Abstract

Purpose

This study investigated the feasibility of patient ambassador support in newly diagnosed patients with acute leukemia during treatment.

Methods

A multicenter single-arm feasibility study that included patients newly diagnosed with acute leukemia (n = 36) and patient ambassadors previously treated for acute leukemia (n = 25). Prior to the intervention, all patient ambassadors attended a 6-h group training program. In the intervention, patient ambassadors provided 12 weeks of support for patients within 2 weeks of being diagnosed. Outcome measures included feasibility (primary outcome), safety, anxiety, and depression measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, quality of life by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Leukemia and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire, and symptom burden by MD Anderson Symptom Inventory, the Patient Activation Measure, and the General Self-Efficacy Scale.

Results

Patient ambassador support was feasible and safe in this population. Patients and patient ambassadors reported high satisfaction with the individually adjusted support, and patients improved in psychosocial outcomes over time. Patient ambassadors maintained their psychosocial baseline level, with no adverse events, and used the available support to exchange experiences with other patient ambassadors and to manage challenges.

Conclusion

The patient ambassador support program is feasible and has the potential to be a new model of care incorporated in the hematology clinical care setting, creating an active partnership between patients and former patients. This may strengthen the existing supportive care services for patients with acute leukemia.

Trial registration

NCT03493906

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acute leukemia (AL) is a malignant hematological disease with a rapid onset which, in curative treatment regimens, is followed by intensive high-dose chemotherapy, risk of life-threatening complications, and a significant symptom burden [1,2,3,4,5]. AL is classified into subtypes of acute myeloid or lymphoid leukemia (AML/ALL), each with distinguishing characteristics affecting both prognosis and treatment. A sub-type of AML is acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) accounting for around 5–10% of all AML diagnosis [1]. Through the last decade, curative regimens for AL have only improved to a limited extent [1], while supportive care has improved significantly [6,7,8,9]. Specifically, in Northern Europe and the USA, an increasing number of patients are receiving the majority of their treatment in the outpatient setting [6,7,8,9]. These improvements are crucial but can result in the patients having less contact with health professionals and other patients with AL during treatment.

Being diagnosed with a life-threatening disease like AL, which comprises an unpredictable long-term clinical course, can be a traumatic experience, and many patients report high levels of psychological distress [2, 10,11,12]. In a previous study, we identified that newly diagnosed patients with AL experienced feeling jolted by the diagnosis and uncertainty about the future [13]. Moreover, they considered social support, including support from other patients with AL, as a lifeline because it had the potential to help them actively manage their situation and, more importantly, regain hope [13].

Peer support may benefit not only the person being supported but also the supporter [14, 15]. Peers possess an understanding and a first-hand experience of the disease and its treatment, and may provide support to a peer who is at an earlier stage of treatment or recovery [16]. Social comparison theory may partially explain the beneficial influence of peer support [17]. Comparisons with others in a similar situation to oneself can normalize the experience, provide positive role modeling, reduce the threat, and aid in coping with the new challenges [18]. In peer support programs, the peer supporter may also find comparisons helpful because they put their own disease trajectory and life experiences into perspective [14, 19]. The evidence of the effect of peer support programs in patients with cancer is growing [20, 21]. A review of one-to-one peer support programs in cancer care substantiates the beneficial effect on the psychosocial adjustment and the resulting high participant satisfaction with peer support [21]. Yet, due to the potential vulnerability of peer supporters, it is suggested that future research monitor their psychosocial state and elucidate the potential impact on patients and peer supporters [19, 21].

In one study, it has been shown that patients with AL requested support interventions in which former patients treated for AL support patients newly diagnosed with AL [22]. There is no evidence to date on the feasibility of a one-to-one peer support intervention in patients with AL [20, 21]. The existing research can only be transferred, to a limited extent, to patients with AL. Thus, due to acute onset, the intensity of treatment regimens often complicated by serious infections, and the risk of substantial symptom burden, it is relevant to investigate this type of social support in patients with AL. In the present study, a peer supporter is a former patient previously treated for AL who was named a patient ambassador (PA). This study was conducted to investigate the feasibility of patient ambassador support (PAS) in newly diagnosed patients with AL during initial treatment.

Material and methods

Study design

This multicenter single-arm feasibility study was conducted at three hematology departments in Denmark: Rigshospitalet, Herlev/Gentofte Hospital and Zealand University Hospital, Roskilde. The intervention included a 12-week PAS program for newly diagnosed patients with AL during their initial treatment with high-dose chemotherapy.

Participants and procedures

The study included two categories of participants recruited from all three hematology departments: patients and PAs.

Eligibility criteria:

-

Patients > 18 years and included within the first 2 weeks from time of diagnosis with acute myeloid leukemia or acute lymphatic leukemia if intensive chemotherapy treatment was planned.

-

PAs > 18 years, previously diagnosed and treated for AL with intensive chemotherapy, at least 1 year since diagnosis, and in complete remission.

Participants were excluded if they did not understand, if they did not read and speak Danish, and if they had an unstable medical disease or any cognitive/psychiatric disorders.

Recruitment

PAs were recruited voluntarily from October 2017 to January 2018 using posters and flyers at the hematology departments (n = 4) and the Patient Association of Lymphoma, Leukemia, and Myelodysplastic Syndromes (n = 1), or they were selected and then approached by phone or mail (n = 30) by their primary hematologist in cooperation with the principle investigator (KHN), who screened eligible PAs for their suitability in a telephone interview. The PAs received a monetary incentive of 130 euro to cover transport expenses. The project nurse and primary investigator approached and recruited patients from February 2018 to June 2019 at the inpatient or outpatient clinic. Eligible participants received oral and written information from the principle investigator. Included participants then provided written informed consent prior to inclusion, and the PAs also signed a confidentiality agreement. Exclusion criteria for the participants were relapse (PAs), psychological conditions (delirium or severe depression), hospitalization in intensive care unit for more than 2 weeks, or transition to terminal care.

Intervention

Preparation for the intervention

Prior to the intervention, the PAs attended a specially tailored 6-h program carried out by the principle investigator, the project nurse, and the project psychologist. The program included an introduction to the study, an overview of the disease and treatment regimes, and information and training on psychological issues and communication skills. There were discussions in small groups and in plenum on their personal goals, motivation, and concerns about volunteering. Upon completion of the training program, they received an information dossier with a checklist and guidelines, which included a list of relevant actions for PAs to take, and a tool to document the intervention.

PAS program

PAs provided 12 weeks of support to patients newly diagnosed with AL. Included patients and PAs were matched by the principle investigator immediately upon receipt of their informed content according to sex, age, type of AL, and/or other factors individually expressed prior to the intervention. Patients and ambassadors were matched independent of which of the three hematology departments they were recruited from. The PA initiated contact with the patient within 48 h, either by phone (conversation/text message), e-mail, or a face-to-face meeting, depending on the individual patient’s needs. However, face-to-face meetings were recommended for the purpose of developing a relationship. PAs followed one patient at a time, with a minimum of 4 weeks between patients. The primary investigator followed up on the initial and final contact, and during the intervention, if necessary.

Support and safety

During the intervention, the PAs were offered network meetings with supervision every 6 weeks with the principle investigator and the psychologist. If requested, the psychologist also provided individual supervision during the intervention.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

Feasibility studies focus on the process of developing and implementing the intervention, and eight areas of focus are described as feasibility criteria [23]. We adopted the following criteria in this study: acceptability, practicability, and safety and support [23, 24]. Evaluations were also obtained from patients and PAs. Finally, the PAs kept a record of the frequency, type, and topics of their communication. Participant and disease characteristics were obtained from the patient and PA, and from medical records.

Secondary outcome

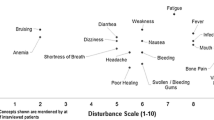

Participants filled out electronic or paper versions of patient-reported outcome questionnaires at baseline and at the 12- and 24-week follow-up. Psychological well-being was assessed and measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [25], while quality of life (QOL) was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Leukemia (FACT-LEU) [26] and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) [27]. Symptom burden was assessed using the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDSAI) [28], while the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) [29, 30] was used to gauge the patients’ understanding of their own health and health care, and coping appraisal was assessed with the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) [31].

Statistical analysis

REDCap was used to collect and manage survey data and as an online record to register all contacts from participants with primary investigator, project nurses, and the psychologist [32, 33]. A sample size of 30 is recommended for feasibility trials. Due to the prognosis and significant symptom burden in patients with AL, they have a risk of high attrition, which is why we set a sample size of 35 in each group of participants [34]. The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants were summarized using numbers and percentages for categorical variables. PA characteristics were included once, regardless of the number of patients they followed. Follow-up data only contains data from participants who have completed the intervention. Patient-reported outcome measures were summarized using mean and standard deviation (SD). Official scoring manuals including guidelines for handling missing answers were used for computation of subscale scores. Data from one item of the FACT-LEU scale was not collected and is treated as a missing value for all participants when computing the subscale score. A linear mixed-effect model with random effect of participants and fixed effect of assessment time was used to analyze changes between baseline to 12-week follow-up and between the 12- and 24-week follow-up. The Wald test was used to test the hypothesis that changes equal to zero. P values < 0.05 were used to determine statistical significance, and the data analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 25 and R [35].

Results

Participant characteristics

In total, 36 patients and 24 PAs were included (Table 1). Females made up 58.3% of patients and 50% of PAS, while the age range was 21–77 (mean age, patients: 54.5 years; PAs: 51.5 years). PAs were slightly more frequently married or living with a partner compared to patients. Acute myeloid leukemia was the most frequent diagnosis in both patients (66.7%) and PAs (50.0%). A little less than half (44%) of the PAs were more than 4 years from their AL diagnosis, and 68% had undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Feasibility criteria

Acceptability

A total of 53 eligible patients were approached (Fig. 1), 36 of whom were accepted for participation, and 17 of whom declined participation, mainly due to the following: a lack of physical and/or psychological strength to participate; already had enough support from own network; comorbidities; did not want to become immersed in their own disease; and did not want to involve unfamiliar parties in the course of their disease and treatment. Four patients were lost to follow-up due to transition to terminal care (n = 1), death (n = 2), and withdrawal (n = 1). In total, 32 patients completed the intervention. A total of 82 eligible PAs were approached (Fig. 2), 35 of whom agreed to participate, and 25 of whom were enrolled in the intervention. After enrollment, six PAs were lost to follow-up due to relapse, their patient died, was transferred to terminal care, or withdrew. In total, 24 PAs completed the intervention, and 12 participated more than once. Patients and PAs were largely satisfied with the intervention, with 96.3% of patients (n = 27) and 80.6% of PAs (n = 31) reporting a satisfaction level ≥ 5 out of 10. The intervention also had an acceptable influence on the patient’s disease and treatment trajectory, with 74.0% reporting ≥ 5 out of 10 points.

Practicability

All 35 enrolled PAs participated in the mandatory educational 6-hour program prior to the intervention. The PA course was reported useful (86.6%) in relation to what they experienced, and the majority (93.3%) reported receiving enough information and knowledge about their new role. Throughout the intervention, 10 network meetings were held, with participation at each meeting reaching three to 13 PAs.

Meeting personally with patients was challenging, primarily because of the patients’ lack of strength, hospitalization, reduced immune system, many visits from their own social network, or geographical distance. Only 9.3% had four personal meetings during the intervention, 3.1% had three meetings, 3.1% had two, 21.9% one, and 62.5% none. There were 404 contacts between patients and PAs, with a mean of 12.6 contacts per dyad. The number of contacts was decreasing during the intervention, with a small increase at the end of the period (Fig. 3). Our data shows that text messages and telephone conversations were used the most to make contact. Figure 3 provides an overview of the distribution of conversation topics between participants during the intervention, with treatment the most common, followed by side effects, complications, everyday life, and family.

Safety and support

None of the PAs needed individual support from the project psychologist, and they only initiated contact with health professionals during the intervention. There were 16 PAs who initiated contact with the principle investigator, interspersed as follows: one contact (n = 7), two contacts (n = 2), three contacts (n = 3), four contacts (n = 2), and six contacts (n = 1). Reasons for contact were evaluation of initiating the relation; challenges in establishing the relationship; death of patient; and patient unsure of whether to stay in the intervention. PAs primarily found support in network meetings (76.5%), principle investigator (23.5%), and their spouse (17%). Reasons for seeking support were the need to talk with others and hear their experiences with the role of PA; managing challenges in establishing the relationship with the patient; and coping when the patient’s treatment failed. One patient ambassador experienced a relapse during the intervention, causing the patient concern because the patient ambassador functioned as a beacon of hope for the future. The worry did not persist, and the patient and principle investigator jointly decided that she did not need further support. However, the new circumstances meant that they maintained contact and took a more equal role. No unexpected adverse events occurred during the intervention.

Clinical outcome

We studied multiple patient-reported outcome variables, which are listed for patients in Table 2 and for PAs in Table 3. An overall trend showed that patients improved in all sum scores over time, from baseline to week 24. The patient’s mean score was above the cutoff score (> 8) for anxiety at baseline, but improved by 12-week follow-up, scoring below the cutoff point. For patients, statistically significant improvements from baseline to 12-week follow-up were found for anxiety (p = 0.007), global health (p = 0.047), role functioning (p = 0.014), cognitive functioning (p = 0.044), functional well-being (p = 0.014), and patient activation level (p = 0.021). Conversely, PAs did not change significantly over time in any of the clinical outcomes, with the exception of emotional well-being (p = 0.004) from baseline to 12-week follow-up.

Discussion

Discussion of results

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate a one-to-one peer support intervention in newly diagnosed patients with AL. The findings demonstrate that PAS was feasible and safe in this population, with high acceptability and satisfaction among both patients and PAs. However, there were challenges related to the wide amount of variation in how the support was provided, and in terms of the high disease and treatment-related symptom burden, emphasizing the importance of individualizing support in clinical practice. Support for the PAs was an indispensable aspect of the PAS program. Likewise, our qualitative evaluation of PAS showed that patients experienced a feeling of being understood, a cohesive relationship leading to hope and a feeling of being able to cope with their situation. Simultaneously, patient ambassadors experienced a sense of meaningfulness and gratitude for life [15].

This study demonstrated that PAS can be conducted in patients with AL undergoing intensive chemotherapy. Similar to other studies exploring peer support in cancer populations, we found the intervention to be acceptable, with high satisfaction among both patients and PAs [20, 21]. This may be explained by the benefits of social comparison processes, which play a pivotal role in understanding how people interpret health threats, understand their own health risks, and adapt to serious illness [18]. People facing a life-threatening disease may be compelled to use comparison as a way to counteract these issues [36]. Studies have revealed that patients with cancer prefer contact with, and information about, other cancer patients whose health is better than their own [37,38,39]. This upward social comparison may positively impact newly diagnosed patients during peer support because they can clarify what has happened (and is happening) to them, be assured by those who have survived the disease and treatment, and share their experiences with others [37,38,39].

In contrast, PAs may use downward comparisons to put their own disease trajectory into perspective by evaluating themselves against those perceived to be in poorer health, in this case the patients [36]. Regardless, if the difference between people is too significant, it may result in alienation, with no possibility of comparison [18]. Therefore, matching in peer support interventions is of great importance to achieve successful comparison between two peers. In our study, we matched participant preferences as closely as possible, which may explain the low dropout rate and the high satisfaction among both groups of participants.

Our results showed that patients improved over time in most psychosocial outcomes, which is consistent with other longitudinal studies examining QOL and psychological health in patients with AL throughout the treatment trajectory [40,41,42]. Although scores improved over time, the results were still significantly lower compared to normative data [43]. This highlights the importance of developing and undertaking interventions that improve QOL and psychosocial outcomes in patients with AL. Interestingly, PAs who maintained their psychosocial origin had QOL levels that were equal to or better than normative data [43]. This indicates two important perspectives to recognize in peer support interventions. First, PAs may benefit from their role as a peer supporter, and the role becomes a part of their own long-term psychological recovery. This has been confirmed in previous studies where peer supporters achieve a positive impact by putting their own disease trajectory and life experiences into perspective [14, 19, 21]. Second, PAs represent a selected group of peers who are psychologically robust, which is important as those who wish to participate are best suited for the role of peer supporter.

Several systematic reviews have examined the impact of peer support in cancer populations [20, 21, 44, 45]. However, depending on the cancer population, there is contradictory evidence on the provision of peer support [20]. Our results suggest that PAS in patients with AL should be provided individually as patients have different needs that change over time, depending on their disease trajectory and symptom burden. These results are in line with the general perspective of patient-centered care, which focuses on the individual’s particular health care needs and preferences [46].

Due to the peer supporter’s history of cancer and thus risk of increased vulnerability, monitoring their psychosocial status is imperative [20]. Our results demonstrate that psychosocial status in PAs does not change over time during their role as peer supporters, and none of the PAs took advantage of the opportunity to speak individually with the psychologist. This result should be viewed in the light of the tremendous effort that was put into preparing and supporting the PAs throughout the intervention. In line with this, a qualitative study (2013) exploring the experiences of peer supporters found no adverse consequences but emphasized the importance of providing support and training [19].

There is an indication that peer supporters perceive their support as being less effective and supportive than the peer support recipients did [45]. This potential discrepancy may explain why the PAs in the present study were less satisfied compared to the patients. Similar results were found in a previous qualitative study exploring the experiences of cancer patients and their peer supporters that showed that peer supporters found it challenging to strike the right balance between their own need to help and the patient’s need for help [14]. In a recent qualitative study, the motivation of PAs was explored and showed that their own disease course became meaningful, which facilitated a better recovery [47]. Therefore, taking their motivation and potential challenges into account is essential when training peer supporters.

Discussion of methods

The strengths of this study include the longitudinal design and inclusion of three centers, with close monitoring of feasibility and the psychosocial well-being of all participants. Limitations include that participants were primarily not living alone and were well-educated, which may limit the representativeness of our findings. Patient demographic data on non-participants was not collected, which is why we cannot confirm their comparability. However, only a small number of patients declined participation due to having a sufficient social network. We encountered missing data at 24 weeks, mostly in patients, although this was expected to some degree due to their prognosis and significant symptom burden. This may have led to an overestimation of the sum scores at this time point.

Clinical implications

Based on our results, we recommend PAS as a supplement to the existing supportive care service available to patients with AL. The PAs are not educated health care professionals, which is why it is essential that they receive the necessary education and support organized by an established network with collaboration between PAs, hospitals, and departments. Evidence is lacking on the timing, type, and duration of peer support, though many studies have assessed outcome measures such as coping, QOL, and psychological states without finding significant effects [20, 21]. This might suggest that these outcomes are not appropriate for assessing the effectiveness of peer support, and more immediate outcomes such as availability of social support could be more applicable in future research. Finally, the evidence to date is based on an examination of peer support provided either face-to-face, by telephone or as a group support. Our findings highlight the importance of providing individual support, and taking this approach is imperative to obtain high representativeness to initiate meaningful support that accommodates a broad group of patients.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that PAS in newly diagnosed patients with AL during initial treatment was feasible and safe. Patients and PAs reported high satisfaction with individual peer support, and patients’ psychosocial outcomes improved over time. PAs maintained psychosocial baseline levels, with no adverse events, and used the available support to exchange experiences with other PAs. The findings of this study have the potential to have an impact on psychosocial supportive care in patients with AL by informing the development of integrated psychosocial interventions. Our results are based on a sample of participants with AL, and future research is needed to confirm these results in patients and survivors with other hematological malignancies and cancers.

References

Short NJ, Rytting ME, Cortes JE (2018) Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet 392(10147):593–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31041-9

Zimmermann C, Yuen D, Mischitelle A, Minden MD, Brandwein JM, Schimmer A, Gagliese L, Lo C, Rydall A, Rodin G (2013) Symptom burden and supportive care in patients with acute leukemia. Leuk Res 37(7):731–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2013.02.009

Terwilliger T, Abdul-Hay M (2017) Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2017 update. Blood cancer journal 7(6):e577. https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2017.53

De Kouchkovsky I, Abdul-Hay M (2016) Acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2016 update. Blood cancer journal 6(7):e441. https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2016.50

Leak Bryant A, Lee Walton A, Shaw-Kokot J, Mayer DK, Reeve BB (2015) Patient-reported symptoms and quality of life in adults with acute leukemia: a systematic review. Oncol Nurs Forum 42(2):E91–e101. https://doi.org/10.1188/15.onf.e91-e101

Moller T, Nielsen OJ, Welinder P, Dunweber A, Hjerming M, Moser C, Kjeldsen L (2010) Safe and feasible outpatient treatment following induction and consolidation chemotherapy for patients with acute leukaemia. Eur J Haematol 84(4):316–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01397.x

Walter RB, Taylor LR, Gardner KM, Dorcy KS, Vaughn JE, Estey EH (2013) Outpatient management following intensive induction or salvage chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Clinical advances in hematology & oncology : H&O 11(9):571–577

Cannas G, Thomas X (2015) Supportive care in patients with acute leukaemia: historical perspectives. Blood transfusion = Trasfusione del sangue 13(2):205–220. https://doi.org/10.2450/2014.0080-14

Fridthjof KS, Kampmann P, Dunweber A, Gorlov JS, Nexo C, Friis LS, Norskov KH, Welinder PC, Moser C, Kjeldsen L, Moller T (2018) Systematic patient involvement for homebased outpatient administration of complex chemotherapy in acute leukemia and lymphoma. Br J Haematol 181(5):637–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.15249

Albrecht TA, Boyiadzis M, Elswick RK Jr, Starkweather A, Rosenzweig M (2016) Symptom management and psychosocial needs of adults with acute myeloid leukemia during induction treatment: a pilot study. Cancer Nurs 40:E31–E38. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc.0000000000000428

Albrecht TA, Rosenzweig M (2014) Distress in patients with acute leukemia: a concept analysis. Cancer Nurs 37(3):218–226. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e31829193ad

Gheihman G, Zimmermann C, Deckert A, Fitzgerald P, Mischitelle A, Rydall A, Schimmer A, Gagliese L, Lo C, Rodin G (2016) Depression and hopelessness in patients with acute leukemia: the psychological impact of an acute and life-threatening disorder. Psycho-oncology 25(8):979–989. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3940

Norskov KH, Overgaard D, Lomborg K, Kjeldsen L, Jarden M (2019) Patients’ experiences and social support needs following the diagnosis and initial treatment of acute leukemia-a qualitative study. European journal of oncology nursing : the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society 41:49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2019.05.005

Skirbekk H, Korsvold L, Finset A (2018) To support and to be supported. A qualitative study of peer support centres in cancer care in Norway. Patient Educ Couns 101(4):711–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.11.013

Nørskov KH, Overgaard D, Lomborg K, Kjeldsen L, Jarden M (2020) Patient ambassador support: experiences of the mentorship between newly diagnosed patients with acute leukaemia and their patient ambassadors. European journal of cancer care:e13289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13289

Ussher J, Kirsten L, Butow P, Sandoval M (2006) What do cancer support groups provide which other supportive relationships do not? The experience of peer support groups for people with cancer. Soc Sci Med 62(10):2565–2576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.034

Festinger L (1954) A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat 7(2):117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Suls J, Miller R (1977) Social comparison theory and research: an overview from 1954. In: Social Comparison Processes. John Wiley & Sons, London pp. 1–17

Pistrang N, Jay Z, Gessler S, Barker C (2013) Telephone peer support for women with gynaecological cancer: benefits and challenges for supporters. Psycho-oncology 22(4):886–894. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3080

Hoey LM, Ieropoli SC, White VM, Jefford M (2008) Systematic review of peer-support programs for people with cancer. Patient Educ Couns 70(3):315–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.016

Meyer A, Coroiu A, Korner A (2015) One-to-one peer support in cancer care: a review of scholarship published between 2007 and 2014. European journal of cancer care 24(3):299–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12273

Piil K, Jarden M, Pii KH (2019) Research agenda for life-threatening cancer. European journal of cancer care 28(1):e12935. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12935

Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, Cofta-Woerpel L, Linnan L, Weiner D, Bakken S, Kaplan CP, Squiers L, Fabrizio C, Fernandez M (2009) How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med 36(5):452–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002

Orsmond GI, Cohn ES (2015) The distinctive features of a feasibility study: objectives and guiding questions. OTJR : occupation, participation and health 35(3):169–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449215578649

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

Cella D, Jensen SE, Webster K, Hongyan D, Lai JS, Rosen S, Tallman MS, Yount S (2012) Measuring health-related quality of life in leukemia: the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy--Leukemia (FACT-Leu) questionnaire. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research 15(8):1051–1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2210

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85(5):365–376

Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Chou C, Harle MT, Morrissey M, Engstrom MC (2000) Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer 89(7):1634–1646

Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M (2004) Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 39(4 Pt 1):1005–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x

Rademakers J, Maindal HT, Steinsbekk A, Gensichen J, Brenk-Franz K, Hendriks M (2016) Patient activation in Europe: an international comparison of psychometric properties and patients’ scores on the short form Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13). BMC Health Serv Res 16(1):570. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1828-1

Johnston M WS, Weinman J (1995) Measures in health psychology: a user’s portfolio. Windsor: NFER-NELSON, UK

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, Duda SN (2019) The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 95:103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42(2):377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Billingham SA, Whitehead AL, Julious SA (2013) An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom Clinical Research Network database. BMC Med Res Methodol 13:104. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-104

The R Project for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed April 25 2020

Guyer JV-J, Thomas. (2018) Upward and downward social comparisons: a brief historical overview. In: V. Zeigler-Hill TKS (ed) Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Springer International Publishing

Moulton A, Balbierz A, Eisenman S, Neustein E, Walther V, Epstein I (2013) Woman to woman: a peer to peer support program for women with gynecologic cancer. Soc Work Health Care 52(10):913–929. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2013.834031

Mirrielees JA, Breckheimer KR, White TA, Denure DA, Schroeder MM, Gaines ME, Wilke LG, Tevaarwerk AJ (2017) Breast cancer survivor advocacy at a university hospital: development of a peer support program with evaluation by patients, advocates, and clinicians. Journal of cancer education : the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education 32(1):97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0932-y

Lee R, Lee KS, Oh EG, Kim SH (2013) A randomized trial of dyadic peer support intervention for newly diagnosed breast cancer patients in Korea. Cancer Nurs 36(3):E15–E22. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182642d7c

Alibhai SM, Breunis H, Timilshina N, Brignardello-Petersen R, Tomlinson G, Mohamedali H, Gupta V, Minden MD, Li M, Buckstein R, Brandwein JM (2015) Quality of life and physical function in adults treated with intensive chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia improve over time independent of age. Journal of geriatric oncology 6(4):262–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2015.04.002

Moller T, Adamsen L, Appel C, Welinder P, Stage M, Jarden M, Hjerming M, Kjeldsen L (2012) Health related quality of life and impact of infectious comorbidity in outpatient management of patients with acute leukemia. Leukemia & lymphoma 53(10):1896–1904. https://doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2012.676169

Jarden M, Moller T, Christensen KB, Kjeldsen L, Birgens HS, Adamsen L (2016) Multimodal intervention integrated into the clinical management of acute leukemia improves physical function and quality of life during consolidation chemotherapy: a randomized trial ‘PACE-AL’. Haematologica 101(7):e316–e319. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2015.140152

Nolte S, Liegl G, Petersen MA, Aaronson NK, Costantini A, Fayers PM, Groenvold M, Holzner B, Johnson CD, Kemmler G, Tomaszewski KA, Waldmann A, Young TE, Rose M (2019) General population normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 health-related quality of life questionnaire based on 15,386 persons across 13 European countries, Canada and the Unites States. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 107:153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2018.11.024

Campbell HS, Phaneuf MR, Deane K (2004) Cancer peer support programs-do they work? Patient Educ Couns 55(1):3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2003.10.001

Macvean ML, White VM, Sanson-Fisher R (2008) One-to-one volunteer support programs for people with cancer: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns 70(1):10–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.08.005

Flagg AJ (2015) The role of patient-centered care in nursing. The Nursing clinics of North America 50(1):75–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2014.10.006

Myrhoj CB, Norskov KH, Jarden M, Rydahl-Hansen S (2020) The motivation to volunteer as a peer support provider to newly diagnosed patients with acute leukemia-a qualitative interview study. European journal of oncology nursing : the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society 46:101750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101750

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients who participated in this study. We also acknowledge the volunteer participation of the patient ambassadors and their passion for helping other patients with AL by sharing their experiences. This study is part of the Models of Cancer Care Research Program at Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, funded by Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Funding

This study was supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (grant number NNF17OC0030072).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Funding acquisition: Kristina Holmegaard Nørskov, Mary Jarden; conceptualization: Kristina Holmegaard Nørskov, Dorthe Overgaard, Lars Kjeldsen, Mary Jarden; methodology: Kristina Holmegaard Nørskov, Dorthe Overgaard, Anders Tolver, Kirsten Lomborg, Lars Kjeldsen, Mary Jarden; investigation: Kristina Holmegaard Nørskov, Jannie Boesen, Anne Struer, Sarah Elke Weber Due El-Azem; data curation: Kristina Holmegaard Nørskov, Anders Tolver, Mary Jarden; formal analysis: Kristina Holmegaard Nørskov, Anders Tolver, Mary Jarden; resources: Kristina Holmegaard Nørskov, Mary Jarden; Software: Kristina Holmegaard Nørskov, Mary Jarden; supervision: Mary Jarden, Dorthe Overgaard, Lars Kjeldsen, Kirsten Lomborg; validation: Dorthe Overgaard, Anders Tolver, Kirsten Lomborg, Lars Kjeldsen, Mary Jarden; visualization: Kristina Holmegaard Nørskov, Mary Jarden; writing—original draft: Kristina Holmegaard Nørskov; writing—review and editing: Dorthe Overgaard, Jannie Boesen, Anne Struer, Sarah Elke Weber Due El-Azem, Anders Tolver, Kirsten Lomborg, Anders Tolver, Mary Jarden.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study, which was approved by Copenhagen University of Hospital’s ethics committee (58097, 19-04-2017), adheres to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

The participants provided informed consent regarding publishing () data in this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The corresponding author has full control of all primary data and agrees to allow the journal to review their data if requested.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nørskov, K.H., Overgaard, D., Boesen, J. et al. Patient ambassador support in newly diagnosed patients with acute leukemia during treatment: a feasibility study. Support Care Cancer 29, 3077–3089 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05819-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05819-w