Abstract

Purposes

Patient Generated Index (PGI) is designed to both ask and document quality of life (QOL) concerns. Its validity with respect to standard QOL measures has not been fully established for advanced cancer when QOL concerns predominate. The specific objective of this study is to identify, for people with advanced cancer, similarities and differences in ratings of global QOL between personalized and standard measures.

Methods

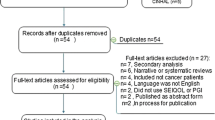

A total of 192 patients completed five QOL measures at study entry: PGI, generic measures (SF-6D, EQ-5D), and cancer-specific measures of QOL (McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire and Edmonton Symptoms Assessment Scale). Comparisons among total scores were compared using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE).

Results

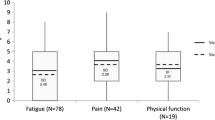

Patients voiced 114 areas of QOL concerns by the PGI with the top three being fatigue, sleep, and pain (39.2, 22.6, and 21.6 %, respectively). PGI total QOL score was 25 to 30 percentage points lower than those documented by the other measures, particularly when QOL was poor. Correlations between PGI and other measures were low.

Conclusion

PGI allowed patients to express a wide range of QOL concerns, many that were not assessed by other QOL measures. If only one QOL measure is to be included, either in a clinical setting or for research, the PGI would satisfy many of the criteria for “best choice.” PGI could be considered a cancer-specific QOL measure.

Implications for cancer

This study provides evidence that the PGI would be a good measure for patients and clinicians to use together to identify areas of concern that require attention and monitor changing needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

WCRF International (2015) Cancer worldwide data. [cited 5/3]; Available from: http://www.wcrf.org/int/cancer-facts-figures/worldwide-data

de Boer AG et al (2008) Work ability and return-to-work in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 98(8):1342–1347

Hoffman B (2005) Cancer survivors at work: a generation of progress. CA Cancer J Clin 55:271–280

Lehmann JF et al (1978) Cancer rehabilitation: assessment of need, development, and evaluation of a model of care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 59(9):410–419

Ness KK et al (2006) Physical performance limitations and participation restrictions among cancer survivors: a population-based study. Ann Epidemiol 16(3):197–205

O’Boyle CA et al (1992) Individual quality of life in patients undergoing hip replacement. Lancet 339(8801):1088–1091

Ruta DA et al (1994) A new approach to the measurement of quality of life. The Patient-Generated Index. Med Care 32(11):1109–1126

Broadhead JK, Robinson JW, Atkinson MJ (1998) A new quality-of-life measure for oncology: The SEIQoL. J Psychosoc Oncol 16(1):21–35

Tavernier SS et al (2011) Validity of the Patient Generated Index as a quality-of-life measure in radiation oncology. Oncol Nurs Forum 38(3):319–329

Tavernier SS, Totten AM, Beck SL (2011) Assessing content validity of the patient generated index using cognitive interviews. Qual Health Res 21(12):1729–1738

Frick E, Tyroller M, Panzer M (2007) Anxiety, depression and quality of life of cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy: a cross-sectional study in a community hospital outpatient centre. Eur J Cancer Care 16(2):130–136

Montgomery C et al (2002) Individual quality of life in patients with leukaemia and lymphoma. Psychooncology 11(3):239–243

Waldron D et al (1999) Quality-of-life measurement in advanced cancer: assessing the individual. J Clin Oncol 17(11):3603–3611

Rodriguez AM, Mayo NE, Gagnon B (2013) Independent contributors to overall quality of life in people with advanced cancer. Br J Cancer 108(9):1790–1800

Cohen SR et al (1997) Validity of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire in the palliative care setting: a multi-centre Canadian study demonstrating the importance of the existential domain. Palliat Med 11(1):3–20

Osoba D, King M (2005) Meaningful differences. In: Fayers PM, Hays RD (eds) Assessing quality of life in clinical trials, 2 edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 243–257 p. 5 A.D. 251

Wilson IB, Cleary PD (1995) Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 273(1):59–65

Ruta DA, Garratt AM, Russell IT (1999) Patient centred assessment of quality of life for patients with four common conditions. Qual Health Care 8(1):22–29

Camilleri-Brennan J, Ruta DA, Steele RJ (2002) Patient generated index: new instrument for measuring quality of life in patients with rectal cancer. World J Surg 26(11):1354–1359

Lewis S et al (2002) Quality of life issues identified by palliative care clients using two tools. Contemp Nurse 12(1):31–41

Llewellyn CD, McGurk M, Weinman J (2006) Head and neck cancer: to what extent can psychological factors explain differences between health-related quality of life and individual quality of life? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 44(5):351–357

Calman KC (1984) Quality of life in cancer patients—an hypothesis. J Med Ethics 10(3):124–127

EuroQOL Group (1990) EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 16(3):199–208

Gudex C et al. (1996) Health state valuations from the general public using the visual analogue scale. Qual Life Res 5(6):521–531

Dolan P (1997) Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 35(11):1095–1108

Bansback N et al (2012) Canadian valuation of EQ-5D health states: preliminary value set and considerations for future valuation studies. PLoS One 7(2):e31115

Oremus M et al (2014) Health utility scores in Alzheimer’s disease: differences based on calculation with American and Canadian preference weights. Value Health 17(1):77–83

Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ (2005) US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care 43(3):203–220

Lee JA et al (2014) Comparison of health-related quality of life between cancer survivors treated in designated cancer centers and the general public in Korea. Jpn J Clin Oncol 44(2):141–152

Shim EJ et al (2011) Comprehensive needs assessment tool in cancer (CNAT): the development and validation. Support Care Cancer 19(12):1957–1968

Glick HA et al (1998) Empirical criteria for the selection of quality-of-life instruments for the evaluation of peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 14(3):419–430

Pickard AS et al (2007) Health utilities using the EQ-5D in studies of cancer. PharmacoEconomics 25(5):365–384

Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M (2002) The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ 21(2):271–292

Hever, N.V., et al (2014) Health related quality of life in patients with bladder cancer: a cross-sectional survey and validation study of the Hungarian version of the bladder cancer index. Pathol Oncol Res

Gallop K et al (2015) A qualitative evaluation of the validity of published health utilities and generic health utility measures for capturing health-related quality of life (HRQL) impact of differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) at different treatment phases. Qual Life Res 24(2):325–338

Teckle P et al (2013) Mapping the FACT-G cancer-specific quality of life instrument to the EQ-5D and SF-6D. Health Qual Life Outcomes 11:203

Lee L et al (2013) Valuing postoperative recovery: validation of the SF-6D health-state utility. J Surg Res 184(1):108–114

Barton GR et al (2008) An assessment of the discriminative ability of the EQ-5D index, SF-6D, and EQ VAS, using sociodemographic factors and clinical conditions. Eur J Health Econ 9(3):237–249

Hornbrook MC et al (2011) Complications among colorectal cancer survivors: SF-6D preference-weighted quality of life scores. Med Care 49(3):321–326

Bruera E et al (1991) The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 7(2):6–9

Cohen SR et al (2001) Changes in quality of life following admission to palliative care units. Palliat Med 15(5):363–371

Cohen SR, Mount BM (2000) Living with cancer: “good” days and “bad” days—what produces them? Can the McGill quality of life questionnaire distinguish between them? Cancer 89(8):1854–1865

Cohen SR et al (1995) The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: a measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease. A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med 9(3):207–219

Cohen SR et al (1996) Existential well-being is an important determinant of quality of life. Evidence from the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire. Cancer 77(3):576–586

Nekolaichuk CL et al (1999) Assessing the reliability of patient, nurse, and family caregiver symptom ratings in hospitalized advanced cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 17(11):3621–3630

Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M (2000) Validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale. Cancer 88(9):2164–2171

Cohen SR et al (1996) Quality of life in HIV disease as measured by the McGill quality of life questionnaire. AIDS 10(12):1421–1427

Glare PA et al (2014) Pain in cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 32(16):1739–1747

Denlinger CS et al (2014) Survivorship: sleep disorders, version 1.2014. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 12(5):630–642

Dickerson SS et al (2014) Sleep-wake disturbances in cancer patients: narrative review of literature focusing on improving quality of life outcomes. Nat Sci Sleep 6:85–100

Moens K, Higginson IJ, Harding R (2014) Are there differences in the prevalence of palliative care-related problems in people living with advanced cancer and eight non-cancer conditions? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag 48(4):660–677

Olson K (2014) Sleep-related disturbances among adolescents with cancer: a systematic review. Sleep Med 15(5):496–501

Otte JL et al (2015) Systematic review of sleep disorders in cancer patients: can the prevalence of sleep disorders be ascertained? Cancer Med 4(2):183–200

Aaronson NK et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85(5):365–376

Letellier, M.E., D. Dawes, and N. Mayo (2014) Content verification of the EORTC QLQ-C30/EORTC QLQ-BR23 with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Qual Life Res

Cella DF et al (1993) The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11(3):570–579

Dolan P (1999) Whose preferences count? Med Decis Mak 19(4):482–486

Kuspinar A, Mayo NE (2013) Do generic utility measures capture what is important to the quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis? Health Qual Life Outcomes 11:71

Garratt A et al (2002) Quality of life measurement: bibliographic study of patient assessed health outcome measures. BMJ 324(7351):1417

Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW (2003) Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 41(5):582–592

McHorney CA, Tarlov AR (1995) Individual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res 4(4):293–307

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Statement of informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aburub, A.S., Gagnon, B., Rodríguez, A.M. et al. Using a personalized measure (Patient Generated Index (PGI)) to identify what matters to people with cancer. Support Care Cancer 24, 437–445 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2821-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2821-7