22 selected, mothers were treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) as citalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, and escitalopram, or serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) as venlafaxine. We found only one paper that analyzed the effects of docosahexanoic acid (DHA)-rich fish oil capsules and two papers that explored massage therapy. Only the studies on alternative therapies were randomized controlled trials with a placebo group of depressed mothers. All the other studies were prospective cohort studies.

Results

The selected papers were arranged in ascending order according to the age of the babies at the time of assessment, from birth until 86 months old. The following sections evaluate short-term effects (from birth to 8 weeks) (Table 2) and long-term effects (from 2 to 86 months) (Table 3) on offspring neurodevelopmental outcomes of different treatments for antenatal maternal depression.

Short-term effects

Antidepressants

The five studies that met inclusion criteria found significant differences in the neurobehavioral scores on both the NBAS and NNNS of newborns exposed to drugs, those exposed to untreated maternal depression, and newborns of healthy women (Smith et al. 2013; Salisbury et al. 2011; Rampono et al. 2009, Ferreira et al. 2007; Zeskind and Stephens 2004); only one study did not find any significant differences (Suri et al. 2011). The most common finding was that infants exposed to drugs displayed more tremors, agitation, irritability, spasms, and hyper or hypotonia than infants of healthy women. Some of these symptoms have been referred to as “neonatal adaptation syndrome” (Grigoriadis et al. 2013), although the studies described here tend to present a wider range of motor and behavioral symptoms, and all studies have used standardized tests of neurodevelopmental outcomes administered by trained staff, as opposed to questionnaire or clinical notes.

In a recent study, Smith et al. (2013) compared neurobehavioral outcomes between neonates who were born to euthymic women who either took or did not take an SSRI during the last trimester of pregnancy. The study found significant differences on motor cluster scores on the NBAS. Exposed infants had lower scores than unexposed, specifically on the pull-to-sit item on the motor cluster, which measures traction, head control, and neck muscle strength. The significant differences on motor cluster became marginal (p = 0.05) after adjustment for gestational age. No other significant differences were found regarding infants sleep state and motor activity. Since other studies have documented that exposure to maternal depression during the third trimester could affect the newborn, only women who were euthymic during the third trimester were used as the comparison group (Hernandez-Reif et al. 2006; Hollins 2007; Lundy et al. 1999b). However the study of Smith et al. (2013) was very limited due to the number (five) of exposed infants assessed.

Salisbury et al. (2011) found lower scores on quality of movement, such as hypertonic reflexes, startles, tremors, back-arching, and a greater number of the central nervous system stress signs, in infants exposed to SSRI compared with those exposed to untreated depression or to infants of healthy women. These differences were not related to depression severity or timing or length of SSRI exposure. Newborns exposed to depression had the highest quality of movement scores but significantly lower scores on attention items compared to the other two groups. These findings are similar to other studies cited above, even though they used a more recent test, the NNNS test, developed by Lester and Tronick (2004). The NNNS test assesses the following: neurological functions, as active and passive tone, reflexes and central nervous system integrity; behavioral items including state, sensory, and interactive response; stress and abstinence items. In the other three selected studies, different antidepressants that work on reuptake of norepinephrine or dopamine, such as venlafaxine and bupropion, were used, in addition to SSRI. Main effects were found on the motor and autonomic clusters of the NBAS, which were similar to other studies cited above (Rampono et al. 2009; Ferreira et al. 2007; Zeskind and Stephens 2004).

Suri et al. (2011) reported no significant differences between newborns of mothers with a history of major depressive disorder, those exposed to antidepressants in utero, and a control group born to healthy mothers. The newborns exposed to antidepressant had significantly lower scores on the rapidity of buildup item under the range of state cluster and on the response to inanimate auditory stimulation item under the orientation cluster and higher score on the defensive scale under the motor cluster when compared to the other two groups. The differences were however small and could be due to some of the limitations of the study: the numbers in each group were small, the grouping of multiple antidepressants did not allow for the differentiation of the effects of each single drug, and the use of different settings at home or in hospital for the NBAS assessment.

Alternative therapies

Only two studies on alternative therapies for maternal depression and the short-term effects on infant neurodevelopmental outcomes met our inclusion criteria. Field et al. widely studied the effects of depression on the health of women and babies during pregnancy and the benefits of massage therapy for pregnant women (Field 2011; Field et al. 2006; Field et al. 1999). In two randomized clinical trials (Field et al. 2004, 2009), they assessed the effects of massage therapy. The NBAS was used to examine the neurobehavioral development of infants in both studies. The massage therapy was carried out over two sessions of 20 min per week during the second and third trimester of pregnancy. The massage was performed by “significant others” of the women who were then trained by massage therapists.

In the 2004 study, newborns born to mothers in the massage therapy group had better performance on the NBAS with significant better scores than the control group on the habituation, range of state, autonomic stability, withdrawal scales, depressed scale, and motor maturity scale. In the study conducted in 2009, the newborns of the massage group performed significantly better on the NBAS on habituation, orientation, motor, and depression score items. In addition, they had lower cortisol levels that could be related to the lower cortisol level of massage therapy mothers. Moreover, after the massage therapy, the newborns tended to have better neonatal outcome with fewer incidences of low birth weight and prematurity in both studies.

Long-term effects

To evaluate the long-term effects of drugs or alternative therapies, babies’ outcomes were divided into three categories: psychomotor, mental, and cognitive development, according to the tests used in the selected papers.

Antidepressants

Four studies (Hanley et al. 2013; Casper et al. 2011; Mortensen et al. 2003; Casper et al. 2003) found significant negative associations between treatments with antidepressants and psychomotor development scores on the Bayley scale (Bayley 1993) and on the Boel test (Junker et al. 1982). In a recent study, Hanley et al. (2013) studied the effects of exposure to SSRI on 10-month-old babies whose mothers took antidepressants throughout the pregnancy. They found that infants who were exposed to drugs in the antenatal period scored significantly lower on the gross motor, social-emotional, and adaptive behavior items compared with those not exposed. They also investigated the effects of maternal mood during pregnancy and postpartum on infants’ development, and found no significant effects of exposure to antidepressants in any of Bayley items.

Similar results were found by Mortensen et al. (2003). A higher percentage of abnormal Boel items, a psychomotor development test based on 14 items (Junker et al. 1982), were found among exposed compared those who were not exposed to antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs. Casper et al. conducted two studies (2003, 2011) to evaluate the effects of antenatal exposure to antidepressants on children born to depressed mothers. In the first study, they found significant lower scores for the Psychomotor Development Index and Motor Quality Factor of the Bayley Behavioural Rating Scale (a subscale of the Bayley that assesses qualitative aspects of the child’s behavior during the testing situation) in the group exposed to antidepressants compared with unexposed children. In the last study, they also evaluated the effects of the duration of exposure to SSRI and found a significant negative correlation between the length of the exposure and the psychomotor development index, while no significant correlations were found with the mental development index. Oberlander et al. (2004) did not found any significant differences in the Bayley assessment at 2 and 8 months in the Psychomotor Development Index (PDI) between newborns exposed or not exposed to antidepressants. They found a higher incidence of poor neonatal adaptation syndrome at birth in newborns exposed to SSRI alone or in combination with benzodiazepine, especially those who were exposed to the combination of paroxetine and clonazepam. Within the entire exposed group, 30 % of newborns, compared with 9 % of control group, showed symptoms of mild respiratory distress, hypotonia, jittery, tremors and hypertonia, cardiac arrhythmia, bradycardia, and hypoglycemia. After 48 h, symptoms had disappeared in all babies. These findings are in agreement with a recent study by Jordan et al. (2008), and a review by Moses-Kolko et al. (2005) where poor neonatal adaption syndrome, including SSRI withdrawal, SSRI toxicity, serotonergic excess, serotonergic CNS adverse effects, serotonin syndrome, and neonatal behavioral syndrome, affects 25–30 % of newborns whose mothers took SSRI antidepressants during pregnancy, with an overall risk ratio of 3.0 (95 % CI 2.0–4.4).

None of the selected studies found significant differences in the Mental Development Index (MDI) of the Bayley scale or in the General Cognitive Index (GCI) of the McCarthy scale (Table 2). However significant differences were found in the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (Nulman et al. 2012). In this recent study, Nulman et al. (Nulman et al. 2012) compared the IQ of children exposed to antidepressants during pregnancy with the IQ of children of mothers with untreated depression and the children of healthy mothers. They found that children exposed to venlafaxine or SSRI had a significantly lower score in the full-scale IQ test, in the verbal IQ scale, and in the performance IQ scale of the WPPSI compared to the control group. The IQ of children whose mothers had untreated depression was similar to those of children exposed to drugs, but the IQ value was not significantly lower compared with the control group. Neither the length of the exposure during the pregnancy nor the dosage of the drugs had an effect on any cognitive or behavioral outcome. In her previous studies Nulman et al. (Nulman and Koren 1996, Nulman et al. 1997, Nulman et al. 2002) had established that exposure to tricyclic antidepressants and fluoxetine do not adversely affect the cognitive, language, and behavioral development of children, as measured by the MDI of the Bayley, the McCarthy, and the Reynell scales. The duration of depression and the number of episodes after delivery were negatively associated with IQ and language development.

Other authors (Galbally et al. 2011; Reebye et al. 2002) did not find any significant differences in the cognitive and language scores, as measured by the Bayley, of children exposed to antidepressants and those in the control group. Galbally found a difference on the motor subscale with a moderate Cohen’s effect size for fine and gross motor. Neither Mattson et al. (1999) with the WPPSI nor Morison et al. (2001) with the Bayley found any significant differences between children exposed to SSRI and control group.

Alternative therapies

Only one study on the therapeutic effects of dietary DHA by Makrides et al. (2010) met the criteria to be included in the review. The therapeutic effects of omega-3 during pregnancy were shown to improve gestational outcomes, and its therapeutic use in treating depression has been confirmed by many authors (Larqué et al. 2012; Su et al. 2008), and interestingly, this is the only randomized controlled trial of this systematic review.

Makrides et al. (2010) evaluated the neurodevelopmental effect of DHA treatment on young children, assessed at 18 months. They did not find any significant differences in the cognitive, language, motor, social-emotional, and adaptive behavior standardized scores on the Bayley Scale III Edition (Bayley 2005), between children exposed to DHA-rich fish oil capsules and vegetable oil capsules during pregnancy and a control group of children exposed to placebo. Although in secondary analyses, they noticed two apparently contrasting effects: fewer children in the DHA group had delayed cognitive development compared with the control group, and girls exposed to higher-dose DHA in utero had lower language scores and were more likely to have delayed language development than girls from the control group. In terms of maternal depression, the DHA capsules were not better than control treatment to treat or prevent postpartum depression. The main significant effects found in this study were a decrease in preterm birth (<34-week gestation) and low birth weight in the DHA group compared with the control group.

Discussion

This review summarizes the current literature on the neurodevelopmental outcome of children whose mothers were treated for antenatal depression with antidepressants or alternative therapies. Up until now, the majority of the literature only studied the effects of antidepressants; only a few studies have investigated the effects of alternative therapies on infants. The evidence suggests that antidepressants lead to short-term adverse effects on newborns compared with a control group. The motor and autonomic systems are most affected. Studies show that babies who are exposed to drugs present with more tremors, agitation, irritability, spasms, and hypertonia or hypotonia. Many symptoms are however transient and mild (Jordan et al. 2008; Moses-Kolko et al. 2005). The symptoms found in the newborns could be due to toxicity of the SSRI drugs or to the withdrawal syndrome; a single explanation has still not been found. However, none of these studies were randomized controlled trials, and therefore, depression per se may account for at least some of the effects attributed to antidepressants.

In the long-term, some studies have shown a significant effect of antidepressants on psychomotor development, with delay on motor development on the Bayley and Boel assessments. However, other authors have found no significant difference between those who are exposed and the control group. No differences have been found for mental development of the infant: only Nulman et al. (2012) found significantly lower IQ in children exposed to drugs compared with the control group, on the WPPSI. However, the values were similar in children whose mothers were depressed and treated when compared with children whose mothers were depressed but untreated. They also evaluated the effects of the length of exposure and dosage of the drugs and did not find any significant difference. Moreover, the duration of depression and the number of episodes after delivery were negatively associated with IQ and language development, respectively. Again, this suggests that at least some of the neurodevelopmental differences identified in this kind of studies are due, at least in part, to depression per se. Indeed, there is strong evidence that depression per se can adversely affect the neurodevelopment and emotional development of the offspring through in utero biological programming of fetus development and of maternal caregiving behavior (Glover 2011; Pawlby et al. 2011). The potential rescuing effects of antidepressants on some of these biological mechanisms, such as hypercortisolemia (and Pariante and Lightman 2008), could explain why antidepressant treatment in our review is associated with only minor developmental abnormalities. Of note in this regard is the fact that for obstetric complications, more severe forms of depression (for example, diagnosed as cases using clinical interview as opposed to symptoms scale) tend to have more severe complications (Grote et al. 2010). However, the studies described in this report, which often lack information on diagnostic criteria or symptoms severity, do not allow us to draw any conclusion on the impact of these factors on neurodevelopmental outcomes, and indeed, epidemiological studies have shown that even milder form of depression and anxiety can affect long-term offspring behavior (Glover 2011).

The alternative therapies analyzed in this review did not have any negative impact on children in the short- or long-term and found some positive effects. Massage therapy led to better NBAS scores than control group, and in the DHA therapy group, there were fewer children with delay on cognitive development even if therapy was not significant better than placebo to treat depression. It is important to underline the absence of studies about alternative therapies that look at the impact on the newborn. While overall, these studies show important results with this kind of treatment, the number of studies is small and more randomized/controlled research is needed in this field.

Limitations

As mentioned above, it is important to consider factors other than treatments for maternal depression that could influence neurodevelopmental outcomes of newborns and children. First, the current mental state of the mothers was not considered in all studies. In some cases, mothers only had a history of depression and were taking medication only as prevention or maintenance treatment. The adverse effect of maternal depression on the newborn is well known (Grote et al. 2010). It is important therefore to include the mother’s current mental state when examining the contribution of treatment in altering the neurodevelopmental outcome of the babies. Another limitation is the timing and the length of exposure to the treatment, especially drugs. Casper et al. (2003, 2011) was the only study that considered different trimesters of exposure to antidepressants, and he found a negative correlation between the length of the exposure and the behavioral rating scale on the Bayley assessment. Finally, it is important again to stress that only the studies on alternative therapies (massage therapy and omega-3 fatty acid) were randomized controlled trials with placebo groups; the other studies were prospective or retrospective studies.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first review that has examined the neurodevelopment outcomes of babies exposed in utero to antidepressants and to alternative therapies. While the short-term effects seems to be more consistent, these tend to be mild and self-limiting; in contrast, the results of studies examining long-term effects are more varied, and it is virtually impossible to disentangle the effects of antidepressants from the effects of depression per se. Finally, our findings suggest that alternative therapies may be safer options. Future studies are necessary to test new alternative therapies other than drugs and to provide controlled data on the effects of medications in pregnancy on the neurodevelopmental outcomes of children.

References

Ahokas A, Kaukoranta J, Whalbeck K, Aito J (2005) Relevance of gonadal hormones to perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. In: Riecher-Rossler A, Steiner M (eds) Perinatal stress, mood, and anxiety disorders: from bench to bedside. Bibliotheca Psychiatrica/Karger, Basel, pp 100–111

Bayley N (1993) Bayley Scales of Infant Development, 2nd edn. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio

Bayley N (2005) The Bayley scales of infant development, 3rd edn. Pearson, Mahwah

Bonari L, Pinto N, Ahn E, Einarson A, Steiner M, Koren G (2004) Perinatal risks of untreated depression during pregnancy. Can J Psychiatry 49(11):726–735

Bonari L, Koren G, Einarson TR, Jasper JD, Taddio A, Einarson A (2005) Use of antidepressants by pregnant women: evaluation of perception of risk, efficacy of evidence based counseling and determinants of decision making. Arch Women Ment Health 8(4):214–220

Brazelton TB (1973) Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale. In: Clinics in Developmental Medicine, No 50. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott

Casper RC, Fleisher BE, Lee-Ancajas JC, Gilles A, Gaylor E, DeBattista A, Hoyme HE (2003) Follow-up of children of depressed mothers exposed or not exposed to anti depressant drugs during pregnancy. J Pediatr 142:402–408

Casper RC, Gilles AA, Fleisher BE, Baran J, Enns G, Lazzeroni LC (2011) Length of prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants: effects on neonatal adaptation and psychomotor development. Psychopharmacology 217(2):211–219. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2270-z

Chaudron LH (2013) Complex challenges in treating depression during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatr 170:12–20

Deave T, Heron J, Evans J, Emond A (2008) The impact of maternal depression in pregnancy on early child development. J Obstet Gynaecol 115:1043–1051

Dennis CL, Allen K (2010) Interventions (other than pharmacological, psychosocial or psychological) for treating antenatal depression (review), issue 6 The Cochrane Library

Dennis C-L, Ross LE, Grigoriadis S (2007) Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating antenatal depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Issue 3

Dietz PM, Williams SB, Callaghan WM, Bachman DJ, Whitlock EP, Horbrook MC (2007) Clinically identified maternal depression before, during, and after pregnancies ending in live births. Am J Psychiatr 164:1515–1520

Ferreira E, Carceller AM, Agogue C, Martin BZ, St-Andre M, Francoeur D, Berard A (2007) Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine during pregnancy in term and preterm neonates. Pediatrics 119:52–59

Field T (2011) Prenatal depression effects on early development: a review. Infant Behav Dev 34(1):1–14

Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Hart S, Theakston H, Schanberg S, Kuhn C (1999) Pregnant women benefit from massage therapy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 20:31–38

Field T, Diego MA, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C (2004) Massage therapy effects on depressed pregnant women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 25:115–122

Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M (2006) Prenatal depression effects on the fetus and newborn: a review, infant behavior development. Dev 29:445–455

Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M, Deeds O, Figueiredo B (2009) Pregnancy massage reduces prematurity, low birthweight and postpartum depression. Infant Behav Dev 32:454–460

Galbally M, Lewis AJ, Buist A (2011) Developmental outcomes of children exposed to antidepressants in pregnancy. Aust N Z J Psychiatr 45(5):393–399

Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T (2005) Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 106:1071–1083

Gentile S, Galbally M (2011) Prenatal exposure to antidepressant medications and neurodevelopmental outcomes: A systematic review. J Affect Disord 128:1–9

Glover V (2011) Annual research review: prenatal stress and the origins of psychopathology: an evolutionary perspective. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 52:356–367

Grigoriadis S, VonderPorten EH, Mamisashvili L, Eady A, Tomlinson G, Dennis CL, Koren G, Steiner M, Mousmanis P, Cheung A, Ross LE (2013) The effect of prenatal antidepressant exposure on neonatal adaptation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 74:e309–e320

Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ (2010) A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatr 67:1012–1024

Hanley GE, Brain U, Oberlander TF (2013) Infant developmental outcomes following prenatal exposure to antidepressants, and maternal depressed mood and positive affect. Early Hum Dev 89:519–524

Hernandez-Reif M, Field T, Diego M, Ruddock M (2006) Greater arousal and less attentiveness to face/voice stimuli by neonates of depressed mothers on the brazelton neonatal behavioral assessment scale. Infant behavior development 29(4):594–598

Hollins K (2007) Consequences of antenatal mental health problems for child health and development. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 19(6):568–572

Jordan AE, Jackson GL, Deardorff D, Shivakumar G, McIntire DD, Dashe JS (2008) Serotonin reuptake inhibitor use in pregnancy and the neonatal behavioral syndrome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 21(10):745–751

Junker KS, Barr B, Maliniemi S, Wasz-Hockert O (1982) BOEL—a screening program to enlarge the concept ofinfant health. Paediatrician 11:85–89

Koren G, Nordeng H (2012) Antidepressant use during pregnancy: the benefit-risk ratio. Am J Obstet Gynecol 207(3):157–163

Larqué E, Gil-Sánchez A, Prieto-Sánchez MT, Koletzko B (2012) Omega 3 fatty acids, gestation and pregnancy outcomes (review). Br J Nutr 107(2):S77–S84

Lattimore KA, Donn SM, Kaciroti N, Kemper AR, Neal CR Jr, Vazquez DM (2005) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use during pregnancy and effects on the fetus and newborn: a meta-analysis. J Perinatol 25:595–604

Leigh B, Milgrom J (2008) Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry 8:24

Lester BM, Tronick EZ (2004) History and description of the neonatal intensive care unit network neurobehavioral scale. Pediatrics 113:634–640

Lundy B, Field T, Nearing G, Davalos M, Pietro PA, Schanberg S, Kuhn C (1999a) Prenatal depression effects on neonates. Infant behavior development 22:119–129

Lundy B, Field T, Nearing G, Davalos M, Pietro PA, Schanberg S, Kuhn C (1999b) Prenatal depression effects on neonates. Infant behavior development 22:119–129

Makrides M, Gibson RA, McPhee AJ, Yelland L, Quinlivan J, Ryan P, DOMInO Investigative Team (2010) Effect of DHA supplementation during pregnancy on maternal depression and neurodevelopment of young children: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc 304:1675–1683

Marchesi C, Bertonui S, Maggini C (2009) Major and minor depression in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 113:1292–1298

Marcus SM (2009) Depression during pregnancy: rates, risks and consequences. Motherisk update 2008. Can J Clin Pharmacol 16(1):e15-22

Marino M, Battaglia E, Massimino M, Aguglia E (2012) Risk factors in post partum depression. Rivista di Psichiatria 47(3):187–194

Mattson S, Eastvold A, Jones K et al (1999) Neurobehavioral follow- up of children prenatally exposed to fluoxetine [Abstract]. Teratology 59:376

McCarthy D (1972) McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities. Psychological Corporation, New York

Morison SJ, Grunau RE, Oberlander TF et al (2001) Infant social behavior and development in the first year of life following prolonged prenatal psychotropic medication exposure [Abstract]. Pediatr Res 49(4 Pt 2 Suppl):28A

Mortensen JT, Olsen J, Larsen H, Bendsen J, Obel C, Sorensen HT (2003) Psychomotor development in children exposed in utero to benzodiazepines, antidepressants, neuroleptics, and anti-epileptics. Eur J Epidemiol 18:769–771

Moses-Kolko EL, Bogen D, Perel J, Bregar A, Uhl K, Levin B, Wisner KL (2005) Neonatal signs after late in utero exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: literature review and implications for clinical applications. J Am Med Assoc 293:2372–2383

NICE clinical guideline 45Antenatal and postnatal mental health Clinical management and service guidance. Issued: February 2007 last modified: April 2007guidance.nice.org.uk/cg45

Nulman I, Koren G (1996) The safety of fluoxetine during pregnancy and lactation. Teratology 53:304–308

Nulman I, Rovet J, Stewart DE, Wolpin J, Gardner HA, Theis JG, Kulin N, Koren G (1997) Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to antidepressant drug. N Engl J Med 336(4):258–262

Nulman I, Rovet J, Stewart DE, Wolpin J, Pace-Asciak P, Shuhaiber S, Koren G (2002) Child development following exposure to tricyclic antidepressants or fluoxetine throughout fetal life: a prospective, controlled study. Am J Psychiatr 159:1889–1895

Nulman I, Koren G, Rovet J, Barrera M, Pulver A, Streiner D, Feldman B (2012) Neurodevelopment of children following prenatal exposure to venlafaxine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or untreated maternal depression. Am J Psychiatr 169(11):1165–1174

Oberlander TF, Misri S, Fitzgerald CE, Kostaras X, Rurak D, Riggs W (2004) Pharmacologic factors associated with transient neonatal symptoms following prenatal psychotropic medication exposure. J Clin Psychiatry 65(2):230–237

Pariante CM, Lightman SL (2008) The HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci 31:464–468

Pawlby S, Hay D, Sharp D, Waters CS, Pariante CM (2011) Antenatal depression and offspring psychopathology: the influence of childhood maltreatment. Br J Psychiatry 199:106–112

Rampono J, Simmer K, Ilett KF, Hackett LP, Doherty DA, Elliot R, Kok CH, Coenen A, Forman T (2009) Placental transfer of SSRI and SNRI antidepressants and effects on the neonate. Pharmacopsychiatry 42:95–100

Reebye P, Morison SJ, Panikkar H, Misri S, Grunau RE (2002) Affect expression in prenatally psychotropic exposed and nonexposed mother–infant dyads. J Ment Health 23(4):403–416

Reynell JK (1985) Reynell developmental language scales manual. 2nd rev. (Huntley M.) Windsor. NFER-NELSON Publishing, England

Salisbury AL, Wisner KL, Pearlstein T, Battle CL, Stroud L, Lester BM (2011) Newborn neurobehavioral patterns are differentially related to prenatal maternal major depressive disorder and serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment. Depress Anxiety 28(Issue 11):1008–1019

Smith MV, Sung A, Shah B, Mayes L, Klein DS, Yonkers KA (2013) Neurobehavioral assessment of infants born at term and in utero exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Early Hum Dev 89(2):81–86

Su KP, Huang SY, Chiu TH, Huang KC, Huang CL, Chang HC, Pariante CM (2008) Omega-3 fatty acids for major depressive disorder during pregnancy: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 69:644–651

Suri R, Hellemann G, Stowe ZN, Cohen LS, Aquino A, Altushuler LL (2011) A prospective, naturalistic, blinded study of early neurobehavioral outcomes for infants following prenatal antidepressant exposure. J Clin Psychiatry 72(7):1002–1007

Wechsler D (1981) Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Revth edn. Psychological Corporation, New York

Wechsler D (1999) Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI). San Antonio, Tex, Harcourt Assessment

Wechsler D (2002) Wechsler Primary and Preschool Scale of Intelligence,3rd ed (WPPSI-III). San Antonio, Tex, Harcourt Assessment

Wisner KL, Zarin D, Holmboe ES, Appelbaum PS, Gelenberg AJ, Leonard HL, Frank E (2000) Risk-benefit decision making for treatment of depression during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatr 157:1933–1940

Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, Oberlander TF, Dell DL, Stotland N, Ramin S, Chaudron L, Lockwood C (2009) The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the american psychiatric association and the american college of obstetricians and gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 114:703–713

Zeskind PS, Stephens LE (2004) Maternal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use during pregnancy and newborn neurobehavior. Pediatrics 113(2):368–375

Acknowledgments

CMP is supported by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London.

Conflict of interest

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. CMP receive research funding from pharmaceutical companies interested in the development of antidepressants, but the paper is unrelated to this funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Previti, G., Pawlby, S., Chowdhury, S. et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome for offspring of women treated for antenatal depression: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health 17, 471–483 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0457-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0457-0