Abstract

Background

The aims of this study were to assess the trajectory of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) during the last year of life in patients with advanced non-small–cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and to explore when and to what degree deterioration of symptoms and physical functioning accelerate towards the end of life.

Methods

Data from two RCTs of first-line chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC was analyzed. HRQOL was assessed repeatedly using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and LC13. Changes in HRQOL scores were investigated relative to the time of death.

Results

The study sample included 730 patients, with a median of four HRQOL assessments per patient (range 1–9). Fatigue, dyspnea, appetite loss, and cough were the most pronounced symptoms in all phases of the disease trajectory. The deterioration rates of global quality of life, physical function, and key symptoms were relatively slow until 4 months before death. Then, the decline accelerated, and for physical function, fatigue, and dyspnea, there was a very rapid decline in the last 2 months.

Conclusions

Patients with advanced NSCLC experience a high symptom burden that worsens over time, especially in the last 4 months. Regular symptom monitoring may help identify where patients are in the disease trajectory, serve as a trigger for changes in anticancer and symptomatic treatment, and facilitate discussions about end-of-life care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for an estimated 10 million deaths in 2020 [1]. For the large number of patients dying of cancer, maintaining quality of life represents a major treatment goal throughout the disease trajectory. Several studies have shown that palliative care concurrent with anticancer treatment contributes to improved symptom management, better quality of life, and less psychological distress at the end of life [2,3,4,5]. Hence, international guidelines state that dedicated attention to supportive and palliative needs of patients with advanced cancer should be the standard of care [6, 7].

A key element in integrated models of oncological and palliative care is systematic assessment of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in terms of symptoms, functioning, and well-being, i.e., essential components of health-related quality of life (HRQOL). PROs are important to identify new or worsening symptoms and should be taken into consideration when choosing and evaluating treatment. Baseline scores and changes in HRQOL are prognostic factors for survival [8,9,10]. Still, little is known about which changes in HRQOL over time may be expected in patients with advanced cancer, especially towards the end of life.

For health care personnel, increased insight in the course of HRQOL may help assess prognosis, anticipate care needs and identify goals for timely interventions aiming to maintain or improve patients’ quality of life. For patients and their next of kin, information about the disease and its effects is requested in order to deal with their situation [11, 12]. And as the disease progresses, they need to know about which symptoms and functional problems to expect.

The typical “cancer illness trajectory” begins with a period of relatively preserved functional status, followed by a period of marked deterioration and increased symptoms at the end of life [13]. In line with this theory, previous studies in advanced cancer patients have found a marked worsening of functioning and various symptoms in the last months of life [14,15,16,17,18]. However, these studies have predominantly focused on the terminal phase [14, 16], included small and/or heterogeneous patient samples [15, 17, 18], or used assessment tools which evaluate symptoms, but not functioning or overall quality of life [17].

Most cases of lung cancer are diagnosed at an advanced stage, and for patients with metastases, the median survival in population-based studies is less than a year [19, 20]. It has been described that lung cancer patients have more symptoms than other cancer patients [21, 22]. Consequently, a comprehensive analysis of data derived from patients with advanced lung cancer is relevant when trying to understand the pattern and magnitude of changes in symptom burden and functional abilities during the last year of life. The objective of this study was to assess the HRQOL trajectory in the last year of life in patients with advanced non-small–cell lung cancer (NSCLC), using time to death as the point of reference. Furthermore, we examined when and to what degree deterioration of symptoms and physical functioning accelerate towards the end of life.

Methods

Patients

We pooled data from two randomized clinical trials (RCTs) comparing first-line chemotherapy regimens in advanced NSCLC. RCT 1 (n = 436) compared pemetrexed plus carboplatin (PC) with gemcitabine plus carboplatin (GC) for up to four cycles [23]. RCT 2 (n = 437) compared vinorelbine plus gemcitabine (VG) with vinorelbine plus carboplatin (VC) for up to three cycles [24]. Both RCTs were conducted by the same research network, and the eligibility criteria were identical. At inclusion, all patients were chemotherapy naïve and had NSCLC stage IV or IIIB not eligible for curative treatment and WHO performance status (PS) of 0–2. Both trials were approved by ethic committees, and all patients gave written informed consent. In addition to the study treatment, 32% and 43% of patients in RCT 1 and 2, respectively, later received systemic second-line therapy, and 41% and 49% received palliative radiotherapy. Symptomatic treatment and palliative care were provided by local cancer centers according to their local routines.

HRQOL was assessed on the European Organization for Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ) Core (C30) and the lung-cancer specific module LC13 at inclusion, after every 3-week cycle of chemotherapy and then every 8 weeks up to week 52 or 57 in RCT 1 and RCT 2, respectively. In both RCTs, survival and HRQOL outcomes between the treatment arms were similar. All patients who were registered as deceased in the RCT database and had completed at least one HRQOL assessment within 365 days prior to death were included in the present study.

HRQOL measures

The EORTC QLQ-C30 consists of a global quality of life scale, five multi-item function scales, three multi-item symptom scales, and six single-item symptom scales [25]. The LC13 has one multi-item symptom scale evaluating dyspnea and nine single-item scales measuring symptoms commonly associated with lung cancer and its treatment [26]. Scores of both questionnaires were linearly transformed to a scale ranging from 0 to 100 [27]. A high score in global quality of life and on the functioning scales indicates a good health status, while a high symptom scale score represents more symptoms.

Data analysis

All questionnaires completed during the last year of life were included in the analyses. The assessments were aligned relative to the time of death. For example, month 1 included assessments 1–30 days before death. The mean HRQOL scores within four intervals were then calculated: Less than 3 months before death, 3 to 6 months before death, 6 to 9 months before death, and 9 to 12 months before death. If patients had completed multiple questionnaires within an interval, the average score for that patient was used. The difference in mean HRQOL scores between 9 and 12 months before death and the last 3 months was compared with a mixed linear model with time period as a categorical predictor. The compliance rate was calculated by dividing the number of QLQs completed each month before death with the number of QLQs expected according to the assessment schedules in the RCTs.

We defined a difference in mean scores of 10 points or more as clinically relevant and a difference of more than 20 points as a large difference [28, 29]. The QLQ-C30 scores were compared with age- and gender-adjusted reference values from the general Norwegian population [30, 31]. Since HRQOL was assessed only up to a year after inclusion in the RCTs, sensitivity analyses were performed comparing trajectories for patients with a survival time of less than 12 months and those who lived 12 months or longer.

The change over time in global quality of life, physical function, and the key symptoms fatigue, pain, appetite loss, and dyspnea (LC13) were investigated with mixed linear models, with time before death as the explanatory variable. To test if we could identify time points for accelerated decline, we fitted piecewise models, allowing the change to vary at each month before death. A backward elimination procedure retaining only the significant parameters for the change rate was used to select a more interpretable final model. The level of statistical significance was defined as p less than 0.05. All analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 (College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics and HRQOL compliance

Of the 873 patients included in the two RCTs, 767 were deceased at database lock of whom 730 (95%) had completed at least one QLQ in the year before death and was eligible for the present analyses. Median age was 65 years, and 428 (59%) were men (Table 1). Median survival from inclusion in the RCTs was 5.8 months (range 0–25 months). The 730 patients completed a total of 3 183 QLQs, with a median of 4 per patient (range 1–9). The compliance rate decreased gradually from 96% 12 months before death to 80% 3 months before death. In the last 2 months, 75% and 39% of expected QLQs were completed.

HRQOL trajectories in relation to time to death

The mean global quality of life score was 58 (SD, 20) 9–12 months before death and decreased gradually to 50 (SD, 21) 3–6 months before death (Table 2). In the last 3 months, the mean score was 38 (SD, 21). The mean change from the last 9–12 months until the last 3 months was 20 points (p < 0.01). Other scales with a large worsening from the last 9–12 months to the last 3 months were physical, social, and role function (24, 21, and 25 points, respectively) and pain (20 points). Scales with a clinically relevant worsening of 10–19 points were fatigue, appetite loss, dyspnea, constipation, pain in arm/shoulder, or other parts of the body and cognitive function. The mean score trajectories for the 125 patients living longer than 12 months were similar to those for the patients living less than 12 months (data not shown).

Compared to the reference population, the mean scores for global quality of life, physical, social, role and emotional function, fatigue, dyspnea, appetite loss, and constipation were significantly worse (> 10 points) in all time intervals, including 9–12 months before death. For pain and nausea/vomiting, the difference to the reference population became clinically relevant from 6 months before death, and for insomnia and cognitive function in the last 3 months.

Rates of change in HRQOL towards the end of life

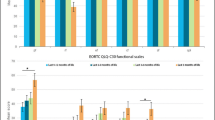

For global quality of life, the mean deterioration rate was 1.2 points/month 12 months before death, with a significant change to 6.2 points/month 4 months before death (Fig. 1). In the last month, the deterioration rate nearly tripled to 15.8 points/month. For physical function and pain, appetite loss, fatigue, and dyspnea, the deterioration was relatively slow (range 1–2 points/month) until 4 months before death (Fig. 2). Later, the decline accelerated, and for physical function, fatigue, and dyspnea (LC13), there was a very rapid decline the last 2 months (range 10–14 points/month).

The course of global quality of life during the last year of life. The circles reflect individual data points; the connected line the average scores in each month and the dashed line the estimated values from the piecewise linear mixed model. The deterioration rate increased significantly 4 and 1 month before death

Discussion

In this study, patients with advanced NSCLC experienced a substantial deterioration of HRQOL in the last year of life. Fatigue, dyspnea, appetite loss, and cough were the most pronounced symptoms and significantly worse than in the reference population in all phases of the disease trajectory. Notably, mean pain scores were not significantly worse than in the reference population until 6 months before death, but increased thereafter. The ability to carry out physical and social activities was markedly impaired even 9–12 months before death, and then decreased progressively. In contrast, cognitive and emotional functioning was relatively stable during the disease trajectory and only in the last months of life significantly worse than the reference population.

The finding that HRQOL worsens markedly in the last months of life is in line with clinical experience and other studies of cancer trajectories, conducted in more heterogenous patient populations [15,16,17]. However, comparison of symptomatology across studies is difficult due to differences in the patient samples and assessment strategies employed. In a Swedish study, patients with primary inoperable lung cancer were asked to rank their most distressing symptoms [32]. In all time periods before death, dyspnea, pain, and fatigue were consistently ranked as the most distressing symptoms. Like in our data, these symptoms were also reported as the most prevalent and the mean intensity increased significantly in the last 2 months before death [32].

In clinical practice, symptom deterioration between scheduled hospital visits may go unnoticed. Additionally, clinicians often miss or underestimate symptoms during consultations [33,34,35], which may further delay timely management. In the present study, the deterioration of key symptoms, physical function and global quality of life was relatively slow until 4 months before death. Then, increased decline was observed, especially in the last 2 months. Possibly, regular PRO monitoring (e.g., weekly or bi-weekly) could identify patients before the worsening has accelerated and the patient’s condition deteriorated. Since salvage therapies are mainly effective in patients with good performance status [36], earlier detection of relapse or disease progression may allow more patients to receive optimal treatment. Indeed, this may be an important mechanism of action in studies of PRO monitoring demonstrating not only improved HRQOL outcomes, but also increased survival [37,38,39,40]. Identifying patients with increasing symptoms being ineligible for more anticancer treatment is also important, since these may benefit from dedicated palliative care, including palliative radiotherapy to treat symptoms like pain and dyspnea [41, 42].

The EORTC measures have traditionally been used in research, but can also be used in routine cancer care [43]. Indeed, a recent review found that the QLQ-C30 was the most widely used measure in studies of PRO implementation in clinical practice [44]. A shortened version of the QLQ-C30, the C15-PAL, has been developed for cancer patients with a short life expectancy [45]. In the C15-PAL, the financial difficulties and diarrhea items are excluded, and the nausea/vomiting scale shortened to nausea only. In the current study, these three scales had low average scores during the trajectory, including the last 3 months. In the clinical practice setting, the PRO measures should focus on symptoms that are common, reflect changes in disease status, or are clearly linked with an intervention that could improve them. The results in the present study suggest that for patients with advanced NSCLC, the PAL-15 could be used instead of the QLQ-C30 in clinical practice. These questionnaires, and other PRO instruments, are now available in electronic formats, meaning the patients can complete assessments at home on web-based devices with the results immediately transferred to the medical record [46, 47].

A limitation of the current study is that both RCTs were conducted before the identification of predictive mutations for targeted therapies and the introduction of immunotherapy. However, despite the impressive results reported for these therapies, most patients develop progressive disease, and survival estimates in real-world populations are generally lower than those reported in pivotal clinical trials [19, 20]. Sensitivity analyses indicated that patients whose survival exceeded 12 months had the same HRQOL trajectories in the last period of life as patients with shorter survival. Another limitation is that data on post-study treatment was not recorded in sufficient detail to allow for analyses on how anticancer treatment affected the HRQOL trajectory. Furthermore, inclusion criteria in the RCTs were limited to relatively well-functioning patients (WHO PS 0–2), and the intensity of symptoms and functional problems found in this study may thus represent an underestimation of symptoms experienced in the overall population of patients with advanced NSCLC. Selection of patients with good performance status may also have delayed worsening of symptoms and functioning of patients.

In conclusion, this study shows that patients with advanced NSCLC experience a high symptom burden and significantly impaired quality of life in the last year of life. The degree of worsening increases substantially in the last 2 to 4 months. Regular symptom monitoring may help identify where patients are in the disease trajectory, indicate a need for changes in anticancer and symptomatic treatment, and facilitate discussions about end-of-life care.

References

Sung H et al (2021) Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71(3):209–249

Ferrell B et al (2015) Interdisciplinary palliative care for patients with lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 50(6):758–767

Temel JS et al (2017) Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 35(8):834–841

Temel JS et al (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363(8):733–742

Zimmermann C et al (2014) Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 383(9930):1721–1730

Ferrell BR et al (2017) Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: ASCO clinical practice guideline update summary. J Oncol Pract 13(2):119–121

Jordan K et al (2018) European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) position paper on supportive and palliative care. Ann Oncol 29(1):36–43

Ediebah DE et al (2014) Does change in health-related quality of life score predict survival? Analysis of EORTC 08975 lung cancer trial. Br J Cancer 110(10):2427–2433

Efficace F et al (2006) Is a patient’s self-reported health-related quality of life a prognostic factor for survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients? A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of EORTC study 08975. Ann Oncol 17(11):1698–1704

Gupta D, Braun DP, Staren ED (2012) Association between changes in quality of life scores and survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 21(5):614–622

Maguire R et al (2013) A systematic review of supportive care needs of people living with lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 17(4):449–464

Sklenarova H et al (2015) When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer 121(9):1513–1519

Murray SA et al (2005) Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 330(7498):1007–1011

Elmqvist MA et al (2009) Health-related quality of life during the last three months of life in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 17(2):191–198

Giesinger JM et al (2011) Quality of life trajectory in patients with advanced cancer during the last year of life. J Palliat Med 14(8):904–912

Hwang SS et al (2003) Longitudinal quality of life in advanced cancer patients: pilot study results from a VA medical cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage 25(3):225–235

Seow H et al (2011) Trajectory of performance status and symptom scores for patients with cancer during the last six months of life. J Clin Oncol 29(9):1151–1158

Raijmakers NJH et al (2018) Health-related quality of life among cancer patients in their last year of life: results from the PROFILES registry. Support Care Cancer 26(10):3397–3404

Brustugun OT et al (2018) Substantial nation-wide improvement in lung cancer relative survival in Norway from 2000 to 2016. Lung Cancer 122:138–145

Waterhouse D et al (2021) Real-world outcomes of immunotherapy-based regimens in first-line advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 156:41–49

Degner LF, Sloan JA (1995) Symptom distress in newly diagnosed ambulatory cancer patients and as a predictor of survival in lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 10(6):423–431

Johnsen AT et al (2009) Symptoms and problems in a nationally representative sample of advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med 23(6):491–501

Gronberg BH et al (2009) Phase III study by the Norwegian lung cancer study group: pemetrexed plus carboplatin compared with gemcitabine plus carboplatin as first-line chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 27(19):3217–3224

Flotten O et al (2012) Vinorelbine and gemcitabine vs vinorelbine and carboplatin as first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC. A phase III randomised controlled trial by the Norwegian Lung Cancer Study Group. Br J Cancer 107(3):442–7

Aaronson NK et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85(5):365–376

Bergman B et al (1994) The EORTC QLQ-LC13: a modular supplement to the EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) for use in lung cancer clinical trials. Eur J Cancer 30a(5):635–42

Fayers, P.M., N. Aaronson, and K. Bjordal, EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual (ed 3). 2001: Brussels, Belgium, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

Maringwa JT et al (2011) Minimal important differences for interpreting health-related quality of life scores from the EORTC QLQ-C30 in lung cancer patients participating in randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer 19(11):1753–1760

Osoba D et al (1998) Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16(1):139–144

Hjermstad MJ et al (1998) Using reference data on quality of life–the importance of adjusting for age and gender, exemplified by the EORTC QLQ-C30 (+3). Eur J Cancer 34(9):1381–1389

Hjermstad MJ et al (1998) Health-related quality of life in the general Norwegian population assessed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire: the QLQ=C30 (+ 3). J Clin Oncol 16(3):1188–1196

Tishelman C et al (2007) Symptom prevalence, intensity, and distress in patients with inoperable lung cancer in relation to time of death. J Clin Oncol 25(34):5381–5389

Laugsand EA et al (2010) Health care providers underestimate symptom intensities of cancer patients: a multicenter European study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 8:104

Basch E et al (2009) Adverse symptom event reporting by patients vs clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst 101(23):1624–1632

Fromme EK et al (2004) How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. J Clin Oncol 22(17):3485–3490

Hanna N et al (2017) Systemic therapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 35(30):3484–3515

Basch E et al (2017) Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 318(2):197–198

Basch E et al (2016) Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 34(6):557–565

Denis F et al (2019) Two-year survival comparing web-based symptom monitoring vs routine surveillance following treatment for lung cancer. JAMA 321(3):306–307

Denis, F., et al (2017) Randomized trial comparing a web-mediated follow-up with routine surveillance in lung cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 109(9).

Stevens, R., et al 2015 Palliative radiotherapy regimens for patients with thoracic symptoms from non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1: p. Cd002143.

Lutz S et al (2017) Palliative radiation therapy for bone metastases: update of an ASTRO evidence-based guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol 7(1):4–12

Wintner LM et al (2016) The use of EORTC measures in daily clinical practice-a synopsis of a newly developed manual. Eur J Cancer 68:73–81

Anatchkova M et al (2018) Exploring the implementation of patient-reported outcome measures in cancer care: need for more real-world evidence results in the peer reviewed literature. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2(1):64

Groenvold M et al (2006) The development of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: a shortened questionnaire for cancer patients in palliative care. Eur J Cancer 42(1):55–64

De Regge, M., et al 2019 Development and evaluation of an integrated digital patient platform during oncology treatment. Journal of Patient Experience p. 2374373518825142.

Krogstad H et al (2017) Development of EirV3: a computer-based tool for patient-reported outcome measures in cancer. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 1:1–14

Funding

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Are Kristensen, Bjørn Henning Grønberg, Øystein Fløtten, Stein Kaasa, and Tora Skeidsvoll Solheim. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Are Kristensen, and all the authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The present study was based on data from to randomized clinical trials, which both were approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway. The research was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration and principles of Good Clinical Practice.

Consent to participate

All the patients gave written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kristensen, A., Grønberg, B.H., Fløtten, Ø. et al. Trajectory of health-related quality of life during the last year of life in patients with advanced non-small–cell lung cancer. Support Care Cancer 30, 9351–9358 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07359-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07359-x