Abstract

Purpose

To investigate lifestyle in a population-based sample of long-term (≥ 5 years since diagnosis) young adult cancer survivors (YACSs), and explore factors associated with not meeting the lifestyle guidelines for physical activity (PA), body mass index (BMI), and smoking.

Methods

YACSs (n = 3558) diagnosed with breast cancer (BC), colorectal cancer (CRC), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), or localized malignant melanoma (MM) between the ages of 19 and 39 years and treated between 1985 and 2009 were invited to complete a mailed questionnaire. Survivors of localized MM treated with limited skin surgery served as a reference group for treatment burden.

Results

In total, 1488 YACSs responded (42%), and 1056 YACSs were evaluable and included in the present study (74% females, average age at survey 49 years, average 15 years since diagnosis). Forty-four percent did not meet PA guidelines, 50% reported BMI ≥ 25 and 20% smoked, with no statistically significant differences across diagnostic groups. Male gender, education ≤ 13 years, comorbidity, lymphedema, pain, chronic fatigue, and depressive symptoms were associated with not meeting single and/or an increasing number of lifestyle guidelines.

Conclusion

A large proportion of long-term YACSs do not meet the lifestyle guidelines for PA, BMI, and/or smoking. Non-adherence to guidelines is associated with several late effects and/or comorbidities that should be considered when designing lifestyle interventions for YACSs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Each year, approximately 130,000 individuals aged 20 to 39 years are diagnosed with cancer in Europe [1]. Improvements in detection and treatment have led to a relative 5-year survival rate of more than 80%, thus creating a rapidly growing population of long-term (≥ 5 years since diagnosis) young adult cancer survivors (YACSs) [2, 3]. Their life-saving treatment, however, places long-term YACSs at risk of late effects, such as fatigue, cardiovascular diseases, and second cancer [3,4,5].

Physical activity (PA), a healthy body mass index (BMI), and non-smoking are associated with a lower risk of cancer recurrence, morbidity, and mortality [6,7,8], and are considered key components to improve and preserve long-term health among cancer survivors [9]. Furthermore, healthy lifestyle behaviors (and conversely, unhealthy behaviors) are likely to cluster within individuals, e.g., those who are physically active are likely to not smoke [10]. Meeting several lifestyle guidelines provides superior health benefits compared with meeting only a single guideline [9]. Similar to the population in general, cancer survivors are therefore recommended to be physically active for at least 150 min with moderate intensity or 75 min with high intensity per week, maintain a healthy BMI, avoid smoking, and consume at least five daily servings of vegetables and fruits (“5-a-day”) [11, 12].

Despite the well-known health benefits of meeting these guidelines, a large proportion of cancer survivors are physically inactive, overweight and do not meet “5-a-day”, and few cancer survivors meet multiple lifestyle guidelines (7–40%) [10, 13]. To date, research on lifestyle in cancer survivors is predominantly based on populations diagnosed with cancer after the age of 50, examined less than 5 years since diagnosis [10, 13]. Although a cancer diagnosis may immediately motivate individuals to live a more healthy life [9], little is known about the lifestyle of those surviving 5 years and beyond.

The few studies which have investigated lifestyle in YACSs have also mostly included populations less than 5 years since diagnosis [14,15,16]. Two recent studies from the USA investigated lifestyle exclusively among long-term adolescent and YACSs, and found that 56–65% were not meeting the PA guidelines, and one in three were smoking [17, 18]. Generalizability of these US findings to European long-term YACS is, however, questionable due to differences in culture and health care systems.

For long-term YACSs, empirical knowledge on their lifestyle is lacking. To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated the adherence to multiple lifestyle guidelines in long-term YACSs. Demographic characteristics, such as male gender, older age, and low education have been linked to unhealthy lifestyle behaviors among survivors diagnosed with cancer at a young age [19], but associations between lifestyle and cancer treatments and late effects, as well as other health characteristics, are scarcely explored in long-term YACSs. One might hypothesize that some groups of long-term YACSs might be more susceptible to an unhealthy lifestyle than others, e.g., a high treatment burden with subsequent late effects such as fatigue might limit individuals in meeting the PA guidelines. Knowledge on demographic, cancer-related, and health characteristics of those with an unhealthy lifestyle is required in order to identify subgroups that might need particular support, and to develop effective lifestyle interventions for long-term YACSs [15, 16].

On this background, the overall aim of the present study was to investigate lifestyle among long-term YACSs, based on data from a large population-based cross-sectional survey named The Norwegian childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivor study (The NOR-CAYACS study) [20]. Specific aims were to:

-

1)

Investigate the adherence to lifestyle guidelines among Norwegian long-term YACSs treated for breast cancer (BC), colorectal cancer (CRC), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), or localized malignant melanoma (MM).

-

2)

Explore demographic, cancer-related, and health characteristics associated with not meeting single and an increasing number of guidelines for PA, BMI, and smoking.

Based on existing knowledge about lifestyle in other populations of cancer survivors, we hypothesized that most YACSs would not meet PA guidelines and/or be overweight, but that a minority would be smoking. Moreover, we hypothesized that low level of education, comorbid conditions, and late effects would be associated with not meeting lifestyle guidelines.

Methods

Design and study population

Details on study design and population have been described previously [20]. In brief, 3558 YACSs diagnosed with BC, CRC, NHL, or ALL, as well as a randomly selected subsample of MM, between the ages of 19 and 39 years during 1985–2009 were identified by the Cancer Registry of Norway (CRN), and invited to participate in a postal questionnaire-based survey. The selection of the cancer diagnoses was based on their relative frequent occurrence during young adulthood, on the good prognosis and the relatively high risk of late effects. YACSs of other relevant cancer types such as testicular cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, and cervical cancer were not invited because survivors after these diagnoses already participated in other ongoing studies at our research unit at the time of survey. Exclusion criteria for the present study are described in Fig. 1.

Variables and measurements

Lifestyle

Physical inactivity was defined as not meeting the guidelines of ≥ 150 min of moderate intensity PA or 75 min high intensity PA, or an equivalent combination of moderate and high intensity PA per week [11], using a modified version of the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) [21]. The GLTEQ assesses the average frequency and number of minutes of mild, moderate, and vigorous leisure time PA during a typical week. The number of minutes within the different intensity levels of PA were calculated for each participant, and used to classify individuals as physically active (≥ 150 min of moderate intensity or ≥ 75 min of vigorous intensity per week) or inactive according to the PA guidelines.

BMI (kg/m2) was calculated from self-reported height and body weight, and categorized according to the World Health Organization’s categorization of BMI in adults, healthy weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), and overweight/obese (> 25.0–29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) [22].

“5-a-day” was assessed by a question modified from the Nord-Trøndelag Health (HUNT) study [23], asking the participants how often they consume at least five daily servings of vegetables, fruits, and berries. Responses were categorized into meeting “5-a-day” (every day) and not meeting “5-a-day” (4–6 days per week/1–3 days per week/less than 1 day per week). Nutrition guidelines are complex, and for this paper, we chose to only include the measure on “5-a-day,” which has shown to be associated with other healthy eating habits [24].

Current smoking was assessed by the question “Do you smoke?”, from the HUNT study [23]. Responses were dichotomized into yes (smoking daily or smoking now and then) versus no (discontinued smoking/never smoked).

A more unhealthy lifestyle: the number of lifestyle guidelines not met (physically inactive, BMI ≥ 25 and smoking) were summed for each participant (0 to 3). Because of the large proportion not meeting “5-a-day” (92%), “5-a-day” was not included in the score of a more unhealthy lifestyle.

Explanatory variables

Participants self-reported on demographic, cancer treatment, and health variables, while information on cancer type and initial stage was obtained from the CRN.

Living with a partner included marriage and cohabitation. Education level was dichotomized into ≤ 13 years (up to high school) versus > 13 years (college/university).

Treatment intensity was categorized as (1) limited surgery for localized MM (surgical removal of the skin lesion), (2) surgery and/or radiotherapy, (3) systemic treatment only, and (4) systemic treatment combined with surgery and/or radiotherapy.

Number of comorbid conditions was assessed using a modified version of the Charlson comorbidity index [25]. For each participant, the number of the following comorbid conditions ever experienced was summed and categorized as “no comorbidity,” “1–2 comorbid conditions,” and “> 2 comorbid conditions”: cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, diabetes, kidney disease, gastro-intestinal disease, rheumatic disease, arthrosis, muscle/joint pain, epilepsy, and thyroid diseases.

Presence of numbness in hands/feet and lymphedema were categorized as yes/no. Pain was assessed by the pain item in the 12-Item Short Form Survey (SF-12) [26]. Responses were dichotomized as no (“not at all”/“a little bit”/“moderately”) versus yes (“quite a bit”/“extremely”). Using questions modified from the HUNT study [23], trouble sleeping was defined as experiencing one or more of the following three problems several times per week: “difficulties falling asleep at night,” “waking up repeatedly during the night,” and/or “waking up too early without being able to go back to sleep.”

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which corresponds to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorders [27].The PHQ-9 contains 9 items. The frequency of experienced depressive symptoms during the last 2 weeks with response categories ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) is assessed. Increasing sum score (0 to 27) indicates higher level of depressive symptoms. Anxiety symptoms were measured by the seven-item anxiety subscale of The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A) [28], with response categories from 0 (not present) to 3 (highly present). An increasing sum score (0 to 21) indicates higher level of anxiety symptoms. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.87 for PHQ-9 and 0.83 for HADS-A in the present study population. HADS-A was used to assess level of anxiety symptoms.

Chronic fatigue was assessed by the Fatigue Questionnaire (FQ) [29]. FQ contains 11 items distributed on two subscales: physical fatigue (7 items) and mental fatigue (4 items). Each item is scored from 0 to 3, with increasing total score (0 to 33) implying higher levels of fatigue. To identify chronic fatigue, raw scores of each item were dichotomized (0 = 0, 1 = 0, 2 = 1, 3 = 1). Chronic fatigue was defined by a dichotomized sum score ≥ 4 and ≥ 6 months duration of fatigue [29]. Cronbach’s alphas for the present study population were 0.91 (physical subscale), 0.84 (mental subscale), and 0.92 (the whole scale).

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were described using mean and standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. Comparisons across diagnostic groups were performed with chi-square tests or one-way analysis of variance. Logistic regression analyses identified factors associated with not meeting single guidelines of PA, overweight, and smoking. Ordinal regression analyses were applied to identify factors associated with an increasing number of unhealthy lifestyle factors in terms of physical inactivity, overweight, and smoking (0 to 3), referred to as a more unhealthy lifestyle. Variables statistically significant associated with the dependent variable in unadjusted analyses (p < 0.05) were included as independent variables in the multivariable regression analyses. Limited surgery for localized MM was used as a reference group for treatment burden in the regression analyses.

All independent variables included in multivariable analyses were checked for multicollinearity, and all correlation coefficients were < > 0.8). Because of overlapping content in the items in FQ and PHQ-9, only chronic fatigue was included in multivariable analyses if both fatigue and depressive symptoms were statistically significant associated with the dependent variable in unadjusted analyses. For the ordinal regression analyses, the proportional odds assumption was confirmed by the test of parallel lines. Results from the multivariable analyses were presented as adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics version 25.0.

Compliance with ethical standards

The NOR-CAYACS study was approved by the South East Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (no: 2015/232), the Norwegian Data Protection Authority (no: 15/00395-2/CGN), the Data Protection Officer at Oslo University Hospital and the CRN. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Results

Characteristics of participants

A total of 1488 (42%) YACSs responded. After exclusion of 432 responders, 1056 evaluable participants were retained (Fig. 1). Characteristics of evaluable responders versus non-responders are described in the online resource file.

Characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. In brief, 74% were female, 40% diagnosed with BC, 11% CRC, 16% NHL, 10% ALL, and 23% MM. Mean age at survey was 49.0 years (SD 7.7), and mean time since diagnosis was 15.2 years (SD 6.8). Forty-seven percent of the participants had received systemic treatment in combination with surgery and/or radiotherapy and 72% reported at least one comorbid condition.

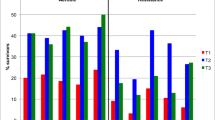

Adherence to lifestyle guidelines

Among all YACSs, 44% were physically inactive, 50% were overweight, 20% were current smokers, and 92% did not consume “5-a-day” (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences across the diagnostic groups (Table 2). Twenty-six percent met all three guidelines for PA, BMI, and smoking (Table 2).

Factors associated with not meeting lifestyle guidelines

Factors associated with physical inactivity, overweight, or smoking in unadjusted analyses are shown in Table 3.

In multivariable analyses, only chronic fatigue remained associated with physical inactivity (aOR 1.50, 95% CI 1.11–2.03) (Table 3). Male gender (aOR 2.50, 95% CI 1.80–3.45), > 2 comorbid conditions (aOR 1.99, 95% CI 1.31–3.04), lymphedema (aOR 1.77, 95% CI 1.25–2.50), and increasing levels of depressive symptoms (aOR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.06) were associated with being overweight. Systemic treatment combined with surgery and/or radiotherapy was negatively associated with overweight (aOR 62, 95% CI 0.44–0.89). Living without a partner (aOR 1.50, 95% CI 1.02–2.21), education ≤ 13 years (aOR 1.63, 95% CI 1.18–2.27) and lymphedema (aOR 1.67, 95% CI 1.15–2.41) were positively associated with smoking (Table 3).

Factors associated with a more unhealthy lifestyle in unadjusted analyses are shown in Table 4. Male gender (aOR 1.80, 95% CI 1.37–2.37), education ≤ 13 years (aOR 1.44, 95% CI 1.13–1.84), > 2 comorbid conditions (aOR 1.57, 95% CI 1.08–2.29), lymphedema (aOR 1.37, 95% CI 1.02–1.84), and pain (aOR 1.54, 95% CI 1.0–2.35) were associated with a more unhealthy lifestyle in multivariable ordinal regression analyses.

Discussion

This large population-based study on lifestyle among long-term YACSs shows that the majority of long-term YACSs are physically inactive, overweight, and/or not meeting “5-a-day,” and that one in five are smokers. Only one in four YACSs meet the combination of PA, BMI, and smoking guidelines. Non-adherence to lifestyle guidelines is associated with male gender, living without a partner, education ≤ 13 years, comorbid conditions, lymphedema, pain, increasing levels of depressive symptoms, and/or chronic fatigue.

Importantly, the diversity of measures, population characteristics, and cultural differences across studies limit direct comparison of our findings with previous results on lifestyle among cancer survivors. Taking this into account, long-term YACSs in our study seemed to be overall equally or more adherent to lifestyle guidelines than cancer survivors in general [10, 13, 15, 17, 19]. Compared with our finding that 44% of YACSs are physically inactive, Warner et al. reported physical inactivity in 56–65% of US long-term adolescent and YACSs [17]. Also, the proportion not meeting PA guidelines in our study is lower than findings among survivors diagnosed with cancer at an older age (50–75%) [10, 13, 30]. In agreement with our findings, and using the same PA questionnaire, Bélanger et al. [15] found that 48% were physically inactive among Canadian YACSs of various cancer types diagnosed between the ages of 20 to 44 years. However, most of these participants were not long-term survivors (i.e., < 5 years since diagnosis).

The prevalence of overweight in our study (50%) is also in agreement with findings in Bélanger et al.’s study (53%) [15], and with findings in US survivors of BC and CRC diagnosed before the age of 50 and examined almost 10 years after diagnosis (55%) [31]. Higher proportions of overweight have been found among survivors diagnosed with cancer further into adulthood (60–75%) [13, 30]. The proportion of 20% smokers in our study was lower than reported among female adolescent survivors and YACSs in US studies (≈ 30%) [17, 18], but higher than found among older adult cancer survivors and the YACSs in the study by Bélanger et al. (13%) [13, 15].

Our results are also similar to the self-reported prevalence of overweight (48%) and smoking (women 17%, men 22%) in the general Norwegian general population, while the proportion of physically inactive individuals in the general population (33%) is somewhat lower than among the YACSs (44%) [32, 33].

Furthermore, 92% of the participants in our study did not meet “5-a-day,” which is congruent with findings among the adolescent and YACSs in the study by Warner et al. [17] (up to 89% not meeting “5-a-day”) and the general Norwegian population (86%) [34]. In other populations of cancer survivors, somewhat higher proportions of survivors eating “5-a-day” have been reported (30–45%) [31, 35]. Given that close to all participants in our sample were not meeting “5-a-day,” we chose to not explore associated factors. A broader exploration of nutrition, e.g., guidelines on red meat, fish, sodium, and added sugar, would probably provide more information about the characteristics of long-term YACSs not meeting nutrition guidelines.

Assuming that long-term YACSs are aware of their risk for late effects following treatment, one could expect that they would be more motivated for having a healthy lifestyle than the general population. Due to their low treatment burden, one might hypothesize that survivors of localized MM would be more comparable to the population in general than to YACSs with a higher cancer treatment burden. However, adherence to lifestyle guidelines did not differ across the diagnostic groups in our study.

In sum, our findings suggest that despite their increased risk of a poorer health, long-term YACSs do not seem more likely of having a healthy lifestyle than the general population. One explanation for this might be lack of knowledge about the importance of a healthy lifestyle and their risk of late effects. In Norway, systemic follow-up programs including information on lifestyle issues for cancer survivors are lacking. Previous research has demonstrated limited knowledge about late effects among both cancer survivors [36] and general practitioners (GPs) [37]. Furthermore, in a recent systematic review, Tollosa et al. found that survivors 5 years or less from diagnosis had better health behavior than long-term survivors [13], suggesting that it is challenging to maintain a healthy lifestyle after cancer as time goes by. Moreover, as some late effects appear several years after treatment, cancer survivors might not be motivated for a healthy lifestyle until potential health problems occur. To the contrary, poor health and late effects after cancer may also limit the ability to obtain or maintain a healthy lifestyle [38].

Lifestyle interventions in cancer survivors must be targeted towards their unique needs and challenges [9]. We found that chronic fatigue was associated with not meeting PA guidelines, which is in line with previous research on fatigue and PA in survivors of lymphoma [39], CRC [40] and BC [41]. Fatigue is also one of the most commonly reported barriers for PA among cancer survivors in general [38]. PA is, however, also recommended to improve fatigue among cancer survivors, as physical inactivity and subsequent loss of muscle mass and physical function may worsen fatigue symptoms [42].

Also in agreement with previous findings among cancer survivors in general, being overweight in the present study was associated with male gender [30], comorbid conditions [39], and depressive symptoms [19]. We found that long-term YACSs who had received multimodal therapy were less likely to be overweight than MM survivors treated with limited surgery. This is in line with the findings in a recent study by our group reporting that receipt of three or more treatment regimens was associated with a decreased risk of being overweight in long-term lymphoma survivors treated with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support [39]. However, research in BC survivors has reported large variations in weight change (gain, maintenance, and loss) during and after adjuvant systemic treatments [43].

The finding that only one in four long-term YACSs met all guidelines with regard to PA, BMI, and non-smoking is comparable with the results in the study by Spector et al., showing that 20% of older long-term NHL survivors met these three guidelines [35]. Also congruent with our findings, Tollosa et al. estimated that 23% of adult cancer survivors met a combination of several lifestyle recommendations [13]. Considering their long life-expectancy with risk of late effects and future health challenges associated with aging, adhering to a combination of multiple lifestyle guidelines might be particularly important for YACSs.

Our findings indicate a need to inform YACSs and health personnel involved in the follow-up of YACSs about the benefits of a healthy lifestyle also as a preventive measure against late effects. Such information may be conveyed through courses for cancer survivors and health personnel involved in the follow-up care of cancer survivors, and by establishing guidelines for lifestyle advice as part of follow-up. Moreover, focus on lifestyle and long-term health should be implemented in individual care plans and patient information (brochures/electronically). Patients should receive information or counseling about the benefits of a healthy lifestyle in a manner tailored to their needs and health literacy levels.

The main strength of this study is the large national population-based sample of YACSs, which is an understudied population in terms of long-term cancer survivorship [44]. Our study contributes with new knowledge about lifestyle and its associations to late effects, assessed with established patient-reported outcome measures. Such measures are essential to capture patient perspectives and symptoms that are subjective in nature and may lack universal diagnostic criteria (e.g., fatigue) [45]. Limitations include the cross-sectional design precluding causal conclusions, and the reliance on self-reported treatment data. The response rate of 42% and the high proportion of females and BC survivors might increase the risk of bias. However, Lie et al. recently found low risk of non-response bias in the NOR-CAYACS study on a wide range of survey outcomes, including lifestyle [20].

Conclusion

Many long-term YACSs are not meeting one or more of the public guidelines for PA, BMI, and smoking. Health personnel involved in the follow-up of YACSs must have knowledge and focus on late effects and healthy lifestyle behaviors. YACSs with male gender, who are living without a partner, with education ≤ 13 years, comorbid conditions, lymphedema, pain, increasing levels of depressive symptoms, and/or chronic fatigue might have an increased risk of not meeting one or more of these guidelines. YACSs with these characteristics might need special attention to achieve and maintain a healthy lifestyle.

Data availability

The authors have full control of all primary data and the journal may review the data if requested.

References

Fidler MM, Gupta S, Soerjomataram I et al (2017) Cancer incidence and mortality among young adults aged 20–39 years worldwide in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 18(12):1579–1589. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30677-0

Keegan TH, Ries LA, Barr RD, Geiger AM, Dahlke DV, Pollock BH, Bleyer WA, National Cancer Institute Next Steps for Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Epidemiology Working Group (2016) Comparison of cancer survival trends in the United States of adolescents and young adults with those in children and older adults. Cancer 122(7):1009–1016. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29869

Barr RD, Ferrari A, Ries L, Whelan J, Bleyer WA (2016) Cancer in adolescents and young adults: a narrative review of the current status and a view of the future. JAMA Pediatr 170(5):495–501. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4689

Woodward E, Jessop M, Glaser A, Stark D (2011) Late effects in survivors of teenage and young adult cancer: does age matter? Ann Oncol 22(12):2561–2568. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdr044

Bohn SH, Thorsen L, Kiserud CE et al. (2019) Chronic fatigue and associated factors among long-term survivors of cancers in young adulthood. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden) 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186x.2018.1557344

Chan DS, Vieira AR, Aune D, Bandera EV, Greenwood DC, McTiernan A, Navarro Rosenblatt D, Thune I, Vieira R, Norat T (2014) Body mass index and survival in women with breast cancer-systematic literature review and meta-analysis of 82 follow-up studies. Ann Oncol 25(10):1901–1914. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu042

Friedenreich CM, Neilson HK, Farris MS, Courneya KS (2016) Physical activity and cancer outcomes: a precision medicine approach. Clin Cancer Res 22(19):4766–4775. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-16-0067

Foerster B, Pozo C, Abufaraj M, Mari A, Kimura S, D'Andrea D, John H, Shariat SF (2018) Association of smoking status with recurrence, metastasis, and mortality among patients with localized prostate cancer undergoing prostatectomy or radiotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 4(7):953–961. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1071

Demark-Wahnefried W, Rogers LQ, Alfano CM, Thomson CA, Courneya KS, Meyerhardt JA, Stout NL, Kvale E, Ganzer H, Ligibel JA (2015) Practical clinical interventions for diet, physical activity, and weight control in cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 65(3):167–189. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21265

Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K (2008) Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol 26(13):2198–2204. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.14.6217

Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W et al (2012) Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 62(4):242–274. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21142

Helsedirektoratet (2014) Anbefalinger om kosthold, ernæring og fysisk aktivitet. Helsedirektoratet

Tollosa DN, Tavener M, Hure A, James EL (2019) Adherence to multiple health behaviours in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv 13:327–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00754-0

Hall AE, Boyes AW, Bowman J, Walsh RA, James EL, Girgis A (2012) Young adult cancer survivors’ psychosocial well-being: a cross-sectional study assessing quality of life, unmet needs, and health behaviors. Support Care Cancer 20(6):1333–1341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1221-x

Belanger LJ, Plotnikoff RC, Clark A, Courneya KS (2011) Physical activity and health-related quality of life in young adult cancer survivors: a Canadian provincial survey. J Cancer surviv 5(1):44–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-010-0146-6

Pugh G, Hough R, Gravestock H, Fisher A (2019) The health behaviour status of teenage and young adult cancer patients and survivors in the United Kingdom. Support Care Cancer 28:767–777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04719-y

Warner EL, Nam GE, Zhang Y, McFadden M, Wright J, Spraker-Perlman H, Kinney AY, Oeffinger KC, Kirchhoff AC (2016) Health behaviors, quality of life, and psychosocial health among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancers. J Cancer Surviv 10(2):280–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0474-7

Kaul S, Veeranki SP, Rodriguez AM, Kuo YF (2016) Cigarette smoking, comorbidity, and general health among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer. Cancer 122(18):2895–2905. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30086

Rabin C (2011) Review of health behaviors and their correlates among young adult cancer survivors. J Behav Med 34(1):41–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-010-9285-5

Lie HC, Rueegg CS, Fosså SD, Loge JH, Ruud E, Kiserud CE (2019) Limited evidence of non-response bias despite modest response rate in a nationwide survey of long-term cancer survivors—results from the NOR-CAYACS study. J Cancer Surviv 13:353–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00757-x

Godin G, Jobin J, Bouillon J (1986) Assessment of leisure time exercise behavior by self-report: a concurrent validity study. Can J Public Health 77(5):359–362

World Health Organization (2018) Body mass index - BMI. World Health Organization. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi. Accessed 17 Dec 2018

Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Hveem K, Holmen TL, Midthjell K, Stene TR, Bratberg G, Heggland J, Holmen J (2013) Cohort profile: the HUNT study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol 42(4):968–977. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys095

Lazzeri G, Pammolli A, Azzolini E, Simi R, Meoni V, de Wet DR, Giacchi MV (2013) Association between fruits and vegetables intake and frequency of breakfast and snacks consumption: a cross-sectional study. Nutr J 12(1):123. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-12-123

Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J (1994) Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 47(11):1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34(3):220–233

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16(9):606–613

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T et al (1993) Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res 37(2):147–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-P

LeMasters TJ, Madhavan SS, Sambamoorthi U, Kurian S (2014) Health behaviors among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors: a US population-based case-control study, with comparisons by cancer type and gender. J Cancer Surviv 8(3):336–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-014-0347-5

Glenn BA, Hamilton AS, Nonzee NJ et al. (2018) Obesity, physical activity, and dietary behaviors in an ethnically-diverse sample of cancer survivors with early onset disease. J Psychosoc Oncol:1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2018.1448031

Statisitcs Norway (2019) Røyk, alkohol og andre rusmidler. wwwssbno/royk. Accessed 23 Jan 2019

Hansen B, Anderssen SA, Steene-Johannessen J et al (2015) Fysisk aktivitet og sedat tid blant voksne og eldre i Norge - Nasjonal kartlegging 2014–2015. Helsedirektoratet, Oslo

Totland T, Melnæs BK, Lundberg-Hallén N et al (2012) En landsomfattende kostholdsundersøkelse blant menn og kvinner i Norge i alderen 18–70 år, 2010–11. Helsedirektoratet, Oslo

Spector DJ, Noonan D, Mayer DK, Benecha H, Zimmerman S, Smith SK (2015) Are lifestyle behavioral factors associated with health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of non-Hodgkin lymphoma? Cancer 121(18):3343–3351. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29490

Hess SL, Johannsdottir IM, Hamre H et al (2011) Adult survivors of childhood malignant lymphoma are not aware of their risk of late effects. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden) 50(5):653–659. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186x.2010.550934

Nekhlyudov L, Aziz NM, Lerro C, Virgo KS (2014) Oncologists’ and primary care physicians’ awareness of late and long-term effects of chemotherapy: implications for care of the growing population of survivors. J Oncol Pract 10(2):e29–e36. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2013.001121

Clifford BK, Mizrahi D, Sandler CX, Barry BK, Simar D, Wakefield CE, Goldstein D (2018) Barriers and facilitators of exercise experienced by cancer survivors: a mixed methods systematic review. Support Care Cancer 26(3):685–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3964-5

Bersvendsen HS, Haugnes HS, Fagerli UM et al. (2019) Lifestyle behavior among lymphoma survivors after high-dose therapy with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, assessed by patient-reported outcomes. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden) 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186x.2018.1558370

van Putten M, Husson O, Mols F, Luyer MDP, van de Poll-Franse L, Ezendam NPM (2016) Correlates of physical activity among colorectal cancer survivors: results from the longitudinal population-based profiles registry. Support Care Cancer 24(2):573–583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2816-4

Brunet J, Amireault S, Chaiton M, Sabiston CM (2014) Identification and prediction of physical activity trajectories in women treated for breast cancer. Ann Epidemiol 24(11):837–842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.07.004

Lucia A, Earnest C, Perez M (2003) Cancer-related fatigue: can exercise physiology assist oncologists? Lancet Oncol 4(10):616–625

Nyrop KA, Williams GR, Muss HB, Shachar SS (2016) Weight gain during adjuvant endocrine treatment for early-stage breast cancer: what is the evidence? Breast Cancer Res Treat 158(2):203–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3874-0

Sender L, Zabokrtsky KB (2015) Adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: a milieu of unique features. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 12:465–480. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.92

Reeve BB, Wyrwich KW, Wu AW et al. (2013) ISOQOL recommends minimum standards for patient-reported outcome measures used in patient-centered outcomes and comparative effectiveness research. 22(8):1889–1905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0344-y

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital). This work was supported by The Norwegian Cancer Society under Grant number 45980 and The Research Council of Norway under Grant number 218312.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design, or acquisition of data. Data preparation and analysis were performed by Synne-Kristin Hoffart Bøhn. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Synne-Kristin Hoffart Bøhn, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The NOR-CAYACS study was approved by the South East Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (no: 2015/232), the Norwegian Data Protection Authority (no: 15/00395-2/CGN), the Data Protection Officer at Oslo University Hospital and the CRN. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bøhn, SK.H., Lie, H.C., Reinertsen, K.V. et al. Lifestyle among long-term survivors of cancers in young adulthood. Support Care Cancer 29, 289–300 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05445-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05445-6