Abstract

Purpose

People diagnosed with cancer experience high distress levels throughout diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship. Untreated distress is associated with poor outcomes, including worsened quality of life and higher mortality rates. Distress screening facilitates need-based access to supportive care which can optimize patient outcomes. This qualitative interview study explored outpatients’ perceptions of a distress screening process implemented in an Australian cancer center.

Methods

Adult, English-speaking cancer outpatients were approached to participate in face-to-face or phone interviews after being screened by a clinic nurse using the distress thermometer (DT). The piloted semi-structured interview guide explored perceptions of the distress screening and management process, overall well-being, psychosocial support networks, and improvement opportunities for distress processes. Thematic analysis was used.

Results

Four key themes were identified in the 19 interviews conducted. Distress screening was found to be generally acceptable to participants and could be conducted by a variety of health professionals at varied time points. However, some participants found “distress” to be an ambiguous term. Despite many participants experiencing clinical distress (i.e., DT ≥ 4), few actioned referrals; some noted a preference to manage and prevent distress through informal support and well-being activities. Participants’ diverse coping styles, such as positivity, acceptance, and distancing, also factored into the perceived value of screening and referrals.

Conclusion and implications

Screening models only measuring severity of distress may not be sufficient to direct care referrals, as they do not consider patients’ varying coping strategies, external support networks, understanding of distress terminology, and motivations for accessing supportive care services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

People with a cancer diagnosis experience distress at higher levels than that of the general population during diagnosis and treatment [1]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) defines distress as “a multifactorial unpleasant experience of a psychological (i.e., cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, spiritual, and/or physical nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment” [2]. Surveys have indicated that up to half of people with a cancer diagnosis experience significant levels of distress [3,4,5,6]. If left untreated, this distress can lead to poor outcomes including decreased social functioning, increased intensity in physical symptoms, cognitive impairment, poor adherence to treatment, and reduced length of life [7,8,9,10]. As such, distress has been branded and is recognized internationally as the sixth vital sign [11, 12]. As distress levels peak during diagnosis and initial treatment stages [1], it is important to recognize and implement effective distress screening management processes within treatment facilities where there is an opportunity for early intervention.

Distress screening and management is beneficial, but implementation challenges remain: Timely and standardized distress screening if coupled with well-structured psychosocial referral systems can reduce patients’ emotional distress and improve their quality of life [3, 13, 14]. The benefits also extend to reduced physical symptoms and improved satisfaction with care and communication between patients and professionals [2]. There is also evidence that psychosocial screening reduces risk of emergency service use and hospitalization [15].

There remain challenges to the routine use of distress screening especially in time-poor clinical services. Firstly, there remains debate on the utility of single-item distress screening tools, such as the distress thermometer (DT) [16], especially without the use or availability of a well-structured referral pathway [16, 17]. Secondly, the implementation of distress screening programs is poorly reported, and it is likely that only select components of evidence-based approaches are being incorporated in health services, such as one-step screening or no rescreening [18, 19]. These two factors may have contributed to emerging reports that health professionals and services are unclear on the potential benefits of distress screening programs and thus unable to rationalize both the real and opportunity cost of yet another clinical activity [20].

Discrepancies between patient-reported acceptability and professional perceived acceptability exist: Australian data suggest the majority of cancer service representatives felt patients did not want to be asked questions about their distress, with 38% of health services reporting that they never, or rarely, screen for distress [21]. However, a quantitative study of 498 patients’ experiences with a distress screening program implemented in ten Dutch hospitals found that patients’ evaluations of the process were largely positive [22]. Opinions were more favorable in patients who more frequently completed the DT and problem checklist and were exposed to information about the tools and a discussion of potential referral options. In an Australian context, a cross-sectional study surveying callers (n = 100) to a cancer helpline reported that over 74% of callers diagnosed with cancer were comfortable with DT use [23]. Given the potential discrepancy between patient-reported acceptability and professional-reported perceived acceptability, there is a compelling demand for in-depth exploration on how patients experience distress screening within Australian cancer services. Qualitative research provides an opportunity to provide context and further insight into existing and new distress screening processes [24].

This qualitative study explored the lived experiences of distress screening and management from patient perspectives through the use of semi-structured interviews with people with a cancer diagnosis. The research aim of this study was to qualitatively evaluate a rapid distress screening process in very early implementation phases and to collate patient perspectives on the acceptability and role of standardized screening in managing their overall emotional well-being.

The study was conducted in a large tertiary outpatient cancer service during the rollout of a cloud-based distress screening tool. The distress screening procedure was designed by the health service to be rapid, administered at each clinical appointment, and integrated into electronic medical records. This study recruited an opportunity sample of the patients screened and provides insight into how patients’ perceive the value and approach of brief screening models in Australian health services as part of their overall cancer journey.

Methods

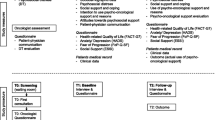

Study design and recruitment

The qualitative interview study is reported in accordance with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative (COREQ) guidelines [25]. Patients were approached by a clinic nurse and invited to participate between May and July 2019. The screening pathway included asking all cancer outpatients to complete the DT and problem checklist on a kiosk before their appointment. The DT has an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress) [3]. The problem checklist prompts the patient to identify sources of distress using a problem list. Each item is directly related to one of five domains: practical, relationship, emotional, spiritual, or physical. Inclusion criteria included being at least 18 years of age, proficient in English, and having received a cancer diagnosis. In line with best practice guidelines that recommend all outpatients are screened for distress regardless of demographic or clinical characteristics, there were no exclusion criteria applied to time since diagnosis, treatment status, or cancer type for the interviews. The research team recruited participants using a purposive sampling approach to ensure representation of gender and a broad age range. The project was approved by Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (2018/ETH00520).

Data collection

A research team member (MC) with experience in qualitative research conducted 19 semi-structured interviews (30–45 min). Interviews were conducted face to face (n = 4) or via telephone (n = 15). The semi-structured interview guide included questions pertaining to perceptions of the distress screening process, emotional well-being, reasons for referral uptake/non-uptake, experiences of accessing new or existing professional and personal psychosocial support networks, and ways the distress screening and management process could be improved. Individuals were asked medical and demographic questions during the interview to contextualize findings. Individuals were also asked to complete the DT at time of interview as a way to prompt recall of their in-clinic experience, and in the case, they were asked other screening questions by other services. Participants’ DT score also provided context when discussing experiences, for example, gaps in referrals for moderately to severely distressed individuals or perceived value of screening for mildly distressed individuals. The interview guide was pilot tested with three members of a consumer advisory panel.

The research team considered data collection to have reached saturation when information became repetitive or no new information was being obtained; this was agreed upon through review of transcripts and field notes and discussion with the research team (MC, KM, EF) [26]. Multiple meetings to review transcripts, comprehensiveness of codebook, and emergence of new themes (if any) were held over a 2-month time period. All participants declined the opportunity to review their transcripts.

Data analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and coded by two team members (KM, MC) using NVivo 12 qualitative data analysis software. Using an inductive thematic analysis framework [27], a sample of transcripts was open-coded prior to collaboratively developing a codebook. The remaining transcripts were coded in batches using an iterative process of discussion and codebook refinement. Following coding, clear themes were identified and related back to data extracts to ensure coherence.

Results/findings

Of the 39 patients invited to the study, 29 eligible individuals consented to be contacted by the research team. The 10 individuals who declined to be contacted cited a lack of time or the perception that they had little to contribute to the study. Of the remaining 29 participants who consented to contact, 19 consented to interviews prior to saturation being reached. The demographic characteristics of 19 participants are listed in Table 1.

Four overarching themes were derived from the data. In talking about distress screening procedures, many participants expanded their discussion to include their attitudes toward distress, well-being, styles of coping, and understanding of the term “distress.”

Attitudes toward formalized screening and logistics

Quotes are provided for each of the subthemes in Table 2.

Acceptability

The majority of participants reported both the mode of in-clinic electronic delivery and the experience of distress screening as being acceptable and appropriate even if not directly relevant to themselves. The DT was described positively as short, and participants appeared happy to have this process included as part of routine care. The process was perceived to facilitate communication, with participants suggesting it would help them to be more honest about their distress than if they had been asked a more general question about well-being.

However, some participants did not appreciate completing the DT on a computer. One participant felt that responses would be inaccurate and would not be acted on if asked using a computerized kiosk, preferring human interaction.

Distress screening logistics

No single health professional was identified consistently as to who should be responsible for screening for distress; nurses, GPs, oncologists, social workers, and counselors were all suggested by participants. Participants had varying views on timing and recurrence of distress screening. Some felt that routine screening at repeated time points was appropriate. However, for some patients, distress screening was seen as not useful at initial diagnosis or beginning of treatment, when they were feeling overwhelmed with information.

Managing distress and well-being

This theme encompassed discussions around participants’ awareness of their own distress and the desire for and access to services to assist. This conversation arose as part of discussing the sequential steps of the distress management pathway: screening, discussion, referral, and service use. Independent of their distress severity or health service use, participants also discussed self-initiated activities of daily living or leisure as a way to improve overall well-being. Quotes are provided for the subthemes in Table 3.

Discussion, referral, and service use within health settings

When prompted to speak about supports for management of their distress, many felt that a referral to formal support services such as a psychologist, social worker, or support group was not relevant to them. Although these participants stated that they did not believe that a referral would be useful to them, they nevertheless endorsed distress screening as a potentially important communication tool in their relationship with health professionals. At the same time, participants strongly emphasized the need for open communication with cancer nurses outside of a more formalized pathway, and explanations of the various forms of support were essential when discussing referrals.

A small number of participants reported recognizing that they needed support and would have welcomed a referral. One patient suggested that although they did not feel they needed formalized support at this stage of their diagnosis, it could be helpful if their health declined.

Other forms of support to manage distress levels

Participants spoke of the importance of various types of support, social, spiritual, and formal/clinical support when managing distress. For some participants, this was seen as just as important as talking to a professional about their feelings. The need for support was also evident in discussion about practical assistance such as getting to appointments, cooking meals, and house cleaning. One participant suggested that informal social support can wane after treatment has finished.

Activities for well-being and reducing distress

Participants found a variety of strategies and activities helpful in promoting overall well-being and reducing distress. The majority of these were leisure activities which would not necessitate health professional involvement but could be facilitated within community services or groups. Examples included exercise, art, spiritual activities, and volunteering to help others. These activities were largely characterized as providing distraction and keeping busy to keep one’s mind off the cancer. One participant found fulfillment in using their hobbies to give back to the people who support them. Experiences of fulfillment and rewarding social interactions were also shared by those who kept busy through volunteer work.

Styles of coping with cancer

In talking about distress, this led many participants to talk about their attitudes toward their cancer diagnosis more broadly. Representation of different styles of coping emerged from this discussion. Subthemes included being positive, acceptance, and distancing; quotes are provided in Table 4.

Being positive

The first clear style of coping that appeared was being positive. Although centered on positive belief, this attitude was expressed as though it were an active stance, a committed notion of “fighting,” with the implication that not doing so (being positive) could lead to worse outcomes.

Acceptance

Another approach that participants described was acceptance.

While being a common thread, participants’ reasons for this acceptance were different: from knowing that family would be okay to acknowledging the life that they have already had.

Distancing

The final subtheme in styles of coping involved not thinking about the cancer. For some people, this also meant not talking about the cancer, or even naming it.

Understanding of distress

Although we provided participants the NCCN definition of distress in our interviews, and they had recently been through the process of distress screening, there was some lack of understanding as to the meaning of distress. Participants separated their experiences of anxiety from the term “distress.” While distress is defined within research and clinically as encompassing common and normal feelings, participants saw this term as representing the more severe end of this continuum (see Table 5).

Discussion

This qualitative exploration revealed important information on the experience of brief distress screening among a group of people with cancer who had been screened as part of their usual appointment in an Australian hospital cancer clinic. This distress screening program is similar to other brief programs internationally [28, 29] and uses one of the most common screening tools (the distress thermometer) [21]. When considering the overall acceptability of the screening program, participants contextualized their distress within broader themes of coping, support from their personal networks, and questioned the definition of distress.

Distress screening was generally acceptable to cancer outpatient participants

It is widely recognized that cancer diagnosis and treatment can significantly affect patients’ well-being, such that distress during cancer is now considered the sixth vital sign [11, 12]. An issue of clinical importance is that, despite the implementation of distress screening and the established evidence base for the effectiveness of psychological interventions to reduce distress, supportive care referral is generally low [30]. This has led to investigations to determine why this is the case. The findings of this study reaffirm that patients generally find distress screening to be acceptable although not always personally applicable [31]; furthermore, some participants did not perceive formalized supportive care services to be relevant or valuable.

The logistics of distress screening, particularly the timing and health professional involved, showed variable preferences. For some participants, if presented too soon or without sufficient explanation, distress screening was seen as not useful. In some cases, it was reported as overwhelming amidst the start of treatment with information and appointments. This echoes other study findings in which patients and clinicians felt screening was more effective middle to late in the cancer trajectory rather than early [32].

Participants endorsed distress screening as the role of numerous health professionals; no single consistent clinician type was identified, and our participants’ views demonstrate differing preferences for which clinicians should address distress. Clinical guidelines recommend that everyone responsible for the patient care should be at least aware of how the patient is progressing through the distress screening and management pathway [13]. However, an implementation barrier often cited is confusion as to roles and responsibilities in this process and the lack of time and confidence to ask about distress and provide follow-up [18, 20]. Developing specific roles and responsibilities for the members of the multidisciplinary team along with training modules would facilitate distress screening implementation models. This principle of allocating responsibility should also extend to referrals, whereby a member of the healthcare team ensures need-based referrals are made and patients are empowered to action the referral.

Patients may not perceive supportive care referrals as personally relevant

Participants identified social supports such as family and friends to be paramount in providing support throughout their cancer diagnosis and treatment. For some participants, this was cited as being more important than formalized support. This may be one reason for low referral uptake, particularly among those who do not perceive themselves as distressed. Conversely, there was another group who felt that they did not want to burden their friends and family but saw value in talking about their experience. Availability and willingness to draw upon family and social support might be an important consideration when considering and presenting referral to patients. This notion has been explored previously in a study that highlighted that receptivity to referral is a separate issue from distress levels [33].

A further study suggests that referral uptake is driven, in part, by patients’ conceptualizing psychological support as preventative to worsening distress as opposed to reactive when distress is already severe [34]. Knowledge of the benefits of support was also associated with increased referral uptake [30]. Within our study, participants often did not feel supportive care services were required because they did not feel distressed “enough.” It is possible that this brief distress screening model did not provide patients with information on the support services nor the motivational coaching required to action supportive care referrals. In order to maximize the utility of screening, health professionals must confidently action screening results and empower the distressed patient to recognize the personal benefit of supportive care. This may require a paradigm shift as many health professionals are focused on the biomedical model of care, along with dedicated resources to provide timely access to embedded supportive care services [35]. The lack of training to confidently identify and manage distress is a common barrier reported by cancer professionals [36].

The utility of distress screening across different patient coping styles

Interview participants noted oppositional coping styles, acceptance, and positivity versus distancing. This finding aligns with previous studies. For example, a qualitative study emphasized cognitive distancing as a coping strategy among cancer patients [37]. These different approaches have implications for both the method in which distress is introduced, measured, and then discussed by health professionals [37].

Individuals with distancing coping strategies may choose to opt-out of distress screening and provide a non-representative answer (i.e., provide a lower score), or health professionals may be reluctant to continue discussions about emotional well-being. A qualitative study exploring general practitioners’ perceptions of assessing distress in cancer patients identified “denial” as a barrier to implementing further psychosocial assessment [38]. A study of communication distancing with women with breast cancer suggests that coaching distant patients and their loved ones to have difficult conversations about emotional well-being may be an important psychosocial intervention to enhance coping capacity [39].

Acknowledging patients’ coping strategies is a complex component of providing person-centered care which requires patients’ preferences to be respected. For example, previous studies have demonstrated distant coping styles were positively associated with quality of life, whereas emotion-focused styles were negatively associated with quality of life [40]. Other studies have suggested distant thinking was related to worse long-term outcomes [41]. While this long-standing debate on the utility of distant coping continues [41], there is little guidance specifically on how to coach patients who are highly distressed and distant to utilize supportive care interventions. Furthermore, it would be valuable to explore the acceptability of psychosocial screening and uptake of subsequent referrals across coping styles in a larger sample using validated measures, such as the Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer or Brief-Cope Inventory. Also, it is important to acknowledge that while the coping styles have been presented as different approaches, it is likely that they are not mutually exclusive; patients may utilize different strategies depending on their evolving needs and experiences.

Concept and definition of distress

Nomenclature surrounding mental health is challenging, and the term “distress” was selected by tool developers as it was perceived to be less stigmatizing than “psychological” or “emotional” and therefore more acceptable [3]. However, the term distress can have different meanings across different disciplines and areas of life [42]. As a one-item tool, the DT is perceived as efficient in quickly capturing individuals who are potentially experiencing distress. Nevertheless, it is paramount that those completing the tool have a clear understanding of the definition of distress. So that tools remain brief, it may be ideal to have a quick orientation to the concept of distress before the first administration or provide an abbreviated patient resource with a more extensive definition [43]. Future studies could explore the effect and patient experience of these suggestions.

Limitations

This research may have been affected by selection bias. As part of the recruitment process, patients in the clinic were not invited to participate if they declined completing the DT. Other patients declined to participate citing not feeling they could contribute to a discussion about distress. It is possible that patients who declined the screening process or study participation may have differed from the study participants in their perceptions of being asked about distress, managing their diagnosis and ways of coping.

The study also included individuals who were newly diagnosed and those who were more than 2 years post diagnosis. Although this aligns with universal screening of all individuals in contact with the health service and the majority of our participants reported some level of distress, it is possible that individuals reflected differently on their experience of distress screening. We also did not ask participants if they had completed other emotional well-being screening questions or had previously completed the DT in other settings. As patient-reported outcome and experience measures become more integrated into health services, it is possible that patients particularly those who had been diagnosed more than 2 years ago had become more comfortable and familiar with completing these exercises.

Additionally, none of the participants in this study identified as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent. Although the DT is a validated tool, acceptability of screening tools can vary across and within cultures. Distress in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations remains under-researched [44], and further studies should consider acceptability and cultural safety in these populations.

It is important to note that this study discussed only one form of available distress screening methods which was not supported by a formalized referral pathway at the time of screening, though the cancer service did have access to a psycho-oncology team.

Conclusions

This study found patients are generally accepting of in-clinic distress screening, and brief screening tools are important triggers or “red flags” for subsequent discussions. However, just as our study participants expanded discussions of distress screening to broader concepts of coping and support, so must health professionals. Our results suggest that in order for patients’ distress to be accurately captured and supportive care to be provided, clinicians and our systems must consider patients’: varying coping strategies, external support networks, understanding of terms, and motivations for accessing supportive care services. More research is needed to elucidate how we gather this information and how it impacts the distress screening process.

Data availability

NA.

Code availability

NA.

References

Breen SJ, Baravelli CM, Schofield PE, Jefford M, Yates PM, Aranda SK (2009) Is symptom burden a predictor of anxiety and depression in patients with cancer about to commence chemotherapy? Med J Aust 190(S7):S99-104

Riba MB, Donovan KA, Andersen B et al (2019) Distress management, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 17(10):1229–1249. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2019.0048

Michelle BR, Kristine AD, Barbara A et al (2019) Distress management, Version 3.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 17(10):1229–1249

Mehnert A, Hartung TJ, Friedrich M et al (2018) One in two cancer patients is significantly distressed: prevalence and indicators of distress. Psychooncology 27(1):75–82

Jacobsen PB, Ransom S (2007) Implementation of NCCN distress management guidelines by member institutions. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 5(1):99–103

Reilly CM, Bruner DW, Mitchell SA et al (2013) A literature synthesis of symptom prevalence and severity in persons receiving active cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 21(6):1525–1550

Skarstein J, Aass N, Fosså SD, Skovlund E, Dahl AA (2000) Anxiety and depression in cancer patients: relation between the hospital anxiety and depression scale and the European Organization for research and treatment of cancer core quality of life questionnaire. J Psychosom Res 49(1):27–34

Fann JR, Thomas-Rich AM, Katon WJ et al (2008) Major depression after breast cancer: a review of epidemiology and treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 30(2):112–126

Snyder CF, Garrett-Mayer E, Brahmer JR et al (2008) Symptoms, supportive care needs, and function in cancer patients: how are they related? Qual Life Res 17(5):665–677

Russ TC, Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Starr JM, Kivimäki M, Batty GD (2012) Association between psychological distress and mortality: individual participant pooled analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies. BMJ 345:e4933

Holland JC, Bultz BD (2007) The NCCN guideline for distress management: a case for making distress the sixth vital sign. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 5(1):3–7

Fradgley EA, Bultz BD, Kelly BJ, Loscalzo MJ, Grassi L, Sitaram B (2019) Progress toward integrating Distress as the Sixth Vital Sign: a global snapshot of triumphs and tribulations in precision supportive care. J Psychosoc Oncol Res Pract 1(1):e2

Butow P, Price MA, Shaw JM et al (2015) Clinical pathway for the screening, assessment and management of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: Australian guidelines. Psychooncology 24(9):987–1001

Carlson MA, Booth K, Byrnes E, Paul C, Fradgley EA (2020) Pin-pointing service characteristics associated with implementation of evidence-based distress screening and management in australian cancer services: data from a crosssectional study. J Psychosoc Oncol Res Pract 2(2):e20

Brad Z, Karen K, Deborah B et al (2017) A practice-based evaluation of distress screening protocol adherence and medical service utilization. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 15(7):903–912

Coyne JC (2013) Second thoughts about implementing routine screening of cancer patients for distress. Psycho-Oncologie 7(4):243–249

Dekker J, Braamse A, Schuurhuizen C et al (2017) Distress in patients with cancer – on the need to distinguish between adaptive and maladaptive emotional responses. Acta Oncol 56(7):1026–1029

McCarter K, Fradgley EA, Britton B, Tait J, Paul C (2020) Not seeing the forest for the trees: a systematic review of comprehensive distress management programs and implementation strategies. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 14(3):220–231

Taylor J, Fradgley EA, Clinton-McHarg T, Roach D, Paul CL (2020) Distress screening and supportive care referrals used by telephone-based health services: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 28(5):2059–2069

Rankin NM, Butow PN, Thein T et al (2015) Everybody wants it done but nobody wants to do it: an exploration of the barrier and enablers of critical components towards creating a clinical pathway for anxiety and depression in cancer. BMC Health Serv Res 15(1):28

Fradgley EA, Byrnes E, McCarter K et al (2020) A cross-sectional audit of current practices and areas for improvement of distress screening and management in Australian cancer services: is there a will and a way to improve? Support Care Cancer 28(1):249–259

van Nuenen FM, Donofrio SM, van de Wiel HBM, Hoekstra-Weebers J (2018) Cancer patients’ experiences with and opinions on the process ‘Screening of Distress and Referral Need’ (SDRN) in clinical practice: a quantitative observational clinical study. PLoS One. 13(6):e0198722

Linehan K, Fennell KM, Hughes DL, Wilson CJ (2017) Use of the distress thermometer in a cancer helpline context: can it detect changes in distress, is it acceptable to nurses and callers, and do high scores lead to internal referrals? Eur J Oncol Nurs 26:49–55

Braun V, Clarke V (2014) What can “thematic analysis” offer health and well-being researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being 9(1):26152

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6):349–357

Walker JL (2012) Research column. The Use of Saturation in Qualitative Research. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs 22(2):37–41

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Butow P, Shaw J, Shepherd HL et al (2018) Comparison of implementation strategies to influence adherence to the clinical pathway for screening, assessment and management of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients (ADAPT CP): study protocol of a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Cancer 18(1):1077

Dudgeon D, King S, Howell D et al (2012) Cancer Care Ontario’s experience with implementation of routine physical and psychological symptom distress screening. Psychooncology 21(4):357–364

Tondorf T, Grossert A, Rothschild SI et al (2018) Focusing on cancer patients’ intentions to use psychooncological support: a longitudinal, mixed-methods study. Psychooncology 27(6):1656–1663

Howell D, Olsen K (2011) Distress-the 6th vital sign. Curr Oncol 18(5):208–210

Biddle L, Paramasivan S, Harris S, Campbell R, Brennan J, Hollingworth W (2016) Patients’ and clinicians’ experiences of holistic needs assessment using a cancer distress thermometer and problem list: A qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 23:59–65

Sylvie DL, Brian K, Allison B et al (2014) Insights into preferences for psycho-oncology services among women with gynecologic cancer following distress screening. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 12(6):899–906

Tondorf T, Grossert A, Rothschild SI et al (2018) Focusing on cancer patients’ intentions to use psychooncological support: a longitudinal, mixed-methods study. Psychooncology 27:1656–1663

Zucca A, Sanson-Fisher R, Waller A, Carey M, Fradgley E, Regan T (2015) Medical oncology patients: are they offered help and does it provide relief? J Pain Symptom Manage 50(4):436–444

Granek L, Nakash O, Ariad S, Shapira S, Ben-David M (2018) Oncologists’ identification of mental health distress in cancer patients: strategies and barriers. Eur J Cancer Care 27(3):e12835

Kvåle K (2007) Do cancer patients always want to talk about difficult emotions? A qualitative study of cancer inpatients communication needs. Eur J Oncol Nurs 11(4):320–327

Carolan CM, Campbell K (2016) General practitioners’ ‘lived experience’ of assessing psychological distress in cancer patients: an exploratory qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care 25(3):391–401

Yu Y, Sherman K (2015) Communication avoidance, coping and psychological distress of women with breast cancer. J Behav Med 38(3):565–577

Shakeri J, Kamangar M, Ebrahimi E, Aznab M, Shakeri H, Arman F (2015) Association of coping styles with quality of life in cancer patients. Indian J Palliat Care 21(3):298–304

Lauriola M, Tomai M (2019) Biopsychosocial correlates of adjustment to cancer during chemotherapy: the key role of health-related quality of life. ScientificWorldJournal 2019:9750940–9750940

Ridner SH (2004) Psychological distress: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 45(5):536–545

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2020) NCCN guidelines for patients: distress during cancer care. https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/distress-patient.pdf. Accessed 23 Nov 2021

Garvey G, Cunningham J, Janda M, Yf He V, Valery PC (2018) Psychological distress among Indigenous Australian cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 26(6):1737–1746

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Peter Troke and Prof. Anthony Proietto for their assistance in facilitating this research. We also acknowledge all participants for sharing their time, knowledge, and experiences with the research team. The authors are thankful to the Hunter Cancer Research Alliance (HCRA) Consumer Advisory Panel members who provided valuable insight into the research design. The authors also acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land upon which we work, the Awabakal people, and pay our respects to elders past and present.

Funding

This project is a component of a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Translation Advancement Incentive (TAI) awarded to Prof Amanda Baker accompanying her NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (APP1135901). Dr Elizabeth Fradgley is supported by a CINSW ECR Fellowship and receives infrastructure support from the Hunter Medical Research Institute. Melissa Carlson is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program. For the remaining authors, no conflicts are declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Melissa Carlson and Kristen McCarter. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Melissa Carlson, Kristen McCarter, and Elizabeth Fradgley, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This project was approved by Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (2018/ETH00520).

Consent to participate

All participants provided written consent to partake in this research.

Consent for publication

All participants provided written consent for the research to be published.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McCarter, K., Carlson, M.A., Baker, A.L. et al. A qualitative study investigating Australian cancer service outpatients’ experience of distress screening and management: what is the personal relevance, acceptability and improvement opportunities from patient perspectives?. Support Care Cancer 30, 2693–2703 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06671-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06671-2