Abstract

Purpose

To synthesise findings from published studies on barriers and facilitators to Black men accessing and utilising post-treatment psychosocial support after prostate cancer (CaP) treatment.

Methods

Searches of Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Central, CINAHL plus and Scopus were undertaken from inception to May 2021. English language studies involving Black men aged ≥18 and reporting experiences of, or suggestions for, psychosocial support after CaP treatment were included. Low or moderate quality studies were excluded. Searches identified 4,453 articles and following deduplication, 2,325 were screened for eligibility. Two independent reviewers carried out screening, quality appraisal and data extraction. Data were analysed using thematic synthesis.

Results

Ten qualitative studies involving 139 Black men were included. Data analysis identified four analytical constructs: experience of psychosocial support for dealing with treatment side effects (including impact on self-esteem and fear of recurrence); barriers to use of psychosocial support (such as perceptions of masculinity and stigma around sexual dysfunction); facilitators to use of psychosocial support (including the influence of others and self-motivation); and practical solutions for designing and delivering post-treatment psychosocial support (the need for trusted healthcare and cultural channels).

Conclusions

Few intervention studies have focused on behaviours among Black CaP survivors, with existing research predominantly involving Caucasian men. There is a need for a collaborative approach to CaP care that recognises not only medical expertise but also the autonomy of Black men as experts of their illness experience, and the influence of cultural and social networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With advancements in prostate cancer (CaP) diagnosis and treatment procedures, survival rates for the disease have continued to improve [1]. However, survivors still experience reduced quality of life due to long-term treatment side effects which adversely impact on their physical and psychosocial well-being [2]. CaP treatment side effects may have different implications for Black men due to their disproportionately higher risk (1 in 4) of developing the disease earlier in life, in more aggressive forms and at more advanced stages than Caucasian men (1 in 8) [3].

Despite this poor prognosis, Black men are reportedly less likely to utilise external post-treatment support programmes (e.g., CaP support groups) [4], receive appropriate long-term follow-up care [5] or engage in existing psychosocial interventions as these have predominantly involved Caucasian men [2]. Evidence from research on Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups highlight correlations between ethnicity and health in which cancer survivors from ethnic minority groups reportedly record a lower uptake of cancer services compared with their majority Caucasian counterparts [6]. Factors which contribute to this disparity are currently not fully understood. However, there are suggestions that preference for alternative coping mechanisms (e.g., religion and spirituality) [7] and perceived lack of cultural sensitivity in patient-healthcare provider communications [8] may be contributory factors.

Previous reviews involving Black men and CaP have mostly focused on screening for early diagnosis [9], knowledge and perceptions [10], post-treatment experiences [11] or quality of life after diagnosis [12] and showed that there are ethnic disparities in how Black men perceive, experience and respond to a CaP illness. Understanding the barriers and facilitators to Black men’s utilisation of psychosocial support after CaP treatment will help to inform the design of useful and acceptable interventions effectively tailored to their support needs and preferences within their sociocultural context. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to synthesise findings from existing published studies on the barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilising post-treatment psychosocial support by Black men after CaP treatment (see operational definition of terms in Table 1).

The Candidacy model [14] which has been widely applied to understand uptake of healthcare services at a broad level [15, 16] is perceived as a useful theoretical framework to enhance conceptual understanding of findings from this review. Postulated by Dixon-woods et al. [14], the Candidacy model articulates how intersections between structural, cultural, organisational and professional factors influence people’s access and utilisation of healthcare services, especially among vulnerable and disadvantaged groups. The authors [17] defined candidacy as “a dynamic and contingent process,” which is iteratively shaped by individual-professionals interactions and the contextual conditions in which those interactions occur (for example, availability of resources). The seven domains of the Candidacy model include identification, navigation, the permeability of service, appearance at health services, adjudications, offers and resistance, and operating conditions [17].

Methods

Study design and search strategy

This systematic review is reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [18]. The review was conducted using a protocol (PROSPERO registration ID: CRD42020171488) [19] developed following recommended guidelines [20, 21]. Between January and February 2020, systematic searches were conducted on seven databases: Medline, Embase and PsychInfo via OVID, Cochrane database of Systematic Reviews and Central, CINAHL plus and Scopus, from inception to February 2020. The searches were conducted by an experienced information specialist (SG) and librarian (AW), using a validated peer review strategy [22] and search terms iteratively developed from the review aim and PICO (Population, Issue, Context and Outcome) framework for non-intervention studies [23]. Broadly, search terms were words related to: prostate cancer AND psychosocial support AND Black men (20). The search was adapted for each database, with the use of database-specific Thesaurus terms added where appropriate. Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were used to limit or broaden search results. A supplementary search strategy included searches on OpenGrey, Web of Science proceedings, Google Scholar, Prostate Cancer UK and Movember websites; consultation with professional colleagues; hand-searching of reference list of included articles; and author contact. Search results were managed using bibliographic software: Endnote and Covidence. Database searches were re-run in May 2021.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Primary studies were included if they: (i) involved Black men aged 18 years and above who had undergone active treatment for CaP and (ii) reported on their experiences or suggestions for psychosocial support (as defined above) at the post-treatment phase of their CaP journey. Studies were excluded if they were (i) grey literature which lacked clear methodology (for example, editorials), (ii) conference abstracts whose full papers could not be accessed, (iii) systematic reviews (as focus is on primary studies) or (iv) focused on different ethnic groups and/or cancer types and did not separate the views of Black men after CaP treatment.

Identification and selection of studies

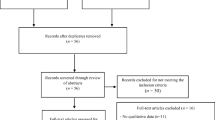

The searches yielded 4453 articles from which 2128 duplicates were removed (Fig. 1). Deduplication was systematically done (by SG) on Endnote and Covidence [24]. Titles and abstracts of the remaining 2325 studies were independently screened for relevance on Covidence [25] and 2169 papers were excluded. Full texts of the remaining 156 studies were screened for eligibility. Fifteen eligible studies were included for quality appraisal. Two reviewers (OB and OA or SG or MO) independently screened the studies and resolved conflicts through discussion.

Quality appraisal and data extraction

The CASP tool [26] was used to appraise qualitative (n = 10) and RCT (n = 1) studies whilst the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [27] was used for the mixed methods (n = 4) papers. Quality score was calculated by dividing “yes” tally by the total number of domains multiplied by 100%. For example, a qualitative study which scored “yes” in nine out of the ten domains on the qualitative CASP tool was scored 90%. Studies were rated as strong (≥ 70%) (n = 11), moderate (> 40% < 70%) (n = 0) or low (< 40%) (n = 4). The mixed methods studies (n = 4) were of low quality (17%) and were excluded. Likewise, the only RCT retrieved lacked sufficient data to address the review aim, and was also excluded. Therefore, ten qualitative studies were included in the review, and all were of high quality (≥ 70%) (Table 2). Two reviewers (OB and OA, MO, SG or EDM) independently appraised quality and extracted data using Microsoft Excel (Table 3). Conflicts were resolved by discussion.

Data analysis

We analysed data using thematic synthesis [28] which involved three stages. Firstly, we freely coded findings from each individual study using words directly from the reported data (where possible). We then aggregated similar codes into descriptive themes using labels which allowed us to stay close to the original data as much as possible. Lastly, we generated new analytical constructs by exploring similarities, differences and patterns in the descriptive themes and interpreting these in relation to the review aim. The new analytical themes were then labelled accordingly. Two reviewers (OB and AW) independently analysed data and deliberated developed themes with another two reviewers (OA and EDM). Data analysis was managed with NViVo 12 software.

Results

Overview

The ten qualitative studies [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] were published between 2004 and 2020 and conducted in the UK [32, 34, 36,37,38], USA [29, 31, 33, 35] and Canada [30]. A total of 139 Black men (60 AA, 60 BC, 18 BA and 1 unspecified) aged between 49 and 85 years were included in the studies (Table 3). Whilst the studies were all qualitative, data collection and analytic methods varied as shaped by their respective study designs (Table 3). Data analysis yielded four analytical constructs (Fig. 2): “experience of psychosocial support for dealing with treatment side effects,” “barriers to use of structured post-treatment psychosocial support,” “facilitators to use of structured post-treatment psychosocial support” and “practical solutions for designing and delivering structured post-treatment psychosocial support.”

Experience of psychosocial support for dealing with treatment side effects

A predominant theme across all but two [29, 31] of the studies was the psychological impact of treatment side effects (e.g., sexual dysfunction) on the men. Men expressed feelings of stress [32, 33, 35]; discouragement [30, 32, 36]; isolation from social contacts [32]; injured self-esteem (due to a restricted ability to perform their daily routines) [32, 35]; marital insecurities [35]; fear of cancer reoccurrence or fatality [33, 37]; and diminished masculinity [30, 33, 36] after treatment (Table 4 (1i)). Although desiring more information from their healthcare providers to manage these challenges, men recounted positive experiences of receiving unstructured practical and emotional support from their partner, family and wider social networks, including peers who had undergone a similar illness experience. These social networks supported the men through prayers, information provision, moral support and encouragement. In all ten studies, partners were unanimously highlighted as the main source of support for the men, through emotional and practical help, and enabling lifestyle changes where necessary (Table 4 (1ii–iv)).

Men also accessed structured support from local church communities [29, 31, 32, 36, 38] (n = 6), prostate cancer support groups [30, 32, 35, 37, 38] (n = 5), cultural community groups [32, 38] (n = 2) and an online support group [33] (n = 1). Support from local church communities was offered through communal prayers, and spiritual encouragement, which men reported as valuable (Table 4 (1v)). Men who attended a prostate cancer support group described it as a “safe place where they could find information, comfort, exchange thoughts and be open about their concerns and worries” [37]. Two studies [32, 38] reported men also accessed support through participation in health talks at cultural community groups where they had opportunity to discuss with other survivors who were ahead of them in the CaP journey (Table 4 (1vi)). Only one US-based study [33] reported men accessing information through a virtual support group on the internet.

Barriers to use of structured post-treatment psychosocial support

These are reported under four descriptive themes.

Self as a barrier — underpinned by masculinity concerns and personality types

Men reported exercising personal autonomy to decide their uptake of structured psychosocial support. Personality types (e.g., being a private person or being too shy) [33, 35, 37] and masculinity concerns [30, 32, 33, 35, 36] around losing their independence, self-esteem and to “avoid being perceived as weak” substantially influenced men’s reluctance to access structured psychosocial support. Using personal coping strategies such as resilience [32, 34, 36] and self-reliance [33, 34, 36, 38], and lacking conviction in intervention benefit [34], were additional barriers to men’s engagement with structured psychosocial support (Table 4 (2ai)).

Cultural stigmatisation of masculine sexual dysfunction

In some studies [35, 36, 38], men were reluctant to access structured psychosexual support in order to avoid perceptions of diminished masculinity often associated with post-treatment sexual dysfunction within their cultural setting. Men avoided public disclosure and highlighted that their CaP was not a subject for discussion at a social level due to concern that they would be perceived as effeminate within their cultural circle (Table 4 (3ai–iii)).

Healthcare system, structure and process as barriers

Findings showed that men perceived their routine CaP care is predominantly focused on clinical management of physical side effects of treatment, with minimal or no provision for structured psychosocial support. Some studies [32, 33, 36, 37] (n = 4) reported men were neither informed nor sign-posted to appropriate psychosocial support by healthcare professionals (HCPs) which meant they were not aware of existing services (Table 4 (2bi)). In one study [32] where men were sign-posted to support services, they reported that complicated referral procedures made it difficult for them to access such services (Table 4 (2bii)). Men highlighted a lack of psychosexual services (e.g., counselling) to help them deal with the psychological impact of sexual dysfunction (Table 4 (2biii–iv)). A few studies [32, 37] highlighted racial stereotyping of Black men’s sexuality by doctors (stereotypical comments from doctors on Black men prioritising their sex life over dealing with the CaP illness), which prevented men from openly expressing their need for psychosexual support during clinical consultations.

Financial and physical health challenge

Findings from a few studies [31, 34, 37] showed that financial challenges somewhat limited men’s uptake of structured psychosocial support. For example, some men [34] reported loss of income due to their CaP diagnosis. Thus, they prioritised returning to work over participation in a lifestyle intervention designed to help men deal with CaP treatment side effects. Men in a US-based study [31] highlighted lack of health insurance as a barrier to healthcare access among AA men (Table 4 (4i)). Physical limitations from old age, injuries from sports and other health challenges (e.g., from urinary incontinence) were additional barriers to men’s participation in physical activity intervention for CaP survivors [34] (Table 4 (4ii–iii)).

Facilitators to use of structured post-treatment psychosocial support

Facilitators were reported under two descriptive themes.

Influence of others

This finding emerged from all of the studies although from different perspectives. A few studies reported that men received support from their HCPs via information provision [36, 38] or sign-posting to hospital prostate support groups and social support agencies [32]. However, the psychosocial support men received from their HCPs appeared to be blurred along the different stages of the CaP spectrum as there was a lack of clarity on which support was received at the post-treatment phase of the illness journey (Table 4 (3ai)). Men who attended prostate support groups recalled receiving information and motivation to attend from their peers who were members of the group and had a similar CaP experience [30, 35, 37, 38] (Table 4 (3aii–iv)). In one of the studies [34], men narrated their partner influenced them to adhere to a lifestyle intervention which involved dietary changes for healthier living.

Self-motivation as informed by the illness experience and treatment side effects

Some studies [30, 33, 34, 38] reported men were self-motived to use developed psychosocial interventions because they perceived them as complementary to their existing dietary lifestyle or an indication of recovery from the CaP. Men reiterated a personal decision to regain their pre-diagnosis body shape and fitness naturally without dependence on medications, thus, they engaged with developed lifestyle interventions (Table 4 (3bi)). Some men viewed their CaP diagnosis as a stimulant to make necessary lifestyle changes they had always wanted to make, particularly as they grew older (for example, making dietary changes and engaging in CaP advocacy activities) (Table 4 (3bii)). Men acknowledged a significant impact of treatment-related sexual dysfunction on their sex lives and psychosocial well-being [33, 36] and had expectations for professional psychosexual support to be delivered as part of routine post-treatment CaP care (Table 4 (3biii)).

Practical solutions for designing and delivering structured post-treatment psychosocial support

Review findings identified some practical solutions for designing and delivering psychosocial support for Black men after CaP treatment. We also considered individual study authors’ recommendations (where linked to their participants’ narratives) as they offered additional useful insights which complemented the men’s suggestions. These are reported under five descriptive themes.

Delivering support through healthcare professionals as a trusted source

Perceiving HCPs as a skilled and trusted source of credible information, findings indicated Black men may be willing to engage with developed psychosocial interventions if they are either delivered or sign-posted by their HCPs [30, 32, 34, 36] (Table 4 (4ai–ii)). For psychosocial support delivered by HCPs, men suggested partners should be included and HCPs should prescribe their role in initiating sexual activity. Men explained this could help facilitate mutual problem-solving for sexual problems among couples, and reduce the psychological burden of sexual dysfunction on the men (Table 4 (4aiii)).

Using culturally trusted and acceptable channels

Review findings [29, 31,32,33, 38] showed that delivering psychosocial support through culturally acceptable and trusted avenues could potentially improve Black men’s use of such support as this will help to situate their illness experiences within their familiar setting and improve culturally sensitive cancer care for them. Some studies suggested the use of relatable local community champions or peers with shared ethnicity whom men can identify with, to provide peer support and information (Table 4 (4bi)). Reflecting on spirituality and faith beliefs as their key coping strategies, some men suggested the incorporation of faith-based interventions (e.g., counselling services and health education) in psychosocial support for CaP survivors within the Black community (Table 4 (4bii)).

Designing intervention content to appeal to Black men

Review findings showed that the content of developed interventions needs to be appealing to Black men, in order to stimulate their interest and engagement. Men highlighted the need for psychosocial support to achieve visible clinical impact (e.g., reduced PSA levels and regaining of pre-cancer body weight) and be targeted at allaying their fears of cancer reoccurrence (Table 4 (4ei)). Men also seemed to prefer psychosocial support which promotes independence, factual information, practical resources and couple-focused activities to enhance communication and mutual problem-solving. For group-based support programmes, it was suggested this should take into account disparities in men’s demographics so that men can identify with their counterparts from a similar age group (Table 4 (4eii)). Findings [29, 30, 32, 37] highlighted the need for improved cultural competence and sensitivity among HCPs when delivering psychosocial support to Black men with CaP by demonstrating a contextual understanding of the dynamics of masculinity within the Black cultural group and how these mediate their help-seeking for sexual problems after CaP treatment.

Prioritising self-help, flexibility and autonomy

Findings highlighted the need to consider Black men’s priority to retain their idealistic masculine identity when developing post-treatment psychosocial support for them. For example, there were suggestions that support programmes which prioritise men’s independence and personal autonomy [34] and are delivered to promote “self-management of sexual problems without appearing emotionally weak” [36] may be more appealing to Black men with CaP. In particular, men narrated the need for support programmes to be flexible and allow them to choose which aspects of the programme they would like to engage with, in their own time and at their own pace (Table 4 (4ci)).

Collaborative working between clinical and social networks

Study authors [29, 31, 32, 34] recommended the establishment of strategic links, referral procedures and information exchange between clinicians, social care agencies, religious and community organisations in developing and delivering affordable structured psychosocial support and CaP education programmes for Black men. The perception is that such collaboration could help to increase awareness and take-up of available support services by Black men if such information is disseminated at the grassroot level (Table 4 (4di)). All supporting quotes are presented in Table 4.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesised findings from existing published studies on the barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilising post-treatment psychosocial support by Black men after treatment for CaP. Some findings from this review resonate with evidence from studies on Caucasian men where practical issues [39], privacy concerns and lack of awareness of services [40] were likewise reported as barriers to men’s attendance at CaP support programmes. However, the current review has identified additional factors which are relevant to Black CaP survivors and which challenge assumptions that this population do not access external psychosocial support services predominantly because of an ingrained aversion towards public disclosure of their illness [4, 5]. Rather, there are wider factors which intersect between cultural, structural/organisational, personal and social factors, which influence Black men’s access and utilisation of organised psychosocial support programmes. This supports postulations from the Candidacy model [17] that the intersection of such factors impacts on people’s access and utilisation of healthcare services, especially among vulnerable and disadvantaged groups.

The theme around “self” as a barrier and facilitator to accessing and utilising psychosocial support in this review reinforces the centrality of personal autonomy and independence to how Black men with CaP perceive, navigate and respond to support services along their post-treatment journey [41, 42]. The “identification” and “appearance at health services” constructs of the Candidacy model postulate that an individual’s recognition of their need to seek help for symptoms they are experiencing, and their ability to articulate what help they require, substantially influence their uptake of healthcare services. Moreover, the masculine ideology of being in charge of key decisions as portrayed by men in the studies included in this review hints at the importance of viewing them as partners in developing psychosocial support through mutual decision-making and coproduction [43].

Using a conceptual model of coproduced healthcare, Batalden et al. [44] postulate that participatory interactions between patients and HCPs within their societal healthcare system are influenced by “the structure and function of the healthcare system” and wider social services. Men’s expectation in this review, of HCPs providing or sign-posting them to post-treatment psychosocial support, highlights the centrality of their role to the men’s illness journey. The Candidacy model [17] recognises HCPs as adjudicators of healthcare access with an important role to provide patient-centred support services (Adjudication), make patients aware of (Navigation) and facilitate their attendance (e.g., through referrals) at such services (Permeability of service). Prioritising self-help, flexibility and provision of factual information could further make the “operating conditions” of developed interventions appealing to Black men [17, 45]. Whilst there is an increasing use of online support among Caucasian men with CaP [46], review findings suggest this may be less appealing to Black men as only one study [33] reported men accessed online support groups. Fogel et al. [47] identified digital inequality, cultural preferences, trust issues and preference for face-to-face support as key barriers to engagement of African-Americans (AAs) in online cancer support groups.

Implications for practice

Whilst men mostly demonstrated personal autonomy in decision-making for their support preference, the influence of social networks (e.g., partners, peers and religious communities) on their help-seeking behaviour towards psychosocial support cannot be ignored. This suggests the potential benefit of a collaborative approach to CaP care which recognises the autonomy of men as experts of their illness experience, medical expertise of HCPs and influence of social networks on men’s help-seeking for post-treatment support. The use of culturally acceptable channels (e.g., partners and religious leaders) to mediate health behaviour change in Black men with CaP is well recognised in the literature [4, 48, 49] and should be adopted when developing post-treatment psychosocial support services for them. Given the increasing digitalisation of healthcare service delivery (including cancer services) [50] facilitated by rapid technological advancements and the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important for HCPs to consider the reluctance of Black men towards online support. Hence, they should highlight to men, the benefit of online support to promote flexibility and autonomy in health service delivery. Online support resources should also be intuitive, simple and interactive whilst prioritising patient’s data protection and safety online. Wider evidence on BAME groups [51, 52] suggest they may be receptive towards online interventions if accessible on mobile devices, and complemented with professional support.

Study limitations and directions for further research

This is the first systematic review to the best of our knowledge, which synthesised data from individual qualitative studies to produce a more in-depth conceptual and contextual evidence on barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilising structured psychosocial support by Black men after CaP treatment. However, this review has some limitations. Studies included were conducted in three different countries (UK, USA, and Canada) with disparities in healthcare structures and systems. Therefore, men’s respective contexts should be considered when interpreting review findings. For example, financial challenge was reported as a barrier in both US and UK studies but with differing perspectives. It was reported as a health insurance problem for US-based men, but expressed as inability to return to work quickly in the UK. This highlights the complexity of delineating diversities in the support priorities of CaP survivors despite having shared racial backgrounds. Most of the included studies did not provide details on length of time since the men were treated for CaP, which makes it difficult to understand how their support needs may have evolved through the post-treatment phase of their illness trajectory. Further research is needed to investigate this phenomenon. Search results showed a dearth of psychosocial intervention studies focused on behavioural issues among Black CaP survivors as these have predominantly involved Caucasian men [2, 53]. This important gap in the literature warrants further research.

Conclusions

This study is an incremental addition to the extant literature as it explores additional domains that were relatively unknown about psychosocial support utilisation among Black men after CaP treatment. This study is novel in that it: (1) showed that intersections between cultural, structural/organisational, personal and social factors influence access and utilisation of structured post-treatment psychosocial support services by Black CaP survivors; (2) highlighted the relevance of the Candidacy model for use in CaP research (beyond its use in healthcare services); and (3) highlighted unique factors (both barriers and facilitators) relevant to Black CaP survivors regarding their access to and uptake of psychosocial support post-treatment. Additional research should explore broader domains that might be relevant among more ethnically and geographically diverse Black CaP survivors as regards accessing and utilising structured psychosocial support post-treatment.

Availability of data and material

The data used in this systematic review are publicly available and included in the manuscript (see data extraction table and reference list).

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Cancer Research UK (2016) Prostate cancer: survival. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/prostate-cancer/survival. Accessed 16 Dec 2020

McCaughan E, McKenna S, McSorley O, Parahoo K (2015) The experience and perceptions of men with prostate cancer and their partners of the CONNECT psychosocial intervention: a qualitative exploration. J Adv Nurs 71(8):1871–1882

Prostate Cancer UK (2016) A Black man’s risk. Prostate Cancer UK, London Available at: https://prostatecanceruk.org/get-involved/black-men-and-prostate-cancer/prostate-cancer-and-your-risk [Accessed 16 December 2020].

Bamidele O (2019) Post-treatment for prostate cancer: the experiences and psychosocial needs of Black African and Black Caribbean men and their partners. Ulster University, Doctoral thesis

Khan S, Hicks V, Rancillo D, Langston M, Richardson K, Drake B (2018) Predictors of follow-up visits post radical prostatectomy. Am J Mens Health 12(4):760–765

Licqurish S, Phillipson L, Chiang P, Walker J, Walter F, Emery J (2017) Cancer beliefs in ethnic minority populations: a review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Eur J Cancer Care 26:1

Koffman J, Morgan M, Edmonds P, Speck P, Higginson IJ (2008) “I know he controls cancer”: the meanings of religion among Black Caribbean and White British patients with advanced cancer. Soc Sci Med 67(5):780–789

Bamidele O, McGarvey H, Lagan BM, Ali N, Chinegwundoh F, Parahoo K, McCaughan E (2017) Life after prostate cancer: a systematic literature review and thematic synthesis of the post-treatment experiences of Black African and Black Caribbean men. Eur J Cancer Care. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12784

Alexis O, Worsley A (2018) An integrative review exploring black men of African and Caribbean backgrounds, their fears of prostate cancer and their attitudes towards screening. Health Educ Res 33(2):155–166

Pedersen VH, Armes J, Ream E (2012) Perceptions of prostate cancer in Black African and Black Caribbean men: a systematic review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology 21(5):457–468

Rivas C, Matheson L, Nayoan J, Glaser A, Gavin A, Wright P, Wagland R, Watson E (2016) Ethnicity and the prostate cancer experience: a qualitative metasynthesis. Psycho-Oncology 25(10):1147–1156

Dickey SL, Ogunsanya ME (2018) Quality of life among black prostate cancer survivors: an integrative review. Am J Mens Health 12(5):1648–1664. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988318780857

American Cancer Society (2019) Understanding psychosocial support services Available at: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/emotional-side-effects/understanding-psychosocial-support-services.html [Accessed 16 December 2020]

Dixon-Woods M, Kirk D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur T, Harvey J, Hsu R, Katbamna S, Olsen R, Riley R (2005) Vulnerable groups and access to health care: a critical interpretive review. In: Report for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO). NCCSDO, London

Koehn S (2009) Negotiating candidacy: ethnic minority seniors’ access to care. Ageing Soc 29(4):585–608. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X08007952

Macdonald S, Blane D, Browne S, Conway E, Macleod U, May C, Mair F (2016) Illness identity as an important component of candidacy: contrasting experiences of help-seeking and access to care in cancer and heart disease. Soc Sci Med 168:101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.022

Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, Hsu R, Katbamna S, Olsen R, Smith L (2006) Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol 6(1):35

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Bamidele O., Alexis O., Ogunsanya M., Greenley S., Worsley A. & Mitchell E (2020). A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to access and utilisation of post-treatment psychosocial support by black men treated for prostate cancer. Protocol. PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020171488 Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020171488 [Accessed 8th December 2020]

Lefebvre C, Glanville J, Briscoe S, Littlewood A, Marshall C, Metzendorf M-I, Noel-Storr A, Rader T, Shokraneh F, Thomas J & Wieland LS. (2019) Chapter 4: searching for and selecting studies. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, 2019. Available at: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook . [Accessed 1 October 2019]

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2009). Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare. Available at: http://www.york.ac.uk/crd/SysRev/!SSL!/WebHelp/SysRev3.htm [Accessed 9 October 2019].

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C (2016) PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol 75:40–46

Munn Z, Stern C, Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Jordan Z (2018) What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med Res Methodol 18(5):1–9

Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T (2016) De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc 104(3):240–243

Covidence (2019) World-class systematic review management. Available at: https://www.covidence.org/home [Accessed 16 December 2020]

CASP Checklists (2020) Available at: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ [Accessed 7th September 2020]

Hong Q, Pluye P, Fabregues S, Bartletta G, Boardmanc F, Cargod M, Dagenaise P, Gagnonf M, Griffiths F, Nicolau B, O’Cathain A, Rousseau M, Vedela (2019) Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: a modified e-Delphi study. J Clin Epidemiol 111:49–59

Thomas J, Harden A (2008) Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 8(1):1

Hamilton J, Sandelowski M (2004) Types of social support in African Americans with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 31(4). https://doi.org/10.1188/04.ONF.792-800

Gray RE, Fergus KD, Fitch MI (2005) Two Black men with prostate cancer: a narrative approach. Br J Health Psychol 10(1):71–84

Jones RA, Wenzel J, Hinton I, Cary M, Jones NR, Krumm S, Ford JG (2011) Exploring cancer support needs for older African-American men with prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 19(9):1411–1419

Nanton V, Dale J (2011) It don’t make sense to worry too much: the experience of prostate cancer in African-Caribbean men in the UK. Eur J Cancer Care 20(1):62–71

Rivers BM, August EM, Quinn GP, Gwede CK, Pow-Sang JM, Green BL, Jacobsen PB (2012) Understanding the psychosocial issues of African American couples surviving prostate cancer. J Cancer Educ 27(3):546–558

Er V, Lane JA, Martin RM, Persad R, Chinegwundoh F, Njoku V, Sutton E (2017) Barriers and facilitators to healthy lifestyle and acceptability of a dietary and physical activity intervention among African Caribbean prostate cancer survivors in the UK: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 7(10):e017217. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017217

Imm KR, Williams F, Housten AJ, Colditz GA, Drake BF, Gilbert KL, Yang L (2017) African American prostate cancer survivorship: exploring the role of social support in quality of life after radical prostatectomy. J Psychosoc Oncol 35(4):409–423

Bamidele O, McGarvey H, Lagan BM, Parahoo K, Chinegwundoh MBE, F. & McCaughan, E. (2019) ‘Man in the driving seat’: a grounded theory study of the psychosocial experiences of Black African and Black Caribbean men treated for prostate cancer and their partners. Psycho-oncology 2019:1–9

Margiriti C, Gannon K, Thompson R, Walsh., & Green. J. (2019) Experiences of UK African-Caribbean prostate cancer survivors of discharge to primary care. Ethn Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2019.1606162

Wagland R, Nayoan J, Matheson L et al (2020) Adjustment strategies amongst black African and black Caribbean men following treatment for prostate cancer: findings from the Life After Prostate Cancer Diagnosis (LAPCD) study. Eur J Cancer Care 29:e13183. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13183

Hedden L, Pollock P, Stirling B, Goldenberg L, Higano C (2019) Patterns and predictors of registration and participation at a supportive care program for prostate cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 11:4363–4373

Oliffe JL, Chambers S, Garrett B, Bottorff JL, McKenzie M, Han CS, Ogrodniczuk JS (2015) Prostate cancer support groups: Canada-based specialists’ perspectives. Am J Mens Health 9(2):163–172

Sharpley CF, Bitsika V, Wootten A, Christie DR (2014b) Does resilience ‘buffer’ against depression in prostate cancer patients? A multi-site replication study. Eur J Cancer Care 23(4):545–552

Owens OL, Jackson DD, Thomas TL, Friedman DB, Hebert JR (2015) Prostate cancer knowledge and decision making among African-American men and women in the Southeastern United States. Int J Mens Health 14(1):55–70

Social Care Institute for Excellence (2013) Co-production in social care: what is it and how to do it. Available at: https://www.scie.org.uk/publications/guides/guide51/ [Accessed 7th December 2020]

Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P et al (2016) Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf 25:509–517. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004315

Skolarus TA, Metreger T, Wittmann D, Hwang S, Kim HY, Grubb R, Gingrich JR, Zhu H, Piette JD, Hawley S (2020) Self-management in long-term prostate cancer survivors: a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 37:1326–1335

Wootten AC, Abbott JM, Meyer D, Chisholm K, Austin DW, Klein B, McCabe M, Murphy DG, Costello AJ (2015) Preliminary results of a randomised controlled trial of an online psychological intervention to reduce distress in men treated for localised prostate cancer. Eur Urol 68(3):471–479

Fogel J, RibisI KM, Morgan PD, Humphreys K, Lyons EJ (2008) The underrepresentation of African Americans in online cancer support groups. J Natl Med Assoc 100(6):705–712

Baruth M, Wilcox S, Saunders RP, Hooker SP, Hussey JR, Blair SN (2013) Perceived environmental church support and physical activity among Black church members. Health Educ Behav 40(6):712–720

Bowie JV, Bell NC, Ewing A, Kinlock B, Ezema A, Thorpe R, La Veist TA (2017) Religious coping and types and sources of information used in making prostate cancer treatment decisions. Am J Mens Health 11(4):1237–1246

National Health Service (2020). Getting NHS help when you need it during the coronavirus outbreak www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/05/C0525-getting-nhs-help-when-you-need-it-during-the-coronavirus-outbreak.pdf (accessed 7th December 2020).

Bennett G, Steinberg D, Stoute C, Lanpher M, Lane I, Askew S, Foley P, Baskin M (2014) Electronic health (e Health) interventions for weight management among racial/ethnic minority adults: a systematic review. Obes Rev 15:146–158

Majeed-Ariss R, Jackson C, Knapp P, Cheater FM (2015) A systematic review of research into black and ethnic minority patients’ views on self-management of type 2 diabetes. Health Expect 18(5):625–642

Chambers SK, Pinnock C, Lepore SJ, Hughes S, O’Connell DL (2011) A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for men with prostate cancer and their partners. Patient Educ Couns 85(2):e75–e88

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Mathew Dell for his support in accessing full-text articles for this review.

Funding

OB’s and SG’s roles are funded by Yorkshire Cancer Research as part of the TRANSFORM programme (Award reference number HEND405SPT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OB conceptualised the study. All authors contributed to developing the review protocol. SG and AW developed the search strategy with input from OB and OA. SG and AW ran the searches. OB, OA, MO and SG screened the articles for inclusion. OB, MO and OA contributed to the quality appraisal. OB, MO, SG and EDM contributed to data extraction. OB, AW, OA and EDM contributed to the data analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by OB and all authors revised and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable to this systematic review.

Consent to participate

Not applicable to this systematic review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable to this systematic review.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix. Search strategies for the databases

Appendix. Search strategies for the databases

Medline all via OVID

1 exp Prostatic Neoplasms/ (125179)

2 (prostat* adj2 (cancer* or neoplasm* or tumor or tumour* or malign* or carcinoma* or metasta* or oncolog*)).ti,ab,kw. (130717)

3 (Cancer Survivors/ or (cancer* adj2 survivor*).ti,ab,kw.) and prostat*.ti,ab,kw. (1163)

4 1 or 2 or 3 [prostate cancer concept] (158977)

5 (black* or african* or caribbean or african-caribbean* or afro-caribbean* or african american* or (ethnic adj3 minorit*)).ti,ab,kw. (293407)

6 African Americans/ or African Continental Ancestry Group/ or Caribbean region/ (88720)

7 exp Africa/eh (7754)

8 exp Caribbean Region/eh (3457)

9 (BME or BAME).ti,ab,kw. (2197)

10 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 [black men] (325900)

11 4 and 10 [black men and prostate cancer] (3572)

12 (psychosocial or psychological or social or (support adj2 group) or emotional).ti,ab,kw. (797782)

13 support*.ti,ab,kw. (1490116)

14 Self-Help Groups/ (8991)

15 exp psychological phenomena/ or mental competency/ or mental health/ or mental processes/ or exp counseling/ or directive counseling/ or distance counseling/ or pastoral care/ or sex counseling/ (1804972)

16 exp social support/ or Community Networks/ (75545)

17 counsel*.ti,ab,kw. (105651)

18 exp peer group/ (20316)

19 peer*.ti,ab,kw. (87815)

20 exp Information Seeking Behavior/ (2243)

21 adaptation, psychological/ or exp attitude/ or exp health knowledge, attitudes, practice/ (632939)

22 Patient Education as Topic/ (83949)

23 exp religion/ (59916)

24 exp spirituality/ (7218)

25 exp Faith-Based Organizations/ (1707)

26 religio*.ti,ab,kw. (39213)

27 faith*.ti,ab,kw. (16114)

28 ((message or discussion) adj3 (board or internet or online)).ti,ab,kw. (1239)

29 (chatroom* or (chat adj room*)).ti,ab,kw. (355)

30 (Online adj3 forum).ti,ab,kw. (446)

31 (Social media or Facebook or Twitter or blog*).ti,ab,kw. (13866)

32 exp Consumer Health Information/ (8748)

33 blogging/ or social media/ (7701)

34 or/12-33 (4131946)

35 11 and 34 [3 concepts SG/OB] (906)

Embase via OVID

Search strategy:

-

1.

exp prostate cancer/ (211392)

-

2.

(prostat* adj2 (cancer* or neoplasm* or tumor or tumour* or malign* or carcinoma* or metasta* or oncolog*)).ti,ab,kw. (198007)

-

3.

(cancer Survivor/ or (cancer* adj2 survivor*).ti,ab,kw.) and prostat*.ti,ab,kw. (2121)

-

4.

1 or 2 or 3 (248100)

-

5.

(black* or african* or caribbean or african-caribbean* or afro-caribbean* or african american* or (ethnic adj3 minorit*)).ti,ab,kw. (465185)

-

6.

exp black person/ or african american/ or african brazilian/ or african caribbean/ (101313)

-

7.

(BME or BAME).ti,ab,kw. (2168)

-

8.

5 or 6 or 7 (484101)

-

9.

4 and 8 (6274)

-

10.

(psychosocial or psychological or social or (support adj2 group) or emotional).ti,ab,kw. (1047909)

-

11.

support*.ti,ab,kw. (1921310)

-

12.

self help/ (13337)

-

13.

exp counseling/ (162741)

-

14.

exp mental health/ (150033)

-

15.

pastoral care/ (320)

-

16.

social support/ (88485)

-

17.

community care/ (54338)

-

18.

counsel*.ti,ab,kw. (153719)

-

19.

exp peer group/ (22854)

-

20.

peer*.ti,ab,kw. (109526)

-

21.

information seeking/ (3179)

-

22.

coping behavior/ (56629)

-

23.

attitude to health/ (109345)

-

24.

patient education/ (111879)

-

25.

exp religion/ (68674)

-

26.

faith-based organization/ (139)

-

27.

religio*.ti,ab,kw. (41632)

-

28.

faith*.ti,ab,kw. (19363)

-

29.

((message or discussion) adj3 (board or internet or online)).ti,ab,kw. (1967)

-

30.

(chatroom* or (chat adj room*)).ti,ab,kw. (484)

-

31.

(Online adj3 forum).ti,ab,kw. (653)

-

32.

(Social media or Facebook or Twitter or blog*).ti,ab,kw. (19832)

-

33.

blogging/ (322)

-

34.

social media/ (18187)

-

35.

consumer health information/ (3767)

-

36.

or/10-35 (3352544)

-

37.

9 and 36 (1285)

APA PsycINFO via OVID

Search strategy:

-

1.

exp Prostate/ and exp Neoplasms/ (1710)

-

2.

(prostat* adj2 (cancer* or neoplasm* or tumor or tumour* or malign* or carcinoma* or metasta* or oncolog*)).ti,ab,id. (3041)

-

3.

1 or 2 (3079)

-

4.

(black* or african* or caribbean or african-caribbean* or afro-caribbean* or african american* or (ethnic adj3 minorit*)).ti,ab,id. (131116)

-

5.

exp blacks/ or exp minority groups/ (64335)

-

6.

african cultural groups/ (2460)

-

7.

(BME or BAME).ti,ab,id. (249)

-

8.

4 or 5 or 6 or 7 (142948)

-

9.

3 and 8 (442)

-

10.

(psychosocial or psychological or social or (support adj2 group) or emotional).ti,ab,id. (1203016)

-

11.

support*.ti,ab,id. (644814)

-

12.

exp Group Counseling/ or exp Support Groups/ or exp Group Psychotherapy/ or exp Coping Behavior/ or exp Self-Help Techniques/ or exp Group Participation/ (92825)

-

13.

exp Counseling/ (76578)

-

14.

peers/ or peer counseling/ or peer relations/ (28053)

-

15.

coping behavior/ or spiritual well being/ or “stress and coping measures”/ (47506)

-

16.

exp Client Education/ (3921)

-

17.

exp religion/ (70047)

-

18.

exp spirituality/ (17404)

-

19.

exp Faith Based Organizations/ (313)

-

20.

(religio* or faith*).ti,ab,id. (83649)

-

21.

((message or discussion) adj3 (board or internet or online)).ti,ab,id. (1951)

-

22.

(chatroom* or (chat adj room*)).ti,ab,id. (703)

-

23.

(Online adj3 forum).ti,ab,id. (611)

-

24.

(Social media or Facebook or Twitter or blog*).ti,ab,id. (16960)

-

25.

exp Social Media/ (13310)

-

26.

exp Online Social Networks/ or exp Blog/ (7809)

-

27.

or/10-26 (1779294)

-

28.

9 and 27 (188)

CINAHL (ran: 17.01.2020)

1. (MH “Prostatic Neoplasms+”)

2. (prostat* N2 (cancer* OR neoplasm* OR tumor* OR tumour* OR malign* OR carcinoma* OR metasta* OR oncolog*))

3. ((MH “Cancer Survivors”) OR (cancer* N2 survivor*)) AND prostat*

4. 1 OR 2 OR 3

5. (black* OR African* OR Caribbean OR African-Caribbean* OR Afro-Caribbean* OR African American* OR (ethnic N3 minorit*))

6. (MH “Blacks”) OR (MH “African Continental Ancestry Group”) OR (MH “West Indies+/EH”)

7. (MH “Africa+/EH”)

8. Searched for this in line 6 instead

9. (BME or BAME)

10. 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 9

11. 4 AND 10

12. (psychosocial OR psychological OR social OR (support N2 group) OR emotion*)

13. support*

14. (MH “Support Groups”)

15. (MH “Psychological Processes and Principles+”) OR (No equivalent MH to mental competency) OR (MH “Mental Health”) OR (MH “Mental Processes”) OR (MH “Counseling+”) OR (No equivalent MH to directive counselling) OR (No equivalent MH to distance counselling) OR (MH “Spiritual Care”) OR (MH “Sexual Counseling”)

16. (MH “Support, Psychosocial+”) OR (MH “Community Networks”)

17. Counsel*

18. (MH “Peer Group”) Unable to explode

19. peer*

20. (MH “Information Seeking Behavior”) Unable to explode

21. (MH “Adaptation, Psychological”) OR (MH “Attitude+”) OR (MH “Health Knowledge”)

22. (MH “Patient Education”)

23. (MH “Religion and Religions+”)

24. (MH “Spirituality”) Unable to explode

25. (MH “Faith-Based Organizations”) Unable to explode

26. religio*

27. faith*

28. ((message OR discussion) N3 (board OR internet OR online))

29. (chatroom* OR (chat N1 room*))

30. (online N3 forum)

31. (Social media OR Facebook OR Twitter OR Blog*)

32. (MH “Consumer Health Information+”)

33. (MH “Blogs”) OR (MH “Social Media+”)

34. or/12-13

35. 11 AND 34

CINAHL — 553 results

WoS (ran 26.01.2020)

1. (prostat* NEAR/1 (cancer* OR neoplasm* OR tumor* OR tumour* OR malign* OR carcinoma* OR metasta* OR oncolog*))

2. ((cancer* NEAR/2 survivor*) AND prostat*)

3. 1 OR 2

4. (black* OR African* OR Caribbean OR African-Caribbean* OR Afro-Caribbean* OR African American* OR (ethnic NEAR/3 minorit*))

5. (BME OR BAME)

6. 4 OR 5

7. 3 AND 6

8. (psychosocial OR psychological OR social OR (support NEAR/2 group) OR emotion*)

9. support*

10. counsel*

11. peer*

12. religio*

13. faith*

14. ((message OR discussion) NEAR/3 (board OR internet OR online))

15. (chatroom* OR (chat NEAR/1 room*))

16. (online NEAR/3 forum)

17. (Social media OR Facebook OR Twitter OR Blog*)

18. or 8-17

19. 7 AND 18

Results — 803 (687 articles only)

Cochrane (ran 07.02.2020)

1. MeSH descriptor: [Prostatic Neoplasms] Explode all trees

2. (prostat* NEAR/2 (cancer* OR neoplasm* OR tumor* OR tumour* OR malign* OR carcinoma* OR metasta* OR oncolog*))

3. MeSH descriptor: [Cancer Survivors] this term only OR (cancer* NEAR/2 survivor*) AND prostat*

4. 1 OR 2 OR 3

5. (black* OR African* OR Caribbean OR African-Caribbean* OR Afro-Caribbean* OR African American* OR (ethnic NEAR/3 minorit*))

6. MeSH descriptor: [African Continental Ancestry Group] this term only OR MeSH descriptor: [Caribbean Region] explode all trees

7. MeSH descriptor: [Africa] explode all trees

8. BME OR BAME

9. 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8

10. 4 AND 9

11. (psychosocial OR psychological OR social OR (support NEAR/2 group) OR emotion*)

12. support*

13. MeSH descriptor: [Self-Help Groups] this term only

14. MeSH descriptor: [Psychological Phenomena] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Mental Competency] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Mental Health] this term only OR MeSH descriptor: [Mental Health] this term only OR MeSH descriptor: [Counseling] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Directive Counseling] this term only OR MeSH descriptor: [Distance Counseling] this term only OR MeSH descriptor: [Spirituality] this term only OR MeSH descriptor: [Sex Counseling] this term only

15. MeSH descriptor: [Psychosocial Support Systems] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Community Networks] this term only

16. Counsel*

17. MeSH descriptor: [Peer Group] explode all trees

18. Peer*

19. MeSH descriptor: [Information Seeking Behavior] explode all trees

20. MeSH descriptor: [Adaptation, Psychological] this term only OR MeSH descriptor: [Attitude] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice] this term only

21. MeSH descriptor: [Patient Education as Topic] this term only

22. MeSH descriptor: [Religion] explode all trees

23. MeSH descriptor: [Spiritual Therapies] this term only

24. MeSH descriptor: [Faith-Based Organizations] explode all trees

25. religio*

26. faith*

27. ((message OR discussion) NEAR/3 (board OR internet OR online))

28. (chatroom* OR (chat NEAR/1 room*))

29. (online NEAR/3 forum)

30. (Social media OR Facebook OR Twitter OR Blog*)

31. MeSH descriptor: [Consumer Health Information] explode all trees

32. MeSH descriptor: [Consumer Health Information] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Social Media] explode all trees

33. 11-32

34. 10 AND 33

Results — 232 (48 reviews, 176 trials, 8 protocols)

Scopus

( ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( prostat* W/2 ( cancer* OR neoplasm* OR tumor OR tumour* OR malign* OR carcinoma* OR metasta* OR oncolog* ) ) ) ) AND ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( black* OR african* OR caribbean OR african-caribbean* OR afro-caribbean* OR bme OR bame OR african AND american* OR ( ethnic W/3 minorit* ) ) ) ) AND ( ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( psychosocial OR psychological OR social ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( support W/2 group ) OR emotional* OR support* OR counsel* OR peer* OR religio* OR faith* ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( ( message OR discussion OR online ) W/2 ( board OR online OR internet OR forum* ) ) OR social AND media OR blog* OR facebook OR twitter ) ) ) AND NOT INDEX ( medline )

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bamidele, O.O., Alexis, O., Ogunsanya, M. et al. Barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilising post-treatment psychosocial support by Black men treated for prostate cancer—a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Support Care Cancer 30, 3665–3690 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06716-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06716-6