Abstract

Plants are a rich source of new antiviral, pharmacologically active agents. The naturally occurring plant alkaloid berberine (BBR) is one of the phytochemicals with a broad range of biological activity, including anticancer, anti-inflammatory and antiviral activity. BBR targets different steps in the viral life cycle and is thus a good candidate for use in novel antiviral drugs and therapies. It has been shown that BBR reduces virus replication and targets specific interactions between the virus and its host. BBR intercalates into DNA and inhibits DNA synthesis and reverse transcriptase activity. It inhibits replication of herpes simplex virus (HSV), human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), human papillomavirus (HPV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). This isoquinoline alkaloid has the ability to regulate the MEK-ERK, AMPK/mTOR, and NF-κB signaling pathways, which are necessary for viral replication. Furthermore, it has been reported that BBR supports the host immune response, thus leading to viral clearance. In this short review, we focus on the most recent studies on the antiviral properties of berberine and its derivatives, which might be promising agents to be considered in future studies in the fight against the current pandemic SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

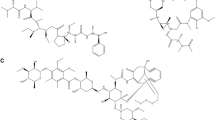

Berberine (BBR) is a natural isoquinoline alkaloid with low toxicity. It is present in several medicinal plants, such as Berberis vulgaris, Coptis chinensis, Hydrastis canadensis, Coptidis rhizoma, Xanthoriza simplicissima, Phellodendron amurense, and Chelidonium majus. Berberine exhibits unusual biochemical and pharmacological activities, including antidiabetic [1], hypolipidemic [2], antihypertensive [3], anti-inflammatory [4], antidiarrheal [5], hepatoprotective [6], antidepressant [7], anticancer [8], antibacterial [9], and antiviral [10] properties. BBR is capable of penetrating all cell lines, but the cumulative concentration is the highest in Hep G-2 cells [11]. It can cross the blood-brain barrier when it is administrated systematically, and it has a protective effect on the central nervous system [12]. Due to its various properties, BBR is widely used as a dietary supplement. It has low toxicity and is well tolerated by the human body. However, high doses of BBR can cause gastrointestinal side-effects. In liver cells, BBR is metabolized with the participation of cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP1A2), cytochrome P450 3A4 (3A4), cytochrome P450 2D6 (2D6), and UDP glucuronosyltransferases. In phase I, it is metabolized by demethylation, and in phase II, by glucuronidation. Its metabolites are berberrubine, demethylene-berberine, jatrorrhizine, thalifendine, and its glucuronidated derivatives [Fig. 1] [13,14,15]. BBR is administered by oral gavage, but its bioavailability is low. Currently, nanomaterials can be applied as an effective drug delivery system providing time-controlled and site-specific delivery of the loaded drug. Conjugation of BBR with liposomes or micelles allows its bioavailability to be improved. In recent years, empirical evidence has shown that this bioactive plant alkaloid possesses strong antiviral activity against different viruses. The antiviral activity of BBR against herpesviruses, influenza virus, and respiratory syncytial viruses has been scientifically documented. Its potential activity against SARS-CoV and other coronaviruses, as discussed below, also raises the question if it could be effective against the novel pandemic SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, which is currently an overwhelming public-health problem worldwide. The search for novel therapeutics against this virus and the symptoms of its disease, COVID-19, are of the highest importance.

Mode of the antiviral activity of berberine

Viruses modulate and utilize many host cellular processes for their replication. Virus infection can result in changes in cellular metabolism and signaling that facilitate viral replication. These processes involve different molecules, including nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs). NF-κB is a DNA-binding protein that is required in the transcription of various genes involved in controlling cellular processes, in particular, inflammatory and immune responses. The modulation of NF-κB pathway by BBR is one of the mechanisms that inhibits virus infection. BBR downregulates virus-induced NF-κB activation and blocks degradation of the endogenous NF-κB inhibitor IκBα. MAPKs are involved in the regulation of key cellular signaling pathways, such as apoptosis, differentiation, proliferation, and immune responses. MAPKs play an essential role in infection and cellular stress. Moreover, they are known to promote survival and generation of progeny virions. Four subgroups of MAPKs have been identified, namely, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1 and 2, ERK5, isoforms of p38 protein (p38), and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) [16]. The JNK and p38 pathways play a key role in inflammation and tissue homeostasis. MAPKs are responsible for the phosphorylation of serine and threonine in many proteins. Phosphorylation plays a significant role in protein interactions, protein folding, and activation and deactivation of enzymes. ERK kinases phosphorylate multiple substrates, such as c-Fos and Elk 1, which are involved in the regulation of cell cycle progression and survival. Protein phosphorylation also plays an essential role in the infection cycle of many viruses [17]. A number of viruses induce or inhibit the phosphorylation of cellular proteins at all levels of signal transmission pathways from the plasma membrane to the nucleus. Phosphorylation can affect a viral protein’s stability, activity, interaction with other cellular and viral proteins, and infectivity. Viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [18], hepatitis C virus (HCV) [19], and coronavirus type 2 [20] activate the phosphorylation of MAPK. Changes in the phosphorylation of proteins have been observed during viral replication. For example, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protein p6 is phosphorylated at a specific site (Thr 23) by MAPK and ERK-2. Mutational analysis has demonstrated that Thr 23 is important for the infectivity, maturation, and budding of viral particles [21]. Phosphorylation of the coat protein (CP) of RNA viruses can significantly affect CP-RNA interactions, the stability of viral particles, and the viral infection processes [22, 23]. Moreover, many viruses use phosphorylation of proteins to modulate signaling in order to prevent apoptosis and promote cellular survival and proliferation [24].

An example is chikungunya virus (CHIKV). It is transmitted to humans mainly by infected mosquitoes, specifically Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. CHIKV causes fever, joint swelling, headache, and severe persistent muscle and joint pain in humans. CHIKV belongs to the family Togaviridae and has a positive-sense RNA genome. Host macrophages are the major cellular reservoirs of CHIKV during infection, and the production of the cytokines TNF, IL-1β, and IL-6, IL-8 may be associated with viral pathogenesis. During CHIKV infection, the major mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways, p38, JNK, and ERK are activated. Activation of ERK and JNK kinases are essential for generation of CHIKV progeny virions. The specific molecular mechanism of CHIKV-induced MAPKs is not known. It has been shown that CHIKV can modulate the phosphorylation of p38 and JNK. Recently, it was demonstrated that the CHIKV nsP2 protein interacts with p38 and JNK in host macrophages [25]. In addition, JNK modulates the replication of certain viruses. For example, replication of HSV, HIV, and rotaviruses is suppressed by JNK inhibition, while the replication of influenza virus is increased. CHIKV induces MAPK activation as well as expression of viral nonstructural and structural proteins. Varghese et al. showed that BBR significantly reduces CHIKV-induced activation of MAPKs. The P38, ERK and JNK signaling pathways are strongly inhibited upon treatment with BBR, which especially targets the ERK signaling pathway, resulting in a marked reduction in particle formations. The reduction in viral protein expression after BBR treatment is probably a consequence of a decrease in virus-induced signaling. BBR treatment does not inhibit virus entry or the enzymatic activity of the viral replicase [26]. Furthermore, CHIKV induces prosurvival signal cascades such as PI3K-AKT and autophagy [27]. It has also been reported that BBR significantly reduces phosphorylation of p38 MAPK during respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection [28]. p38 MAPK is induced in the early stage of RSV infection [29]. Inhibition of the activity of p38 MAPK by BBR has also been observed during hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. HBV is a member of the family Hepadnaviridae. Its virion contains a partially double-stranded relaxed circular DNA (rcDNA) genome, which, in the nucleus of an infected cell, is converted to covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). p38 MAPK plays a central role in the maintenance of HBV cccDNA in infected cells [30]. The cccDNA acts as a template for RNA synthesis, including mRNAs and pregenomic RNAs (pgRNAs). During the life cycle of HBV, pgRNA is converted to partially double-stranded rcDNA in the capsid by reverse transcriptase (RT). Inhibition of the activity of p38 MAPK is positively correlated with the suppression of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) production, HBV e-antigen (HBeAg) secretion, and inhibition of HBV replication. It has been reported that BBR also intercalates into DNA, inhibiting DNA synthesis and reverse transcriptase activity [31,32,33,34]. HBV infection is associated with a broad spectrum of liver diseases, including acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. About a million deaths globally are caused by HBV-related diseases each year, with more than a million people suffering from chronic hepatitis B worldwide [35]. The ability of BBR to inhibit MAPK might make it a potential candidate for a new antiviral agent against HBV infection. p38 MAPK has been suggested as a possible target for anti-HBV therapy. Kim et al. showed that biphenyl amides act as p38 MAPK inhibitors and suppress HBsAg secretion [36]. Curcumin, another well-known alkaloid, decreases the level of HBsAg and reduces the number of cccDNA copies, thus inhibiting HBV replication and expression. Moreover, this natural plant compound reduces the acetylation level of cccDNA-bound histone H3 and H4 [37]. The current anti-HBV therapy options have disadvantages. These include high cost and cumulative toxicity, which results in bone disease and renal injury. Additionally, the therapy is limited to patients with viremia and elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or fibrosis [38], and the MAPK pathway appears to be activated by other viruses, such as HCV [39], dengue virus [40], coronavirus [41], Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) [42], and enterovirus 71 (EV71) [43].

Another strategy that plays an important role in the replication of some viruses is autophagy. Autophagy is an intracellular degradation process that helps to maintain cellular homeostasis under both normal and stress conditions. It is a dynamic process starting with autophagosome formation, followed by fusion with lysosomes and degradation of the enclosed cargo. Autophagy is also an antiviral mechanism that selectively degrades viral components or viral particles inside lysosomes [44]. One example of a virus that exploits autophagy is the enterovirus EV71, a member of the family Picornaviridae. Picornaviruses are nonenveloped viruses with a positive-stranded RNA genome of 7.5 kb that contains a single open reading frame (ORF) flanked by 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions. This RNA serves as a template for translation of the viral polyprotein and for the amplification of the viral genome. Viral replication takes place on intracellular membranous structures and is dependent on autophagy. Enteroviruses induce autophagy to promote their own replication [45]. The mechanism responsible for this pro-viral function of autophagy is unknown. EV disrupts autophagosome-lysosome fusion, which allows viral RNA and proteins to escape degradation and consequently facilitates viral replication by providing membranes for replication, leading to pathogenesis in the host. EVs are associated with neurological disorders, cardiovascular damage, and metabolic disease. Recently, it has been reported that BBR can inhibit virus-induced autophagy and reduce viral RNA and protein synthesis [46]. BBR inhibits EV71-induced autophagy by affecting JNK, PI3KIII and AKT signaling. For example, BBR treatment increases AKT phosphorylation and reduces JNK and PI3KIII phosphorylation. JNK signaling is involved in autophagy, and its inhibition can inhibit this process. BBR also inhibits the MEK/ERK signaling pathway, which is important for mediating innate immunity to viral infections and plays a significant role in EV71 replication and pathogenesis [43, 46]. This suggests that BBR acts by inhibiting MAPK signaling and is a potential agent for the treatment of enterovirus infection, especially since there are no other effective and licensed drugs available.

Activity of berberine against different viruses

Activity of BBR against viruses of the family Flaviviridae

In the past decades, HCV has become a major public-health problem globally. At present, there is no effective vaccine against this virus. HCV is an enveloped, positive-strand RNA virus belonging to the family Flaviviridae. HCV infection is associated with a broad spectrum of liver diseases, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The viral proteins E1 and E2 mediate entry of the virus into cells, which is a key step in its life cycle. The HCV E2 is primarily responsible for preventing premature membrane fusion, as well as stabilizing attachment of the virus to cells. Hong et al. have shown that BBR suppresses hepatitis C virus replication by targeting the viral E2 glycoprotein, specifically blocking HCV attachment and entry. Molecular docking studies have indicated that BBR interacts with the HCV E2 glycoprotein [47], suggesting that BBR could be a good candidate for the development of entry inhibitors for the prophylaxis and treatment of HCV infection. The antiviral effect of BBR does not seem to involve modulation of host cell functions such as the interferon response [47,48,49]. BBR also exhibits antiviral activity against dengue virus (DENV) and Zika virus (ZIKV) infections. Both of these viruses belong to the family Flaviviridae. DENV has four serotypes (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4), which are transmitted to humans by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. The virus is responsible for diseases of different severity, including asymptomatic infection, dengue fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), and dengue shock syndrome (DSS), which can be fatal [50]. ZIKV infection can cause congenital syndromes including microcephaly, spasticity craniofacial disproportion, irritability, seizures, and other brain dysfunctions [51]. The non-structural viral proteins NS5 and NS3 are crucial for the replication of the DENV and ZIKV genome. In an in silico study by Srivastava, BBR was docked with NS5 methyltransferase of DENV and the NS3 protein of ZIKV using the AutoDock 4.2 tool [52]. The results suggested that BBR might be a novel inhibitor of the non-structural proteins (NS5 and NS3) of DENV and ZIKV with potential to prevent infection. However, this needs to be studied experimentally.

Activity of BBR against viral-borne respiratory syndromes

BBR is also a possible remedy for infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), the etiological agent of the respiratory disease SARS. SARS-CoV belongs to the family Coronaviridae. Recently, coronaviruses have drawn much attention due to the current pandemic, which has life-threatening health consequences. SARS-CoV is an enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA with a genome of 29.7 kbp. During infection, the SARS-CoV proteins nsp1, nsp2, nsp7, spike, and nucleocapsid promote NF-κB activation. NF-κB is a DNA-binding protein that regulates the transcription of different genes whose products are involved in the control of cellular processes such as inflammatory and immune responses. During SARS-CoV infection, the virus regulates the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF, CCL2, and CXCL2. BBR has an inhibitory effect on the NF-κB signaling pathway and therefore might function as an antiviral agent against coronavirus infection [53, 54]. Recent studies have indicated that an extract from Coptidis rhizoma containing BBR and other protoberberine alkaloids might inhibit coronavirus RNA synthesis and viral assembly and release [55]. It might be worth investigating the potential of BBR against SARS-CoV-2 in future studies.

Shinae et al. showed that the replication of RSV was significantly reduced by treatment with BBR [56]. RSV is a member of the family Paramyxoviridae and has a negative-sense, nonsegmented RNA genome. RSV infects the respiratory tract of most children before their second birthday and is a common cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants under the age of 1 year [57]. It has also been recognized as a significant cause of respiratory illness in older adults. During RSV infection, phosphorylation of p38 MAPK occurs at a very early stage of virus replication, and this phosphorylation can be reduced by BBR treatment. The precise molecular mechanism of this inhibition is still unknown, but recent studies have demonstrated that the effect of BBR is based on its direct interaction with a component of the TLR4 receptor complex. BBR can inhibit TLR4 activation and thus suppress p38 MAPK activation.

In addition, the production of interleukin 6 (IL-6) mRNA upon RSV infection is suppressed by BBR, which indicates its anti-inflammatory role during RSV infection [58]. It has been shown that BBR functions through several pathways, such as the NF-κB, ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK. As a consequence, these functions decrease the levels of several proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (Il-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). BBR also inhibits the phosphorylation of NF-κB and IκBα) [59].

Anti-influenza activity

Although influenza virus often causes only mild respiratory illness, influenza can be a life-threatening infectious disease, especially in children, seniors, and immunocompromised patients. Yan et al. observed an antiviral effect of BBR against influenza H1N1 virus [60]. In some countries, seasonal influenza affects up to 40% of the population annually, and worldwide, up to 500 million people die from it each year [61, 62]. Influenza viruses (types A, B, C) are segmented, negative-strand RNA viruses belonging to the family Orthomyxoviridae. Influenza A viruses of various subtypes infect many animal species (e.g., birds, swine, horses, dogs, marine mammals, and felids) as well as humans. Influenza A viruses are classified into highly pathogenic subtypes based on their surface glycoproteins, with 17 hemagglutinin (HA) and 10 neuraminidase (NA) subtypes currently recognized. The neuraminidase and hemagglutinin proteins dominate the virion surfaces and are responsible for virus infectivity. NA plays a role in virus replication by releasing new virus particles from host cells, separating them from the neuraminic-acid-containing glycan structures on the surface of the infected cell.

Yan et al. showed that BBR inhibits influenza virus replication in human pulmonary adenocarcinoma cells (cell line A549) and mouse lungs by suppressing the infection. This research confirmed that BBR inhibits the expression of TLR7 and NF-κB, both of which are upregulated in influenza-infected lung tissues [63]. The infection is recognized by host pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), for example, Toll-like receptors (TLRs), whose signaling pathways converge on two families of transcription factors: NF-κB and interferon regulatory factor (IRF). Both of these factors are translocated to the nucleus, where they upregulate proinflammatory and antiviral responses [64]. Kim et al. showed that extracts from Cortex Phellodendri enriched in BBR can regulate the antiviral host response. It has been shown that BBR modulates the generation of proinflammatory substances such as cytokines and stimulates the antiviral state in infected host cells. The potential therapeutic mechanism of BBR in influenza-associated viral pneumonia might be the result of both inhibition of the viral infection and modulation of the release of inflammatory factors [65, 66]. Other studies have shown that BBR and its derivatives also inhibit cytopathogenic effects and neuraminidase (NA) activity in vitro. Enkhtaivan et al. showed that the active site of the viral NA can be blocked by berberine derivatives (BDs) (Table 1) in the same way as it is blocked by the antiviral drug oseltamivir (a well-known NA inhibitor) [65]. The inhibition of viral NA was confirmed in a molecular docking study using BD and the neuraminidases of both influenza A and B viruses [67].

Using this example of the anti-influenza activity of BBR and its derivatives, we can see that BBR is multifunctional and acts through diverse mechanisms. It can attach to protein molecules at their active sites, hence directly blocking their activity, as is the case with the influenza virus NA protein [67], and it can activate different signaling pathways leading to antiviral activity, e.g., inhibition of the expression of TLR7 and NF-κB [64]. The regulatory effects of BBR on the TLR signaling pathway has also been shown to affect the process of intestinal mucosal damage in rats, but the exact molecular interactions between BBR and other molecules remain to be identified. However, based on the existing evidence, we might assume that they rely on binding of BBR to their active sites [68].

Anti-inflammatory properties of BBR

BBR has also anti-inflammatory properties and is able to inhibit inflammatory cell infiltration and the production of TNF-α, IL-13, Il-6, IL-8 and IFN-γ [69]. This may occur through the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and inhibition of NF-κB. It is noteworthy that in some viral infections, e.g., human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and Ebola virus, AMPK activation has an adverse effect. The mechanism of the anti-inflammatory effect of BBR is complex. BBR can inhibit the binding activity NF-κB and activator protein 1 (AP1). AP1 and NF-κB are key transcription factors that are responsible for regulating the expression of many genes involved in inflammation [69]. Moreover, the anti-inflammatory properties of BBR also involve the modulation of MAPKs. BBR can inhibit generation of proinflammatory cytokines and moderate the inflammatory response. During RSV infection, BBR decreases interleukine-6 (IL-6) mRNA level. In influenza virus infection, BBR reduces the mRNA expression of TLR7 and NF-κB in lung tissue [70].

Inflammation is an important aspect of the pathogenesis of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) and is associated with the upregulation of multiple mediators, such as TLR signaling, cytokines, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), TNF-α, TGF-β, interleukins, and chemokines [65]. VEEV is a member of the genus Alphavirus, family Togaviridae, and has a positive-sense RNA genome. This virus causes severe encephalitis in humans. Four antigenic varieties of VEEV are known, namely IA/B, IC, ID and IE. Three of them, subtypes IA, IB and C are the epizootic strains that cause disease and lead to high mortality in equines. VEEV infection in humans is asymptomatic during the first 1-5 days, followed by the onset of a febrile illness that is characterized by fever, vomiting, headaches, myalgia, ocular pain, or diarrhea, which can last for 1-4 days. The disease can then progress to severe neurological disease, with an incidence of almost 14% [72]. Recent research suggests that BBR might be a potential therapeutic agent against VEEV [65].

Anti-HPV effect

BBR also suppresses human papillomavirus (HPV) transcription. HPVs are non-enveloped, epitheliotrophic viruses with a circular double-stranded DNA genome that belong to the family Papillomaviridae. Persistent infection with high-risk HPVs, such as HPV16 and HPV18, can lead to the development of cervical cancer. Cancer development and progression are driven by the expression of two oncogenes, E6 and E7. Their expression is mainly dependent on the viral E2 protein and on the availability of the host transcription factor activator protein 1 (AP1). HPV E6 and E7 interact with tumor suppressor proteins, p53 and Rb, respectively. E6 binds and induces ubiquitin-mediated degradation of p53, while E7 inactivates the Rb protein and alters additional cellular signaling pathways that are important for transformation. BBR can effectively target both the host AP1 and the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7. Inhibition of AP1 and blocking of viral E6 and E7 oncoprotein expression seem to be among the anti-HPV mechanisms of action of BBR [73].

Activity of BBR against members of the families Herpesviridae and Picornaviridae

Low (micromolar) concentrations of BBR can also suppress the replication of different HCMV strains that are resistant to known DNA polymerase inhibitors. HCMV is a member of the family Herpesviridae and has a dsDNA genome. HCMV is responsible for life-threatening pneumonia, gastrointestinal diseases, retinitis, and other conditions after primary infection and in immunocompromised patients. It also induces congenital defects in newborn infants, causing neurological disorders in approximately 0.1% of congenital infections. Lunganini et al. showed that BBR interferes with the transactivating function of the HCMV IE2 protein. IE2 plays a critical role in the progression of HCMV replication and in viral pathogenesis and reactivation from latency [74]. It is the most important HCMV regulatory protein and a strong transcriptional activator of viral and cellular gene expression. IE2 binds to DNA and has the ability to interact with cellular transcription factors, which is necessary for regulation of transcriptional activation of viral and host genes and cellular functions [75].

The inhibitory activity of BBR on the IE2-dependent transactivation of early genes depends on activation of MAPKs. BBR is active against human herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV 1 and 2) and also against mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV). HSV infection is characterized by small blisters on the skin or mucous membranes of the mouth, often called “cold sores” or “fever blisters”, and can cause a sore throat. It has been reported that BBR inhibits DNA synthesis by intercalating into DNA. BBR also inhibits the synthesis of both HSV-1 and HSV-2 late genes and proteins [76]. Inhibitory activity of BBR has also been observed against different genotypes of enterovirus 71 (EV71), which belongs to the family Picornaviridae and has a positive-sense RNA genome. This virus is the primary cause of hand, foot, and mouth disease, which spreads among infants and young children. Wang et al. showed that BBR and its derivatives (including a variety of esters and ethers at positions 3 and 9) (Table 1) exert moderate activity against EV71 replication. This is achieved mainly through downregulation of MEK/ERK signaling, inhibition of EV71-associated autophagy by activation of AKT, and suppression of the phosphorylation of JNK [77].

Anti-HIV activity

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is the causative agent of the worldwide acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic. Approximately 38 million people were estimated to live with HIV in 2018. Acute HIV infection often manifests clinically as a nonspecific viral infection syndrome with sore throat, fever, lymphadenopathy, or aseptic meningitis. HIV belongs to the family Retroviridae, subfamily Orthoretrovirinae.

The HIV genome consists of two identical single-stranded RNA molecules that are enclosed within the core of the virus particle. The virus has a very high genetic variability. The genome of the HIV provirus, also known as proviral DNA, is generated by reverse transcription of the viral RNA genome into DNA, degradation of the RNA, and integration of the double-stranded HIV DNA into the host genome. HIV is a retrovirus that occurs as two types: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV protease is an important enzyme for viral maturation. It cleaves Gag and the Gag-Pol polyprotein precursor at nine sites to produce mature active proteins. Therefore, HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) are used in highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) against HIV infection. However, some inhibitors induce expression of TNF-α and IL6, which are major mediators of the inflammatory response and are implicated in the pathogenesis of the variety of inflammatory diseases, including atherosclerosis [78]. BBR significantly inhibits HIV-PI-induced TNF-α and IL6 expression and ERK signaling [79].

BBR and berberrubine along with 9-substituted derivatives of berberine have demonstrated antiviral activity against HIV [80], probably due to inhibition of reverse transcriptase (RT) activity. The use of 20 µg of BBR per reaction resulted in 94% inhibition of HIV-1 RT. An improved therapeutic effect was observed when berberine-9-0 esters were used [80] (Table 1). BBR might therefore have a potential application as a complimentary therapeutic agent against HIV infection.

Conclusions

Recent studies have demonstrated therapeutic activity of BBR and its derivatives, especially against viral entry and replication. BBR has the ability to inhibit infection of various viruses including influenza virus, HSV, HCMV and CHIKV, and to reduce virus production. For some of these viral infections (e.g. CHIKV) there are still no approved drugs or treatments. Many viruses can target the MAPK pathway to manipulate cellular functions and control viral replication, leading to host cell death. These pathways are also involved in inhibitory effect of BBR. In addition, BBR can inhibit inflammatory responses triggered by viruses. Interestingly, in recent years, many scientific reports have reported immunostimulating and anti-inflammatory activity of BBR. Recent research suggests that BBR and its derivatives are active plant biomolecules that can be applied successfully for antiviral pharmacological strategies, possibly and hopefully also against SARS-CoV-2, which is currently a major problem worldwide.

References

Wang JT, Peng JG, Zhang JQ, Wang ZX, Zhang Y, Zhou XR, Miao J, Tang L (2019) Novel berberine-based derivatives with potent hypoglycemic activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 29(23):126709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.126709

Wang Y, Zidichowski JA (2018) Update on the benefits and mechanisms of action of the bioactive vegetal alkaloid berberine on lipid metabolism and homeostasis. Cholesterol. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7173920

Ma Y, Liang L, Zhang YB, Wag BF, Bai YG, Xie MJ, Wang ZW (2017) Berberine reduced blood pressure and improved vasolidation in diabetic rat. J Mol Endocrinol 59(3):191–204. https://doi.org/10.1530/JME-17-0014

Najaran H, Bafrani HH, Hamid Rashtbari H, Izadpanah F, Rajabi MR, Kashani HH, Mohammadi A (2019) Evaluation of the serum sex hormones levels and alkaline phosphatase activity in rats’ testis after administering of berberine in experimental varicocele. Orient Pharm Exp Med 19:157–165

Joshi PV, Shirkhedkar AA, Prakash K, Maheshwari VL (2011) Antidiarrheal activity, chemical and toxicity profile of Berberis aristata. Pharm Biol 49(1):94–100. https://doi.org/10.3109/13880209.2010.500295

DimitroviC R, Jakovac H, Blagojevic G (2011) Hepatoprotective activity of berberine is mediated by inhibition of TNF-α, COX-2, and iNOS expression in CCl4-intoxicated mice. Toxicology 280:33–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2010.11.005

Fan J, Li B, Ge T, Zhang Z, Lv J, Zhao J, Wang P, Liu W, Wang X, Mlyniec K, Cui B (2017) Berberine produces antidepressant-like effects in ovariectomized mice. Sci Rep 7:1310. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01035-5

Liu D, Memg X, Wu D, Qiu Z, Luo HA (2019) A natural isoquinoline alkaloid with antitumor activity: studies of the biological activities of berberine. Front Pharmacol 10:9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.00009

Peng L, Kang S, Yin Z, Jla R, Song X, Li Z, Zou Y, Liang X, Li L, He Ch, Ye G, Yin L, Shi F, Lv Ch, Jing B (2015) Antibacterial activity and mechanism of berberine against Streptococcus agalactiae. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 8(5):5217–5223

Galvez EM, Perez M, Domingo P, Nunez D, Cebolla VL, Matt M, Pardo J (2013) Pharmacological/biological effects of berberine. Nat Prod. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-22144-6_182

Pang YN, Liang YW, Feng TS, ZhaoS WuH, Chai YS, Lei F, Ding Y, Xing DM, Du LJ (2014) Transportation of berberine into HepG-2, Hela and SY5Y cells: a correlation to its ant-cancer effect. PLoS One 9(11):e112937. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112937

Fan J, Zhang K, Jin Y, Li B, Gao S, Zhu J, Cui R (2019) Pharmacological effects of berberine on mood disorders. J Cell Mol Med 23(1):21–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.13930

Cui HM, Zhang QY, Wang JL, Chen JL, Zhang YL, Tony XL (2014) In vitro studies of berberine metabolism and its effect of enzyme induction of HepG2 cells. J Ethnopharmacol 158:388–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.018

Guo Y, Pope C, Cheng XH, Zhon HH, Klaassen CD (2011) Dose-response of berberine on hepatic cytophromes P450 mRNA expression and activities in mice. J Ethnopharmacol 138(1):111–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2011.08.058

Cui HM, Zhang QY, Wang JL, Chen JL, Zhang YL, Tony XL (2014) In vitro studies of berberine metabolism and its effect of enzyme induction of HepG2 cells. J Ethnopharmacol 158:388–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.018

Song S, Quin M, Chu Y, Chen D, Su A, Wu Z (2014) Downregulation of cellular c-JUN N terminal protein kinase and NF-kB activation by berberine may result in inhibition of herpes simplex virus replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58(9):5068–5078. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02427-14

Keck F, Ataey P, Amaya M, Bailey C, Narayanan A (2015) Phosphorylation of single stranded RNA virus proteins and potential for novel therapeutic strategies. Viruses 7(10):5257–5273. https://doi.org/10.3390/v7102872

Adamson AL, Darr D, Holley-Guthrie E, Johnson RA, Mauser A, Swenson J, Kenney S (2000) Epstein–Barr virus immediate-early proteins BZLF1 and BRLF1 activate the ATF2 transcription factor by increasing the levels of phosphorylated p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinases. J Virol 74(3):1224–1233. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.74.3.1224-1233.2000

Erhardt A, Hassan M, Heintges T, Häussinger D (2002) Hepatitis C virus core protein induces cell proliferation and activates ERK, JNK, and p38 MAP kinases together with the MAP kinase phosphatase MKP-1 in a HepG2 Tet-Off cell line. Virology 292(2):272–284. https://doi.org/10.1006/viro.2001.1227

Fung TS, Liu DX (2017) Activation of the c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase pathway by coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus promotes apoptosis independently of c-Jun. Cell Death Dis 8(12):3215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-017-0053-0

Hemonnot B, Cartier C, Gay B, Rebuffat S, Bardy M, Devaux C, Boyer V, Briant L (2004) The host cell MAP kinase ERK-2 regulates viral assembly and release by phosphorylating the p6gag protein of HIV-1. J Biol Chem 279(31):32426–32434. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M313137200

Gaestel M (2015) MAPK-activated protein kinases (MKs): novel insights and challenges. Front Cell Dev Biol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2015.00088

Hoover HS, Kao CC (2016) Phosphorylation of the viral coat protein regulate RNA virus infection. Virus Adapt Treat 8:13–20. https://doi.org/10.2147/VAAT.S118440

Keating JA, Striker B (2012) Phosphorylation events during viral infection provide potential therapeutic target. Rev Med Virol 23(3):166–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.722

Nayak TK, Mamidi P, Sahoo SS, Kumar PS, Mahish C, Chatterjee S, Subudhi BB, Chattopadhyay S, Chattopadhyay S (2019) P38 and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases interact with chikungunya virus non-structural protein-2 and regulate TNF induction during viral infection in macrophages. Front Immunol 10:786. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00786

Varghese FS, Thaa B, Amrun SN, Simarmata D, Rausalu K, Nyman TA, Maerts A, Mcinerney GM, Ng LFP, Alola T (2016) The antiviral alkaloid berberine reduces chikungunya virus-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase signalig. J Virol 90(21):9743–9757. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01382-16

Nayak TK, Mamidi P, Sahoo SS, Kumar PS, Mahish CHH, Chatterjee S, Subudhi BB, Chattopadhyay S, Chattopadhyay S (2019) P38 and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases interact with Chikungunya virus non-structural protein-2 and regulate TNF induction during viral infection in macrophages. Front Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/Immun.2019.00786

Shin HB, Choi MS, Yi CM, Lee J, Kim NJ, Inn KS (2015) Inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus replication and virus-induced p38 kinase activity by berberine. Int Immunopharmacol 27(1):65–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2015.04.045

Marchant D, Singhera GK, Utokaparch S, Hackett TL, Boyd JH, Luo Z, Si X, Dorscheid DR, McManus BM, Hegele RG (2010) Toll-like receptor 4-mediated activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is a determinant of respiratory virus entry and tropism. J Virol 84(21):11359–11373. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00804-10

Kin SY, Kim H, Kim SW, Lee NR, Chm Yi, Heo J, Kim BJ, Kim NJ, Inn KS (2017) An effective antiviral approach targeting hepatitis B virus with NJK14047, a novel and selective biphenyl amide p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61(8):52–60. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00214-17

Ming M, Sinnett-Smith J, Soares HP, Young SH, Eibl G, Rozengurt E (2014) Dose-dependent AMPK-dependent and independent mechanisms of berberine and metformin inhibition of mTORC1, ERK, DNA synthesis and proliferation in pancreatic cancer cell. PLos One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0114573

Agnarelli A, Natali M, Garcia-Gil M, Pesi R, GraziaTozzi M, Ippolito Ch, Bernardini N, Vignali R, Batistoni R, Bianucci AM, Marracci S (2018) Cell-specific pattern of berberine pleiotropic effects on different human cell lines. Sci Rep 8:10599. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28952-3

Vletnick AJ, De Bruyne T, Apers S, Pieters LA (1998) Plant-derived leading compounds for chemotherapy of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Planta Med 64(2):97–109

Schmeller T, Lats-Bruning B, Wink M (1997) Biochemical activities of berberine, palmatine and sanguinarine mediating chemical defence against microorganisms and herbivores. Phytochemistry 44(2):257–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(96)00545-6

El-Serag HB (2012) Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 142:1264–1273. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061

Kim SY, Kim H, Kim SW, Lee NR, Yi CM, Heo J, Kim BJ, Kim NJ, Inn KS (2017) An effective antiviral approach targeting hepatitis B virus with NJK14047, a novel and selective biphenyl amide p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00214-17

Wei ZQ, Zhang YH, Ke CZ, Chen HX, Ren P, He YL, Hu P, Ma DQ, Luo J, Meng ZJ (2017) Curcumin inhibits hepatitis B virus infection by down-regulating cccDNA-bound histone acetylation. World J Gastroenterol 23(34):6252–6260. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i34.6252

Gane EJ (2017) Future ant-HBV strategies. Liver Int 37(1):40–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13304

Zhao L-J, Wang W, Ren H, Qi Z-T (2013) ERK signaling is triggered by hepatitis C virus E2 protein through DC-SIGn. Cell Stress Chaperones 18(4):495–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12192-013-0405-3

Streekanth GP, Yenchitsomanus PT, Limjindaporn T (2018) Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in the pathogenesis of dengue virus infection. Cell Signal 48:64–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.05.002

Fung S, Liu D-X (2017) Activation of the c-Jun NH2- terminal kinase pathway by coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus promote apoptosis independently of c-Jun. Cell Death Dis 8(12):3215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s414119-017-0053-0

Voss K, Amaya M, Mueller C, Roberts B, Kehn-Hall K, Bailey CH, Petricoin E III, Narayanan A (2014) Inhibition of host extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation decreases new world alphavirus multiplication in infected cell. Viology 4680:490–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2014.09.005

Shi W, Hou X, Peng H, Zhang L, Li Y, Gu Z, Jiang Q, Shi M, Ji Y, Jiang J (2014) Mer/ERK signaling patway is required for enterovirus 71 replication in immature dendric cells. Virol J 11:227. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-014-0227-7

Mohamud Y, Luo H (2019) The interwined life cycles of enterovirus and autophagy. Virulence 1:470–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2018.1551010

Huang SC, Chang CL, Wang PS, Tsai Y, Liu HS (2009) Enterovirus 71-induced autophagy detected in vitro and in vivo promotes viral replication. J Med Virol 81(7):1241–1252. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.21502

Wang H, Li K, Ma L, Wu S, Hu J, Yan H, Jiang J, Li H (2017) Berberine inhibits enterovirus 71 replication by downregulating the MEK/ERK signaling pathway and authophagy. Virol J 14:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-016-0674-4

Hung TCh, Jassey A, Liu CH, Lin CH, Wong AH, Wang SH, Wang JY, Yen MH, Lin LT (2019) Berberine inhibits hepatitis C virus entry by targeting the viral E2 glycoprotein. Phytomedicine 53:62–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2018.09.025

Douam F, Lavillette D, Cosset FL (2015) The mechanism of HCV entry into host cells. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 129:63–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pmbts.2014.10.003

Kim S, Ishida H, Yamane DY, Swinney DC, Foung S, Lemon SM (2013) Contrasting roles of mitogen-activated protein kinases in cellular entry and replication of hepatitis C virus: MKNK1 facilitates cell entry. J Virol 87(8):4214. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00954-12

Gubler DJ (1989) Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin Microbiol Rev 11(3):480–496

Costello A, Dua T, Dura P, Gulmezoglu M, Oladapo OT (2016) Defining the syndrome associated with congenital Zika virus infection. Bull World Health Organ 94(6):404A–406A. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.176990

Srivastava V (2018) Quinacrine and berberine as antiviral agents against dengue and Zika fever: in silico approach. Biostat Bioinform 1:12. https://doi.org/10.31031/QABB.2018.02000532

Liu W, Zhang X, Lin P, Shen X, Lan T, Li W, Ijang Q, Xie X, Huang H (2010) Effects of berberine on matrix accumulation and NF kappa B signal patway in alloxan-induces diabetic mice with renal injury. Eur J Pharmacol 638(1–3):150–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.04.033

Suryavanshi S, Kulkarni YA (2017) NF kB: a potential target in the management of vascular complication of diabetes. Front Pharmacol 8:798. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2017.00798

Kim HY, Shin HS, Park H, Kim YC, Yun YG, Park S, Shin HJ, Kim K (2007) In vitro inhibition of coronavirus replications by the traditionally used medicinal herbal extracts, Cimicifuga rhizoma, Meliae cortex, Coptidis rhizoma, and Phellodendron cortex. J Clin Virol 41(2):122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2007.10.011

Shinae HB, Choi MS, Yi CM, Lee J, Kim NJ, Inn KS (2015) Inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus replication and virus-induced p38 kinase activity by berberine. Int Immunopharmacol 27(1):65–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2015.04.045

Acosta PL, Caballero MT, Polach FP (2016) Brief history and characterization of enhanced respiratory syncytia virus disease. Clin Vaccine Immunol 13:189–195. https://doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00609-15

Li CL, Tan LH, Wang YF, Luo CHD, Chen HB, Lu Q, Li YC, Yang XB, Chen JN, Liu YH, Xie JH, Su ZR (2019) Comparison of anti-inflammatory effects of berberine, and its natural oxidative and reduced derivatives from Rhizoma Coptidis in vitro and in vivo. Phytomedicine 53:272–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2018.09.228

Hanssbro PM, Dua K (2020) Immunological axis of berberine in managing inflammation underlying chronic respiratory inflammatory diseases. Chem Biol Interact 317:1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2020.108947

Yan YQ, Fu YJ, Wu S, Qin HQ, Zhen X, Song BM, Weng YS, Wang PC, Chen XY, Jiang ZY (2018) Anti-influenza activity of berberine improves prognosis by reducing viral replication in mice. Phytother Res 32(12):2560–2567. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6196

Eyer L, Hruska K (2013) Antiviral agents targeting the influenza virus: a review and publication analysis. Vet Med 58(3):113–185. https://doi.org/10.17221/6746-VETMED

World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/flunet. Accessed 8 Feb 2020

Yan YQ, Fu YJ, Wu S, Qin HQ, Zhen X, Song BM, Weng YS, Wang PC, Chen XY, Jiang ZY (2018) Anti-influenza activity of berberine improves prognosis by reducing viral replication in mice. Phytother Res 32(12):2560–2567. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6196

Troy NM, Bosco A (2016) Respiratory viral infections and host responses; insights from genomics. Respir Res 17:156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-016-0474-9

Kim JH, Weeratunga P, Kim MS, Nikapitiya C, Lee BH, Uddin MB, Kim TH, Yoon JE, Park C, Ma JY, Kim H, Lee JS (2016) Inhibitory effects of an aqueous extract from Cortex Phellodendri on the growth and replication of broad-spectrum of viruses in vitro and in vivo. BMC Complement Altern Med 2(16):265. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-016-1206-x

Cecil CE, Davis JM, Cech NB, Laster NB (2011) Inhibition of H1N1 influenza A virus growth and induction of inflammatory mediators by the isoquinoline alkaloid berberine and extracts of goldenseal (Hydrastis Canadensis). Int Immunopharmacol 11:1706–1714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2011.06.002

Enkhtaivan G, Muthuraman P, Kim DH, Mistry B (2017) Discovery of berberine based derivatives as anti-influenza agent through blocking of neuraminidase. Bioorg Med Chem 25(20):5185–5193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2017.07.006

Li GX, Wang XM, Jiang T, Gong JF, Niu LY, Li N (2015) Berberine prevents intestinal mucosal barrier damage during early phase of sepsis in rat through the toll-like receptors signaling pathway. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 19(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2015.19.1.1

Zou K, Li Z, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Li B, Zhu W, Shi J, Jia Q, Li Y (2017) Advances in the study of berberine and its derivatives: a focus on anti-inflammatory and antitumor effects in the digestive system. Acta Pharmacol Sin 38:157–166. https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2016.125

Yan YQ, Fu YJ, Wu S, Qin HQ, Zhen X, Song BM, Weng YS, Wang PC, Chen XY, Jiang ZY (2018) Anti-influenza activity of berberine improves prognosis by reducing viral replication in mice. Phytother Res 32(12):2560–2567. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6196

Wang X, Feng S, Ding N, He Y, Li Ch, Li M, Ding X, Ding H, Li J, Wu J, Li Y (2018) Anti-inflammatory effects of berberine hydrochloride in LPS-induced murine model of mastitis. Based Complement Alternat Med. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5164314

Knollmann A, Ritschel B (2019) Current understanding of the molecular basis of venezuelan equine encephalitis virus phatogenesis and vaccine development. Viruses 11(2):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11020164

Mahata S, Bharti AC, Shukla S, Tyagi A, Husain SA, Das BC (2011) Berberine modulate AP-1 activity to suppress HPV transcription and downstream signaling to induce growth arrest and apoptosis in cervical cancer cells. Mol Cancer 10:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-10-39

Luiganini A, Mercorelli B, Messa L, Paul G, Gribaudo G, Loregian A (2019) The isoquinoline alkaloid berberine inhibits human cytomegalovirus replication by interfering with viral immediates Early-2 (IE2) protein transactivating activity. Antivir Res 164:52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.02.006

Pignoloni B, Fionda C, Dell’Oste V, Luganini A, Cippitelli M, Zingoni A, Landolfo S, Gribaudo G, Santoni A, Cerboni C (2016) Distinct roles for human cytomegalovirus immediate early proteins IE1 and IE2 in the transciptional regulation of MICA and PVR/CD155 expression. J Immunol 197(10):4066–4078. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1502527

Chin LW, Cheng UW, Lin SH, Lai YY, Lin LY, Cou MY, Chou MC, Yang CC (2010) Anti-herpes simplex virus effects of berberine from Coptidis rhizome, a major component of a Chinese herbal medicine, Chig-Wei-San. Arch Virol 155(12):1933–1941. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-010-0779-9

Wang YX, Yang L, Wang HQ, Zhao X-Q, Liu T, Li Y-H, Zeng Q-X, Li Y-H, Song D-Q (2018) Synthesis and evolution of berberine derivatives as a new class of antiviral agents against enterovirus 71 through the MER/ERk pathway and autophagy. Molecules 23:2084. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23082084

Zhou H, Jarujaron S, Gurley EC, Chen L, Ding H, Studer E, Pandak WM, Hu W, Zou T, Wang JY, Hylemon PB (2007) HIV protease inhibitors increase TNF- and IL-6 expression in macrophages: involvement of the RNA-binding protein. Atherosclerosis. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.04.008

Zha W, Liang G, Xiao J, Studer EJ, Hylemon PB, Pandak WM, Wang G, Li X, Zhou H (2010) Berberine inhibits HIV protease inhibitor-induced inflammatory response by modulating ER stress signaling pathways in murine macrophages. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009069

Bodiwala HS, Sabde S, Mitra D, Bhutani KK, Singh IP (2011) Synthesis of 9- substituted derivatives of berberine as anti-HIV agents. Eur J Med Chem 46(4):1045–1049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.01.016

Hayashi K, Minoda K, Nagaoka Y, Hayashi T, Uesato S (2007) Antiviral activity of berberine and related compounds against human cytomegalovirus. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 17(6):1562–1564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.12.085

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from Polish National Science Centre Grant no. 2012/05/N/NZ9/01337.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Carolina Scagnolari.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Warowicka, A., Nawrot, R. & Goździcka-Józefiak, A. Antiviral activity of berberine. Arch Virol 165, 1935–1945 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-020-04706-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-020-04706-3