Abstract

Purpose

To examine the incidence of occult infection in revision spine surgeries and its correlation with preoperative inflammatory markers.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed all patients who underwent revision spine surgery and hardware removal between 2010 and 2016. Patients who had preoperative clinical signs of infection were excluded. The hardware and surrounding tissue culture results were obtained. The patients’ diagnosis and preoperative inflammatory marker (ESR, CRP, and procalcitonin) levels were recorded.

Results

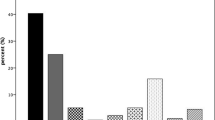

A total of 162 consecutive patients were included in this study. The patients’ mean age was 61 years (range 14–88). One hundred and three patients (63.6%) were female. Seventy-two patients (44.4%) had loose hardware and 88 patients (54.3%) had pseudarthrosis. Postoperatively, the hardware and/or surrounding tissue culture was positive in 15 patients (9.3%). The most commonly identified organisms were Propionibacterium acnes (7/15, 46.7%) and Staphylococcus (6/15, 40.0%). The other identified organisms were Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1/15, 6.7%) and Serratia marcescens (1/15, 6.7%). Only four patients with positive cultures had elevated preoperative ESR and CRP levels. Only two patients with positive cultures had elevated preoperative procalcitonin levels. There is no correlation between the patients’ preoperative ESR, CRP, procalcitonin levels, and positive culture results (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

Our study shows that occult infections are present in 9.3% of patients who underwent revision spine surgery and hardware removal although they did not have clinical signs of infection. Those commonly used preoperative inflammatory markers such as ESR, CRP, and procalcitonin may not be sensitive enough to detect occult infections in these patients.

Graphical abstract

These slides can be retrieved under Electronic Supplementary Material.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mok JM, Cloyd JM, Bradford DS, Hu SS, Deviren V, Smith JA, Tay B, Berven SH (2009) Reoperation after primary fusion for adult spinal deformity: rate, reason, and timing. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34:832–839. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0b013e31819f2080

Pichelmann MA, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, Good CR, O’Leary PT, Sides BA (2010) Revision rates following primary adult spinal deformity surgery: six hundred forty-three consecutive patients followed-up to twenty-two years postoperative. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 35:219–226. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0b013e3181c91180

Zhu F, Bao H, Liu Z, Bentley M, Zhu Z, Ding Y, Qiu Y (2014) Unanticipated revision surgery in adult spinal deformity: an experience with 815 cases at one institution. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 39:B36–B44. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000000463

Kelly MP, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, Agarwal R, Godzik J, Koester L (2013) Fate of the adult revision spinal deformity patient: a single institution experience. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 38:E1196–E1200. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0b013e31829e764b

Puvanesarajah V, Shen FH, Cancienne JM, Novicoff WM, Jain A, Shimer AL, Hassanzadeh H (2016) Risk factors for revision surgery following primary adult spinal deformity surgery in patients 65 years and older. J Neurosurg Spine 25:486–493. https://doi.org/10.3171/2016.2.SPINE151345

Chaichana KL, Bydon M, Santiago-Dieppa DR, Hwang L, McLoughlin G, Sciubba DM, Wolinsky JP, Bydon A, Gokaslan ZL, Witham T (2014) Risk of infection following posterior instrumented lumbar fusion for degenerative spine disease in 817 consecutive cases. J Neurosurg Spine 20:45–52. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.10.SPINE1364

Kasliwal MK, Tan LA, Traynelis VC (2013) Infection with spinal instrumentation: review of pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. Surg Neurol Int 4:S392–S403. https://doi.org/10.4103/2152-7806.120783

Shifflett GD, Bjerke-Kroll BT, Nwachukwu BU, Kueper J, Burket J, Sama AA, Girardi FP, Cammisa FP, Hughes AP (2016) Microbiologic profile of infections in presumed aseptic revision spine surgery. Eur Spine J 25:3902–3907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4539-8

Callanan TC, Lebl DR, Abjornson C, Cammisa JFP (2016) Can occult infection be demonstrated in the setting of pain in patients who have undergone spinal surgery? In: International Society for the Advancement of Spine Surgery (ISASS) Annual Conference

Bemer P, Corvec S, Tariel S, Asseray N, Boutoille D, Langlois C, Tequi B, Drugeon H, Passuti N, Touchais S (2008) Significance of Propionibacterium acnes-positive samples in spinal instrumentation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33:E971–E976. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0b013e31818e28dc

Uckay I, Dinh A, Vauthey L, Asseray N, Passuti N, Rottman M, Biziragusenyuka J, Riche A, Rohner P, Wendling D, Mammou S, Stern R, Hoffmeyer P, Bernard L (2010) Spondylodiscitis due to Propionibacterium acnes: report of twenty-nine cases and a review of the literature. Clin Microbiol Infect 16:353–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02801.x

Jakab E, Zbinden R, Gubler J, Ruef C, von Graevenitz A, Krause M (1996) Severe infections caused by Propionibacterium acnes: an underestimated pathogen in late postoperative infections. Yale J Biol Med 69:477–482

Chahoud J, Kanafani Z, Kanj SS (2014) Surgical site infections following spine surgery: eliminating the controversies in the diagnosis. Front Med (Lausanne) 1:7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2014.00007

Hadjipavlou AG, Mader JT, Necessary JT, Muffoletto AJ (2000) Hematogenous pyogenic spinal infections and their surgical management. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25:1668–1679

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no direct conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, X., Lieberman, I.H. Revision spine surgery in patients without clinical signs of infection: How often are there occult infections in removed hardware?. Eur Spine J 27, 2491–2495 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-018-5654-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-018-5654-5