Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to reveal the risk factors including intraoperative brain stem auditory evoked potential (BAEP) changes and to define parameter and warning values of BAEP beyond which the probability of hearing impairment rises significantly.

Methods

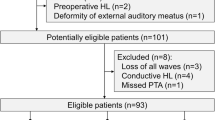

From April 1997 to February 2009, 1,156 patients underwent microvascular decompression (MVD) for hemifacial spasm (HFS) and their medical records and audiologic data. The intraoperative BAEP monitoring was performed in all operations during surgery from the time of administration of general anesthesia until the time of skin closure. Pure tone audiometry (PTA) and Speech Discrimination Score (SDS) were performed on all patients before and after surgery for categorizing the patterns of hearing loss. There were 825 females and 331 males with a mean age of 48.7 years (range 17–75 years). The mean symptom duration was 67.8 months (range 1–420 months).

Results

At the 1-year follow-up examination, 1,091 (94.4%) patients of the total 1,156 patients exhibited a cured state, and 65 (5.6%) patients had residual spasms. Hearing loss occurred in 46 patients (3.9%). In 26 patients, PTA was decreased more than 15 dB with a proportional decrease of the SDS. In 10 patients, poor SDS without hearing loss occurred. Total deafness was developed in 10 patients. A higher incidence of BAEP change and a poor recovery especially amplitude in wave V during surgery was observed in patients with poor SDS (eight patients) and total deafness (seven patients) (p = 0.000). Reduction of amplitude more than 50% in wave V was a strong indicator for a worse outcome of the hearing capacity. The difference in other risk factors according to hearing loss pattern was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Only female was significant (p = 0.005).

Conclusions

The intraoperative BAEP change and a poorer recovery, especially reduction of amplitude more than 50% in wave V, was a strong indicator for a worse outcome of the hearing capacity. Vigilant intraoperative monitoring of the BAEP and adequate steps for recovery of the BAEP change could prevent hearing loss after MVD for HFS.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (1995) Committee on hearing and equilibrium guidelines for the evaluation of results of treatment of conductive hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 113:186–187

Chung SS, Chang JW, Kim SH, Chang JH, Park YG, Kim DI (2000) Microvascular decompression of the facial nerve for the treatment of hemifacial spasm: preoperative magnetic resonance imaging related to clinical outcomes. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 142:901–906, discussion 907

Colosimo C, Bologna M, Lamberti S, Avanzino L, Marinelli L, Fabbrini G, Abbruzzese G, Defazio G, Berardelli A (2006) A comparative study of primary and secondary hemifacial spasm. Arch Neurol 63:441–444

Hyun SJ, Kong DS, Park K (2010) Microvascular decompression for treating hemifacial spasm: lessons learned from a prospective study of 1,174 operations. Neurosurg Rev 33:325–334, discussion 334

Jannetta PJ (1977) Observations on the etiology of trigeminal neuralgia, hemifacial spasm, acoustic nerve dysfunction and glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Definitive microsurgical treatment and results in 117 patients. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg) 20:145–154

Jannetta PJ, Resnick D (1996) Cranial rhizopathies. In: Youmans JR (ed) Neurological surgery: a comprehensive guide to the diagnosis and management of neurosurgical problems. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 3563–3574

McLaughlin MR, Jannetta PJ, Clyde BL, Subach BR, Comey CH, Resnick DK (1999) Microvascular decompression of cranial nerves: lessons learned after 4400 operations. J Neurosurg 90:1–8

Moller AR (1991) Interaction between the blink reflex and the abnormal muscle response in patients with hemifacial spasm: results of intraoperative recordings. J Neurol Sci 101:114–123

Ojemann RG, Levine RA, Montgomery WM, McGaffigan P (1984) Use of intraoperative auditory evoked potentials to preserve hearing in unilateral acoustic neuroma removal. J Neurosurg 61:938–948

Park K, Hong SH, Hong SD, Cho YS, Chung WH, Ryu NG (2009) Patterns of hearing loss after microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80:1165–1167

Polo G, Fischer C, Sindou MP, Marneffe V (2004) Brainstem auditory evoked potential monitoring during microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm: intraoperative brainstem auditory evoked potential changes and warning values to prevent hearing loss—prospective study in a consecutive series of 84 patients. Neurosurgery 54:97–104, discussion 104–106

Roeser RJ, Hosford-Dunn H, Valente M (2000) Audiology diagnosis. Thieme, New York, p 294

Samii M, Gunther T, Iaconetta G, Muehling M, Vorkapic P, Samii A (2002) Microvascular decompression to treat hemifacial spasm: long-term results for a consecutive series of 143 patients. Neurosurgery 50:712–718, discussion 718–719

Sindou M, Ciriano D, Fischer C (1991) Lessons from brain stem auditory evoked potential monitoring during microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm. In: Schramm J, Møller AR (eds) Intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring in neurosurgery. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 293–300

Sindou M, Fobe JL, Ciriano D, Fischer C (1990) Intraoperative brainstem auditory evoked potential in the microvascular decompression of the 5th and 7th cranial nerves. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 111:427–431

Conflicts of interest

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Comment

The present authors’ study, in spite of being retrospective, is of high importance for neurosurgeons dealing with MVD for Hemifacial spasm as it has been conducted on a large number of patients: 698. Their audiometric status was carefully assessed with pure tone audiometry (PTA) and Speech Discrimination Score (SDS) before and after surgery. Outcome was good, as 94.4% of the patients were cured; only 0.7% were deaf and 1% had poor SDS after surgery. Authors advocate to measure peak V amplitude for monitoring hearing function. They consider “reduction in amplitude of more than 50% a strong indicator for a worse outcome of hearing capacity.”

In our group, as well as in most other groups performing intraoperative BAEP recordings to monitor cochlear nerve function, it was admitted that the best warning of VIIIth nerve suffering, especially excessive stretching, was delay in latency. As a matter of fact, reduction in amplitude, when progressive, was estimated too sensitive to recording conditions or cooling of CPA during surgery. On the other hand, reduction in amplitude, especially when sudden, was considered a too late event for preventing vitality. However, when linked to significant reduction in amplitude of peak I, reduction in amplitude of peak V is a dramatic indicator of cochlea ischemia. For all these reasons, we do advise to study not only amplitude of both waves I and V but also peak V latency.

It has been recognized that an increase in latency of peak V, in the order of 1 ms, constitutes a critical warning signal that must be given by the neurophysiologist to the neurosurgeon to release retraction. Also, a reduction in amplitude of peak I (and consequently of peak V) means that surgery should be suspended to irrigate the arteries with warm saline and, if mechanically induced vasospasms are present, to topically apply a few droplets of 10% papaverine solution.

Marc Sindou

University of Lyon

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jo, KW., Kim, JW., Kong, DS. et al. The patterns and risk factors of hearing loss following microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. Acta Neurochir 153, 1023–1030 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-010-0935-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-010-0935-8