Abstract

Purpose

To examine the evidence of the feasibility, acceptability, and potential efficacy of online supportive care interventions for people living with and beyond lung cancer (LWBLC).

Methods

Studies were identified through searches of Medline, EMBASE, PsychINFO, and CINAHL databases using a structured search strategy. The inclusion criteria (1) examined the feasibility, acceptability, and/or efficacy of an online intervention aiming to provide supportive care for people living with and beyond lung cancer; (2) delivered an intervention in a single arm or RCT study pre/post design; (3) if a mixed sample, presented independent lung cancer data.

Results

Eight studies were included; two randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Included studies reported on the following outcomes: feasibility and acceptability of an online, supportive care intervention, and/or changes in quality of life, emotional functioning, physical functioning, and/or symptom distress.

Conclusion

Preliminary evidence suggests that online supportive care among individuals LWBLC is feasible and acceptable, although there is little high-level evidence. Most were small pilot and feasibility studies, suggesting that online supportive care in this group is in its infancy. The integration of online supportive care into the cancer pathway may improve quality of life, physical and emotional functioning, and reduce symptom distress. Online modalities of supportive care can increase reach and accessibility of supportive care platforms, which could provide tailored support. People LWBLC display high symptom burden and unmet supportive care needs. More research is needed to address the dearth of literature in online supportive care for people LWBLC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death internationally for both men and women [1]. It is a debilitating disease which has a large effect on quality of life (QoL) [1]. Though the median life expectancy for people diagnosed with lung cancer remains poor, advances in screening and curative treatments for lung cancer have contributed to the 9% reduction in mortality over the last decade and extended life expectancy [2, 3]. Increasing survival rates have been reported [4, 5], however, curative treatments can elicit a myriad of adverse physiological and psychological effects which can reduce QoL (e.g. fatigue, dyspnea, and depression) [1, 6, 7]. In fact, people living with and beyond lung cancer (LWBLC) have reported greater unmet psychological and physiological needs in comparison to other types of cancer [8, 9]. Unmet needs are those needs which do meet the level of support required for optimal health [10].

Supportive care can be defined as care that helps an individual living with and beyond cancer and/or their immediate family or caregivers cope throughout the treatment pathway, from diagnosis to continuation through the illness or death [5]. Evidence suggests that supportive care needs for people LWBLC have noticeably increased [11]. A systematic review examining the supportive care needs of people living with lung cancer reported nine distinct domains of supportive care needs: physical, psychological, spiritual, cognitive, communication, social, daily living, practical, and informational [12]. The nine domains highlight the considerable burden among people LWBLC and the importance of supportive care interventions.

The internet and digital technology have become an important resource used within the oncology community, both for people living with and beyond cancer and oncology professionals [3]. Utilizing digital technology to deliver oncological supportive care has attracted significant interest over the recent years [13,14,15], with the potential to deliver tailored, inexpensive care while achieving mass reach [16, 17].

Thus far, online health and supportive care services have largely focused on breast and prostate cancer [17, 18]. Few online supportive care platforms exist for people LWBLC, despite the need and potential benefits to patients [13,14,15]. Though reviews have explored the use of online and digital interventions among mixed cancer types [17, 19], specific cancer-related needs and symptom burden vary considerably [17]. Those who live five or more years post-lung cancer diagnosis are referred to as ‘Long-Term Lung Cancer Survivors’ (LTLCS) [20]. In comparison to their age-matched counterparts from other types of long-term cancer survivors, LTLCS display the lowest QoL [20, 21]. In the USA, an estimated one in four LTLCS are living with significant restrictions in physical functioning and depressive mood symptoms [20].

McAlpine et al. (2015) critically examined the efficacy of online interventions for cancer patients, highlighting the uncertainty of the benefits with mixed results [17]. Among the 14 studies included in the McAlpine review, the majority focused solely on breast cancer with only three studies independently reporting lung cancer, head and neck cancer, prostate cancer, and four reporting mixed cancer types. McAlpine and colleagues illustrate that though there is increasing interest in online technology within oncology care, there is a lack of literature regarding efficacy. This may be partially due to the small portion of studies which present a quantifiable and a clinically meaningful evidence-base [17].

To appropriately develop and appraise literature for people LWBLC, cancer type must be used as a moderator, allowing specific evaluation on the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of online technologies for people LWBLC. Thus, this review aims to examine the evidence of the feasibility, acceptability, and potential efficacy of online supportive care interventions for people LWBLC. For the purpose of this review, online supportive care will be defined as interventions delivered using online mediums which aim to meet a person’s physical, social, informational, spiritual, practical, and/or psychological needs during the diagnostic, treatment, and follow-up phases of the cancer spectrum [22]. This review will examine individuals LWBLC. For the purpose of this study, LWBLC is any individual who has had a diagnosis of lung cancer or cancer within the lungs.

Methods

The review adheres to the reporting of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [23]. A standardised data extraction form [24] was adapted for the extraction and review of all data. Ethical approval was not required.

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility of studies was based upon inclusion and exclusion criteria developed a priori (PROSPERO ID: CRD42020171847). A study’s eligibility was based on whether it met the following conditions: (1) examined the feasibility, acceptability, and/or efficacy of an online intervention aiming to provide supportive care for people LWBLC; (2) single arm or RCT study pre/post design; (3) if a mixed sample, presented independent lung cancer data. Studies were excluded based on the following conditions: (1) mixed sample data was presented with no individual lung cancer data (mixed cancer types); (2) articles were not provided in English; (3) full text articles were not available.

Search strategy

The databases EMBASE, Medline, PsychINFO via OVID, and CINAHL via EBSCOhost were searched from their inception up to April 2020. MeSH terms were identified for the key concepts in Medline and the equivalent adapted for subsequent databases. The development of the search strategies, per database, was completed with the assistance of an Information Specialist (SG). Boolean operators were used to combine MeSH terms and keyword terms to develop a pilot strategy. The pilot strategy was executed in Medline and refined to ensure the relevance of the search output (see Online Resource 1). The search strategy for Medline, EMBASE, and PsycINFO focused on the following: lung cancer AND (Internet OR social media/online supportive care interventions). Whereas the terms in CINAHL were lung cancer AND social media platforms AND internet platforms. All searches were conducted by a single author (JC).

Study selection

All articles identified through the database searches were exported to a citation management software (EndNote, X9.2), wherein duplicates were removed. Rayyan citation screening software was used post-deduplication by two authors (JC and MPa) to screen titles and abstracts against pre-specified inclusion criteria. Disagreements were discussed and resolved by mutual consensus.

Data extraction and methodological quality assessment

Data from the included studies were extracted using a data extraction form, which was developed by the research team following a recommended template [24]. Data regarding study setting, participant characteristics, study design, intervention procedure, outcome results, and findings relating to feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of the intervention were extracted. The extraction form was piloted by two of the authors (JC and CF) to ensure it captured all relevant information on paper. No changes were made, and the remaining articles were extracted independently by JC, with 100% of the articles also extracted by a second author (MPa). The two authors had one disagreement regarding the extraction of qualitative text from one article [15], but was resolved by mutual consensus with input from a third author (CF).

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed via the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields [25]. This tool provides independent subscales for methodological assessment of qualitative and quantitative data. The tool allows for a broad assessment of quantitative studies including non-randomised, pilot, and feasibility studies. The tool selected for this review was with consideration of the study designs [26, 27] and prior literature [28, 29] in mind. The tool was chosen based on the importance of including a wide range of study designs, as it has been noted that within single study designs, aspects such as feasibility, reliability, validity, and utility are variables often unmeasured [30].

Study quality was rated in accordance with the following accepted scoring methods, > 80% “strong”, 71–79% “good”, 50–70% “adequate”, and < 50% “poor” [28, 29, 31]. If any uncertainty surrounding the initial assessment of the level of bias within a study was noted between the two authors, a member of the research team (MPa) assisted in reaching a consensus. Studies were not excluded from the synthesis of this review based on the rating of study quality.

Outcomes

The following outcomes were assessed to ascertain feasibility: (1) recruitment and retention rates, (2) recruitment barriers, (3) intended implementation, (4) cost of implementation. Outcomes assessing acceptability were: (1) acceptability and satisfaction, (2) intervention adherence rates, (3) intervention burden, (4) noted adverse effects. Efficacy was reported for RCTs only. The outcomes relating to efficacy was assessed by the effect of supportive care relative to the comparison group for the outcome measured.

Results

Study selection

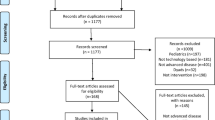

A flow chart detailing the study selection process is presented in Fig. 1. A total of 2468 publications were identified from the following databases: Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. One additional article was identified through hand searching. After the removal of duplicates, 2111 articles were included in title and abstract screening and 128 studies were included in full text screening. Finally, eight articles were acknowledged as meeting the eligibility criteria and were included in data extraction.

PRISMA flow diagram [23]

Risk of bias/methodological assessment

Findings from the methodological quality assessment are presented for quantitative measures in Table 1 and qualitative measures in Table 2. Based on the assessment conducted independently by two reviewers (JC and CF), six studies were assessed for quantitative methods [32,33,34,35,36,37] and two studies assessed for both quantitative and qualitative methods [13, 15]. Based on quantitative methods, eight studies were rated as strong [13, 15, 32,33,34,35,36,37]. For qualitative methods, one study was rated strong [15] and one adequate [13].

Study characteristics

This review included two RCTs [33, 36] and six pilot and feasibility studies [13, 15, 32, 34, 35, 37]. The included studies were carried out in seven different countries, (two in South Korea [33, 34], one each in the USA [37], France [32], Canada [35], Netherlands [13], Taiwan [36], and the UK [15]). Of the eight studies, seven comprised solely of individuals LWBLC [13, 15, 32,33,34,35,36], one study explored both carers and individuals living with and beyond gastrointestinal cancer or lung cancer [37]. Specifically, of the studies focusing on independent lung cancer populations, four focused on Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) [13, 33, 34, 36], one focused on surgical excision [32], one explored patients with lung cancer, receiving a specific course of radiotherapy [15], and unresectable thoracic neoplasia [35].

Five studies reported the cancer disease stage, ranging from I to IVb [32,33,34,35,36], one study reported the ASA Physical Status Classification System (ASA) [37], and two studies did not report the stage of cancer [13, 15]. Treatment types reported were chemotherapy [34,35,36], thoracic radiotherapy [15], and maintenance therapy [32]. One study reported the extent of surgery participants had [13] and two did not report any treatment information [33, 37]. Further information regarding the study characteristics can be found in Table 3.

Intervention characteristics

The three primary domains explored within the eight studies were education (n = 1) [36], physical activity and exercise [13, 35, 37] (n = 3), and self-evaluation and symptom monitoring (n = 2) [15, 32]. Two studies of the eight combined exercise and symptom management (n = 2) [33, 34].

One study focused on investigating the impact of a web-based health education program on global quality of life, quality of life-related function, and symptom distress over a 3-month period [36]. Another 3-month intervention explored the outcomes of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) regarding exercise capacity, dyspnea symptoms, and QoL in adult receiving treatment for NSCLC [34]. One of the interventions explored the use of tele-health in two mediums: ambulant symptom and physical activity monitoring (S&PAM) and a web-accessible home-based exercise program (WEP) [13].

The majority of the supportive care was delivered via mobile phone-based applications (n = 4) [13, 15, 33, 34], with other mediums including websites (n = 1) [36], web-based applications (n = 1) [32], video conferencing (n = 1) [37], and a Tele-Rehab Station (n = 1) [35]. The Tele-Rehab Station consisted of an all-in-one computer system running on a Windows 8 interface. The computer station, developed by the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Rehabilitation and Social Integration in Quebec City, was equipped with bio-mechanical and physiological sensors and equipment. The system supports videoconferencing via a connected webcam, providing a medium to deliver the audio-visual communication.

Three studies specified the use of theories and models to inform the design and development [15, 36, 37]. The theories used were as follows: Lafaro et al. (2019) used the Chronic care self-management model (CCM) [38] [37], Huang et al. (2019) is based on Symptom Management theory (SMT) [39] and the e-learning theory [40] [36], and Maguire et al. (2015) used the Medical Research Council (MRC) Complex Interventions Framework [41] [15].

Feasibility and acceptability

Of the eight studies, six were deemed feasible by the study authors [13, 15, 32, 34, 35, 37], with two studies not stating feasibility outcomes [33, 36]. Though, studies that did not explicitly state feasibility outcomes still presented recruitment and retention rates. Huang et al. (2019) reported 91.67% recruitment rate and 100% retention rate. Ji et al., (2019) reported 40.5% recruitment rate and 67.17% retention rate. Three studies did not report the recruitment rates [32, 34, 35]. The mean recruitment rate of the five studies was 62.83 ± 27.99% [13, 15, 33, 36, 37]. Only one study reported a recruitment goal, which was not met [15].

The mean retention rate for the eight studies was 84.77% (67–100%). In two studies, the loss to follow-up was due to the death of participants during the studies [15, 32]. Several concerns pertaining to recruitment were noted, such as little or lack of familiarity with digital technology and the internet, emotional burden, poor health status, lack of interest, knee replacement, scheduled surgery, and patients felt adequately supported by their clinical team and required no further supportive care [13, 15, 34, 37]. Reasons noted for dropout were emotional burden, complications following surgery, cancellation of surgery, and hospital transfer [13, 34, 37]. Of the eight studies, none reported cost or financial cost of the study. Majority of the studies require health care professionals, researchers, and equipment, yet the monetary costs were not discussed. One study highlighted the absence of costing the intervention as a limitation [13]. Detailed information on feasibility results can be found in Table 3.

Due to the varying study designs, adherence was assessed in only three studies [32, 35, 37]. Adherence rates and compliance rates were used as the two primary methods of assessing adherence within the given studies. The mean “adherence rate” was 84.5% (73.5–100%) in the three studies. Adherence rates were defined by the completion of forms [32], completion of exercise sessions [35], and mean sum of pedometer use preoperative and post-discharge [37]. Lafaro et al. (2019) presented adherence rate for both lung and gastrointestinal cancer combined, not as independent outcomes.

Five studies reported one or more measures of satisfaction, with majority of participants reporting they were highly satisfied with the interventions [13, 33,34,35, 37]. Three studies did not report measures of satisfaction [15, 32, 36]. One study reported that majority of participants felt reassured and the advice from the intervention was user friendly and easy to understand [15]. Of those which reported measures of satisfaction, two studies reported reasons for dissatisfaction. Reasons reported in one study were lack of interaction with health care professional, insufficient tailoring of exercises, inadequate insight into progression, and difficulty accessing via mobile phone [13]. The second reported dissatisfaction was due the occurrence of system errors and difficulty in handling the application [34]. No study reported any adverse effects throughout the study duration. Detailed information of the acceptability results can be found in Table 4.

Efficacy

Efficacy outcomes are only reported for RCTs. Of the eight studies, there were two RCTs [33, 36]. Outcomes assessed included QoL, physical functioning [33], and symptom distress [36].

Quality of life

Participants who participated in an online-based health education program had a significant increase in global QoL in comparison to a control group [36]. All participants who participated in a mobile-based pulmonary rehabilitation platform exhibited an overall significant increase in QoL (visit one, 76.05 ± 12.37; visit three, 82.09 ± 13.67 (P = 0.002)), assessed using a visual scale (EuroQol-visual analog scale). However, a small, non-significant change in QoL was observed (visit one, 7.535 ± 1.817; visit three, 6.930 ± 2.849 (P = 0.17)) via the EQ-5D questionnaire (EuroQol 5 dimensions questionnaire) [33]. There was not a significant difference pre-intervention and post-intervention for QoL between the Fixed-interactive exercise group and Fixed exercise group for both visual scale (P = 0.99) or EQ-5D (P = 0.50) [33].

Emotional functioning

Participants who engaged in the online health education program reported significant improvements in emotional function in comparison to those who did not [36]. In fact, those who did not engage with the online health education program displayed a non-significant decrease in emotional function [36]. Significance was determined from baseline (T0) to three months after the program (T3) for both experimental and control groups via the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30).

Physical functioning

Participants who performed physical activity displayed an improvement in their physical function, assessed via their six minute walk distance (6MWD) over a 12-week period (visit one, 433.429 ± 65.595; visit three 471.250 ± 75.691 (P = 0.001)). However, no statistical significant difference (P = 0.30) was reported between the fixed exercise group (58.095 ± 73.663) and fixed-interactive exercise group (25.368 ± 66.640) [33].

Symptom distress

Participants who participated in an online education program had a significant reduction (P < 0.05) in the top ten significant symptom distresses from baseline (1.45 ± 0.08) to three months post program (1.26 ± 0.06), whereas the control group demonstrated a non-significant increase (P = 0.530) from baseline (1.41 ± 0.09) to post three months (1.73 ± 0.27) [36]. Data on symptom distress was collected via the symptom distress scale.

Discussion

This review aimed to examine the evidence of the feasibility, acceptability, and potential efficacy of online supportive care interventions for those LWBLC. The results show that online delivery of supportive care for people LWBLC is feasible and acceptable. However, the field of delivering supportive care in this population is in its infancy. To our knowledge, this systematic review is the first to explore feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of online supportive care for people LWBLC.

Eight studies met the inclusion criteria, two of which were RCTs. The average recruitment rate was 62.58%, though this was not universally reported, and the average retention rate was 84.77%. Problems with recruitment and attrition are common among studies involving people living with and beyond cancer, especially people LWBLC [8]. The challenge recruiting people LWBLC stems from the high symptom burden and lower health performance status [8, 42]. Low rates of participation and consent are common among people living with and beyond cancer, people with advanced diseases, and those approaching palliative end of life care [43, 44]. Older adults (≥ 65y) are reported to be underrepresented in research, with a small increase of older adults in oncological clinical trials over the recent years [45]. Though, people LWBLC typically tend to be older individuals, with 44% of new diagnosis of lung cancer in the UK among those 75 years or older [46], yet the mean age for the included studies was 61 years. This affirms the aforementioned argument by Hurria et al. (2014) that older individuals are underrepresented in oncological research, suggesting that consideration should be given when interpreting the results for this population. The capabilities of older adults to use digital technology is often questioned within literature [34], although elderly adults are becoming increasingly literate using digital technology and eager to adopt new technologies [47].

Adding to the growing body of literature exploring the use of online supportive care for people living with and beyond cancer, this review shows emerging evidence that online supportive care platforms are also feasible and acceptable for people LWBLC. This aligns with the larger body of literature among breast [48, 49], prostate [16, 50], colorectal cancer [51, 52], and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [53, 54], a progressive chronic lung disease which has similar symptoms and QoL impact to lung cancer [55]. This evidence suggests that online supportive care is feasible and acceptable in these populations.

Engaging in supportive cancer care is important for management of symptoms and improvements in quality of life for people LWBLC [8]. In the current global Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic, people living with and beyond cancer are at greater risk of experiencing serious illness if tested positive for the COVID-19 pandemic [56], particularly those receiving chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy for lung cancer [57]. Throughout the pandemic, the frequency of in-person assessments and programs have been severely reduced, leading to a variety of concerns such as, missed diagnosis, unnoticed development of new symptoms, unobserved disease progression, reduction in physical activity sessions, and access to educational resources. Literature has reported weekly symptom monitoring via a web-based patient-reported outcomes platform that was associated with increase survival for those living with and beyond metastatic cancer compared to standard care [58] and those LWBLC in comparison to standard imaging surveillance [59]. Therefore, the importance of delivering supportive care via online modalities is paramount. However, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, barriers existed supporting the implementation of any supportive care for people LWBLC. Economically, there is a considerable financial burden associated with lung cancer, both societal and personal [60]. The cost of travel is an out-of-pocket expensive which could be a barrier for people living with and beyond cancer to access appointments and treatments [60]. In addition, various studies have associated lower socioeconomic status (SES) with higher incidence of lung cancer [61, 62]. The use of digital technology and telehealth has become more prevalent since the COVID-19 pandemic [63], with an exponential growth in platforms such as videoconferencing [57], although the evidence pertaining to online supportive care for people LWBLC is still limited. The evidence that lung cancer is overshadowed in the literature by other forms of cancer is clear within both supportive care in both standard and online modalities [64, 65]. With the complexity of the current global climate, many individuals are unable to seek the supportive care usually provided. This systematic review provided a timely contribution to the sparse knowledge of online supportive care for people LWBLC.

To advance this area, more rigorous research must be conducted, building upon the available pilot-based studies, such as ensuring adequately powered samples and generalisability of results [66]. The studies conducted have shown to have a lower mean age than that of the average for a lung cancer diagnosis. Furthermore, RCTs using a clear randomisation process should be performed to explore the effects online supportive care can present in comparison to well-balance groups [67]. Conducting trials over multiple sites may prove useful regarding greater samples for recruitment. Furthermore, literature suggests that methodological appraisal is often misapplied when assessing non-randomised studies [26]. Studies must appropriately appraise methodological quality of their literature to provide high quality evidence.

Conclusion

Online supportive care for people living with and beyond cancer has shown promise within this review. Given the complexity of delivering cancer services online, the current global COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for online supportive care for people living with and beyond cancer, specifically lung cancer [57]. The studies discussed in this review cover two primary domains of supportive care, symptom management, and increasing QoL, which have been highlighted as key components of supportive care [8]. This illustrates that key components of supportive care can be administered online, showing feasibility and acceptability. Though, the concept of adherence rates requires further exploration within this population. A recent shift has been observed from inpatient to ambulatory care for people living with and beyond cancer and an increased number of outpatients receiving treatment has rapidly increased [15] leading to more individuals being responsible for self-management of treatment-related toxicities within their own home. The use of digital technology such as mobile or web-based platforms to enable real-time communications could be vital in supportive care.

This review provides evidence that online supportive care programs for people LWBLC are feasible and acceptable. The conclusions are limited to a small number of studies, though the strong methodological quality of the studies provide strength in the results. With limited evidence presented from RCTs, it is difficult to determine efficacy. Though online supportive care within lung cancer is in its infancy, further larger RCTS and rigorous studies are warranted.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Carnio S, Di Stefano RF, Novello S (2016) Fatigue in lung cancer patients: symptom burden and management of challenges. Lung Cancer (Auckland, NZ) 7:73–82. https://doi.org/10.2147/LCTT.S85334

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Lung cancer: diagnosis and management 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng122/chapter/Context. Accessed July 11, 2020.

Hesse BW, Greenberg AJ, Rutten LJ (2016) The role of Internet resources in clinical oncology: promises and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 13(12):767–776. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.78

Cancer Research UK. Lung cancer survival statistics. 2014. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/lung-cancer/survival#heading-Two. Accessed July 11, 2020.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer. NICE.org: NICE; 2004.

Findley PA, Sambamoorthi U (2009) Preventive health services and lifestyle practices in cancer survivors: a population health investigation. J Cancer Surviv 3(1):43–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-008-0074-x

Sirois FM, Gick ML (2002) An investigation of the health beliefs and motivations of complementary medicine clients. Soc Sci Med 55(6):1025–1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00229-5

Molassiotis A, Uyterlinde W, Hollen PJ, Sarna L, Palmer P, Krishnasamy M (2015) Supportive care in lung cancer: milestones over the past 40 years. J Thorac Oncol 10(1):10–18. https://doi.org/10.1097/jto.0000000000000407

Li J, Girgis A (2006) Supportive care needs: are patients with lung cancer a neglected population? Psychooncology 15(6):509–516. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.983

Carey M, Lambert S, Smits R, Paul C, Sanson-Fisher R, Clinton-McHarg T (2012) The unfulfilled promise: a systematic review of interventions to reduce the unmet supportive care needs of cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 20(2):207–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1327-1

Dale MJ, Johnston B (2011) An Exploration of the concerns of patients with inoperable lung cancer. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 17(6):285–90. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2011.17.6.285

Maguire R, Papadopoulou C, Kotronoulas G, Simpson MF, McPhelim J, Irvine L (2013) A systematic review of supportive care needs of people living with lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 17(4):449–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2012.10.013

Timmerman JG, Dekker-van Weering MGH, Stuiver MM, Groen WG, Wouters M, Tönis TM et al (2017) Ambulant monitoring and web-accessible home-based exercise program during outpatient follow-up for resected lung cancer survivors: actual use and feasibility in clinical practice. J Cancer Surviv 11(6):720–731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0611-6

Gustafson DH, DuBenske LL, Namkoong K, Hawkins R, Chih MY, Atwood AK et al (2013) An eHealth system supporting palliative care for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. Cancer 119(9):1744–1751. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27939

Maguire R, Ream E, Richardson A, Connaghan J, Johnston B, Kotronoulas G et al (2015) Development of a novel remote patient monitoring system: the advanced symptom management system for radiotherapy to improve the symptom experience of patients with lung cancer receiving radiotherapy. Cancer Nurs 38(2):E37-47. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000150

Forbes CC, Finlay A, McIntosh M, Siddiquee S, Short CE (2019) A systematic review of the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of online supportive care interventions targeting men with a history of prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv 13(1):75–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0729-1

McAlpine H, Joubert L, Martin-Sanchez F, Merolli M, Drummond KJ (2015) A systematic review of types and efficacy of online interventions for cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns 98(3):283–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.002

Ventura F, Ohlén J, Koinberg I (2013) An integrative review of supportive e-health programs in cancer care. Eur J Oncol Nurs 17(4):498–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2012.10.007

Hong YA, Hossain MM, Chou W-YS (2020) Digital interventions to facilitate patient-provider communication in cancer care: a systematic review. Psychooncology 29(4):591–603. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5310

Sugimura H, Yang P (2006) Long-term survivorship in lung cancer: a review. Chest 129(4):1088–1097. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.129.4.1088

Yang P, Cheville AL, Wampfler JA, Garces YI, Jatoi A, Clark MM et al (2012) Quality of life and symptom burden among long-term lung cancer survivors. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer 7(1):64–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182397b3e

Fitch MI (2008) Supportive care framework. Can Oncol Nurs J 18(1):6–24. https://doi.org/10.5737/1181912x181614

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). What study designs can be considered for inclusion in an EPOC review and what should they be called? EPOC resources for review authors, 2013. epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-resources-review-authors (accessed 10 December 2019): Cochrane; 2013.

Kmet L (2004) Lee Robery, Cook L. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields. https://doi.org/10.7939/R37M04F16

Quigley JM, Thompson JC, Halfpenny NJ, Scott DA (2019) Critical appraisal of nonrandomized studies—a review of recommended and commonly used tools. J Eval Clin Pract 25(1):44–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12889

Farrah K, Young K, Tunis MC, Zhao L (2019) Risk of bias tools in systematic reviews of health interventions: an analysis of PROSPERO-registered protocols. Systems Control Found Appl 8(1):280. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1172-8

Lee L, Packer TL, Tang SH, Girdler S (2008) Self-management education programs for age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review. Australas J Ageing 27(4):170–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2008.00298.x

Sotirova MB, McCaughan EM, Ramsey L, Flannagan C, Kerr DP, O’Connor SR et al (2020) Acceptability of online exercise-based interventions after breast cancer surgery: systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Cancer Surviv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00931-6

Lohr KN, Carey TS (1999) Assessing “best evidence”: issues in grading the quality of studies for systematic reviews. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 25(9):470–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30461-8

Maharaj S, Harding R (2016) The needs, models of care, interventions and outcomes of palliative care in the Caribbean: a systematic review of the evidence. BMC Palliat Care 15(1):9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0079-6

Denis F, Viger L, Charron A, Voog E, Dupuis O, Pointreau Y et al (2014) Detection of lung cancer relapse using self-reported symptoms transmitted via an Internet Web-application: pilot study of the sentinel follow-up. Support Care Cancer 22(6):1467–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-2111-1

Ji W, Kwon H, Lee S, Kim S, Hong JS, Park YR et al (2019) Mobile health management platform–based pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with non–small cell lung cancer: prospective clinical trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 7(6):e12645. https://doi.org/10.2196/12645

Park S, Kim JY, Lee JC, Kim HR, Song S, Kwon H et al (2019) Mobile phone app–based pulmonary rehabilitation for chemotherapy-treated patients with advanced lung cancer: pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 7(2):e11094. https://doi.org/10.2196/11094

Coats V, Moffet H, Vincent C, Simard S, Tremblay L, Maltais F et al (2019) Feasibility of an eight-week telerehabilitation intervention for patients with unresectable thoracic neoplasia receiving chemotherapy: a pilot study. Canadian Journal of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine 4(1):14–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/24745332.2019.1575703

Huang C-C, Kuo H-P, Lin Y-E, Chen S-C (2019) Effects of a web-based health education program on quality of life and symptom distress of initially diagnosed advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Educ 34(1):41–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-017-1263-y

Lafaro KJ, Raz DJ, Kim JY, Hite S, Ruel N, Varatkar G et al (2019) Pilot study of a telehealth perioperative physical activity intervention for older adults with cancer and their caregivers. Support Care Cancer 28(8):3867–3876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05230-0

McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, Schulman-Green D, Schilling LS, Lorig K et al (2011) Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin 61(1):50–62. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20093

UCSF School of Nursing Symptom Management Faculty Group. A model for symptom management. The University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing Symptom Management Faculty Group. Image J Nurs Sch. 1994;26(4):272–6.

Moreno R, Mayer RE (1999) Cognitive principles of multimedia learning: the role of modality and contiguity. American Psychological Association, US, pp 358–368

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M (2008) Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 337:a1655. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

Schofield P, Ugalde A, Carey M, Mileshkin L, Duffy M, Ball D et al (2008) Lung cancer: challenges and solutions for supportive care intervention research. Palliat Support Care 6(3):281–287. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1478951508000424

Cooley ME, Sarna L, Brown JK, Williams RD, Chernecky C, Padilla G et al (2003) Challenges of recruitment and retention in multisite clinical research. Cancer Nurs 26(5):376–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002820-200310000-00006 (quiz 85-6)

Sherman DW, McSherry CB, Parkas V, Ye XY, Calabrese M, Gatto M (2005) Recruitment and retention in a longitudinal palliative care study. Appl Nurs Res 18(3):167–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2005.04.003

Hurria A, Dale W, Mooney M, Rowland JH, Ballman KV, Cohen HJ et al (2014) Designing therapeutic clinical trials for older and frail adults with cancer: U13 Conference Recommendations. J Clin Oncol 32(24):2587–2594. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.55.0418

Cancer Research UK. Lung cancer statistics. n.d. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/lung-cancer#heading-Zero. Accessed July 9, 2020.

Vaportzis E, Clausen MG, Gow AJ. Older adults perceptions of technology and barriers to interacting with tablet computers: a focus group study. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1687-. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01687.

Triberti S, Savioni L, Sebri V, Pravettoni G (2019) eHealth for improving quality of life in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 74:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.01.003

Zhu J, Ebert L, Liu X, Wei D, Chan SW-C (2018) Mobile breast cancer e-support program for Chinese women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy (part 2): multicenter randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 6(4):e104. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.9438

Berry Donna L, Hong F, Blonquist Traci M, Halpenny B, Filson Christopher P, Master Viraj A et al (2018) Decision support with the personal patient profile-prostate: a multicenter randomized trial. J Urol 199(1):89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2017.07.076

Cheong IY, An SY, Cha WC, Rha MY, Kim ST, Chang DK et al (2018) Efficacy of mobile health care application and wearable device in improvement of physical performance in colorectal cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Clin Colorectal Cancer 17(2):e353–e362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcc.2018.02.002

Kim B-Y, Park K-J, Ryoo S-B (2018) Effects of a mobile educational program for colorectal cancer patients undergoing the enhanced recovery after surgery. Open Nurs J 12:142–154. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874434601812010142

Hallensleben C, van Luenen S, Rolink E, Ossebaard HC, Chavannes NH (2019) eHealth for people with COPD in the Netherlands: a scoping review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 14:1681–1690. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S207187

North M, Bourne S, Green B, Chauhan AJ, Brown T, Winter J et al (2020) A randomised controlled feasibility trial of E-health application supported care vs usual care after exacerbation of COPD: the RESCUE trial. NPJ Digit Med 3(1):145. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-00347-7

Durham AL, Adcock IM (2015) The relationship between COPD and lung cancer. Lung Cancer 90(2):121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.08.017

Hanna TP, Evans GA, Booth CM (2020) Cancer, COVID-19 and the precautionary principle: prioritizing treatment during a global pandemic. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 17(5):268–270. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-0362-6

Morrison KS, Paterson C, Toohey K (2020) The feasibility of exercise interventions delivered via telehealth for people affected by cancer: a rapid review of the literature. Semin Oncol Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2020.151092

Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, Scher HI, Kris MG, Hudis C et al (2017) Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 318(2):197–198. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7156

Denis F, Basch E, Septans A-L, Bennouna J, Urban T, Dueck AC et al (2019) Two-year survival comparing web-based symptom monitoring vs routine surveillance following treatment for lung cancer. JAMA 321(3):306–307. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.18085

Wood R, Taylor-Stokes G (2019) Cost burden associated with advanced non-small cell lung cancer in Europe and influence of disease stage. BMC Cancer 19(1):214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5428-4

Hovanec J, Siemiatycki J, Conway DI, Olsson A, Stücker I, Guida F et al (2018) Lung cancer and socioeconomic status in a pooled analysis of case-control studies. PLoS ONE 13(2):e0192999. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192999

Van der Heyden JH, Schaap MM, Kunst AE, Esnaola S, Borrell C, Cox B et al (2009) Socioeconomic inequalities in lung cancer mortality in 16 European populations. Lung Cancer 63(3):322–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.06.006

Royce TJ, Sanoff HK, Rewari A (2020) Telemedicine for cancer care in the time of COVID-19. JAMA Oncol 6(11):1698–1699. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2684

Haberlin C, O’Dwyer T, Mockler D, Moran J, O’Donnell DM, Broderick J (2018) The use of eHealth to promote physical activity in cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 26(10):3323–3336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4305-z

Larson JL, Rosen AB, Wilson FA (2019) The effect of telehealth interventions on quality of life of cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Informatics J 26(2):1060–1078. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458219863604

Flickinger M, Tuschke A, Gruber-Muecke T, Fiedler M (2013) In search of rigor, relevance, and legitimacy: what drives the impact of publications? J Bus Econ 84(1):99–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-013-0692-2

Marquart F. Methodological Rigor in Quantitative Research. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. 2017. p. 1–9.

Funding

This study was funded by Yorkshire Cancer Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JC, MPe, SG, and CF created the concept and design of the study. JC, SG, CF created search strategies, and JC performed searches. JC, CF, and MPa screened records, and extracted data. JC and CF analysed and interpreted the data. JC and CF prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research did not involve any studies with human participants or biological material performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

This work was supported by Yorkshire Cancer Research (Grant number HEND405CF).

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Curry, J., Patterson, M., Greenley, S. et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of online supportive care for individuals living with and beyond lung cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 29, 6995–7011 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06274-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06274-x