Abstract

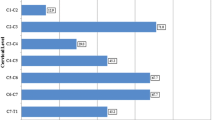

Klippel–Feil syndrome (KFS) is an uncommon condition noted primarily as congenital fusion of two or more cervical vertebrae. Superior odontoid migration (SOM) has been noted in various skeletal deformities and entails an upward/vertical migration of the odontoid process into the foramen magnum with depression of the cranium. Excessive SOM could potentially threaten neurologic integrity. Risk factors associated with the amount of SOM in the KFS patient are based on conjecture and have not been addressed in the literature. Therefore, this study evaluated the presence and extent of SOM and the various risk factors and clinical manifestations associated therein in patients with KFS. Twenty-seven KFS patients with no prior history of surgical intervention of the cervical spine were included for a prospective radiographic and retrospective clinical review. Radiographically, McGregor’s line was utilized to evaluate the degree of SOM. Anterior and posterior atlantodens intervals (AADI/PADI), number of fused segments (C1–T1), presence of occipitalization, classification-type, and lateral and coronal cervical alignments were also evaluated. Clinically, patient demographics and presence of cervical symptoms were assessed. Radiographic and clinical evaluations were conducted by two independent blinded observers. There were 8 males and 19 females with a mean age of 13.5 years at the time of radiographic and clinical assessment. An overall mean SOM of 5.0 mm (range = −1.0 to 19.0 mm) was noted. C2–C3 (74.1%) was the most commonly fused segment. A statistically significant difference was not found between the amount of SOM to age, sex-type, classification-type, AADI, PADI, and lateral cervical alignment (P > 0.05). A statistically significant greater amount of SOM was found as the number of fused segments increased (r = 0.589; P = 0.001) and if such levels included occipitalization (r = 0.616; P = 0.001). A statistically significant greater amount of SOM was also found with an increase in coronal cervical alignment (r = 0.413; P = 0.036). Linear regression modeling further supported these findings as the strongest predictive variables contributing to an increase in SOM. A 7.20 crude relative risk (RR) ratio [95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.05–49.18; risk differences (RD) = 0.52] was noted in contributing to a SOM greater than 4.5 mm if four or more segments were fused. Adjusting for coronal cervical alignment greater than 10°, five or more fused segments were found to significantly increase the RR of a SOM greater than 4.5 mm (RR = 4.54; 95% CI = 1.07–19.50; RD = 0.48). The RR of a SOM greater than 4.5 mm was more pronounced in females (RR = 1.68; 95% CI = 0.45–6.25; RD = 0.17) than in males. Eight patients (29.6%) were symptomatic, of which symptoms in two of these patients stemmed from a traumatic event. However, a statistically significant difference was not found between the presence of symptoms to the amount of SOM and other exploratory variables (P > 0.05). A mean SOM of 5.0 mm was found in our series of KFS patients. In such patients, increases in the number of congenitally fused segments and in the degree of coronal cervical alignment were strongly associated risk factors contributing to an increase in SOM. Patients with four or greater congenitally fused segments had an approximately sevenfold increase in the RR in developing SOM greater than 4.5 mm. A higher RR of SOM more than 4.5 mm may be associated with sex-type. However, 4.5 mm or greater SOM is not synonymous with symptoms in this series. Furthermore, the presence of symptoms was not statistically correlated with the amount of SOM. The treating physician should be cognizant of such potential risk factors, which could also help to indicate the need for further advanced imaging studies in such patients. This study suggests that as motion segments diminish and coronal cervical alignment is altered, the odontoid orientation is located more superiorly, which may increase the risk of neurologic sequelae.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Asamoto S, Nestler U, Shulz C, Boker DK (2003) A case of basilar impression complicated with left frontal meningioma. No Shinkei Geka 31:1003–1007

Baba H, Maezawa Y, Furusawa N, Chen Q, et al (1995) The cervical spine in the Klippel–Feil syndrome A report of 57 cases. Int Orthop 19:204–208

Baird PA, Robinson GC, Buckler WS (1967) Klippel–Feil syndrome. A study of mirror movement detected by electromyography. Am J Dis Child 113:546–551

Bonola A (1956) Surgical treatment of the Klippel–Feil syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Br 38-B:440–449

Casey AT, Crockard HA, Geddes JF, Stevens J (1997) Vertical translocation: the enigma of the disappearing atlantodens interval in patients with myelopathy and rheumatoid arthritis. Part I. Clinical, radiological, and neuropathological features. J Neurosurg 87:856–862

Chamberlain WE (1939) Basilar impression (platybasia). A bizarre developmental anamoly of the occipital bone and upper cervical spine with striking and misleading neurologic manifestations. Yale J Biol Med 11:487–496

Clark CR, Goetz DD, Menezes AH (1989) Arthrodesis of the cervical spine in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 71:381–392

Clarke RA, Catalan G, Diwan AD, Kearsley JH (1998) Heterogeneity in Klippel–Feil syndrome: a new classification. Pediatr Radiol 28:967–974

David KM, Copp AJ, Stevens JM, Hayward RD, Crockard HA (1996) Split cervical spinal cord with Klippel–Feil syndrome: seven cases. Brain 119(Pt6):1859–1872

David KM, Thorogood PV, Stevens JM, Crockard HA (1999) The dysmorphic cervical spine in Klippel–Feil syndrome: interpretations from developmental biology. Neurosurg Focus 6:E1

Davidson RC, Horn JR, Herndon JH, Grin OD (1977) Brain-stem compression in rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA 238:2633–2634

Delamarter RB, Bohlman HH (1994) Postmortem osseous and neuropathologic analysis of the rheumatoid cervical spine. Spine 19:2267–2274

Einig M, Higer HP, Meairs S, Faust-Tinnefeldt G, Kapp H (1990) Magnetic resonance imaging of the craniocervical junction in rheumatoid arthritis: value, limitations, indications. Skeletal Radiol 19:341–346

Farmer SF, Ingram DA, Stephens JA (1990) Mirror movements studied in a patient with Klippel–Feil syndrome. J Physiol 428:467–484

Feil A (1919) L’absence et la diminuation des vertebres cervicales (etude cliniqueet pathogenique); le syndrome dereduction numerique cervicales. Theses de Paris, France

Fischgold H, Metzger J (1952) Radio-tomography of the impression fractures of the cranial basis. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic 19:261–264

Glew D, Watt I, Dieppe PA, Goddard PR (1991) MRI of the cervical spine: rheumatoid arthritis compared with cervical spondylosis. Clin Radiol 44:71–76

Goel A, Phalke U, Cacciola F, Muzumdar D (2004) Surgical management of high cervical disc prolapse associated with basilar invagination—two case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 44:142–145

Gray SW, Romaine CB, Skandalakis JE (1964) Congenital fusion of the cervical vertebrae. Surg Gynecol Obstet 118:373–384

Guille JT, Miller A, Bowen JR, Forlin E, Caro PA (1995) The natural history of Klippel–Feil syndrome: clinical, roentgenographic, and magnetic resonance imaging findings at adulthood. J Pediatr Orthop 15:617–626

Gunderson CH (1968) Mirror movements in patients with the Klippel–Feil syndrome. Neuropathologic observations. Arch Neurol 18:675–679

Gunderson CH, Greenspan RH, Glaser GH, Lubs HA (1967) The Klippel–Feil syndrome: genetic and clinical reevaluation of cervical fusion. Medicine (Baltimore) 46:491–512

Helmi C, Pruzansky S (1980) Craniofacial and extracranial malformations in the Klippel–Feil syndrome. Cleft Palate J 17:65–88

Hensinger RN (1986) Orthopedic problems of the shoulder and neck. Pediatr Clin North Am 33:1495–1509

Hensinger RN, Lang JE, MacEwen GD (1974) Klippel–Feil syndrome. A constellation of associated anomalies. J Bone Joint Surg Am 56:1246–1253

Juberg RC, Gershanik JJ (1976) Cervical vertebral fusion (Klippel–Feil) syndrome with consanguineous parents. J Med Genet 13:246–249

Kawaida H, Sakou T, Morizono Y (1989) Vertical settling in rheumatoid arthritis. Diagnostic value of the Ranawat and Redlund-Johnell methods. Clin Orthop Relat Res 239:128–135

Klippel M, Feil A (1912) Un cas d’absence des vertebres cervicales. Avec cage thoracique remontant jusqu’a la base du crane (cage thoracique cervicale). Nouv Iconog Salpetriere 25:223–250

Locke R, Gardner I, van Epps EF (1966) Atlas-dens interval (ADI) in children: a survey based on 200 normal cervical spines. Am J Roentgenol 97:135

McAllion SJ, Paterson CR (1996) Causes of death in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Clin Pathol 49:627–630

McGregor M (1948) The significance of certain measurements of the skull in the diagnosis of basilar impression. Br J Radiol 21:171–181

McRae DL (1953) Bony abnormalities in the region of the foramen magnum: correlation of the anatomic and neurologic findings. Acta Radiol 40:335–354

McRae DL, Barnum AS (1953) Occipitalization of the atlas. Am J Roentgenol 70:23–45

Menezes AH, Ryken TC (1992) Craniovertebral abnormalities in Down’s syndrome. Pediatr Neurosurg 18:24–33

Menezes AH, VanGilder JC, Clark CR, el-Khoury G (1985) Odontoid upward migration in rheumatoid arthritis. An analysis of 45 patients with “cranial settling”. J Neurosurg 63:500–509

Nagib MG, Maxwell RE, Chou SN (1984) Identification and management of high-risk patients with Klippel–Feil syndrome. J Neurosurg 61:523–530

Nagib MG, Maxwell RE, Chou SN (1985) Klippel–Feil syndrome in children: clinical features and management. Childs Nerv Syst 1:255–263

Pizzutillo PD, Woods M, Nicholson L, MacEwen GD (1994) Risk factors in Klippel–Feil syndrome. Spine 19:2110–2116

Rana NA, Hancock DO, Taylor AR, Hill AG (1973) Upward translocation of the dens in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 55:471–477

Ranawat CS, O’Leary P, Pellicci P, Tsairis P et al (1979) Cervical spine fusion in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 61:1003–1010

Redlund-Johnell I, Pettersson H (1984) Radiographic measurements of the cranio-vertebral region. Designed for evaluation of abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 25:23–28

Riew KD, Hilibrand AS, Palumbo MA, Sethi N, Bohlman HH (2001) Diagnosing basilar invagination in the rheumatoid patient. The reliability of radiographic criteria. J Bone Joint Surg Am 83-A:194–200

Ritterbusch JF, McGinty LD, Spar J, Orrison WW (1991) Magnetic resonance imaging for stenosis and subluxation in Klippel–Feil syndrome. Spine 16:S539–S541

Rouvreau P, Glorion C, Langlais J, Noury H, Pouliquen JC (1998) Assessment and neurologic involvement of patients with cervical spine congenital synostosis as in Klippel–Feil syndrome: study of 19 cases. J Pediatr Orthop B7:179–185

Samartzis D, Herman J, Lubicky JP, Shen FH (2006) Classification of congenitally fused cervical patterns in Klippel–Feil patients: epidemiology and role in the development of cervical spine-related symptoms. Spine 31:E798–E804

Samartzis D, Lubicky JP, Herman J, Kalluri P, Shen FH (2006) Symptomatic cervical disc herniation in a pediatric Klippel–Feil patient: the risk of neural injury associated with extensive congenitally fused vertebrae and a hypermobile segment. Spine 31:E335–E338

Sawin PD, Menezes AH (1997) Basilar invagination in osteogenesis imperfecta and related osteochondrodysplasias: medical and surgical management. J Neurosurg 86:950–960

Shen FH, Samartzis D, Jenis LG, An HS (2004) Rheumatoid arthritis: evaluation and surgical management of the cervical spine. Spine J 4:689–700

Shen FH, Samartzis D, Herman J, Lubicky JP (2006) Radiographic assessment of segmental motion at the atlantoaxial junction in the Klippel–Feil patient. Spine 31:171–177

Slatis P, Santavirta S, Sandelin J, Konttinen YT (1989) Cranial subluxation of the odontoid process in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 71:189–195

Steinbok P (1995) Dysraphic lesions of the cervical spinal cord. Neurosurg Clin N Am 6:367–376

Taggard DA, Menezes AH, Ryken TC (2000) Treatment of Down syndrome-associated craniovertebral junction abnormalities. J Neurosurg 93:205–213

Thomsen MN, Schneider U, Weber M, Johannisson R, Niethard FU (1997) Scoliosis and congenital anomalies associated with Klippel–Feil syndrome types I–III. Spine 22:396–401

Tracy MR, Dormans JP, Kusumi K (2004) Klippel–Feil syndrome: clinical features and current understanding of etiology. Clin Orthop Relat Res 424:183–190

Wackenheim A, Capesius P (1975) Roentgen diagnosis of the cervical spine. Radiologe 15:311–316

Acknowledgment

In preparation of this manuscript, the authors have no competing or financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Samartzis, D., Kalluri, P., Herman, J. et al. Superior odontoid migration in the Klippel–Feil patient. Eur Spine J 16, 1489–1497 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-0280-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-0280-z