Abstract

The polyomaviruses KI (KIPyV) and WU (WUPyV) have recently been discovered in specimens from patients with respiratory tract infections. To analyze the frequency and clinical impact in a cohort of pediatric patients in a German University Children’s Hospital. Nasopharyngeal aspirates or bronchoalveolar lavage specimens of 229 children with acute respiratory tract infection were screened for KIPyV and WUPyV using polymerase chain reaction-based methods. KIPyV was detected in 2 (0.9%) and WUPyV in 1 (0.4%) patients, without co-infections with other respiratory viruses but with co-detection of CMV, EBV and HHV 6 in one immunocompromised patient. Only a very small proportion (1.3%) of positive samples for KIPyV and WUPyV was documented in this study; the clinical relevance of these viruses remains unclear and requires further evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since 2001, an increasing number of “new” respiratory viruses have been detected in children with respiratory tract infection (RTI), including the human metapneumovirus (hMPV) and the human bocavirus (hBoV) [4, 15]. Recently, two novel polyomaviruses were detected from respiratory secretions. Allander et al. [3] discovered a previously unrecognized human polyomavirus in 6 (1%) of 637 nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPAs) and 1 (0.5%) of 192 fecal samples and proposed a new KI polyomavirus (KIPyV). The second newly identified polyomavirus was described by Gaynor et al. in respiratory samples from Brisbane, Australia, and St. Louis, USA. The authors amplified and cloned the genome of WU Polyomavirus (WUPyV) from NPA of a 3-year-old patient with pneumonia without detection of other respiratory pathogens. Screening of 2,135 patients with RTI yielded 43 additional positive patients [8]. Since the first description of KIPyV and WUPyV, a number of prevalence studies from various areas have been published, but until now, the clinical relevance for RTI in children remains an unresolved issue [1, 5, 10].

Objectives

In this study, we retrospectively investigated NPAs from children with acute RTI for the presence of KIPyV and WUPyV DNA. The major aim was to elucidate the frequency of the novel viruses and to identify cases that may be of clinical interest.

Study design

Nasopharyngeal aspirates or bronchoalveolar lavage specimens from 229 children admitted to the hospital with acute respiratory tract disease were sent to the Department of Virology at the University of Bonn between January 2006 and December 2007. Samples were aliquoted for preparation of DNA/RNA and stored at −80°C. The following clinical pictures and course were defined as acute respiratory tract disease: bronchitis, bronchiolitis, central pneumonia, lobar pneumonia. A lower respiratory tract infection was documented as pneumonia only if a chest X-ray had confirmed the clinical diagnosis.

All samples were prospectively examined for RSV, influenza viruses A and B, coronavirus NL63, HKU1, OC43, and 229E, rhinovirus, adenovirus, hMPV, and hBoV by antigen detection, PCR or RT-PCR, as described previously [14, 16].

DNA for PCR detection of KIPyV and WUPyV was prepared from nasopharyngeal aspirates by using a QIAmp Viral DNA Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions, for RNA virus detection, RNA was extracted using a QiAmp Viral RNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). PCR amplifications were performed in 50-μl reaction mixtures under the following conditions: 25 pmol of each primer, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 9.0), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Roche, Germany). Reactions were run in a Biometra T3000 thermocycler using a step cycle programme. After initial denaturation of DNA at 95°C for 3 min, 35 cycles were run: 95°C for 1 min, annealing temperature of 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min with a 5-min 72°C extension after the 35 cycles. A 10-μl aliquot from each reaction was run on a 2% NuSieve 3:1 electrophoresis-grade agarose gel (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine, USA) in 1× TAE buffer (0.04 mol/l Tris acetate, 0.001 mol/l EDTA) with ethidium bromide (0.5 g/ml) to visualize the amplified PCR products under UV illumination. Primer sequences were taken from the original descriptions of KIPyV and WUPyV [4, 8].

Procedures for avoiding contamination were strictly followed. DNA/RNA isolation, preparation of reaction mixtures, and amplification and analysis were physically separated and performed in three different rooms. Positive-displacement tips were used for all manipulations, and negative controls containing reaction mixtures without DNA were always done.

Results

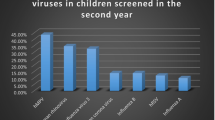

KIPyV and WUPyV DNA was detected in NPA specimens of 3 (1.3% of 229) patients (KIPyV n = 2; WUPyV n = 1), with co-detection of CMV, EBV and HHV 6 in one immunocompromised patient. Other common respiratory viruses were found in 39 children (RSV, n = 35; HMPV, n = 1; influenza A virus, n = 1; coronavirus, n = 1, hBoV, n = 1).

KIPyV case description 1

A 4-year-old girl was admitted to the hospital in November 2006 with fatigue, polydypsia, polyuria and anogenital candidiasis. A primary manifestation of diabetes type I was diagnosed, and insulin treatment was started immediately. The treatment was complicated by fever and signs of an acute RTI on day 3. No viral respiratory pathogens were detected in a nasopharygeal aspirate (except KIPyV, retrospectively). On day 12, the patient was discharged in good condition without further respiratory symptoms.

KIPyV case description 2

A 9-year-old girl with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia was admitted for bone marrow transplantation (BMT). Graft-versus-host prophylaxis was done with cyclosporine A and was switched to mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus because of suspected severe acute graft-versus-host disease of the skin and the gastrointestinal tract on day 20 after transplantation. Colonoscopy revealed Crohn-like-disease, and treatment with mesalazine, etanercept and cortisone was started. At day 37 (May 2006), the patient displayed respiratory distress; a chest X-ray examination showed left-sided basal pneumonia. Antimicrobial treatment including antifungals was started. In addition, ganciclovir was added because of the detection of cytomegalovirus, EBV and HHV-6 in a bronchoalveolar lavage specimen. The number of copies in quantitative DNA testing was found to be very low for all of these pathogens. No other respiratory viruses were detected (except KIPyV, retrospectively). Symptoms of the acute RTI improved during the following 20 days, and the patient was discharged from the hospital in good clinical condition 4 months after BMT.

WUPyV case description

A 2.5-year-old girl was admitted to the hospital in October 2006 because of acute bronchitis. No viral pathogens were detected in a nasopharygeal aspirate (except WUPyV, retrospectively). The patient received inhalative salbutamol, ipatropium bromide and budesonide as well as montelukast as oral medication. The patient was discharged on day 5 with salbutamol and montelukast continued.

Discussion

The very low prevalence of polyomavirus KI and WU DNA in NPA specimens of 3 out of 229 pediatric patients with acute RTI in this series does not confirm or exclude a pathogenic role of these newly described viruses. This, on the one hand, may be due to the relatively low sensitivity of our methods, which detected only 105 copies per ml NPA, but on the other hand, may also be caused by the lack of KIPyV and WUPyV in our patient cohort. Prevalence studies of KIPyV and WUPyV reported a worldwide distribution, with an incidence for KIPyV of 1% in Sweden, 1.4% in the UK, 2% in Thailand and 2.6% in Australia [4, 6, 7, 12, 13]. The prevalence of WUPyV was highest, with 7%, in South Korea and 6.3% Thailand [9, 13]. From Australia, the US and the UK, a prevalence of 4.5, 1.2 and 1.0%, respectively, has been reported [6, 8, 12]. The age distribution of KIPyV- and WUPyV-infected patients showed two peaks, with the highest rates in children under 5 years and in patients older than 45 years [2, 11]. A seasonal variation of KIPyV and WUPyV has not been consistently demonstrated. Most infections with KIPyV were detected during the winter months in Thailand, but not in a study conducted in Australia. In Australia, the incidence of WUPyV infections showed the highest peak in December; this was not confirmed in a study from Thailand [6, 7, 13].

The detection of KIPyV and WUPyV is frequently associated with co-infections with other respiratory viruses. High co-detection rates were found in Australia, with 75% for KIPyV, 80% for WUPyV; the most common co-pathogens were human rhinovirus and hBoV. Co-detection of KIPyV and WUPyV occurred in 14 patients, and only in one of these cases were no other respiratory virus present [6]. Norja et al. [12] detected KIPyV and WUPyV in 19 patients and viral co-infection in 10 patients, with predominant co-detection of adenovirus. The overall frequencies of detection of KIPyV and WUPyV were equal in patients with upper and lower respiratory tract infection, and in asymptomatic patients. Eight of the patients were immunocompromized [12].

In our study, we did not find co-infections with respiratory viruses in the three patients with KIPyV or WUPyV infection, and all patients had symptoms of ARTI. The clinical relevance of other viruses (CMV, EBV, HHV 6) co-detected in one severely immunocompromised patient in a bronchoalveolar lavage specimen is unclear. Nevertheless, coinfections still remain possible, as we were not able to test for all putative copathogens, and the amounts of viral nucleic acids present in the samples may have fallen below the detection limits for some pathogens. Hence, we carefully suggest that KIPyV and WUPyV are more than a viral colonization, with the limitation of our study being that we did not examine children without acute respiratory symptoms.

It is unknown whether KIPyV and WUPyV persist in the host and may be reactivated in cases of immunosuppression, similar to JCV and BKV. Furthermore, whether these viruses display an oncogenic potential, as described for other human and animal polyomaviruses, remains unclear and needs further evaluation [17].

However, Koch’s modified postulates have not yet been fulfilled, and so far, it is controversial whether KIPyV and WUPyV are indeed respiratory pathogens rather than innocent bystanders. Further studies are required to evaluate the clinical relevance of the detection of KIPyV and WUPyV in respiratory specimens.

References

Abed Y, Wang D, Boivin G (2007) WU polyomavirus in children, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis 13:1939–1941

Abedi Kiasari B, Vallely PJ, Corless CE, Al-Hammadi M, Klapper PE (2008) Age-related pattern of KI and WU polyomavirus infection. J Clin Virol 43:123–125

Allander T, Andreasson K, Gupta S, Bjerkner A, Bogdanovic G, Persson MA, Dalianis T, Ramqvist T, Andersson B (2007) Identification of a third human polyomavirus. J Virol 81:4130–4136

Allander T, Tammi MT, Eriksson M, Bjerkner A, Tiveljung-Lindell A, Andersson B (2005) Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:12891–12896

Babakir-Mina M, Ciccozzi M, Dimonte S, Farchi F, Valdarchi C, Rezza G, Perno CF, Ciotti M (2008) Identification of the novel KI polyomavirus in the respiratory tract of an Italian patient. J Med Virol 80:2012–2014

Bialasiewicz S, Whiley DM, Lambert SB, Jacob K, Bletchly C, Wang D, Nissen MD, Sloots TP (2008) Presence of the newly discovered human polyomaviruses KI and WU in Australian patients with acute respiratory tract infection. J Clin Virol 41:63–68

Bialasiewicz S, Whiley DM, Lambert SB, Wang D, Nissen MD, Sloots TP (2007) A newly reported human polyomavirus, KI virus, is present in the respiratory tract of Australian children. J Clin Virol 40:15–18

Gaynor AM, Nissen MD, Whiley DM, Mackay IM, Lambert SB, Wu G, Brennan DC, Storch GA, Sloots TP, Wang D (2007) Identification of a novel polyomavirus from patients with acute respiratory tract infections. PLoS Pathog 3:e64

Han TH, Chung JY, Koo JW, Kim SW, Hwang ES (2007) WU polyomavirus in children with acute lower respiratory tract infections, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis 13:1766–1768

Lin F, Zheng M, Li H, Zheng C, Li X, Rao G, Wu F, Zeng A (2008) WU polyomavirus in children with acute lower respiratory tract infections, China. J Clin Virol 42:94–102

Neske F, Blessing K, Ullrich F, Prottel A, Wolfgang Kreth H, Weissbrich B (2008) WU polyomavirus infection in children, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis 14:680–681

Norja P, Ubillos I, Templeton K, Simmonds P (2007) No evidence for an association between infections with WU and KI polyomaviruses and respiratory disease. J Clin Virol 40:307–311

Payungporn S, Chieochansin T, Thongmee C, Samransamruajkit R, Theamboolers A, Poovorawan Y (2008) Prevalence and molecular characterization of WU/KI polyomaviruses isolated from pediatric patients with respiratory disease in Thailand. Virus Res 135:230–236

Schildgen O, Glatzel T, Geikowski T, Scheibner B, Matz B, Bindl L, Born M, Viazov S, Wilkesmann A, Knopfle G, Roggendorf M, Simon A (2005) Human metapneumovirus RNA in encephalitis patient. Emerg Infect Dis 11:467–470

van den Hoogen BG, de Jong JC, Groen J, Kuiken T, de Groot R, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD (2001) A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat Med 7:719–724

Volz S, Schildgen O, Klinkenberg D, Ditt V, Muller A, Tillmann RL, Kupfer B, Bode U, Lentze MJ, Simon A (2007) Prospective study of human bocavirus (HBoV) infection in a pediatric university hospital in Germany 2005/2006. J Clin Virol 40:229–235

zur Hausen H (2008) Novel human polyomaviruses—re-emergence of a well known virus family as possible human carcinogens. Int J Cancer 123:247–250

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the European Commission (LSHM-CT-2006-037276).

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors reports any conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mueller, A., Simon, A., Gillen, J. et al. Polyomaviruses KI and WU in children with respiratory tract infection. Arch Virol 154, 1605–1608 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-009-0498-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-009-0498-2