Abstract

Purpose

Illness uncertainty pervades individuals’ experiences of cancer across the illness trajectory and is associated with poor psychological adjustment. This review systematically examined the characteristics and outcomes of interventions promoting illness uncertainty management among cancer patients and/or their family caregivers.

Methods

PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were systematically searched for relevant literature. We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental studies focusing on interventions for uncertainty management in cancer patients and/or their family caregivers.

Results

Our database searches yielded 26 studies. Twenty interventions were only offered to cancer patients, who were mostly elder, female, and White. All interventions included informational support. Other intervention components included emotional support, appraisal support, and instrumental support. Most interventions were delivered in person and via telephone (n = 8) or exclusively in person (n = 7). Overall, 18 studies identified positive intervention effects on illness uncertainty outcomes.

Conclusion

This systematic review foregrounds the promising potential of several interventions—and especially multi-component interventions—to promote uncertainty management among cancer patients and their family caregivers. To further improve these interventions’ effectiveness and expand their potential impact, future uncertainty management interventions should be tested among more diverse populations using rigorous methodologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Illness uncertainty is defined as “the inability of a person to determine the meaning of illness-related events” [1]. It can persist across the cancer trajectory from the time of diagnosis, through treatment, to long-term survivorship [2] and can be exacerbated by disease progression [3]. Illness uncertainty is widely recognized as a common and significant source of psychosocial stress among cancer patients [4], and studies have shown that increased uncertainty adversely affects cancer patients’ psychological adjustment [5, 6], health behaviors [7], and quality of life [8, 9]. This uncertainty can also extend to cancer patients’ family caregivers. In fact, patients’ partners have often reported higher levels of uncertainty compared to patients [3]. Research has also shown that increases in family caregivers’ illness uncertainty are associated with poorer psychological adjustment to the diagnoses and progression of cancer in patients [10, 11]. For example, uncertainty about the unknown outcomes of childhood cancers (e.g., late effects of cancer treatment, relapse) can increase parents’ distress and dysfunctional behaviors [10].

To address the negative impacts of illness uncertainty on the health outcomes (e.g., quality of life) [12], researchers and practitioners have developed and implemented various interventions to help cancer patients and their family caregivers manage illness uncertainty. Three previous literature reviews have synthesized research developments related to uncertainty management interventions. In their review of interventions for managing uncertainty and fear of recurrence in female breast cancer survivors [13], Dawson and colleagues reported that the main intervention components included mindfulness, more effective patient–provider communication, and stress management through counseling [13]. In their integrative literature review of uncertainty among children with chronic illnesses and their families, Gunter and Duke concluded that the education and psychosocial support is important in reducing uncertainty [14]. In their recent meta-analysis of psychosocial uncertainty management interventions among adult patients with various diagnoses (e.g., cancer, HIV, heart disease) and their family caregivers [15], Zhang et al. reported that psychosocial interventions are effective in reducing short- and long-term uncertainty both among patients and their family caregivers [15].

The existing reviews have focused on patients with various types of chronic illnesses who may face different challenges from patients with cancer [16] or patients with a gender-specific type of cancer (e.g., breast cancer). It therefore remains unclear whether the findings of these reviews are generalizable to patients with other types of cancer. Additionally, although research has shown that children and adolescents with cancer are affected by illness uncertainty [17, 18], no systematic review has examined their experiences of uncertainty management interventions. Researchers and practitioners stand to benefit from a comprehensive review of the literature about illness uncertainty interventions for patients with different types of cancer across age groups and their family caregivers. To this end, our study (a) systematically reviews and synthesizes results of uncertainty management interventions for cancer patients and their family caregivers, (b) identifies the strengths and gaps in this line of research, and (c) suggests directions for future research. Specifically, our systematic review examines the characteristics of participants in studies of illness uncertainty management interventions as well as the characteristics and outcomes of those interventions.

Methods

We adapted a comprehensive systematic review protocol based on the Cochrane Collaboration and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [19]. This protocol was registered with PROSPERO, an international prospective register of systematic reviews, prior to the beginning of the study (registration number CRD42019128004).

Eligibility criteria

We used the population, interventions, comparator, outcomes, and study (PICOS) design(s) to guide our inclusion criteria [20]. Studies eligible for inclusion are as follows: (a) targeted cancer patients and/or their family caregivers; (b) included uncertainty management in their research aims and/or as a part of the intervention’s contents; (c) reported intervention effects on illness uncertainty; (d) used randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-experimental designs; and (e) were published in English between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2019. The search was not limited to studies using a control or comparison group.

Search methods

A university health sciences librarian helped to develop the search terms and identify relevant search databases. We conducted electronic literature searches using six databases: PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The database searches used Boolean terms “OR” and “AND” with combinations of the following search terms: (uncertainty) AND (cancer OR neoplasm*OR tumor OR myeloma OR oncolog*) AND (intervention OR program OR effect OR effectiveness OR treatment OR therapy) AND (patient OR patients OR caregiv* OR family OR families) AND (psych* OR mental* OR emotion*).

To identify studies potentially overlooked by our electronic searches, our research team conducted forward and backward citation chaining and hand searched Web of Science, Google Scholar, and prominent journals in the field to identify relevant articles for inclusion. Two coauthors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts and then—if an article merited further consideration—its full text using Covidence. Covidence is a web-based software platform designed to support the efficient production of systematic reviews [21]. We resolved any discrepancies in the two coauthors’ respective decisions regarding articles’ inclusion via group discussion among all team members.

Assessment of risk of bias in the included studies

We used the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias Tool [22] to assess various sources of bias: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other possible sources of bias (Appendix). Each domain was endorsed with a rating of “low risk,” “high risk,” or “unclear risk” following guideline’s criteria. Two coauthors independently conducted all risk of bias assessments, and we resolved any differences in their assessments through team discussion.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two of the coauthors independently extracted relevant data from the studies that met our inclusion criteria. We compared these extracted results and resolved any discrepancies through team discussion before merging the data. Because the included studies displayed different participant characteristics, intervention components, outcomes, and follow-up periods, we could not conduct a meta-analysis of their findings. We summarized the narratives and themes of each study and its results. Guided by House’s conceptualization of social support [23], we classified each intervention’s components into four categories: informational support, emotional support, appraisal support, and instrumental support.

Results

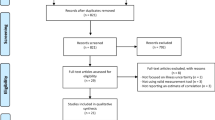

As shown in Fig. 1, our initial search of electronic databases and records and our hand searches of other sources yielded 1156 records. After removing duplicates, we identified 681 articles for title and abstract review, of which 49 were retained for a full-text review. After removing the studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria, we included 26 articles in this review.

Characteristics of studies

The majority of studies were conducted in the USA (n = 16). Others were conducted in Canada, China, Japan, United Kingdom (UK), and Vietnam. Eighteen studies were RCTs; one study used a RCT crossover design [24]. Eight studies were quasi-experimental studies (i.e., five “1-group pretest-posttest” studies, two “2-group pretest-posttest” studies, and one “2-group posttest” study) (Table 1). Among the 20 studies that included a control group, 12 studies used usual care, and eight included an active control group (e.g., a self-help group [25]; groups receiving recorded and written messages [26], telephone calls [27], and delayed interventions [28]). Sample sizes of included studies ranged from 9 [29] to 968 participants [30]. Among all studies, only seven studies were guided by theoretical frameworks such as the stress and coping theory (n = 5) [30,31,32,33,34], the uncertainty in illness theory (n = 1) [29], the double ABCX model (n = 1) [34], and the resilience model (n = 1) [35].

Characteristics of participants

Twenty interventions were only offered to cancer patients. Two studies targeted family caregivers (i.e., the parents of children with cancer) [34, 36]. Four interventions were offered to both cancer patients and their partners and/or family caregivers [30,31,32,33].

Participants were recruited from hospitals, by invitation from a care provider, or via mailing and poster initiatives. The majority of studies recruited homogeneous patient populations, including patients with breast cancer (n = 8), prostate cancer (n = 6), brain tumor (n = 2), leukemia (n = 1), gynecological cancer (n = 1), and ovarian cancer (n = 1). Approximately 26.9% of studies (n = 7) targeted patients with various types of cancer. Regarding the stages of the cancer trajectory, these studies focused on cancer patients who were post-treatment (n = 8); patients with newly diagnosed cancer (n = 6); patients with advanced cancer (n = 5); patients undergoing active surveillance for cancer (n = 2); patients receiving treatment (n = 2); patients in recurrence (n = 2); and/or patients at a mix of stages (n = 1). With only two studies targeting parents of children and adolescents with cancer, the majority of the studies have focused on participants who were mostly female and White, and with an average age ranged from 44 to 72 years.

Intervention characteristics

Table 2 summarizes the interventions’ characteristics. Nineteen studies (73.1%) included uncertainty management as their main aim.

Theoretical basis

Twelve studies (46%) described the theoretic frameworks used to guide different interventions. Five interventions were developed based on Mishel’s uncertainty in illness theory [27, 37,38,39,40]. Other theoretical models that guided the development of illness uncertainty management interventions also included the thematic counseling model [25], self-regulation theory [26], Leventhal’s common sense model [37], Brooten’s cost-quality model [41], self and family management framework [42], theory of self-efficacy, theory of stress and coping [31], cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy [43], and mindfulness-based stress reduction [44].

Contents and components

All of the interventions in our sampled studies included informational support that provided knowledge and resources related to illness, treatment, procedures, and symptom management. Eleven studies included emotional and psychological support from interventionist and peer groups. Nine studies included appraisal support that provided information and skills training for self-evaluation and positive perception, such as cognitive reframe and restructuring. Five studies included instrumental support that helped improve participants’ care coordination and ability to manage resources, referrals (social services, mental health, physical therapy), and continual follow-up schedules. Sixteen studies included two or more types of intervention components.

Mode of delivery, format, duration, and dosage

The studied interventions employed a variety of delivery modes. The majority of these interventions used both in-person and telephone delivery (n = 8) or in-person delivery (n = 7). The remaining eleven interventions used other delivery mechanisms including CD [27], DVDs [45, 46], telephone calls [38], informational booklets [42], internet [29], phone apps [36], or a combination of in-person delivery with DVD and CD content [43]. Most interventions were delivered to participants individually (n = 14), in a group format (n = 3) [36, 37, 44], or in family format (n = 4) [30, 32,33,34]. Other interventions used a combination of individual and group (n = 2) [25, 35], individual and family (n = 2) [38, 39], or group and family (n = 1) [31] delivery methods. The duration and dosage of the uncertainty management interventions varied across studies, ranging from one session [46] to 1-year period [35].

Interventionist

In thirteen studies, nurses delivered the interventions. Five interventions were delivered by professionals who had counseling or psychosocial background and training [28, 31, 35, 43, 44]. Five interventions were designed or delivered by multidisciplinary professionals [24, 34, 36, 37, 46]. One intervention was delivered by research staff [42] and one intervention design involved physicians [47]. One study did not report on the professional background of the interventionists [26].

Intervention outcome

Illness uncertainty assessment

The scale most commonly used to measure an intervention’s effect on uncertainty was the Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale (MUIS) (n = 19). This scale has different versions including MUIS-Community version [48], MUIS-Survivor version [27], MUIS-Short version [40], and Parents’ Perception of Uncertainty [36], which is based on the MUIS and measures parents’ uncertainty. Other studies measured uncertainty using the symptom and ambiguity subscale of MUIS [26, 49], the Decisional Conflict Scale-uncertainty subscale [46, 47], Parent Experience of Child Illness-Short Form [34], and the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale [43, 44]. One study measured uncertainty using a 1-item scale [24]. One study measured uncertainty using three proxy measures (i.e., problem-solving, patient–provider communication, and cancer knowledge) [39]. Most studies assessed illness uncertainty outcomes using a longitudinal design with two time points (n = 6); three time points (n = 12); four time points (n = 6); or six time points (n = 1) [41].

Illness uncertainty outcomes

Overall, 65% of studies (n = 17) suggested that an illness uncertainty management intervention had a positive effect on uncertainty outcomes. Out of the eighteen RCTs, eleven studies demonstrated that the participants in the intervention group reported significant less uncertainty than those in the control group at follow-ups. Of these studies, eight studies assessed outcomes at multiple time points. Five studies reported more reduction in uncertainty in the intervention group over time [27, 28, 35, 39, 49]. Among eight quasi-experimental studies, three studies with a control group found that participants in the intervention groups reported significantly less uncertainty compared to those in the control group [36, 40, 45]. Among five quasi-experimental studies without a control group, three studies showed that intervention participants reported a significant decrease in uncertainty over time [34, 37, 46].

Risk of bias assessment

We evaluated each study’s risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias Tool (Table 3). The eighteen RCTs had unclear (n = 11), high (n = 2), or low (n = 5) risk of bias. Most trials were classified as having unclear risk of bias because they did not describe the method used to generate the allocation sequence or report any strategies to maintain intervention fidelity (e.g., consistent intervention use among participants). We found that six quasi-experimental studies had high risk of bias. Most quasi-experimental studies used one-group pre- and post-designs without a control group; therefore, they had high risk of bias in random sequence generation and baseline imbalance.

Discussion

This study systematically reviewed the characteristics and outcomes of illness uncertainty management–related interventions for adult and childhood cancer patients as well as their family caregivers. We found that all interventions evaluated in the included studies provided informational support. Other intervention components included emotional support, appraisal support, and instrumental support. The majority of studies used both in-person and telephone or in-person intervention delivery modes. The majority of studies suggested positive effects of illness uncertainty management–related interventions on uncertainty outcomes. With only two studies focused on parents of children and adolescents with cancer, the majority of interventions were only offered to cancer patients, who were mostly older adults, female, and White.

Overall, the majority of studies (65%) found that illness uncertainty management–related interventions had positive effects on uncertainty outcomes. Multi-component interventions, which used integrated resources to target multiple aspects of illness uncertainty such as informational support and emotional support, appear to be the most effective in managing illness uncertainty in cancer patients and their family caregivers. For example, Lebel et al. found that one intervention proved effective when employing a combination of introductory material about illness, cognitive restructuring and triggers, coping skills (e.g., relaxation, calming self-talk, guided imagery), and practice expressing emotion and confronting specific fears [37]. However, the positive effects of only a few interventions appeared to endure over time, possibly indicating that many interventions’ duration should be extended or include booster sessions as needed [38].

In general, we found that uncertainty management interventions were comprised of a variety of components including informational, emotional, appraisal, and instrumental support. Informational support is the key to helping cancer patients and their family caregivers manage uncertainty. Our findings corroborate those of two previous literature reviews of psychosocial interventions for managing uncertainty in childhood cancer patients and adult patients with different chronic illnesses [14, 15]. Findings from these reviews may also collectively indicate that individualized educational interventions provide information that empowers patients to successfully develop positive coping mechanisms. These findings are consistent with core tenets of Mishel’s uncertainty in illness theory, which posits that uncertainty occurs when patients lack the information or knowledge needed to fully interpret an illness and its treatment [1]. Informational support can enlarge patients’ information and knowledge base, enabling them to better understand an illness and thus experience less uncertainty. Moreover, when uncertainty occurs, it can be difficult for patients to form a cognitive structure [1]. Appraisal supports such as cognitive reframing can help patients reinterpret their illness and view a traumatic event as manageable [38]. Emotional and instrumental support can also provide patients with psychosocial resources to manage their uncertainty.

Most interventions were delivered using either in-person and telephone or in-person formats. This finding contrasts with Zhang et al.’s systematic review and meta-analysis of patients with chronic illnesses, which identified written educational materials as the most frequently used mode of intervention delivery [15]. Given the complexity of information provision and cancer patients’ potential for psychosocial distress, in-person meetings may be the preferred mode of intervention delivery. A format combining in-person and follow-up telephone components can both evaluate patients’ current understandings of their illness and help them reassess their emotional responses [27]. Our systematic review found limited evidence of the effectiveness of technology-based (e.g., web-based, apps) uncertainty management interventions [29, 36]. This area of research is still emerging, as indicated by the recent publication dates of studies of these technology-based interventions, their pilot and feasibility research aims, and their use of small sample sizes. Given these interventions’ potential ability to provide cost-effective psychosocial services [50] to manage uncertainty across the cancer care continuum, researchers should develop and evaluate technology-based interventions for uncertainty management using a rigorous research design (e.g., RCT) with a sufficiently powered sample.

Notably, only four interventions were offered jointly to cancer patients and their spouses or partners, and only one of these reported significant improvement in the uncertainty outcome among cancer patients and their spouses [33]. This comparatively low number perhaps reflects the challenges to conducting family-based research, such as explaining the purpose of the research to multiple participants, having an extended recruitment phase that involves contacting and obtaining consent from more people, and high refusal rates [31, 51]. The small number of interventions that included spouses or partners is striking, as family caregivers play key roles in supporting cancer patients [52] and often experience higher levels of uncertainty than patients [3]. Interventions delivered to patients’ family caregivers can improve their knowledge, coping skills, and quality of life [53], which will in turn improve cancer patients’ care and outcomes (e.g., quality of life) given the synergetic interdependent relationships between cancer patients and their family caregivers [54]. There is a pressing need for future research to inform the development of interventions designed to manage uncertainty for both cancer patients and their caregivers.

Our review also indicates that future research must diversify the age, gender, and racial distributions of sample populations used to evaluate the outcomes of illness uncertainty interventions. Although previous research has shown that uncertainty is a common experience for children and adolescents with cancer [14], we identified only two interventions that assisted the parents of children with cancer to manage uncertainty [34, 36], and no intervention in our sample targeted children and adolescents with cancer. Therefore, because experiences of uncertainty can vary across different age groups or developmental stages [55], researchers should develop age-appropriate interventions that take into account the specific needs of children and adolescents with cancer. Furthermore, most of the participants in the intervention studies in this review were female, White, and older adult cancer patients. Future research regarding illness uncertainty management interventions should create strategies to increase the number of male patients and family caregivers in intervention programming. Although recruiting men for clinical trials is difficult because men are often reluctant to access services and to recognize that they need help [31], male cancer patients (e.g., prostate cancer) often experience uncertainty about their treatment decision-making and/or their management of cancer treatment-related symptoms and side effects [3, 56]. Finally, although two interventions succeed to include a sufficient number of African American cancer patients [27, 38], the majority of the study populations were White. Given that one study found that African American cancer patients reported higher levels of uncertainty than White cancer patients [3], future intervention should be tailored to help patients from minority groups and researchers should gather data about the effects of interventions using more diverse samples of cancer patients and their family caregivers.

According to the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias Tool, most studies had “unclear” or “high risk” of bias due to their unclear reporting. Many studies have unclear reporting of the study procedures that do not meet reporting standards. Future studies should provide complete, clear, and transparent information about how to create and present a research methodology and findings in accordance with CONSORT criteria and flowchart templates.

Limitations

This review’s findings should be considered in light of several limitations. The studies we sampled differed considerably in their study participants’ demographic variables (e.g., older, female, and White cancer patients), types of interventions, outcome measures, and timing of follow-ups. We could not conduct a meta-analysis that synthesizes their discrepant findings, which would have provided more rigorous evidence of the effects of uncertainty management interventions for cancer patients and their family caregivers. Additionally, our review only focused on interventions’ effects on uncertainty outcomes. Future research should examine the effects of uncertainty management interventions on other outcomes in order to get a more comprehensive picture of the effect of interventions. We also focused only on peer-reviewed published studies and may have missed relevant studies from the gray literature. Excluding unpublished studies likely increases the potential for biased findings; however, we included studies that reported non-significant results, thus mitigating the possibility of publication selection bias.

Clinical and research implications

Our review has numerous implications for future clinical practice and research. Providing uncertainty management interventions with multiple components at different phases of the cancer trajectory may significantly reduce uncertainty and facilitate adaptation among patients and family caregivers. There is strong evidentiary support that multi-component interventions yield effective outcomes. However, more research is needed to compare the discrete effects of different intervention components, modes of delivery, and formats on uncertainty management outcomes among cancer patients and their family caregivers. This research should also include study populations with diverse backgrounds (e.g., by age, gender, and/or race), and in particular seek to engage children and adolescents with cancer, males, and African Americans—all groups for whom few if any tailored uncertainty management interventions currently exist.

Conclusion

This systematic review underlines the promising potential of uncertainty management interventions—especially interventions involving multiple components including informational, emotional, appraisal, and instrumental support—to help cancer patients and their family caregivers manage illness uncertainty. Future research needs to employ a rigorous research methodology in order to test uncertainty management interventions among a diverse population and to ensure complete and accurate reporting of the research procedures and findings.

Data availability

All studies included in this review are publicly available.

References

Mishel MH (1988) Uncertainty in illness. J Nurs Scholarsh 20(4):225–232

Garofalo JP, Choppala S, Hamann HA, Gjerde J (2009) Uncertainty during the transition from cancer patient to survivor. Cancer Nurs 32(4):E8–E14

Guan T, Guo, PR, Santacroce, SJ, Chen, DG, Song L (2020) A longitudinal perspective on illness uncertainty and its antecedents for patients with prostate cancer and their partners. Oncol Nurs Forum 47(6):721–731

Jabloo VG et al (2017) Antecedents and outcomes of uncertainty in older adults with cancer: a scoping review of the literature. Oncol Nurs Forum 44(4):E152–E167

Eisenberg SA, Kurita K, Taylor-Ford M, Agus DB, Gross ME, Meyerowitz BE (2015) Intolerance of uncertainty, cognitive complaints, and cancer-related distress in prostate cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 24(2):228–235

Germino BB, Mishel MH, Belyea M, Harris L, Ware A, Mohler J (1998) Uncertainty in prostate cancer: ethnic and family patterns. Cancer Pract 6(2):107–113

Santacroce SJ, Lee YL (2006) Uncertainty, posttraumatic stress, and health behavior in young adult childhood cancer survivors. Nurs Res 55(4):259–266

Wonghongkul T, Dechaprom N, Phumivichuvate L, Losawatkul S (2006) Uncertainty appraisal coping and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 29(3):250–257

Sammarco A (2001) Perceived social support, uncertainty, and quality of life of younger breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 24(3):212–219

Haegen MV, Etienne AM (2018) Intolerance of uncertainty in parents of childhood cancer survivors: a clinical profile analysis. J Psychosoc Oncol 36(6):717–733

Tackett AP, Cushing CC, Suorsa KI, Mullins AJ, Gamwell KL, Mayes S, McNall-Knapp R, Chaney JM, Mullins LL (2016) Illness uncertainty, global psychological distress, and posttraumatic stress in pediatric cancer: a preliminary examination using a path analysis approach. J Pediatr Psychol 41(3):309–318

Guan T, Santacroce SJ, Chen DG, Song L (2020) Illness uncertainty, coping, and quality of life among patients with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 29(6):1019–1025

Dawson G, Madsen LT, Dains JE (2016) Interventions to manage uncertainty and fear of recurrence in female breast cancer survivors: a review of the literature. Clin J Oncol Nurs 20(6):E155–E161

Gunter MD, Duke G (2018) Reducing uncertainty in families dealing with childhood cancers: an integrative literature review. Pediatr Nurs 44(1):21–37

Zhang Y, Kwekkeboom K, Kim KS, Loring S, Wieben AM (2020) Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial uncertainty management interventions. Nurs Res 69(1):3–12

Tritter JQ, Calnan M (2002) Cancer as a chronic illness? Reconsidering categorization and exploring experience. Eur J Cancer Care 11(3):161–165

Panjwani AA, Marín-Chollom AM, Pervil IZ, Erblich J, Rubin LR, Schuster MW, Revenson TA (2019) Illness uncertainties tied to developmental tasks among young adult survivors of hematologic cancers. J Adolesc and Young Adult Oncol 8(2):149–156

Fortier MA, Batista ML, Wahi A, Kain A, Strom S, Sender LS (2013) Illness uncertainty and quality of life in children with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 35(5):366–370

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000100

Cochrane Community [Internet]. Author; c2020. About covidence.; 2018 [cited 2020 June 22]. Available from: https://community.cochrane.org/help/tools-and-software/covidence/about-covidence

Higgins JP et al (2011) The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 343:d5928

House JS, Umberson D, Landis KR (1988) Structures and processes of social support. Annu Rev Soc 14(1):293–318

Mori M, Fujimori M, Vliet LM, Yamaguchi T, Shimizu C, Kinoshita T, Morishita-Kawahara M, Inoue A, Inoguchi H, Matsuoka Y, Bruera E, Morita T, Uchitomi Y (2019) Explicit prognostic disclosure to Asian women with breast cancer: a randomized, scripted video-vignette study (J-SUPPORT1601). Cancer. 125(19):3320–3329

Chow KM, Chan CWH, Chan JCY, Choi KKC, Siu KY (2014) A feasibility study of a psychoeducational intervention program for gynecological cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs 18(4):385–392

Christman NJ, Cain LB (2004) The effects of concrete objective information and relaxation on maintaining usual activity during radiation therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 31(2):E39–E45

Germino BB, Mishel MH, Crandell J, Porter L, Blyler D, Jenerette C, Gil KM (2013) Outcomes of an uncertainty management intervention in younger African American and Caucasian breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 40(1):82–92

Tomei C, Lebel S, Maheu C, Lefebvre M, Harris C (2018) Examining the preliminary efficacy of an intervention for fear of cancer recurrence in female cancer survivors: a randomized controlled clinical trial pilot study. Support Care Cancer 26(8):2751–2762

Kazer MW, Bailey DE, Sanda M, Colberg J, Kelly WK (2011) An internet intervention for management of uncertainty during active surveillance for prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 38:561–568

Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, Kalemkerian G, Zalupski M, LoRusso P, Hayes DF, Hussain M, Ruckdeschel J, Fendrick AM, Trask PC, Ronis DL, Kershaw T (2013) Randomized clinical trial of a brief and extensive dyadic intervention for advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psychooncology. 22(3):555–563

McCaughan E, Curran C, Northouse L, Parahoo K (2018) Evaluating a psychosocial intervention for men with prostate cancer and their partners: outcomes and lessons learned from a randomized controlled trial. Appl Nurs Res 40:143–151

Northouse L, Kershaw T, Mood D, Schafenacker A (2005) Effects of a family intervention on the quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psychooncology. 14(6):478–491

Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, Montie JE, Sandler HM, Forman JD, Hussain M, Pienta KJ, Smith DC, Kershaw T (2007) Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer. 110(12):2809–2818

Hendricks-Ferguson VL, Pradhan K, Shih CS, Gauvain KM, Kane JR, Liu J, Haase JE (2017) Pilot evaluation of a palliative and end-of-life communication intervention for parents of children with a brain tumor. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 34(3):203–213

Ye ZJ, Liang MZ, Qiu HZ, Liu ML, Hu GY, Zhu YF, Zeng Z, Zhao JJ, Quan XM (2016) Effect of a multidiscipline mentor-based program, Be Resilient to Breast Cancer (BRBC), on female breast cancer survivors in mainland China: a randomized, controlled, theoretically-derived intervention trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 158(3):509–522

Wang J, Howell D, Shen N, Geng Z, Wu F, Shen M, Zhang X, Xie A, Wang L, Yuan C (2018) mHealth supportive care intervention for parents of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: quasi-experimental pre- and postdesign study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 6(11):e195

Lebel S, Maheu C, Lefebvre M, Secord S, Courbasson C, Singh M, Jolicoeur L, Benea A, Harris C, Fung MFK, Rosberger Z, Catton P (2014) Addressing fear of cancer recurrence among women with cancer: a feasibility and preliminary outcome study. J Cancer Surviv 8(3):485–496

Mishel MH, Belyea M, Germino BB, Stewart JL, Bailey DE, Robertson C, Mohler J (2002) Helping patients with localized prostate carcinoma manage uncertainty and treatment side effects: nurse-delivered psychoeducational intervention over the telephone. Cancer. 94(6):1854–1866

Mishel MH, Germino BB, Lin L, Pruthi RS, Wallen EM, Crandell J, Blyler D (2009) Managing uncertainty about treatment decision making in early stage prostate cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Patient Educ Couns 77(3):349–359

Ha XTN, Thanasilp S, Thato R (2019) The effect of uncertainty management program on quality of life among Vietnamese women at 3 weeks postmastectomy. Cancer Nurs 42(4):261–270

Ritz LJ, Nissen MJ, Swenson KK, Farrell JB, Sperduto PW, Sladek ML, Lally RM, Schroeder LM (2000) Effects of advanced nursing care on quality of life and cost outcomes of women diagnosed with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 27(6):923–932

Schulman-Green D, Jeon S (2017) Managing cancer care: a psycho-educational intervention to improve knowledge of care options and breast cancer self-management. Psychooncology. 26(2):173–181

Wells-Di Gregorio SM et al (2019) Pilot randomized controlled trial of a symptom cluster intervention in advanced cancer. Psychooncology. 28(1):76–84

Victorson D, Hankin V, Burns J, Weiland R, Maletich C, Sufrin N, Schuette S, Gutierrez B, Brendler C (2017) Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary psychological benefits of mindfulness meditation training in a sample of men diagnosed with prostate cancer on active surveillance: results from a randomized controlled pilot trial. Psychooncology. 26(8):1155–1163

Dharmarajan KV, Walters CB, Levin TT, Milazzo CA, Monether C, Rawlins-Duell R, Tickoo R, Spratt DE, Lovie S, Giannantoni-Ibelli G, McCormick B (2019) A video decision aid improves informed decision making in patients with advanced cancer considering palliative radiation therapy. J Pain Symptom Manag 58(6):1048–1055

El-Jawahri A et al (2010) Use of video to facilitate end-of-life discussions with patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 28(2):305–310

Liu LN, Li CY, Tang ST, Huang CS, Chiou AF (2006) Role of continuing supportive cares in increasing social support and reducing perceived uncertainty among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer in Taiwan. Cancer Nurs 29(4):273–282

Sussman J, Bainbridge D, Whelan TJ, Brazil K, Parpia S, Wiernikowski J, Schiff S, Rodin G, Sergeant M, Howell D (2018) Evaluation of a specialized oncology nursing supportive care intervention in newly diagnosed breast and colorectal cancer patients following surgery: a cluster randomized trial. Support Care Cancer 26(5):1533–1541

McCorkle R, Dowd M, Ercolano E, Schulman-Green D, Williams AL, Siefert ML, Steiner J, Schwartz P (2009) Effects of a nursing intervention on quality of life outcomes in post-surgical women with gynecological cancers. Psychooncology. 18(1):62–70

Fridriksdottir N, Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, Ingadottir B, Hafsteinsdottir EJG (2018) Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients’ symptoms: review of randomized trials. Support Care Cancer 26(2):337–351

Northouse LL, Rosset T, Phillips L, Mood D, Schafenacker A, Kershaw T (2006) Research with families facing cancer: the challenges of accrual and retention. Res Nurs Health 29(3):199–211

Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, Litzelman K, Chou WYS, Shelburne N, Timura C, O’Mara A, Huss K (2016) Caring for caregivers and patients: research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 122(13):1987–1995

Northouse L, Williams AL, Given B, McCorkle R (2012) Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 30(11):1227–1234

Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, Weiss D (2012) The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Semin Oncol Nurs 28(4):236–245

Stewart JL, Mishel MH, Lynn MR, Terhorst L (2010) Test of a conceptual model of uncertainty in children and adolescents with cancer. Res Nurs Health. 33(3):179–191

Hillen MA, Gutheil CM, Smets EMA, Hansen M, Kungel TM, Strout TD, Han PKJ (2017) The evolution of uncertainty in second opinions about prostate cancer treatment. Health Expect 20(6):1264–1274

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Elizabeth Moreton who helped to develop the search terms and identify search databases. We also would like to thank Dr. Jordan Wingate for his editorial assistance.

Code availability

Not applicable

Funding

Lixin Song’s work was partially supported by R01NR016990 National Institute of Nursing Research (PI: Song), R21 CA212516 National Cancer Institute (PI: Song), and University Cancer Research Fund, UNC-Chapel Hill Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (LCCC). Guan’s and Yousef’s work was partially supported by University Cancer Research Fund, UNC-Chapel Hill LCCC (PI: Song).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guan, T., Qan’ir, Y. & Song, L. Systematic review of illness uncertainty management interventions for cancer patients and their family caregivers. Support Care Cancer 29, 4623–4640 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05931-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05931-x