Abstract

The Japanese diagnostic criteria for autoimmune gastritis (AIG) were established by the “Study Group on the establishment of diagnostic criteria for type A gastritis,” which is related to a workshop associated with the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society (JGES) and the Committee of AIG Research Group (CARP). The criteria were set as follows: the cases of confirmed diagnosis are patients in whom either the endoscopic or histological findings, or both, meet the requirements for AIG and who are confirmed to be positive for gastric autoantibodies (either anti-parietal cell or anti-intrinsic factor antibodies, or both). The presentation of endoscopic findings of early-stage AIG in the diagnostic criteria was withheld owing to the need for further accumulation and characterization of endoscopic clinical data. Therefore, diagnosis of early-stage AIG only requires histological confirmation and gastric autoantibody positivity. Suspected cases are patients in whom either the endoscopic or histological findings, or both, meet only the requirements for AIG. Histological findings only meet the requirements for early stage. AIG has been underdiagnosed in the past, but our study group’s newly proposed diagnostic criteria will enable a more accurate and early diagnosis of AIG. The criteria can be used to stratify patients into various high-risk groups for gastric tumors and pernicious anemia. They would allow the establishment of an appropriate surveillance system in the coming years. Nevertheless, issues such as establishing the endoscopic findings of early-stage AIG and obtaining Japanese insurance coverage for gastric autoantibody tests require attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autoimmune gastritis (AIG, type A gastritis) is a unique type of gastritis in which parietal cells are destroyed by autoimmune mechanisms, resulting in the production of autoantibodies (anti-parietal cell antibodies: PCA) against proton pumps (H+/K+ ATPase). In 1973, Strickland and Mackay [1] reported two types of chronic atrophic gastritis—types A and B, with the former regarded as the end stage of AIG.

Until recently, AIG has been considered a rare disease in Japan; however, its frequency has steadily risen [2,3,4]. Possible factors contributing to the increase in AIG include the promotion of endoscopic screening; group D (negative for H. pylori and positive for pepsinogen [PG] [5]) findings in gastric cancer risk stratification tests; evaluation for macrocytic anemia [6], iron deficiency anemia, thyroid disease [7,8,9], and gastric cancer [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]; close examination of gastric neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]; and the presence of AIG in a subset of repeat cases of H. pylori eradication by 13C-urea breath test (UBT) [25]. Terao et al. [26] retrospectively reviewed the clinical and endoscopic characteristics of 245 AIG cases collected from 11 institutions in Japan and showed that the best diagnostic indicators for AIG were endoscopic findings (31.2%), followed by macrocytic anemia (16.1%), and repeated H. pylori eradication due to 13C-UBT false positivity (15.1%).

A characteristic endoscopic finding of AIG is corpus-dominant advanced atrophy [26,27,28,29,30,31]. In addition, sticky adherent dense mucus and remnant oxyntic mucosa may be observed in the corpus [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Moreover, magnified endoscopic findings [32,33,34], such as white globe appearance (WGA) [35, 36] and cast-off skin appearance (CSA) [36], have been reported, with few reports of early-stage AIG in which reverse atrophy has not fully developed [30, 37,38,39,40,41].

Several factors have clinical significance in the diagnosis of AIG. First, vitamin B12 deficiency increases the risk of pernicious anemia and neurological diseases such as subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord [42, 43], peripheral neuropathy, and dementia. Second, hyposecretion of gastric acid can lead to iron deficiency anemia. Third, a high risk of gastric cancer and gastric NETs increases the risk of developing AIG. Finally, autoimmune diseases such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis are often associated with other organs (polyglandular autoimmune syndrome IIIb) [44].

However, currently, no clear diagnostic criteria for AIG have been established. Thus, a comprehensive diagnosis is made from findings such as atrophic endoscopic findings in the gastric body to the fundus, presence of gastric autoantibodies, high serum gastrin levels, and characteristic histological findings (destruction/disappearance of parietal cells, pseudopyloric gland or intestinal metaplasia, enterochromaffin-like [ECL] cell hyperplasia, and gastrin cell hyperplasia).

In this article, we propose the diagnostic criteria for AIG in Japan, including its endoscopic and histologic characteristics.

Background to the creation of the Japanese diagnostic criteria for AIG

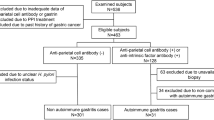

Numerous cases should be examined to create the diagnostic criteria for AIG. In 2015, the Committee of AIG Research Group (CARP) was established, which centered on approximately ten facilities in Japan that were actively conducting clinical research on AIG. An achievement of this meeting was that the results of a multicenter study involving a clinicopathological examination of 245 AIG cases were reported at the American College of Gastroenterology in 2017 (Digestive Disease Week) and published in Digestive Endoscopy in 2020 [27].

“Study Group on the establishment of diagnostic criteria for type A gastritis”, an affiliated study group of the JGES, was established in 2019. By May 2021, three study groups were held (published in 2020), and in May 2022, the diagnostic criteria were published as a report of results [31]. The endoscopic findings in these diagnostic criteria were established based on discussions at the CARP, the results of the multicenter study [27], and presentations at affiliated study groups. The histological findings were selected based on evidence such as international diagnostic criteria [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62] and presentations and papers by the affiliated study groups [63, 64].

Outline of the diagnostic criteria for AIG

In Western countries, AIG diagnosis is based on the characteristic histopathological findings, the presence of PCA, and/or anti-intrinsic factor antibody (IFA) tests [49,50,51,52,53,54], since the main purpose of endoscopy is to collect gastric mucosal tissues. However, this article discusses the diagnostic criteria for AIG, emphasizing endoscopic findings, histologic findings, and the presence of gastric autoantibodies. In Table 1, we showed the differences in diagnostic criteria for AIG between Japan and some other countries.

Table 2 shows the diagnostic criteria for AIG. The cases of confirmed diagnosis were set as those that satisfied both of the following conditions: severe mucosal atrophy predominantly from the gastric body to the fundus based on endoscopic and/or histological findings, and positivity for gastric autoantibodies using PCA and/or IFA tests. The suspected cases were set as those that satisfied only the condition of severe mucosal atrophy predominantly from the gastric body to the fundus (Table 2). Serum gastrin and pepsinogen levels are useful for diagnosing AIG [65], but were not adopted in the diagnostic criteria because they are not specific findings.

Histological findings of early-stage AIG were included in this proposed diagnostic criteria, although its endoscopic findings were not presented owing to the need to accumulate further endoscopic clinical data [30, 37, 41]. Therefore, diagnosis of early-stage AIG requires histological confirmation and gastric autoantibody positivity. The suspected cases of early-stage AIG are those with no atrophy on endoscopy, only histological findings of early stage are noted, and gastric autoantibodies are absent (Table 2).

Endoscopic findings of AIG

Advanced stage

AIG is characterized by corpus-dominant advanced atrophy, wherein uniform mucosal blood vessels are visible in the corpus [26,27,28,29,30,31]; this was used as the main diagnostic criterion (Fig. 1). A Japanese multicenter study [27] showed that the modified Kimura–Takemoto classification [66] O4 (O-P) was the most common gastric atrophy type (90.1%; 200/220), followed by O1–3 (5.9%; 13/221) among AIG patients. Most AIG cases do not show an atrophic border, although few cases show incomplete gastric body atrophy. For accurate diagnoses, it is essential to fully extend the greater curvature of the gastric body during endoscopy.

In addition to corpus-dominant advanced atrophy, the sticky adherent dense mucus (Fig. 2a) and remnant oxyntic mucosa (Fig. 2b) are characteristic findings from the gastric body to the fundus, and hyperplastic polyps are useful for diagnosing AIG [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Sticky adherent dense mucus refers to pale yellow-to-white mucus formed in the fundus and upper part of the corpus due to decreased gastric juice secretion associated with severe mucosal atrophy. This adherent mucus cannot easily be removed by washing it with water. A Japanese multicenter study [27] reported adherent mucus in 32.4% of AIG patients. In addition, it has been reported that overgrowth of urease-positive bacteria other than H. pylori due to the sticky mucus associated with achlorhydria in AIG led to false-positive 13C-UBT results and misdiagnosis in patients who were refractory to eradication therapy [25].

Remnant oxyntic mucosa (oxyntic mucosa pseudopolyps [67]) refers to fundic gland mucosa that is preserved in a localized area during diffuse atrophy of the gastric mucosa. In a Japanese multicenter study [27], remnant oxyntic mucosa was observed in 31.5% of AIG cases. Its shape was classified into five types: flat localized (48.6%), pseudopolyp-like (22.9%), island shaped (18.6%), extensive (7.1%), and granular (2.9%).

Foveolar-type hyperplastic polyps are more frequently observed than conventional atrophic gastritis. Maruyama et al. [26] analyzed endoscopic findings in 20 AIG and non-AIG cases each and observed a significantly higher incidence of foveolar-type hyperplastic polyps in AIG cases (AIG: 50%; non-AIG: 15%).

Although the antral area is generally considered to have no or mild atrophy and/or inflammation, there are cases in which the gastric mucosa is red or faded due to present or past H. pylori infection or bile reflux. Furthermore, patients with H. pylori infection also experience atrophy and/or inflammation; thus, the antral area is not necessarily a normal color. Additionally, patchy redness (Fig. 3a), red streaks (Fig. 3b), and circular wrinkle-like patterns (Fig. 3c) may also be helpful for AIG diagnosis [26,27,28,29,30,31].

Early stage

Recently, early-stage AIG without severe mucosal atrophy has been reported [30, 37,38,39,40,41]. Kotera et al. [37] reported two cases of early-stage AIG in a 48-year-old man and a 70-year-old woman. In these patients, atrophic changes without intestinal metaplasia were predominant in the lesser curvature of the corpus, and the characteristic endoscopic AIG finding was pseudopolyp-like reddish nodules on the non-atrophic mucosa of the greater curvature of the corpus. Ayaki et al. [38] reported two cases of early-stage AIG in two women (35 and 40 years old). According to the authors, severe corporal atrophy was not complete, and swelling of the gastric mucosa in the corpus and a mosaic pattern in the fundus were observed. In addition, Kishino et al. [39] reported diffusely erythematous and edematous fundic gland mucosa and subepithelial capillary network expansion. Furthermore, Maruyama et al. [30] reported the findings of early-stage AIG as mildly edematous fundic gland mucosa without an observed regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC) and diffuse spreading of enlarged gastric pits with a groove-like border. They reported that indigo-carmine spraying accentuated the mucosal pattern of the gastric pits, which were recognized as fine, salmon-roe-like nodular lesions.

Therefore, as Fig. 4 shows, early-stage AIG may be detected if reddened and mildly edematous gastric pits are diffusely observed in the corporal mucosa without RAC despite the absence of H. pylori infection. Particularly, suspecting AIG is crucial in complicated cases of thyroiditis. As described above, although common endoscopic findings of early-stage AIG are being documented, further accumulation and consideration of cases is desirable.

Endoscopic findings of early-stage AIG. Reddened and mildly edematous gastric pits are diffusely observed in the corporal mucosa without RAC despite the absence of H. pylori infection. The folds of the greater curvature of the corpus are preserved. a Greater curvature of the antral area. b Gastric body (observation looking upward). c Gastric body (observation looking downward)

Histological stage classification and histological features of AIG

Histological findings aid in classifying AIG into early stage, florid stage, and end stage, depending on the degree of progression of atrophy [48, 55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. Histological findings in our proposed diagnostic criteria are also divided into early stage, advanced florid stage, and advanced end stage, and their histological features are described (Table 3) [63, 64]. The definition of early-stage AIG concerning for histological findings differs greatly between Japan (Watanabe [63, 64]) and the West (Greenson [48]). Moreover, early-stage AIG in the West includes the advanced florid stage of AIG in the Japanese criteria.

To objectively recognize various cells, chromogranin A (synaptophysin is recommended if chromogranin A cannot be used) immunohistochemical staining can support the histological evaluation for ECL cells, H+/K+ ATPase staining for parietal cells, pepsinogen-I staining for chief cells, MUC6 staining for mucous neck cells, and gastrin staining for G cells. The recommended biopsy sites are the greater curvature of the pyloric antrum (2 cm proximal to the pyloric ring) and the greater curvature of the upper gastric body (however, when obtaining a biopsy specimen would impose a physical burden on the patient, such as in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy, using a single point in the greater curvature of the upper gastric body is acceptable). Furthermore, one biopsy of each of the gastric angles and middle lesser curvature of the gastric body is recommended to determine the presence or absence of atrophy in the gastric body and the presence or absence of H. pylori infection. Avoiding intestinal metaplasia as much as possible during a biopsy is important to accurately detect G and ECL cells [31, 63, 64].

-

(1) Early stage (Fig. 5, Table 3)

-

Chief cells often transform to pyloric gland cells/mucous neck cells (pseudopyloric gland cells); thus, the normal two-layered structure of fundic glands, i.e., the parietal cell/ mucous neck cell layer and the chief cell layer are obscured, although the parietal and mucous neck cell layer is preserved. Many parietal cells remain, although swelling, intraluminal protrusion, and shedding (these changes in parietal cells are key findings for early stage) are observed. Hyperplasia of ECL is either absent or mild, and mild-to-moderate lymphocytic/plasma cell infiltration is observed between the gastric glands. Gastrin (G) cells in the pyloric gland mucosa also show mild hyperplasia in the early stage.

-

Early-stage AIG is diagnosed when the above-mentioned histological findings are observed. Lymphocytic infiltration/plasma cell infiltration in the stroma between the oxyntic glands and hyperplasia of G cells in the pyloric glands is also used as a diagnostic aid.

-

-

(2) Advanced florid stage (Fig. 6, Table 3)

-

Gastric glands of the fundic mucosa are occupied by many-to-moderate numbers of mucous neck cell glands (pseudopyloric glands) and/or pyloric glands. Moreover, parietal cells are markedly decreased or absent if parietal cells are present, and marked degeneration would be noted. Additionally, elongation of the gastric pit and shortening of the fundic gland are observed, and hyperplasia of ECL cells is observed.

-

Marked decrease or disappearance of parietal cells is an important finding, and cases of this with ECL cell hyperplasia are diagnosed as advanced florid-stage AIG. G cell hyperplasia is also used as a diagnostic aid.

-

-

(3) Advanced end stage (Fig. 7, Table 3)

-

This is a progression of the advanced florid stage. End stage findings may be additionally seen in some cases. The gastric glands are dominated by moderate-to-severe intestinal metaplasia and contain a small amount of pyloric and mucous neck glands (pseudopyloric glands). Elongation of the gastric pit is more advanced, only a small number of gastric glands remain, and hyperplasia of ECL cells can be observed. The diagnosis is the same as that of the advanced florid stage.

-

Histological features of early stage (greater curvature of the corpus). a The fundic gland mucosal structure that is almost similar to normal is preserved, although there is the elongation of the gastric pit (ratio of the gastric pit length to the gastric gland length: 1.0:1.8), and there is moderate chronic inflammatory cell infiltration between the fundic glands (stronger in the glandular area than in the gastric pit area). Numerous residual parietal cells exhibit pseudohypertrophy (degenerative swelling and cell protrusion). (HE staining). b Intraglandular hyperplasia of the ECL cells is observed (chromogranin A staining)

Histological features of advanced florid stage (greater curvature of the corpus). a The normal fundic gland mucosa structure has disappeared, the lengths of the gastric pit and glandular are 0.39 and 0.29 mm, respectively, (ratio: 1.0:0.7), and there is the elongation of the gastric pit and shortening of the gastric gland. The dashed line indicates the boundary between the gastric pit and gastric gland (HE staining). b Intraglandular linear hyperplasia of the ECL cells is observed (chromogranin A staining)

Histological features of advanced end stage (greater curvature of the corpus). a The normal fundic gland mucosa structure has disappeared, intestinal metaplasia has become severe, and a small amount of the pyloric gland mucosa remains at the center of this photo. The gastric pit length/the gastric gland duct length ratio is 0.34/0.08 mm (ratio: 4.2:1.0). (HE staining). b Intraglandular ECL cell hyperplasia has become clear. (chromogranin A staining)

Gastric autoantibodies

An autoimmune mechanism causes AIG; thus, gastric autoantibodies (PCA and IFA) are important diagnostic items, and their sensitivity and specificity are reported to be 81% and 90%, respectively, for PCA and 27% and 100%, respectively, for IFA [68]. However, the assessment of IFA is particularly expensive and is not covered by health insurance in Japan; thus, PCA, whose measurement cost is relatively inexpensive, is commonly used in many facilities. PCA concentration gradually increases to a peak value and then decreases as gastric mucosa alteration progresses [69, 70].

Notably, PCA is evaluated using a fluorescent antibody test in which the patient’s serum is diluted tenfold; a > tenfold result is considered positive, although a tenfold result may be a false positive. Therefore, the diagnostic criteria were set as “at least tenfold is positive, but there is a possibility of changes in the future in consideration of false positives.” Currently, the lack of insurance coverage in Japan for both gastric autoantibody tests is an issue, and it is hoped that the publication of our proposed diagnostic criteria will be a tool for soliciting insurance coverage for these tests.

Conclusions

AIG diagnosis is significant for classifying patients into high-risk groups for gastric tumors, such as gastric cancer and NETs, and pernicious anemia, as well as for conducting regular surveillance. Our study group’s newly proposed diagnostic criteria in this article are expected to decrease the rate of underdiagnosis of AIG and promote the detection of early-stage AIG. Furthermore, the criteria can act as a framework for determining appropriate medical care. Urgent issues requiring resolution include establishing the endoscopic findings of early-stage AIG obtaining national health insurance coverage in Japan for gastric autoantibody tests.

References

Strickland RG, Mackay IR. A reappraisal of the nature and significance of chronic atrophic gastritis. Am J Dig Dis. 1973;18:426–40.

Notsu T, Adachi K, Mishiro T, et al. Prevalence of autoimmune gastritis in individuals undergoing medical checkups in Japan. Intern Med. 2019;58:1817–23.

Aoki R, Yasuda M, Shunto J, Haruma K. Type A gastritis detected during endoscopic examination. Stomach Intestine. 2019;54:1046–52 ((in Japanese)).

Nishizawa T, Yoshida S, Watanabe H, et al. Clue of diagnosis for autoimmune gastritis. Digestion. 2021;102:903–10.

Terao S, Tome M, Kure I, et al. Most cases categorized into the group D are not those with complete elimination of Helicobacter pylori infection because of advanced atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. Jpn J Helicobacter Res. 2013;14:5–14 ((in Japanese)).

Toh BH, van Driel IR, Gleeson PA. Pernicious anemia. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1441–8.

Alexandraki KI, Nikolaou A, Thomas D, et al. Are patients with autoimmune thyroid disease and autoimmune gastritis at risk of gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms type 1? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2014;80:685–90.

Whittingham S, Youngchaiyud U, Mackay IR, et al. Thyrogastric autoimmune disease. Studies on the cell-mediated immune system and histocompatibility antigens. Clin Exp Immunol. 1975;19:289–99.

Centanni M, Marignani M, Gargano L, et al. Atrophic body gastritis in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1726–30.

Elsborg L, Mosbech J. Pernicious anaemia as a risk factor in gastric cancer. Acta Med Scand. 1979;206:315–8.

Stockbrügger RW, Menon GG, Beilby JO, et al. Gastroscopic screening in 80 patients with pernicious anemia. Gut. 1983;24:1141–7.

Hsing AW, Hansson LE, McLaughlin JK, et al. Pernicious anemia and subsequent cancer. A population-based cohort study. Cancer. 1993;71:745–50.

Vannella L, Lahner E, Osborn J, et al. Systematic review: gastric cancer incidence in pernicious anaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:375–82.

Zhang H, Jin Z, Cui R, et al. Autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis in Chinese: a study of 320 patients at a large tertiary medical center. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:150–6.

Yoshida K, Yamatsuji T, Matsubara M, et al. Four cases of gastric cancer in patients with autoimmune gastritis. Kawasaki Med J. 2019;45:75–81.

Kitamura S, Muguruma N, Okamoto K, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of early gastric cancer associated with autoimmune gastritis. JGH Open. 2021;16:1210–5.

Lehtola J, Karttunen T, Krekelä I, et al. Gastric carcinoids with minimal or no macroscopic lesion in patients with pernicious anemia. Hepatogastroenterology. 1985;32:72–6.

Borch K, Renvall H, Kullman E, et al. Gastric carcinoid associated with the syndrome of hypergastrinemic atrophic gastritis. A prospective analysis of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:435–44.

Annibale B, Azzoni C, Corleto VD, et al. Atrophic body gastritis patients with enterochromaffin-like cell dysplasia are at increased risk for the development of type I gastric carcinoid. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1449–56.

Vannella L, Sbrozzi-Vanni A, Lahner E, et al. Development of type I gastric carcinoid in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1361–9.

Sjöblom SM, Sipponen P, Karonen SL, et al. Mucosal argyrophil endocrine cells in pernicious anaemia and upper gastrointestinal carcinoid tumours. J Clin Pathol. 1989;42:371–7.

Sato Y, Imamura H, Kaizaki Y, et al. Management and clinical outcomes of type I gastric carcinoid patients: retrospective, multicenter study in Japan. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:377–84.

Sato Y, Hashimoto S, Mizuno K, et al. Management of gastric and duodenal neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6817–28.

Magris R, De Re V, Maiero S, et al. Low pepsinogen I/II ratio and high gastrin-17 levels typify chronic atrophic autoimmune gastritis patients with gastric neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020;11: e00238.

Furuta T, Baba S, Yamade M, et al. High incidence of autoimmune gastritis in patients misdiagnosed with two or more failures of H. pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:370–7.

Maruyama Y, Yoshii S, Kageoka M, et al. Endoscopic findings of autoimmune gastritis-chronic atrophic gastritis type A. Stomach Intestine. 2019;54:998–1009 ((in Japanese)).

Terao S, Suzuki S, Yaita H, et al. Multicenter study of autoimmune gastritis in Japan: clinical and endoscopic characteristics. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:364–72.

Kamada T, Monobe Y, Haruma K. Clinical features and endoscopic findings of autoimmune gastritis and resultant gastric cancer. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2021;63:1520–37 ((in Japanese)).

Kamada T, Maruyama Y, Monobe Y, et al. Endoscopic features and clinical importance of autoimmune gastritis. Dig Endosc. 2022;34:700–13.

Maruyama Y, Yoshii S, Terai T. Endoscopic diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis. J Jpn Soc Gastroenterol. 2022;119:511–9 ((in Japanese)).

Kamada T, Watanabe H, Furuta T, et al. New proposal from the study group for the establishment of diagnostic criteria for type A gastritis of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society for diagnosing autoimmune gastritis. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2023; 65:173–82 (in Japanese).

Yagi K, Nakamura A, Sekine A, et al. Features of the atrophic corpus mucosa in three cases of autoimmune gastritis revealed by magnifying endoscopy. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012: 368160.

Anagnostopoulos K, Ragunath K, Shonde A, et al. Diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis by high resolution magnification endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4586–7.

Kato M, Uedo N, Toth E, et al. Differences in image-enhanced endoscopic findings between Helicobacter pylori-associated and autoimmune gastritis. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E22-30.

Ayaki M, Kobara H, Matsunaga T, et al. A case of type A gastritis with several white globe appearances. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2019;61:1226–30 ((in Japanese)).

Maruyama Y, Yoshii S, Kageoka M, et al. Features of magnifying endoscopic findings in type A gastritis. Stomach and Intestine. 2018;53:1516–21 ((in Japanese)).

Kotera T, Oe K, Kushima R, Haruma K. Multiple pseudopolyps presenting as reddish nodules are a characteristic endoscopic finding in patients with early-stage autoimmune gastritis. Intern Med. 2020;59:2995–3000.

Ayaki M, Aoki R, Mastunaga T, et al. Endoscopic and upper gastrointestinal barium X-ray radiography images of early-stage autoimmune gastritis: a report of two cases. Intern Med. 2021;60:1691–6.

Kishino M, Yao K, Hashimoto H, et al. A case of early autoimmune gastritis with characteristic endoscopic findings. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2021;14:718–24.

Kotera T, Yamanishi M, Kushima R, et al. Early autoimmune gastritis presenting with a normal endoscopic appearance. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2022;15:547–52.

Kishino M, Nonaka K. Endoscopic features of autoimmune gastritis: focus on typical images and early images. J Clin Med. 2022;11:3523.

Zhang N, Li RH, Ma L, et al. Subacute combined degeneration, pernicious anemia and gastric neuroendocrine tumor occurred simultaneously caused by autoimmune gastritis. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1.

Taniguchi M, Sudo G, Sekiguchi Y, et al. Autoimmune gastritis concomitant with gastric adenoma and subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14: e242836.

Betterle C, Zanchetta R. Update on autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes (APS). Acta Biomed. 2003;74:9–33.

Torbenson M, Abraham SC, Boitnott J, et al. Autoimmune gastritis: distinct histological and immunohistochemical findings before complete loss of oxyntic glands. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:102–9.

Rugge M, Fassan M, Pizzi M, et al. Autoimmune gastritis: histology phenotype and OLGA staging. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1460–6.

Pittman ME, Voltaggio L, Bhaijee F, et al. Autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis: recognizing precursor lesions for appropriate patient evaluation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1611–20.

Greenson JK, Lauweers GY, Montgomery EA, et al editors. Diagnostic pathology. In: Gastrointestinal. 3rd ed. Salt Lake City, UT, USA: Elsevier; 2019. p. 140–3.

Vargas JA, Alvarez-Mon M, Manzano L, et al. Functional defect of T cells in autoimmune gastritis. Gut. 1995;36:171–5.

Miceli E, Lenti MV, Padula D, et al. Common features of patients with autoimmune atrophic gastritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:812–4.

Minalyan A, Benhammou JN, Artashesyan A, et al. Autoimmune atrophic gastritis: current perspectives. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2017;10:19–27.

Carabotti M, Lahner E, Esposito G, et al. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms in autoimmune gastritis: a cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96: e5784.

Kalkan Ç, Soykan I. Differences between older and young patients with autoimmune gastritis. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:1090–5.

Massironi S, Cavalcoli F, Zilli A, et al. Relevance of vitamin D deficiency in patients with chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis: a prospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:172.

Stolte M, Baumann K, Bethke B, et al. Active autoimmune gastritis without total atrophy of the glands. Z Gastroenterol. 1992;30:729–35.

Solcia E, Rindi G, Fiocca R, et al. Distinct patterns of chronic gastritis associated with carcinoid and cancer and their role in tumorigenesis. Yale J Biol Med. 1992;65:793–804.

Eidt S, Oberhuber G, Schneider A, et al. The histopathological spectrum of type A gastritis. Pathol Res Pract. 1996;192:101–6.

Sepulveda AR, Patil M. Practical approach to the pathologic diagnosis of gastritis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1586–93.

Neumann WL, Coss E, Rugge M, et al. Autoimmune atrophic gastritis–pathogenesis, pathology and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:529–41.

Coati I, Fassan M, Farinati F, et al. Autoimmune gastritis: pathologist’s viewpoint. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12179–89.

Kulnigg-Dabsch S. Autoimmune gastritis. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2016;166:424–30.

Massironi S, Zilli A, Elvevi A, et al. The changing face of chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis: an updated comprehensive perspective. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18:215–22.

Watanabe H. Histological diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis (type A gastritis): achievements and issues. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2021;63:991 ((in Japanese)).

Watanabe H. Histological diagnosis and stages of autoimmune gastritis-a new proposal. J Jpn Soc Gastroenterol. 2022;119:528–39 ((in Japanese)).

Furuta T, Yamade M, Uotani T, et al. Serological diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis. J Jpn Soc Gastroenterol. 2019;116:A268 ((in Japanese)).

Nakajima S, Watanabe H, Shimbo T, et al. Incisura angularis belongs to fundic or transitional gland regions in Helicobacter pylori-naïve normal stomach: sub-analysis of the prospective multi-center study. Dig Endosc. 2021;33:125–32.

Krasinskas AM, Abraham SC, Metz DC, et al. Oxyntic mucosa pseudopolyps: a presentation of atrophic autoimmune gastritis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:236–41.

Lahner E, Norman GL, Severi C, et al. Reassessment of intrinsic factor and parietal cell autoantibodies in atrophic gastritis with respect to cobalamin deficiency. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2071–9.

Tozzoli R, Kodermaz G, Perosa AR, et al. Autoantibodies to parietal cells as predictors of atrophic body gastritis: a five-year prospective study in patients with autoimmune thyroid diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10:80–3.

Nishizawa T, Watanabe H, Yoshida S, et al. Decreased anti-parietal cell antibody titer in the advanced phase of autoimmune gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:143–8.

Acknowledgements

This review article is the second publication of a paper in the Japanese journal of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society and has been approved by the editorial board of the Society. We would like to thank the researchers (Dr. Rika Aoki, Dr. Kazuhiko Oho, Dr. Koichi Kurahara, Dr. Takushi Gotoda, Dr. Yuichi Sato, and Dr. Joji Shunto) of the “Study Group on Establishment of Diagnostic Criteria for Type A Gastritis,” a study group affiliated with the Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Endoscopy. This study was approved by the same research group. There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing—original draft: TK, HW, TF, ST, YM, HK, and RK. Writing—review and editing: TK HW, TF, ST, YM, and HK. Supervision: TC and KH. Approval of the final manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamada, T., Watanabe, H., Furuta, T. et al. Diagnostic criteria and endoscopic and histological findings of autoimmune gastritis in Japan. J Gastroenterol 58, 185–195 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-022-01954-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-022-01954-9