Abstract

Background

Recent results of a randomized clinical trial showed that a guided self-help intervention (based on problem-solving therapy) targeting psychological distress among head and neck cancer and lung cancer patients is effective. This study qualitatively explored motivation to start, experiences with and perceived outcomes of this intervention.

Methods

Data were collected from semi-structured interviews of 16 patients. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were analyzed individually by two coders and coded into key issues and themes.

Results

Patients participated in the intervention for intrinsic (e.g. to help oneself) and for extrinsic reasons (e.g. being asked by a care professional or to help improve health care). Participants indicated positive and negative experiences with the intervention. Several participants appreciated participating as being a pleasant way to work on oneself, while others described participating as too confrontational. Some expressed their disappointment as they felt the intervention had brought them nothing or indicated that they felt worse temporarily, but most participants perceived positive outcomes of the intervention (e.g. feeling less distressed and having learned what matters in life).

Conclusions

Cancer patients have various reasons to start a guided self-help intervention. Participants appreciated the guided self-help as intervention to address psychological distress, but there were also concerns. Most participants reported the intervention to be beneficial. The results suggest the need to identify patients who might benefit most from guided self-help targeting psychological distress and that interventions should be further tailored to individual cancer patients’ requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) and lung cancer (LC) patients are often confronted with functional impairments. Many HNC patients have oral dysfunction and speech and swallowing problems. LC patients often have to cope with dyspnea and coughing. Functional impairments can result in psychological distress [1–3], and symptoms of anxiety or depression are highly prevalent in these patients [4, 5]. Previous studies concluded that psychosocial interventions in cancer patients are effective [6, 7]. However, many HNC and LC patients do not use psychosocial interventions [8, 9] due to barriers such as a lack of knowledge about the availability of psychosocial facilities and high costs [6, 9, 10].

Self-help interventions are brief, easily accessible, and low-cost forms of psychosocial support [11, 12]. In primary care, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for depression and anxiety provided as guided self-help can be as effective as face-to-face treatment [12–16].

Results of a recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed that a guided self-help intervention based on the principles of problem-solving therapy (PST) for HNC and LC patients with psychological distress is effective as part of a stepped care (SC) approach compared to usual care [17, 18]. The SC model consisted of watchful waiting (2 weeks), guided self-help (5 weeks) via the Internet or a booklet, face-to-face PST delivered by a nurse, and psychotherapy or medication.

The aims of the present study were to examine cancer patients’ motivation to start a guided self-help intervention, their experiences with the intervention, and the perceived outcomes.

Methods

Context

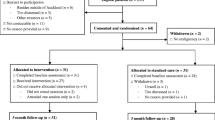

The present study was conducted in the context of the RCT evaluating the efficacy of two guided self-help interventions via the Internet or a booklet: “Headlines” and “Living with lung cancer” as part of SC [17, 18]. In this RCT, 81 patients were randomized into the SC study arm; 54 patients had not recovered after step 1 (watchful waiting) and were offered the guided self-help intervention (step 2). The majority (n = 50, 93 %) wanted to start the intervention, of which 40 % (n = 20) completed the intervention. Participants in the present study were recruited from these 50 patients.

“Headlines” and “Living with lung cancer” are modified versions of an effective brief intervention based on PST [11, 19–22]. The intervention helps participants to regain control over their problems and lives by (1) determining what really matters, (2) focusing only on problems related to what matters, (3) thinking less negatively about problems not related to what is important in life, and (4) accepting important but unsolvable problems. The core of the intervention focuses on solving manageable problems [11, 19, 22]. Information about HNC or LC, cancer treatment, and the potential impact on quality of life is included. The intervention consists of five lessons and takes 5 weeks. Each lesson contains stories from other HNC or LC patients (matching the experience of a patient treated for HNC or LC). Patients are asked to complete assignments focusing on regaining control over their problems and lives. Trained coaches guide the patients. The coaching consisted of brief (10 to 15 min) weekly contacts by e-mail or by telephone and was aimed at providing support in working through the self-help method.

Study participant selection

Participants were eligible for the study if they had started the guided self-help intervention within the previous 18 months. In total, 22 patients were eligible of whom 16 were willing to participate. The remaining patients did not want to participate (n = 1) or could not be reached (n = 5). All participants provided written informed consent. See Table 1 for the participants’ characteristics.

Procedure and interview structure

Interviews were performed by one interviewer (HM) and scheduled at the participant’s preferred location. The semi-structured interview schedule consisted of three main topics (motivation, experiences, and perceived outcomes) with corresponding questions (Table 2). The interview topics and questions were derived from our clinical experience and the literature [19, 22]. The interviews lasted between 35 and 99 min (median 63.5 min) and were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed independently by two coders (AK and HM) using thematic analysis [23]. Both coders read all transcripts separately several times to familiarize themselves with the data. Quotes relating to the three main topics were independently selected and coded into key issues and themes. Findings were discussed after every three coded transcripts, and differences were resolved until consensus was reached. The coders created a coding framework, which was revised if necessary following consensus meetings. In case of disagreement, a third coder (CvU) was consulted.

One coder (AK) examined the raw data again to ensure the robustness of the analytical process and to confirm that all data were reflected in the coding. Quotes provided in this article were translated from Dutch into English. To ensure anonymity, all identifying information was removed.

Results

Motivation to start

Participants had both intrinsic and extrinsic reasons to start the intervention (Table 3). One intrinsic reason was self-help. Participants assumed that participating would make them feel happier. Furthermore, participants expected to regain a grip on their lives after partaking:

“Cancer is kind of a life sentence, but I do not want it to rule my entire life; it has done enough of that, and I am being offered the chance of a bit of life and I want to have a grip on it myself.”

Several participants mentioned that they decided to start out of curiosity: the intervention seemed interesting and they expected to learn something. Also, some anticipated that they could save time and money compared to regular care. Others started for less clear reasons, such as “It can’t hurt to try”.

Most reported reasons to start were extrinsic: being asked to participate by a care professional or to help others. Practically, all wanted to participate to help science or to improve health care. Giving something in return for being treated well was also mentioned.

Not all participants were immediately convinced, and some considered not taking part initially. Nevertheless, they decided to start, mainly for extrinsic reasons.

Experiences

In general, both positive experiences—“pleasant”, “clarifying”, and “supportive”—and negative experiences—“exhausting” or “confronting”—were expressed in terms of the intervention (Table 4).

Experiences with assignments

Several participants indicated that writing down their thoughts on what matters in life as well as their problems was a pleasant way to work on oneself. They especially appreciated the fact that the assignments could be re-read later in time:

“Yes, and I can also read it again. It helps you along quite a bit (…) You can then log on again and read back what you said before. Slowly I could start to make my own lists of what is important (…) This is what you thought at that time, here’s what you think now: it is good, leave it. Here is the focus, here is what you should think about.”

In contrast, just as many participants indicated that writing this down was confronting and upsetting:

“And then you are also faced with this block, you know, I sit there with that pen hovering over that piece of paper and (…) then I throw in the towel. It’s like me not wanting to know the type of cancer. I think: I simply can’t handle it – because then I would, you know, become aware of certain cases where they end. (…) And if you get something similar, you have to open up, open all the boxes, which I don’t want to do.”

Some mentioned that the intervention was too complicated: assignments were unclear, and finding the right words was difficult. Participants experienced the assignments as containing too much repetition, too many forms, or too little room to share their own story. Others found they lacked the self-discipline to complete the assignments or that completing was considered as not rewarding.

Experiences with coaching

Most participants valued the coach and indicated that the coach was understanding and monitored their wellbeing. Participants also felt safe to share shameful thoughts and experiences. Participants stated that the personal contact was crucial and indispensable. The coach encouraged them to complete the intervention and served as a source of motivation:

“Well, yes, because you talk to someone on the phone. They ring you. So that is, of course, even more motivation to do it – to do those worksheets and to, to properly think about things and try to change them. I mean, you are supposed to be able to tell something when someone calls, aren’t you? So, to me it was an incentive to do my very best, so to speak.”

All participants indicated that the feedback provided was short. Some found the feedback powerful and educational. Others evaluated it as being shallow, not helpful, serving only as proof that the assignments had been read, or described the feedback as patronizing:

“Oh, she says: Yes, you have answered the assignments correctly, you are making a good effort. And I thought: come on, you must be joking, I am not a toddler.”

Several participants remarked that the coach did not give any advice despite their need:

“(…) yes, I do think so, and I thought, like: yes, he is only calling to discuss it. You don’t get, ehm, like: you had better do this or better do that… No. I somehow missed that.”

Experiences with the cancer-specific format

Some participants experienced the cancer-related stories of others as recognizable and realistic. Others mentioned that the stories made them put their own situation into perspective. A couple said that they found it interesting to read about a more severe case than their own:

“No, I liked to read all of those. I wasn’t necessarily looking for people with the same experience I had. But it was also nice to see, to say: oh, I don’t have that (…) That is one up for me.”

Several participants appreciated the cancer-specific format, because they believed that psychological distress caused by cancer is different:

“Because this fear of death is completely different from other stress in life. That is what it is all about, the fear of death – and not just death, but a long, nasty and painful death from cancer.”

However, others stated that the stories were too severe or distracted them from their own situation. Some noted that it was difficult to be confronted with the negative sides of the disease in the cancer-related stories.

Experiences with the home setting and time investment

The ability to follow the course at home was viewed as a positive experience by almost all:

“At home you are in your familiar surroundings. Perhaps that makes you talk more freely, because everything around you is familiar. If you have to go to a psychiatrist, you might be nervous – and don’t really know what to say exactly.”

The home setting could also lead to less time investment compared to seeing a therapist. In addition, several expressed that they could follow the course at their own pace and that the homework forms were filled out quickly. Others felt that the intervention took up too much time. Finally, a couple of participants remarked that they had experienced the intervention as too short to be able to achieve a significant psychological change:

“You can say to people, like, you have to think this or that. But really, it is just like walking: It takes months for people to be brainwashed.”

Adherence

All seven participants who adhered to the intervention indicated that they finished the intervention because of their attitude that you should finish something you have started.

The nine participants who did not adhere mentioned several reasons. Some preferred to manage their problems by themselves or felt adequately supported by someone else (spouse, physiotherapist). Others mentioned that they did not perceive any benefit or evaluated the intervention as too confrontational or distressing:

“By the time of the next class you can do the same, really, and then you have to indicate whatever has changed. Well, nothing had changed for me. It is… I felt the same from the start, really, so it only reinforced my feeling of, well, this is useless.”

Several participants indicated that they felt too worried to be able to focus on the intervention or preferred talking with a professional.

Perceived outcomes

Participants perceived various outcomes (Table 5).

Positive psychological changes

Several participants indicated to have learned to structure their feelings and thoughts through participating:

“I was made wiser, how important it was to focus on my thoughts in a structured way. I have also changed that, I am still trying to do so.”

Others explained that they learned how to put things into perspective. Several mentioned that they now realized that what happens in daily life could be viewed from other perspectives:

“Well, if someone is for instance (…) rude to you. Then I always thought, like: oh, I knew it, she doesn’t like me. But then, you can also look at it in another way, like: oh, she must be busy.”

A couple indicated that participation helped to stop ruminating. They explained that specifically the ability to re-read the completed assignments supported them in doing so.

In addition, they learned that looking for distraction helps to stop worrying:

“If I feel very down about something, so last week too, then I also had it (…). I then called the hairdresser’s and made an appointment with the hairdresser.”

Participants also learned to point out what is most important in their lives by setting priorities: focus on what is important in life (“spouse”, “kids”, “having fun”), and drop what is less important (“doing chores”, “being liked by others”).

Some indicated that they had learned to accept unchangeable problems. Some mentioned that their self-knowledge and self-reflection had improved:

“Well, better insight in myself, think about myself, and yet see things in a different perspective.”

Others stated that partaking in the intervention led to a “confirmation of self-insight”.

Several indicated that their openness or attitude towards other people had improved:

“That you do not keep everything to yourself after all, become a bit more open towards your family, but that you do not burden anyone with it, just try to find a golden mean.”

Finally participants indicated they managed to take up the threads of life after cancer.

Less psychological distress

Most participants stated that they had more peace of mind:

“Here is the focus, this is what you must think about. That also helped me, because I just do so once in a while and then leave it. Not always fret, fret, fret. That is really exhausting.”

No positive psychological changes

Others did not perceive any positive outcomes. A few participants declared that they already had sufficient coping strategies. They explained for example that the intervention did not bring them anything or that they perceived partaking as a disappointment because the intervention only led to a “confirmation of self-insight”:

“I know myself in that respect extremely well, that this doesn’t help me, because I already am such a reflective person; because I already write down everything I feel and think, of pain and gloom. I am a bit of therapeutic myself (…) Plus I have considerable self-knowledge.”

Some participants expressed that they did not learn how to deal with unchangeable problems, e.g. fear of recurrence of cancer:

“No, not really, for things that do not tally and are not changeable, I worry about those.”

In addition, several declared they appreciated they could express negative feelings during the intervention, but that these feelings were not removed:

“Well, I did enjoy participating, for at that moment you can share your feelings for a few moments. But, well, see, you can’t make it disappear.”

(Increased) Psychological distress

Several participants expressed that they still felt helpless or (temporarily) felt worse as an outcome of participation. For those participants who indicated to feel worse, this was often a reason to end participation:

“Yes, for I am haunted by it. Ehm, yes, it stayed with me for a while, a few days (…) that was worse for me and then I thought, I have to quit.”

Discussion

This study investigated the experiences and outcomes of a guided self-help intervention targeting psychological distress among HNC and LC patients and their motivation to start the intervention.

Understanding the motivation to participate is important, as it may influence outcomes [24, 25]. This study showed that many HNC and LC survivors started the intervention for extrinsic reasons. Altruism is common among cancer patients who participate in research [26–28]. However, there were also patients who started the intervention for intrinsic reasons.

In our trial on stepped care, only 7 % of patients who had not recovered after a period of watchful waiting declined the guided self-help intervention. This percentage is much better compared to the 71 % that declined help in a study by Clover et al. [29], exploring reasons for declining help among cancer patients with significant emotional distress. The most common reason for declining help in that study was “I prefer to manage myself”. This underscores that guided self-help is welcomed by cancer patients.

Participants recalled positive and negative experiences. Writing down thoughts and what matters in life and being able to re-read the assignments were experienced as pleasant by several participants. This is in line with results from Beattie et al. [30], regarding experiences with online CBT for depression in primary care. They concluded that online CBT was more attractive to patients who felt comfortable communicating their feelings in writing and enjoyed to review what was written down.

The cancer-related stories were experienced as either recognizable and pleasurable or as distressing. Previous studies have shown that individual differences in self-reported health status, sensitivity to social comparison information, and neuroticism determine how cancer patients react to stories of other cancer patients and whether they benefit from it or not [31–33]. These findings are important to take into account to tailor the cancer-specific format of the guided self-help intervention in the future.

Ly et al. [34] found that coaching was depicted as an essential component of a smartphone-based treatment for depression in primary care. Also, Gerhards et al. [35] found that participants believed guidance would improve adherence. These perceived advantages of guidance have been confirmed in several reviews and meta-analyses, revealing that internet-based interventions with guidance are more effective and lead to greater adherence [15, 16, 36–39].

Similar to our findings, Donkin et al. [40] found in their study examining motivators to persist with online interventions that completers indicated they had finished the intervention because of their sense of duty and commitment. Furthermore, the perception of receiving a benefit from the program was a reason to persist, as well as feeling in control by e.g. being able to set the pace. A motivational interview prior to start of the intervention, individual tailoring [35], and increasing dialog support through reminders is suggested to improve adherence [37, 41, 42].

By exploring participants’ perceived outcomes, we gained insight in how they believed they were affected by partaking. Some perceived positive outcomes, while others perceived no positive psychological changes or remained distressed. Several participants stated to have learned what matters in life, to be able to put things in perspective, and indicated that they had taken up the threads of life. These perceived outcomes can be summarized as achieving an “enhanced internal locus of control”. The achievement of feeling in control is aimed for by “Headlines” and “Living with lung cancer”, since this is one of the protective factors against the development of symptoms of anxiety or depression [19]. Additionally, participants noticed to be more open to friends and family and to have more self-knowledge.

Negative outcomes were also identified in this study. The negatively perceived outcomes imply that a guided self-help intervention may have harmful consequences for some participants. Future research should disentangle which patients benefit from guided self-help interventions.

A limitation of the study was that interviews were conducted after participants had completed the intervention, and follow-up measures had been conducted. Consequently, the elapsed time since starting the intervention varied. Participants who had more recently started the intervention may have had a more detailed recollection of their experience. Also, the experiences and outcomes obtained were linked to the current intervention and may not be applicable to other self-help interventions for cancer patients.

From a clinical point of view, it can be concluded that the guided self-help intervention is perceived as beneficial but may be improved by incorporating a motivational interview prior to start and by tailoring the intervention to patients’ individual needs.

Conclusion

Cancer patients had various reasons to start a guided self-help intervention. They appreciated the intervention in terms of recovering from psychological distress, yet there were also concerns in the way participants experienced the intervention. Although most reported the intervention as beneficial, not all participants perceived improved outcomes. These results suggest the need to identify patients who might benefit most from guided self-help targeting psychological distress.

References

Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Eerenstein SE, Van der Linden MH, Kuik DJ, de Bree R, Leemans CR (2007) Distress in spouses and patients after treatment for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 117(2):238–241. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000250169.10241.58

de Graeff A, de Leeuw JR, Ros WJ, Hordijk GJ, Blijham GH, Winnubst JA (2000) Long-term quality of life of patients with head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 110(1):98–106. doi:10.1097/00005537-200001000-00018

Pozo CL, Morgan MA, Gray JE (2014) Survivorship issues for patients with lung cancer. Cancer Control 21(1):40–50

Krebber AM, Buffart LM, Kleijn G, Riepma IC, de Bree R, Leemans CR, Becker A, Brug J, van Straten A, Cuijpers P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2014) Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psycho-Oncology 23(2):121–130. doi:10.1002/pon.3409

Buchmann L, Conlee J, Hunt J, Agarwal J, White S (2013) Psychosocial distress is prevalent in head and neck cancer patients. Laryngoscope 123(6):1424–1429. doi:10.1002/lary.23886

Carlson LE, Bultz BD (2004) Efficacy and medical cost offset of psychosocial interventions in cancer care: making the case for economic analyses. Psycho-Oncology 13(12):837–849. doi:10.1002/pon.832. discussion 850-56

Hart SL, Hoyt MA, Diefenbach M, Anderson DR, Kilbourn KM, Craft LL, Steel JL, Cuijpers P, Mohr DC, Berendsen M, Spring B, Stanton AL (2012) Meta-analysis of efficacy of interventions for elevated depressive symptoms in adults diagnosed with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 104(13):990–1004. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs256

Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, Goodey E, Koopmans J, Lamont L, MacRae JH, Martin M, Pelletier G, Robinson J, Simpson JS, Speca M, Tillotson L, Bultz BD (2004) High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 90(12):2297–2304. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887

Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, de Bree R, Keizer AL, Houffelaar T, Cuijpers P, van der Linden MH, Leemans CR (2009) Computerized prospective screening for high levels of emotional distress in head and neck cancer patients and referral rate to psychosocial care. Oral Oncol 45(10):e129–e133. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.01.012

Andersen BL, DeRubeis RJ, Berman BS, Gruman J, Champion VL, Massie MJ, Holland JC, Partridge AH, Bak K, Somerfield MR, Rowland JH, American Society of Clinical O (2014) Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: an American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 32(15):1605–1619. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611

van Straten A, Cuijpers P, Smits N (2008) Effectiveness of a web-based self-help intervention for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 10(1):e7. doi:10.2196/jmir.954

Cuijpers P, Donker T, van Straten A, Li J, Andersson G (2010) Is guided self-help as effective as face-to-face psychotherapy for depression and anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Psychol Med 40(12):1943–1957. doi:10.1017/S0033291710000772

Seekles W, van Straten A, Beekman A, van Marwijk H, Cuijpers P (2011) Effectiveness of guided self-help for depression and anxiety disorders in primary care: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res 187(1–2):113–120. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2010.11.015

Lewis C, Pearce J, Bisson JI (2012) Efficacy, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of self-help interventions for anxiety disorders: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci 200(1):15–21. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084756

Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklicek I, Riper H, Keyzer J, Pop V (2007) Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 37(3):319–328. doi:10.1017/S0033291706008944

Griffiths KM, Farrer L, Christensen H (2010) The efficacy of internet interventions for depression and anxiety disorders: a review of randomised controlled trials. Med J Aust 192(11 Suppl):S4–11

Krebber AM, Leemans CR, de Bree R, van Straten A, Smit F, Smit EF, Becker A, Eeckhout GM, Beekman AT, Cuijpers P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2012) Stepped care targeting psychological distress in head and neck and lung cancer patients: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Cancer 12:173. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-12-173

Krebber AM, Jansen F, Witte BI, Cuijpers P, de Bree R, Becker-Commissaris A, Smit EF, van Straten A, Eeckhout AM, Beekman AT, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2016) Stepped care targeting psychological distress in head and neck cancer and lung cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Oncol. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdw230

Bowman D (1995) Self-examination therapy: treatment for anxiety and depression. In: VandeCreek L (ed) Innovations in clinical practice: a source book. Professional Resource Press/Professional Resource Exchange, Sarasota

Bowman D, Scogin F, Lyrene B (1995) The efficacy of self-examination therapy and cognitive bibliotherapy in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. Psychother Res 5(2):131–140

Bowman D, Scogin F, Floyd M, Patton E, Gist L (1997) Efficacy of self-examination therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Couns Psychol 44:267–273

Mynors-Wallis L (2005) Problem solving treatment for anxiety and depression: a practical guide. Oxford University Press, New York

Braun V, Clarke V (2012) Thematic analysis. In: Cooper H, Camic PM, Long DL, Panter AT, Rindskopf D, Sher KJ (eds) APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 57–71

Rosenbaum JR, Wells CK, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, Kernan WN, Horwitz RI (2005) Altruism as a reason for participation in clinical trials was independently associated with adherence. J Clin Epidemiol 58(11):1109–1114. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.03.014

Seelig BJ, Dobelle WH (2001) Altruism and the volunteer: psychological benefits from participating as a research subject. ASAIO J 47(1):3–5

Moorcraft SY, Marriott C, Peckitt C, Cunningham D, Chau I, Starling N, Watkins D, Rao S (2016) Patients’ willingness to participate in clinical trials and their views on aspects of cancer research: results of a prospective patient survey. Trials 17(1):17. doi:10.1186/s13063-015-1105-3

Dhalla S, Poole G (2013) Motivators to participation in medical trials: the application of social and personal categorization. Psychol Health Med 18(6):664–675. doi:10.1080/13548506.2013.764604

Jenkins V, Fallowfield L (2000) Reasons for accepting or declining to participate in randomized clinical trials for cancer therapy. Br J Cancer 82(11):1783–1788. doi:10.1054/bjoc.2000.1142

Clover KA, Mitchell AJ, Britton B, Carter G (2015) Why do oncology outpatients who report emotional distress decline help? Psycho-Oncology 24(7):812–818. doi:10.1002/pon.3729

Beattie A, Shaw A, Kaur S, Kessler D (2009) Primary-care patients’ expectations and experiences of online cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: a qualitative study. Health Expect 12(1):45–59. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00531.x

Brakel TM, Dijkstra A, Buunk AP (2012) Effects of the source of social comparison information on former cancer patients’ quality of life. Br J Health Psychol 17(4):667–681. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02064.x

Brakel TM, Dijkstra A, Buunk AP, Siero FW (2012) Impact of social comparison on cancer survivors’ quality of life: an experimental field study. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association 31(5):660–670. doi:10.1037/a0026572

Buunk AP, Brakel TM, Bennenbroek FC, Stiegelis HE, Sanderman R, Van Den Bergh AM, Hagedoorn M (2009) Neuroticism and responses to social comparison among cancer patients. Eur J Pers 23(6):475–487. doi:10.1002/per.720

Ly KH, Janni E, Wrede R, Sedem M, Donker T, Carlbring P, Andersson G (2015) Experiences of a guided smartphone-based behavioral activation therapy for depression: a qualitative study. Internet Interventions 2:60–68

Gerhards SA, Abma TA, Arntz A, de Graaf LE, Evers SM, Huibers MJ, Widdershoven GA (2011) Improving adherence and effectiveness of computerised cognitive behavioural therapy without support for depression: a qualitative study on patient experiences. J Affect Disord 129(1–3):117–125. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.012

Newman MG, Szkodny LE, Llera SJ, Przeworski A (2011) A review of technology-assisted self-help and minimal contact therapies for anxiety and depression: is human contact necessary for therapeutic efficacy? Clin Psychol Rev 31(1):89–103. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.008

Kelders SM, Kok RN, Ossebaard HC, Van Gemert-Pijnen JE (2012) Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J Med Internet Res 14(6):e152. doi:10.2196/jmir.2104

Richards D, Richardson T (2012) Computer-based psychological treatments for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 32(4):329–342. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.004

Johansson R, Andersson G (2012) Internet-based psychological treatments for depression. Expert Rev Neurother 12(7):861–869. doi:10.1586/ern.12.63. quiz 870

Donkin L, Glozier N (2012) Motivators and motivations to persist with online psychological interventions: a qualitative study of treatment completers. J Med Internet Res 14(3):e91. doi:10.2196/jmir.2100

Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S (2010) Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res 12(1):e4. doi:10.2196/jmir.1376

Fry JP, Neff RA (2009) Periodic prompts and reminders in health promotion and health behavior interventions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 11(2):e16. doi:10.2196/jmir.1138

Acknowledgments

The study is funded by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, grant number 300020012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Krebber, AM.H., van Uden-Kraan, C.F., Melissant, H.C. et al. A guided self-help intervention targeting psychological distress among head and neck cancer and lung cancer patients: motivation to start, experiences and perceived outcomes. Support Care Cancer 25, 127–135 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3393-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3393-x