Abstract

Background

The optimal management of clinoidal meningiomas (CMs) continues to be debated.

Methods

We constituted a task force comprising the members of the EANS skull base committee along with international experts to derive recommendations for the management of these tumors. The data from the literature along with contemporary practice patterns were discussed within the task force to generate consensual recommendations.

Results and conclusion

This article represents the consensus opinion of the task force regarding pre-operative evaluations, patient’s counselling, surgical classification, and optimal surgical strategy. Although this analysis yielded only Class B evidence and expert opinions, it should guide practitioners in the management of patients with clinoidal meningiomas and might form the basis for future clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Clinoidal meningiomas remain a challenging pathology because of their intimate relationship to vital neurovascular structures [43, 68]. Among skull base lesions, these are tumors that are still associated with high surgical morbidity and recurrence, next only to petroclival meningiomas [5]. Clinoidal meningiomas were clearly defined for the first time in 1938 by Cushing, who identified a distinct subgroup of medial third meningiomas from the larger cohort of sphenoidal ridge meningiomas [11]. These lesions account for less than half of sphenoidal ridge meningiomas and, based on their specific features (origin, dural attachment, growth pattern, neurovascular relationships) should be considered specific entities, distinct from spheno-cavernous meningiomas, though this distinction can occasionally be difficult [2, 74]. Pure clinoidal meningiomas have their epicenter on the anterior clinoid process (ACP) and tend to grow upward with a small pedicle toward the suprasellar area and the Sylvian fissure [55]. Their peculiar site of origin, inferolateral to the ACP and intimately related with the vessels supplying the optic apparatus, accounts for the poorer visual outcome and higher rate of subtotal resection (STR) compared with the more medially situated meningiomas (planum, diaphragma, and tuberculum meningiomas) [38]. Clinoidal meningiomas usually present with headache and visual disturbances but can become symptomatic with additional cranial neuropathies such as diplopia and facial hypoesthesia through cavernous sinus or superior orbital fissure invasion [19]. The main indication for surgery in these tumors is cranial neuropathy due to tumoral compression and/or radiological growth (in asymptomatic patients). Surgical management of clinoidal meningiomas differs largely between surgical series, primarily because they are often grouped with other sphenoid ridge meningiomas. The main aim of this consensus paper was to define the current optimal surgical management of pure clinoidal meningiomas.

Methods

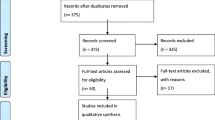

The EANS skull base section was created in October 2017, and its board decided to review the state of the art with respect to some controversial topics in the field, in order to generate recommendations from a European perspective. The optimal management of clinoidal meningiomas, especially the surgical strategy, continues to be debated. This work represents the consensually derived opinion and recommendations of the EANS skull base section board with the valuable participation of invited renowned experts in this field based on an earlier published systematic review and meta-analysis of studies in literature (Table 1), followed by formal discussions within the group [19]. The methods to identify, select, and critically appraise relevant research from previously published studies were detailed in our previous publication of the meta-analysis on clinoidal meningiomas [19]. Similar to the guidelines published by the EANS skull base section on other cranial base pathologies, the quality of evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group system [3]. If randomized blinded trials or prospective matched-pair cohort studies were identified, the recommendations were level A or B. For controlled non-randomized trials or uncontrolled studies, the recommendations were level C or “expert opinion,” respectively. The results of the meta-analysis and the systematic review of literature were discussed within the task force to generate recommendations in a consensual manner.

Radiological assessment

The literature supports the use of a complete preoperative neuro-radiological examination including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scan [5, 10, 12, 30, 37, 64, 70]. Preoperative CT can detect the presence of intratumoral calcifications, predicting a more firm and fibrous appearance at surgery. Bone CT can also add useful information about hyperostosis at the site of origin of the tumor that varies in extent from minimal to striking. Bone involvement is not predictive of tumor grade and can occur with both benign and malignant meningiomas [21]. In addition, it gives important information regarding the anatomy of the anterior clinoid process, its pneumatization, presence of a carotid-clinoid foramen, and surrounding bony structures. A contrast-enhanced MRI is now routinely performed to study tumor relationship with surrounding anatomical structures, optic canal and superior orbital fissure invasion, vascular encasement, and cavernous sinus invasion. Hyperintensity of the tumor in the T2-weighted image (T2W) is often associated with a soft consistency compared to hypointense tumors (on T2W imaging) that tends to be associated with more fibrous and firm tumors [79]. The dural vascular supply visible on T2W as a “sunburst” pattern can identify the vascular pedicle of the lesion. Gradient echo sequences (T2 GRE) are helpful to detect intratumoral calcification. MRI is also fundamental in evaluating tumor extensions to the cavernous sinus and optic canal. The constructive interference in steady state (CISS) sequence, a type of T2W gradient echo imaging, has been shown to be more effective than standard T1- and T2-weighted sequences in delineating key structures around the tumors and cerebrospinal fluid circumambient structures [26, 78]. The contrast-enhanced T1-weighted volume-interpolated breath-hold examination (VIBE) sequences have been shown to have a higher accuracy than standard sequences for predicting optic canal tumor extension with a good interrater agreement [7]. Volumetric tumor measurements are often of value to assess sequentially the indication for surgery in very small tumors and also to assess the efficacy of surgery and/or radiotherapy.

While conventional cerebral angiography can be performed in selected cases to detect major vessel encasement or displacement [5, 10, 20, 30, 37, 48, 63, 64], the same information may be obtained by less invasive radiological studies such as MR or CT angiography (MRA and CTA).The feeding arteries for clinoidal meningiomas usually come from dural branches of the internal carotid arteries or middle meningeal [62] and these lesions can be early devascularized by a skull base approach.

The literature supports the use of a complete preoperative neuro-radiological examination including MRI, CT scan, CTA, and/or MRA. High quality T2- and T1-imaging techniques (CISS and VIBE) may be used to increase visualization of tumor extension within the optic canal and cavernous sinus. In current practice, DSA may be considered in selected cases. (Level C).

Neuro-ophthalmological evaluation

The large majority of patients (> 60%) have visual acuity impairment at diagnosis [19], due to the intimate relationship of the tumor with the optic nerve. The most common symptom is a slowly progressing loss of monocular visual acuity (> 80% of cases) with more than two-thirds of patients presenting with already severely impaired vision. The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms are related to chronic ischemia in addition to the mechanical compression of the nerve. Preoperative visual status, duration of symptoms, lesion size, and adherence to internal carotid artery (ICA) and its branches have been shown to be significant determinants of postoperative visual outcome. Pooled rate of visual improvement after surgery for anterior clinoidal meningiomas is observed in less than half of patients (48%, 95% CI 38.6–57.4%)[19]. This outcome is worse compared to planum sphenoidale, tuberculum/diaphragma sellae meningiomas [18, 39, 47], probably due to the intimate relationship of the tumor with the vascularization of the optic nerve and the greater risks associated with intraoperative manipulation of the optic apparatus [56, 73]. Despite the fact that the rate of optic canal invasion is less than a third (20.9%) for clinoidal meningiomas [19], lesser than that for tuberculum/diaphragma meningiomas [18, 40, 53], the rate of visual improvement is inferior in clinoidal meningiomas, possibly attesting to the higher risk of ischemic involvement of the nerve in these tumors [52]. However, the incidence of the visual deterioration after surgery remains the same for both tumor groups (4.5%, 95% CI 3.0–6%), possibly related to the improved surgical approaches and techniques [19].

Considering the high rate of visual impairment, we recommend the use of a detailed neuro-ophthalmological examination including visual acuity, visual field examination, optic fundoscopy, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) before and usually 3 months after surgery (or earlier if there are new deficits). (Level C).

Surgical classification

Several classification schemes have been proposed as methods for predicting surgical outcome, though giant tumors of the clinoid process can often be challenging to classify due to the difficulty in differentiating the primary attachment from secondary extensions [2, 20, 49, 50, 55, 62, 63, 75]. Of these classifications, the Al-Mefty classification [2] has been widely accepted [9, 10, 19, 55, 60, 73]. This classification considers the tumor invasion pattern, according to its site of origin, as an indicator of resectability. It divides the ACMs into 3: group I for tumors arising proximal to the end of the carotid cistern, inferomedial surface of the ACP (no arachnoidal dissection plane between the ICA and tumor); group II for tumors arising distal to the segment of the carotid invested in the carotid cistern, arising from the lateral and superior surface of the ACP (which do have an arachnoidal plane between ICA and tumor; and group III, meningiomas that originate at the optic foramen. In group III tumors, the arachnoid membrane is present between the ICA and the tumor, but may be absent between the optic nerve and the tumor. Goel [20] and Nanda [50] proposed two similar scoring system based on anatomical, clinical, and radiological parameters. Nakamura et al. [49] divided ACMs in two groups based on cavernous sinus invasion. Pamir [55] modified the Al-Mefty classification, by adding the diameter of the tumor (< 2, 2–4, > 4 cm). These classifications based on a scoring system have the disadvantage of being complex and not user-friendly; moreover, their predictive value for tumor resectability and postoperative functional outcome has not yet been validated by larger studies. Despite the practical implication of the Al-Mefty classification with regard to surgical resectability, the distinction between the various groups is not always possible in the preoperative analysis, especially for large tumors. Nevertheless, our previous meta-analysis [19] showed that resection quality and gross total resection (GTR) rate are globally homogenous across the published studies for all Al-Mefty subgroups [19], proposing this classification for clinical and comparative use.

Can preoperative imaging differentiate between Al Mefty groups I and II?

The difficulty in surgically excising anterior clinoid meningiomas primarily stems from its relationship to the ipsilateral ICA and its branches especially in adventitial involvement in the absence of an arachnoidal plane. A classification system may be considered useful in surgical planning if can be reliably derived from the preoperative imaging. Several groups have analyzed preoperative radiological parameters in order to predict tumor resectability [1, 2, 5, 9, 10, 19, 20, 30, 34, 49, 50, 55, 60, 62,63,64,65, 70, 73, 75]. Nevertheless, the most modern magnetic resonance techniques and angiography do not allow, with sufficient sensitivity, the detection of an arachnoidal plane between the tumor and the artery. Most authors [9, 10, 55, 73] who adopted the Al-Mefty classification do not specify whether it is an intraoperative determination or a preoperative radiological classification. Some clearly admit that in large tumors, it is difficult to differentiate between groups I and II from preoperative images alone, and they have reclassified the lesion based on intraoperative evidence of vessel encasement [19, 60, 62].

Angiographic demonstration of direct arterial feeders from the carotid artery with narrowing of the ICA may point towards Al-Mefty Group I tumors, predicting difficulty in complete dissection off the artery. However,, a statistically significant correlation between the radiological findings and extent of resection has not been demonstrated [62]. When the ICA is encased greater than 180° and/or stenosed, the adventitia is more likely to be invaded [20, 49, 50, 63, 70]. However, Goel et al. [20] found that arterial narrowing appeared to be more related to the tumor consistency rather than invasion of the arachnoidal plane. In his original paper, Al-Mefty [2] found that an arachnoidal plane was absent only in less than 30% of the cases which had a total encased ICA. Similarly, Bassiouni et al. [5] showed that only in 11 out of 51 patients with a completely encased ICA was the tumor adherent to the vessel adventitia. Increasingly sophisticated MRI techniques, such as “high-resolution compressed-sensing T1 black-blood MRI,” offers promising potential in the context of neurovascular vessel wall imaging [23, 69, 77]. This sequence has been proven to assess extent of tumor and vessel lumen or wall infiltration, mostly for venous structures, by replacing and combining the information that were previously derived from two separate sequences 2D TOF (Time of Flight) magnetic resonance angiography and post-contrast 3D MPRAGE (Magnetization Prepared RApid Gradient Echo) T1 MRI [23]. Yin et al. demonstrated the ability of slip interface imaging (SII), a recently developed magnetic resonance elastography-based technique, to predict the degree of meningioma-brain adhesion and pial invasion, allowing for improved prediction of surgical risk and tumor resectability [80]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is presently no literature that assesses the sensitivity of these techniques in determining the presence of an arachnoidal plane between the tumor and the arterial wall.

The literature supports the use of anatomical classification when reporting the results of ACM surgery enabling comparison between series and different surgical approaches. The main factors determining quality of resection and postoperative complications seem to be the intimate relationship between the tumor and vessel adventitia and cavernous sinus invasion. Authors are encouraged to consider these details in tumor description. (Level C and Expert opinion).

Surgical technique

Preoperative embolization?

The utility of preoperative embolization remains controversial. There is paucity of data regarding the usefulness of preoperative embolization for clinoidal meningiomas. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis, performed by Ilyas et al. [27], showed that embolization was associated with a significant complication rate of 12% yet added no significant advantage in terms of quality of resection. Some authors have reported the use of preoperative embolization in selected cases of tumors having a significant external carotid artery supply [5, 62, 64].

“Vascular surgery” or “skull base” perspective?

Historically, two antithetical surgical techniques have been described for resection of an anterior clinoidal meningioma, namely, a “vascular surgery” and a “skull base” perspective. The vascular perspective consists of extensive dissection of the distal part of the Sylvian fissure to delineate and follow the middle cerebral artery toward the ICA [6]. The rationale is to keep the main artery under continuous vision while removing the tumor piecemeal, enabling safe dissection of the small perforators arising from the main arterial trunks. The main criticism of a vascular approach is that, in order to trace middle cerebral artery branches back to the main ICA trunk, the compressed Sylvian fissure needs to be opened and this carries a higher risk of stretching the arteries and of retraction injury to the brain [2]. Although some surgeons continue to use this technique, others favor a skull base approach with extensive epidural bone work along with an anterior clinoidectomy that has the advantage of expanding the surgical corridor with minimal brain retraction to achieve early optic nerve decompression and devascularization of the tumor at its dural origin [2, 34]. With this technique, the intraoperative and postoperative vascular complication rates were found to be 1.0% (95% CI, 0.4–1.6%; P. 0.960) and 1.9% (95% CI, 1.1–2.7%; P. 0.103), respectively, and new postoperative cranial nerve deficits were observed in only 5.5% of patients (95% CI, 3.6–7.5%). Mortality rate is also very low, estimated to be 1.2% (95% CI, 0.6–1.8%; P. 0.841) [19]. This technique is at present the most commonly used approach [19], and the different variants (standard pterional approach, fronto-orbito zygomatic approach, and suprabrow lateral subfrontal approach) can be tailored according to the anatomy and tumor size [19]. The extent of the Sylvian fissure opening and dissection will depend essentially on the encasement of the carotid artery bifurcation, A1 and M1 segments, and their branches.

Clinoidectomy or not?

Anterior clinoidectomy is now an integral part of the approach to the anterolateral skull base for the treatment of clinoid meningiomas, adding significant advantages including early devascularization of the meningioma, early optic nerve decompression, reducing manipulation of the visual pathway, and early identification of the ICA and optic nerve, reducing the possibility of injuring these structures [2, 15, 19, 34, 43, 66]. In addition, it could provide access to the clinoidal segment of the artery for proximal control in addition to increased access to remove tumors from the carotid cave.

An extradural anterior clinoidectomy (EAC) is the most common procedure in most published series [1, 2, 4, 10, 12, 19, 30, 34, 37, 42, 48, 62, 65, 68, 73, 75], and its variant, the intradural anterior clinoidectomy (IAC), has been performed in selected cases by a few authors [5, 49, 50, 55, 63, 64, 70]. EAC also allows the skeletonization of 270° of the optic canal allowing safer removal of the tumor in this region. Due to the lack of comparative studies and data in literature, a specific analysis of the impact of this technique on the functional outcome and the quality of surgical excision is not available [19]. The main concern with EAC lies in the supposed higher risk of vascular and nerve injuries, and the higher chances of CSF leak in case of ACP pneumatization [81]. The extended meta-analysis we previously published showed a rate of visual deterioration of 4–5%, similar between the series, regardless whether an EAC was performed or not, and previous analysis of the literature reported a lower risk of postoperative visual deterioration when an early optic nerve decompression was routinely performed [19]. The intraoperative vascular complication rates were found to be 1.0% (95% CI, 0.4–1.6%; P. 0.960) and is homogeneous among the published series regardless of the surgical technique performed. However, the rate of CSF leak with an AC (EAC or IAC) was reported in up to 8–9% of cases by few authors [2, 4, 62, 75]. Tayebi Meybodi et al. [72] proposed a 2-step hybrid technique combining the advantages of the extradural and intradural techniques while avoiding their disadvantages. The extradural phase allows early ON decompression; however, the drilling of the optic strut and removal of the tip of the ACP is performed intradurally under direct vision of the critical neurovascular structures. This technique brings considerable advantages in paraclinoidal aneurysm surgery, but needs to be evaluated on large series dealing with clinoidal meningiomas. The best surgical strategy that can maximize surgical resection and at the same time guarantee the best functional outcome is a matter of debate. Series supporting an extradural approach with clinoidectomy show visual improvements rates in the higher range of the pooled results [19]. However, this observation must be analyzed considering the initial clinical status of the population under examination. In support of this, the series of Al-Mefty et al. [2] and Verma et al. [75] largely differ, reporting a lower rate of visual improvement; however, they reported a higher percentage of patients already blind (15% in the series of Verma et al.) or with long-lasting severe visual deficit (32%) [75]. In their series, Pamir et al. [55] reported excellent results in terms of vision improvement without performing an AC. The limitations of any form of clinoidectomy are the extra time required for the approach along with the specific expertise necessary.

Gross total resection (GTR) in case of Al-Mefty group 1 meningioma?

The reported outcome and GTR rate vary largely among the surgical series and the existing discrepancies may be explained by the different percentages of tumors with an infraclinoid origin (Al-Mefty group I) and cavernous sinus invasion. Pooled overall GTR of the published series is achieved in 64.2% of patient (95% CI, 57.3–71%), with a large deviation of the series at both ends of the distribution [19]. This wide divergence probably reflects the heterogeneity of the various cohorts of patients in terms of cavernous sinus (CS) invasion and tumor origin. The series reporting the higher rate of GTR [2, 34, 37, 42, 55, 65] often include only a minor percentage of Al-Mefty group I tumors or those with CS invasion when compared to series with lower reported rate of GTR [4, 68]. To corroborate these data, it is of considerable interest to note that GTR rates are globally homogeneous across studies for all Al-Mefty subgroups [19]. Notably, pooled GTR is achieved in 11.8% of patient in group I (95% CI, 2.4–21.1%) and this confirms the fact that GTR is seldom achievable in cases of an infraclinoid origin of the tumor [19].

GTR or STR in tumors with cavernous sinus invasion?

The ideal treatment for meningiomas is total surgical excision [25]. However, GTR is not always feasible in the cranial base [45], particularly for lesions invading the CS. CS involvement, found in 1/3 of clinoidal meningiomas, is one of the main factors limiting the extent of resection. Most series on meningeal lesions involving the CS report a recurrence rate of about 60% with a subtotal resection as compared to a rate of about 5–10% in cases of total resection [16]. Despite the microsurgical achievements which followed pioneering microanatomical studies of Dolenc in the 1980s, gross total resection of tumors invading the CS is associated with a high rate (33%) of postoperative neurological deficits and mortality [14, 16, 54, 58]. Authors that report resection of the intracavernous portion of the lesion [49, 60, 62], specifically do so in cases of soft lesions. However, despite this more aggressive approach, not only are the GTR rates (42–58.9%) similar or lower than the GTR reported in series adopting a conservative strategy (64.2%) [19] but the tumor recurrence rates are only between 5 and 15% [14, 29, 60, 62], similar to the pooled average rate of recurrence found in the literature (8.9%, 95% CI, 6–11.8%, with a mean weighted follow-up of 48.1 months) [19]. To reduce the post-therapeutic neurological deficits, recent recommendations for lesions invading the CS advocate combined treatment, relying on planned subtotal resection (without intracavernous dissection and tumor removal), and adjuvant stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) on the intracavernous residual tumor [16, 22, 36].

Tumor consistency affecting the GTR rate

Tumor consistency is a well-known determinant of a GTR in meningioma surgery. This assumes an important role for surgery in clinoidal meningiomas, where this factor has a large effect on resectability due to the intimate relationship of the tumor to the carotid artery, their branches, and the optic nerve. Tumors that are predominantly fibrotic and/or calcified thereby pose a significant surgical challenge and could easily be the determining factor for a subtotal resection [28].

Chiasmopexy or not?

The residual tumor that is left within the CS is anatomically close to the cisternal and foraminal segment of the optic nerve. With time, the distance that it is created at surgery between the residual tumor and the ON can be lost since the nerve tends to move back to its normal position. The proximity to the optic apparatus and the risk of radiation-induced optic neuropathy often prevents many surgeons from proposing SRS [13]. In addition, discriminating clear tumor margins from the visual apparatus is often challenging [46]. A simple technical solution is to place a fat graft between the ON and the tumor to maintain the distance gained at surgery and facilitates the identification of anatomic structures. This minimum safety distance created reduces the dose received by the optic nerve below 8 Gy [19]. Avoiding an oversized graft is recommended to avoid iatrogenic compression[67]. Transsphenoidal chiasmopexy has been successful reported in reversing visual degradation in cases of empty sella syndrome following treatment of pituitary tumors [24, 82] and has been used to increase the distance between the normal pituitary gland and the residual tumor, facilitating combined treatment with SRS or radiotherapy and effectively reducing the incidence of radiation injury to the normal pituitary gland [71]. However, no current consensus exists on the advantages of this technique in clinoidal meningioma surgery and its implications on the methods and timing of SRS.

Preoperative embolization is not indicated since a skull base approach allows early identification and devascularization of the meningioma. (Level C)

The literature supports the use of a skull base approach with clinoidectomy with the rationale of reducing brain retraction, avoiding complications related to a large opening of the Sylvian fissure, and performing an early devascularization of the tumor and early decompression of the involved optic nerve. The extent of the approach can be tailored on the tumor size anatomy and size. (Level C).

Attempts at microsurgical resection of the cavernous sinus involvement are not recommended and is not justified if the resection cannot be performed without compromising the function of the cranial nerves. (Level C).

Upfront radiosurgery for tumor residue

Though upfront SRS provides high local tumor control small clinoidal meningiomas without extensions to the optic foramen (level III evidence) [35], larger tumors with ON contact are seldom good candidates for SRS. However, SRS represents an efficient manner to treat CS tumor extensions following surgery for the clinoid meningiomas. The efficiency of this treatment can be extrapolated from results obtained following SRS for pure cavernous sinus meningiomas. A recent report provided long-term follow-up for cavernous sinus meningiomas following SRS and showed that 61% of patients had tumor regression, 2% were unchanged, and 15% increased, after a follow-up period of 101 months after SRS [57]. Actuarial tumor control rates after upfront SRS were 98%, 93%, 85%, and 85% at the 1, 5, 10, and 15 years, respectively. Fifteen (7.5%) patients experienced permanent cranial nerve deficits without evidence of tumor progression at a median onset of 9 months (2.3–85 months). It is now well acknowledged that marginal dose prescription ranges between 12 and 15 Gy, as no improvement of local control is achieved using more than 15 Gy [31]. One of the challenges for single fraction SRS remains the anatomical location, especially the proximity of the optic pathways. SRS and particularly Gamma Knife (GK, Elekta Instruments, AB, Sweden) can address this issue, due to its very steep gradient, provided there is no contact between the lesion and the optic apparatus. In fact, a distance of 2 to 4 mm between the optic apparatus and the tumor is enough to avoid delivering more than 8 to 10 Gy to the former, while recent studies have shown that such maximal dose can be safely increased up to 12 Gy [33]. Another challenge is related to the eventual post-SRS pituitary insufficiency. It has been advocated that a ratio of stalk-to-gland radiation dose of 0.8 or more significantly increased the risk of endocrinopathy following SRS [59]. For larger tumors with major comorbidities precluding surgical resection, hypofractionated radiosurgery (HRS) (usually 25 Gy in 3 to 5 fractions) can be used even when there is close contact or when encircling the optic apparatus [41]. Fariselli et al. [41] used CyberKnife for HRS and reported high local control rates, 93% at 5 years, while avoiding radiation-induced optic neuropathy (5.1% of visual worsening). In a recent systematic review on the role of SRS and fractionated radiotherapy (FRT) in cavernous sinus meningiomas [36], local progression-free survival at 5 years after GKS, Linac SRS, and FRT were, respectively, of 93.6%, 95.6%, and 97.4% (p > 0.05). Progression-free survival at 10 years in this study with these techniques were 82.3%, 87.4%, and 95.5%, respectively. Nevertheless, monofractionated treatments (GKS and Linac RS) induced more tumor volume regression than FRT, SRS achieving a twice-higher rate of tumor volume regression than FRT [36].

SRS represents an excellent method of treatment of residual tumor with the cavernous sinus following surgery for clinoidal meningiomas as it avoids the morbidity of intracavernous sinus surgery. (Level B).

SRS for small tumors or HRS/FRT for larger tumors can be considered as upfront alternative management for patients deemed unfit for surgery. (Level C)

Quality of life (QoL) and visual quality of life

The visual-related quality of life (VRQOL) needs to be analyzed separately from other neurological functional outcomes in clinoidal meningiomas, in order to assess the impact that visual impairment has on quality of life. Of the several evaluation instruments to assess VRQOL instruments proposed in literature [32], the Vision Core Measure1 (VCM1), a 10-item self-complete scale, has been proven to be an easy applicable and useful tool to the patient’s global feelings and perceptions associated with visual impairment [17]. Vu et al. [76] clearly found that non-correctable unilateral vision loss is associated with issues of safety and independent living with significantly poorer general health scores than those with normal vision in the dimensions of ‘‘social functioning’’ and ‘‘role limitation due to emotional problems’’ [44, 76]. Neil-Dwyer et al. [51] tried to correlate the disability after skull base surgery and the burden on care givers. They concluded that the most used outcome neurological scores (Glasgow Outcome Score, 36 item short-form health survey, modified Rankin scale, etc.) do not take into account more parameters such as vocational capacity, mobility, and quality of life and they might not be adequate for patients with visual disability [44, 51, 61]. Similarly, less attention has been paid to the effect that visual disability has upon patient’s career and employment [61]. Bor-Shavit et al. [8] examined the postoperative visual outcome in skull base meningiomas close to the optical pathway and found that, regardless of the cause or origin of the disability, a visual impairment in patients who are unilaterally blind or unable to drive has a major impact on the patient’s VRQOL. Unilateral impairment of VRQOL is strongly associated with impaired distant, near, and stereo vision, and equally has important vocational and occupational implications. Vision disability in working age adults confers important adverse consequences for the “health and wealth” of the patient and this should be given a priority higher than usually accorded [44, 61].

Visual quality of life is of primary concern in clinoidal meningioma surgery and should be given a higher priority. Patients should be counselled on the potential visual functional outcomes, including a discussion on the possibility of visual deterioration. Evaluation of the health-related quality of life represents a recommended requirement in the management of patients with a clinoidal meningioma and should be assessed before and after treatment. (Expert opinion).

Summary of recommendations

-

We recommend the use of a complete preoperative neuro-radiological examination including MRI, CT scan, CTA, and/or MRA. High-quality T2- and high-resolution T1-imaging techniques (CISS and VIBE) may be used to increase detection of tumor extension into the optic canal and cavernous sinus. (Level C)

-

We recommend the use of a detailed neuro-ophthalmological examination including visual acuity, visual field examination, optic fundoscopy and optical coherence tomography (OCT) before and usually 3 months after surgery (or earlier if there are new deficits). (Level C)

-

We recommend assessing health-related QoL and VRQoL before and after treatment. (Expert opinion

-

Patients should be counselled on the potential visual functional outcomes, including a discussion on the possibility of visual deterioration.

-

We recommend the use of intraoperative anatomical classification when reporting the results of clinoidal meningioma surgery. Authors are encouraged to consider the relationship between the tumor and vessel adventitia and cavernous sinus invasion in describing the tumor (Level C and Expert opinion)

-

Preoperative embolization is not indicated since a skull base approach allows early identification and devascularization of the meningioma. (Level C)

-

We recommend the use of a skull base approach with clinoidectomy as a general rule with the rationale of reducing brain retraction, avoid complications related to a large opening of Sylvian fissure, and performing an early devascularization of the tumor and early decompression of the involved optic nerve. The extent of the skull base approach can be tailored based on the tumor anatomy and size (Level C)

-

In the absence of an arachnoidal dissection plane between the tumor and the arterial wall (Al-Mefty Group I tumors), a GTR may not be achieved and a STR is recommended. (Level C)

-

Attempts at microsurgical resection of the cavernous sinus extension are not recommended. (Level C)

-

SRS for residual tumor within the cavernous sinus following surgery for clinoidal meningiomas represents an excellent method of treatment (Level B). FRT and HRT can be considered when the residual tumor maintains too small a distance from the optic nerve (level C).

Change history

07 November 2021

Updated due to the missing funding information.

References

Alam S, Chaurasia BK, Shalike N, Uddin A, Chowdhury D, Khan AH, Ansari A, Barua KK, Majumder MR (2018) Surgical management of clinoidal meningiomas: 10 cases analysis. Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 5

Al-Mefty O (1990) Clinoidal meningiomas. J Neurosurg 73:840–849. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1990.73.6.0840s

Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Harbour RT, Haugh MC, Henry D, Hill S, Jaeschke R, Leng G, Liberati A, Magrini N, Mason J, Middleton P, Mrukowicz J, O’Connell D, Oxman AD, Phillips B, Schunemann HJ, Edejer T, Varonen H, Vist GE, Williams JW Jr, Zaza S, Group GW (2004) Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 328:1490. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490

Attia M, Umansky F, Paldor I, Dotan S, Shoshan Y, Spektor S (2012) Giant anterior clinoidal meningiomas: surgical technique and outcomes. J Neurosurg 117:654–665. https://doi.org/10.3171/2012.7.JNS111675

Bassiouni H, Asgari S, Sandalcioglu IE, Seifert V, Stolke D, Marquardt G (2009) Anterior clinoidal meningiomas: functional outcome after microsurgical resection in a consecutive series of 106 patients Clinical article. J Neurosurg 111:1078–1090. https://doi.org/10.3171/2009.3.17685

Bonnal J, Thibaut A, Brotchi J, Born J (1980) Invading meningiomas of the sphenoid ridge. J Neurosurg 53:587–599. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1980.53.5.0587

Borghei-Razavi H, Lee J, Ibrahim B, Muhsen BA, Raghavan A, Wu I, Poturalski M, Stock S, Karakasis C, Adada B, Kshettry V, Recinos P (2021) Accuracy and interrater reliability of CISS versus contrast-enhanced T1-weighted VIBE for the presence of optic canal invasion in tuberculum sellae meningiomas. World Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2021.01.015

Bor-Shavit E, Hammel N, Nahum Y, Rappaport ZH, Stiebel-Kalish H (2015) Visual disability rates in a ten-year cohort of patients with anterior visual pathway meningiomas. Disabil Rehabil 37:958–962. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.948141

Chernov SV, Rzaev DA, Kalinovsky AV, Dmitriev AB, Kasymov AR, Zotov AV, Gormolysova EV, Uzhakova EK (2017) Early postoperative results of surgical treatment of patients with anterior clinoidal meningiomas. Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko 81:74–80. https://doi.org/10.17116/neiro201780774-80

Cui H, Wang Y, Yin YH, Fei ZM, Luo QZ, Jiang JY (2007) Surgical management of anterior clinoidal meningiomas: a 26-case report. Surg Neurol 68(Suppl 2):S6–S10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surneu.2007.09.013. discussion S10

Cushing HEL (1938) Meningiomas: Their Classification, Regional Behavior, Life History, and Surgical End Results

Czernicki T, Kunert P, Nowak A, Marchel A (2015) Results of surgical treatment of anterior clinoidal meningiomas - our experiences. Neurol Neurochir Pol 49:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pjnns.2015.01.003

Danesh-Meyer HV (2008) Radiation-induced optic neuropathy. J Clin Neurosci 15:95–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2007.09.004

DeMonte F, Smith HK, al-Mefty O (1994) Outcome of aggressive removal of cavernous sinus meningiomas. J Neurosurg 81:245–251. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1994.81.2.0245

Dolenc VV (1985) A combined epi- and subdural direct approach to carotid-ophthalmic artery aneurysms. J Neurosurg 62:667–672. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1985.62.5.0667

Dufour H, Muracciole X, Metellus P, Regis J, Chinot O, Grisoli F (2001) Long-term tumor control and functional outcome in patients with cavernous sinus meningiomas treated by radiotherapy with or without previous surgery: is there an alternative to aggressive tumor removal? Neurosurgery 48:285–294. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006123-200102000-00006. discussion 294-286

Frost NA, Sparrow JM, Durant JS, Donovan JL, Peters TJ, Brookes ST (1998) Development of a questionnaire for measurement of vision-related quality of life. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 5:185–210. https://doi.org/10.1076/opep.5.4.185.4191

Giammattei L, Starnoni D, Cossu G, Bruneau M, Cavallo LM, Cappabianca P, Meling TR, Jouanneau E, Schaller K, Benes V, Froelich S, Berhouma M, Messerer M, Daniel RT (2020) Surgical management of tuberculum sellae meningiomas: myths, facts, and controversies. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 162:631–640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-019-04114-w

Giammattei L, Starnoni D, Levivier M, Messerer M, Daniel RT (2019) Surgery for clinoidal meningiomas: case series and meta-analysis of outcomes and complications. World Neurosurg 129:e700–e717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.05.253

Goel A, Gupta S, Desai K (2000) New grading system to predict resectability of anterior clinoid meningiomas. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 40:610–616. discussion 616-617

Gokce E, Beyhan M, Acu L (2020) Cranial Intraosseous Meningiomas: CT and MRI Findings. Turk Neurosurg 30:542–549. https://doi.org/10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.25694-18.4

Goldbrunner R, Minniti G, Preusser M, Jenkinson MD, Sallabanda K, Houdart E, von Deimling A, Stavrinou P, Lefranc F, Lund-Johansen M, Moyal EC, Brandsma D, Henriksson R, Soffietti R, Weller M (2016) EANO guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of meningiomas. Lancet Oncol 17:e383-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30321-7

Guggenberger K, Krafft AJ, Ludwig U, Vogel P, Elsheik S, Raithel E, Forman C, Dovi-Akue P, Urbach H, Bley T, Meckel S (2019) High-resolution compressed-sensing T1 black-blood MRI: a new multipurpose sequence in vascular neuroimaging? Clin Neuroradiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00062-019-00867-0

Hamlyn PJ, Baer R, Afshar F (1988) Transsphenoidal chiasmopexy for long standing visual failure in the secondary empty sella syndrome. Br J Neurosurg 2:277–279. https://doi.org/10.3109/02688698808992681

Hasseleid BF, Meling TR, Ronning P, Scheie D, Helseth E (2012) Surgery for convexity meningioma: Simpson Grade I resection as the goal: clinical article. J Neurosurg 117:999–1006. https://doi.org/10.3171/2012.9.JNS12294

Hingwala D, Chatterjee S, Kesavadas C, Thomas B, Kapilamoorthy TR (2011) Applications of 3D CISS sequence for problem solving in neuroimaging. Indian J Radiol Imaging 21:90–97. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-3026.82283

Ilyas A, Przybylowski C, Chen CJ, Ding D, Foreman PM, Buell TJ, Taylor DG, Kalani MY, Park MS (2019) Preoperative embolization of skull base meningiomas: a systematic review. J Clin Neurosci 59:259–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2018.06.022

Itamura K, Chang KE, Lucas J, Donoho DA, Giannotta S, Zada G (2018) Prospective clinical validation of a meningioma consistency grading scheme: association with surgical outcomes and extent of tumor resection. J Neurosurg 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.7.JNS1838

De Jesus O, Sekhar LN, Parikh HK, Wright DC, Wagner DP (1996) Long-term follow-up of patients with meningiomas involving the cavernous sinus: recurrence, progression, and quality of life. Neurosurgery 39:915–919. discussion 919-920

Kim JH, Jang WY, Jung TY, Kim IY, Lee KH, Kang WD, Kim SK, Moon KS, Jung S (2017) Predictive factors for surgical outcome in anterior clinoidal meningiomas: Analysis of 59 consecutive surgically treated cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 96:e6594. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000006594

Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC, Perez B (1998) Judicious resection and/or radiosurgery for parasagittal meningiomas: outcomes from a multicenter review. Gamma Knife Meningioma Study Group. Neurosurgery 43:405–413. discussion 413-404

Lamoureux EL, Pesudovs K, Pallant JF, Rees G, Hassell JB, Caudle LE, Keeffe JE (2008) An evaluation of the 10-item vision core measure 1 (VCM1) scale (the Core Module of the Vision-Related Quality of Life scale) using Rasch analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 15:224–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09286580802256559

Leavitt JA, Stafford SL, Link MJ, Pollock BE (2013) Long-term evaluation of radiation-induced optic neuropathy after single-fraction stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 87:524–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.06.2047

Lee JH, Jeun SS, Evans J, Kosmorsky G (2001) Surgical management of clinoidal meningiomas. Neurosurgery 48:1012–1019. discussion 1019-1021

Lee CC, Trifiletti DM, Sahgal A, DeSalles A, Fariselli L, Hayashi M, Levivier M, Ma L, Alvarez RM, Paddick I, Regis J, Ryu S, Slotman B, Sheehan J (2018) Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Benign (World Health Organization Grade I) Cavernous Sinus Meningiomas-International Stereotactic Radiosurgery Society (ISRS) Practice Guideline: A Systematic Review. Neurosurgery 83:1128–1142. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyy009

Leroy HA, Tuleasca C, Reyns N, Levivier M (2018) Radiosurgery and fractionated radiotherapy for cavernous sinus meningioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 160:2367–2378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-018-3711-9

Liu DY, Yuan XR, Liu Q, Jiang XJ, Jiang WX, Peng ZF, Ding XP, Luo DW, Yuan J (2012) Large medial sphenoid wing meningiomas: long-term outcome and correlation with tumor size after microsurgical treatment in 127 consecutive cases. Turk Neurosurg 22:547–557. https://doi.org/10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.5142-11.1

Lu VM, Goyal A, Rovin RA (2018) Olfactory groove and tuberculum sellae meningioma resection by endoscopic endonasal approach versus transcranial approach: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 174:13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2018.08.029

Magill ST, Morshed RA, Lucas CG, Aghi MK, Theodosopoulos PV, Berger MS, de Divitiis O, Solari D, Cappabianca P, Cavallo LM, McDermott MW (2018) Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: grading scale to assess surgical outcomes using the transcranial versus transsphenoidal approach. Neurosurg Focus 44:E9. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.1.FOCUS17753

Mahmoud M, Nader R, Al-Mefty O (2010) Optic canal involvement in tuberculum sellae meningiomas: influence on approach, recurrence, and visual recovery. Neurosurgery 67:ons108-118. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000383153.75695.24. discussion ons118-109

Marchetti M, Bianchi S, Pinzi V, Tramacere I, Fumagalli ML, Milanesi IM, Ferroli P, Franzini A, Saini M, DiMeco F, Fariselli L (2016) Multisession Radiosurgery for Sellar and Parasellar Benign Meningiomas: Long-term Tumor Growth Control and Visual Outcome. Neurosurgery 78:638–646. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000001073

Mariniello G, de Divitiis O, Bonavolonta G, Maiuri F (2013) Surgical unroofing of the optic canal and visual outcome in basal meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 155:77–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-012-1485-z

Mathiesen T, Lindquist C, Kihlstrom L, Karlsson B (1996) Recurrence of cranial base meningiomas. Neurosurgery 39:2–7. discussion 8-9

McKean-Cowdin R, Varma R, Wu J, Hays RD, Azen SP, Los Angeles Latino Eye Study G (2007) Severity of visual field loss and health-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol 143:1013–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2007.02.022

Meling TR, Da Broi M, Scheie D, Helseth E (2019) Meningiomas: skull base versus non-skull base. Neurosurg Rev 42:163–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-018-0976-7

Minniti G, Scaringi C, Clarke E, Valeriani M, Osti M, Enrici RM (2011) Frameless linac-based stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) for brain metastases: analysis of patient repositioning using a mask fixation system and clinical outcomes. Radiat Oncol 6:158. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-6-158

Mortazavi MM, Brito da Silva H, Ferreira M Jr, Barber JK, Pridgeon JS, Sekhar LN (2016) Planum sphenoidale and tuberculum sellae meningiomas: operative nuances of a modern surgical technique with outcome and proposal of a new classification system. World Neurosurg 86:270–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.09.043

Nagata T, Ishibashi K, Metwally H, Morisako H, Chokyu I, Ichinose T, Goto T, Takami T, Tsuyuguchi N, Ohata K (2013) Analysis of venous drainage from sylvian veins in clinoidal meningiomas. World Neurosurg 79:116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2011.05.022

Nakamura M, Roser F, Jacobs C, Vorkapic P, Samii M (2006) Medial sphenoid wing meningiomas: clinical outcome and recurrence rate. Neurosurgery 58:626–639. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000197104.78684.5D. discussion 626-639

Nanda A, Konar SK, Maiti TK, Bir SC, Guthikonda B (2016) Stratification of predictive factors to assess resectability and surgical outcome in clinoidal meningioma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 142:31–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.01.005

Neil-Dwyer G, Lang D, Garfield J (2001) The realities of postoperative disability and the carer’s burden. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 83:215–218

Nimmannitya P, Goto T, Terakawa Y, Sato H, Kawashima T, Morisako H, Ohata K (2016) Characteristic of optic canal invasion in 31 consecutive cases with tuberculum sellae meningioma. Neurosurg Rev 39:691–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-016-0735-6

Nozaki K, Kikuta K, Takagi Y, Mineharu Y, Takahashi JA, Hashimoto N (2008) Effect of early optic canal unroofing on the outcome of visual functions in surgery for meningiomas of the tuberculum sellae and planum sphenoidale. Neurosurgery 62:839–844. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000318169.75095.cb. discussion 844-836

O’Sullivan MG, van Loveren HR, Tew JM Jr (1997) The surgical resectability of meningiomas of the cavernous sinus. Neurosurgery 40:238–244. discussion 245-237

Pamir MN, Belirgen M, Ozduman K, Kilic T, Ozek M (2008) Anterior clinoidal meningiomas: analysis of 43 consecutive surgically treated cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 150:625–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-008-1594-x. discussion 635-626

Park CK, Jung HW, Yang SY, Seol HJ, Paek SH, Kim DG (2006) Surgically treated tuberculum sellae and diaphragm sellae meningiomas: the importance of short-term visual outcome. Neurosurgery 59:238–243. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000223341.08402.C5. discussion 238-243

Park KJ, Kano H, Iyer A, Liu X, Tonetti DA, Lehocky C, Faramand A, Niranjan A, Flickinger JC, Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD (2018) Gamma Knife stereotactic radiosurgery for cavernous sinus meningioma: long-term follow-up in 200 patients. J Neurosurg 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.2.JNS172361

Pichierri A, Santoro A, Raco A, Paolini S, Cantore G, Delfini R (2009) Cavernous sinus meningiomas: retrospective analysis and proposal of a treatment algorithm. Neurosurgery 64:1090–1099. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000346023.52541.0A. discussion 1099-1101

Pomeraniec IJ, Taylor DG, Cohen-Inbar O, Xu Z, Lee Vance M, Sheehan JP (2019) Radiation dose to neuroanatomical structures of pituitary adenomas and the effect of Gamma Knife radiosurgery on pituitary function. J Neurosurg 132:1499–1506. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.1.JNS182296

Puzzilli F, Ruggeri A, Mastronardi L, Agrillo A, Ferrante L (1999) Anterior clinoidal meningiomas: report of a series of 33 patients operated on through the pterional approach. Neuro Oncol 1:188–195. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/1.3.188

Rahi JS, Cumberland PM, Peckham CS (2009) Visual impairment and vision-related quality of life in working-age adults: findings in the 1958 British birth cohort. Ophthalmology 116:270–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.018

Risi P, Uske A, de Tribolet N (1994) Meningiomas involving the anterior clinoid process. Br J Neurosurg 8:295–305

Romani R, Laakso A, Kangasniemi M, Lehecka M, Hernesniemi J (2011) Lateral supraorbital approach applied to anterior clinoidal meningiomas: experience with 73 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery 68:1632–1647. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0b013e318214a840. discussion 1647

Russell SM, Benjamin V (2008) Medial sphenoid ridge meningiomas: classification, microsurgical anatomy, operative nuances, and long-term surgical outcome in 35 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery 62:1169–1181. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000333783.96810.58

Sade B, Lee JH (2008) High incidence of optic canal involvement in clinoidal meningiomas: rationale for aggressive skull base approach. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 150:1127–1132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-008-0143-y. discussion 1132

Salgado Lopez L, Munoz Hernandez F, Asencio Cortes C, Tresserras Ribo P, Alvarez Holzapfel MJ, Molet Teixido J (2018) Extradural anterior clinoidectomy in the management of parasellar meningiomas: Analysis of 13 years of experience and literature review. Neurocirugia (Astur) 29:225–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucir.2018.04.002

Slavin ML, Lam BL, Decker RE, Schatz NJ, Glaser JS, Reynolds MG (1993) Chiasmal compression from fat packing after transsphenoidal resection of intrasellar tumor in two patients. Am J Ophthalmol 115:368–371

Sughrue M, Kane A, Rutkowski MJ, Berger MS, McDermott MW (2015) Meningiomas of the Anterior Clinoid Process: Is It Wise to Drill Out the Optic Canal? Cureus 7:e321. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.321

Takano K, Hida K, Kuwabara Y, Yoshimitsu K (2017) Intracranial arterial wall enhancement using gadolinium-enhanced 3D black-blood T1-weighted imaging. Eur J Radiol 86:13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.10.032

Talacchi A, Hasanbelliu A, D'Amico A, Regge Gianas N, Locatelli F, Pasqualin A, Longhi M, Nicolato A (2018) Long-term follow-up after surgical removal of meningioma of the inner third of the sphenoidal wing: outcome determinants and different strategies. Neurosurg Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-018-1018-1

Taussky P, Kalra R, Coppens J, Mohebali J, Jensen R, Couldwell WT (2011) Endocrinological outcome after pituitary transposition (hypophysopexy) and adjuvant radiotherapy for tumors involving the cavernous sinus. J Neurosurg 115:55–62. https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.2.JNS10566

Tayebi Meybodi A, Lawton MT, Yousef S, Guo X, Gonzalez Sanchez JJ, Tabani H, Garcia S, Burkhardt JK, Benet A (2018) Anterior clinoidectomy using an extradural and intradural 2-step hybrid technique. J Neurosurg 130:238–247. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.8.JNS171522

Tobias S, Kim CH, Kosmorsky G, Lee JH (2003) Management of surgical clinoidal meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus 14:e5

Tomasello F, de Divitiis O, Angileri FF, Salpietro FM, Davella D (2003) Large sphenocavernous meningiomas: is there still a role for the intradural approach via the pterional-transsylvian route? Acta Neurochir (Wien) 145:273–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-003-0003-8. discussion 282

Verma SK, Sinha S, Sawarkar DP, Singh PK, Gupta D, Agarwal D, Satyarthee G, Kumar R, Singh M, Suri A, Chandra PS, Kale SS, Sharma BS (2016) Medial sphenoid wing meningiomas: EXPERIENCE with microsurgical resection over 5 years and a review of literature. Neurol India 64:465–475. https://doi.org/10.4103/0028-3886.181548

Vu HT, Keeffe JE, McCarty CA, Taylor HR (2005) Impact of unilateral and bilateral vision loss on quality of life. Br J Ophthalmol 89:360–363. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2004.047498

Xie Y, Yang Q, Xie G, Pang J, Fan Z, Li D (2016) Improved black-blood imaging using DANTE-SPACE for simultaneous carotid and intracranial vessel wall evaluation. Magn Reson Med 75:2286–2294. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.25785

Xie T, Zhang XB, Yun H, Hu F, Yu Y, Gu Y (2011) 3D-FIESTA MR images are useful in the evaluation of the endoscopic expanded endonasal approach for midline skull-base lesions. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 153:12–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-010-0852-x

Yao A, Pain M, Balchandani P, Shrivastava RK (2018) Can MRI predict meningioma consistency?: a correlation with tumor pathology and systematic review. Neurosurg Rev 41:745–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-016-0801-0

Yin Z, Hughes JD, Trzasko JD, Glaser KJ, Manduca A, Van Gompel J, Link MJ, Romano A, Ehman RL, Huston J 3rd (2017) Slip interface imaging based on MR-elastography preoperatively predicts meningioma-brain adhesion. J Magn Reson Imaging 46:1007–1016. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25623

Yonekawa Y, Ogata N, Imhof HG, Olivecrona M, Strommer K, Kwak TE, Roth P, Groscurth P (1997) Selective extradural anterior clinoidectomy for supra- and parasellar processes Technical note. J Neurosurg 87:636–642. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1997.87.4.0636

Zhang N, Guo L, Ge J, Qiu Y (2014) Endoscopic transsphenoidal treatment of a prolactinoma patient with brain and optic chiasmal herniations. J Craniofac Surg 25:e271-272. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000000632

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Lausanne.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the local Ethical Committee (Geneva Ethics Committee Board no. 11-233R, NAC 11-085R) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

For this retrospective type of study, formal consent is not required.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Comments

The authors have made numerous literature-based recommendations for treatment strategies for anterior clinoidal meningiomas, and this paper is useful for any neurosurgeons.

Anterior clinoid meningiomas show thickening of the anterior clinoid, often with optic canal invasion, thickening of the cavernous sinus wall, and cavernous sinus invasion. When removing the tumor, meticulous procedure is required to peel off it from the optic nerve, internal carotid artery, posterior communicating artery, anterior choroidal artery, and its perforating branch. In recent years, surgical treatment results related to the preservation and improvement of visual function have improved, but caution is required because there is still a risk of serious complications in the case of a huge lesion with major vessels encasement. For lesions showing cavernous sinus invasion, there are cases in which it is difficult to preserve visual function and local tumor control for long-term period even when combined with SRS or radiation therapy. Therefore, it is important to consider the treatment policy tailored based on various factors such as the patient’s age, tumor size and shape, growth rate, and neurological symptoms.

Hiroki Morisako, Takeo Goto, Kenji Ohata

Osaka, Japan

This review is based on a previous case series and meta-analysis by the same group of authors ((EANS skull base section) recently published in a different journal. The aim of this article is to share the EANS recommendations (level C) regarding the surgical management of clinoidal meningiomas with the global neurosurgical community.

This review is based on a previous case series and meta-analysis by the same group of authors ((EANS skull base section) recently published in a different journal. The aim of this article is to share the EANS recommendations (level C) regarding the surgical management of clinoidal meningiomas with the global neurosurgical community.

Therefore, the methodology is largely based on a previous work and an internal discussion among the group. As a reviewer, this is not the typical manuscript that will be subject to critique in terms of methodology or level of evidence etc. because as we all know, our level of evidence in skull base surgery is limited to level III (single institution experience or expert opinion based on a small case series. The value of studies such as the current is the effort to gather as much information from multiple institutions/experienced surgeons and present it in a more appealing recipe for practice. The recipe is usually in the form of directions or recommendations short of guidelines.

In this manuscript, this group of experts managed to achieve their goal to some extent given the challenge of lack of homogeneity of this subject in the literature.

As a skull base surgeon that deals with these tumors quite often, I do agree with the authors final recommendations of tailoring treatment to maximally preserve QOL, do no harm, perform a skull base approach that offers optimum exposure and surgical maneuverability, anterior clinoidectomy for optic nerve decompression and/or eradicating the origin of the tumor, do not chase the tumor into the cavernous sinus, and most of all, do not lose the internal carotid artery trying the peel the adherent last piece of tumor. In such cases, the patient will have a better QOL with STR and SRS upon progression of the residual tumor.

In terms of chiasmopexy, it’s better to leave it off.

A. Samy Youssef

Denver, USA

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Tumor—Meningioma

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Starnoni, D., Tuleasca, C., Giammattei, L. et al. Surgical management of anterior clinoidal meningiomas: consensus statement on behalf of the EANS skull base section. Acta Neurochir 163, 3387–3400 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-021-04964-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-021-04964-3