Abstract

Objective

Integrative oncology incorporates complementary medicine (CM) therapies in patients with cancer. We explored the impact of an integrative oncology therapeutic regimen on quality-of-life (QOL) outcomes in women with gynecological cancer undergoing chemotherapy.

Patients and methods

A prospective preference study examined patients referred by oncology health care practitioners (HCPs) to an integrative physician (IP) consultation and CM treatments. QOL and chemotherapy-related toxicities were evaluated using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) and Measure Yourself Concerns and Wellbeing (MYCAW) questionnaire, at baseline and at a 6–12-week follow-up assessment. Adherence to the integrative care (AIC) program was defined as ≥4 CM treatments, with ≤30 days between each session.

Results

Of 128 patients referred by their HCP, 102 underwent IP consultation and subsequent CM treatments. The main concerns expressed by patients were fatigue (79.8 %), gastrointestinal symptoms (64.6 %), pain and neuropathy (54.5 %), and emotional distress (45.5 %). Patients in both AIC (n = 68) and non-AIC (n = 28) groups shared similar demographic, treatment, and cancer-related characteristics. ESAS fatigue scores improved by a mean of 1.97 points in the AIC group on a scale of 0–10 and worsened by a mean of 0.27 points in the non-AIC group (p = 0.033). In the AIC group, MYCAW scores improved significantly (p < 0.0001) for each of the leading concerns as well as for well-being, a finding which was not apparent in the non-AIC group.

Conclusions

An IP-guided CM treatment regimen provided to patients with gynecological cancer during chemotherapy may reduce cancer-related fatigue and improve other QOL outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The integration of complementary medicine (CM) within supportive cancer care has become a hallmark of a transition in the conventional health care paradigm. The emergence of the “integrative oncology” concept is based on three-core axis: patients’ motivation for CM use, to be provided within their treating oncology center, emerging evidence-based clinical research findings regarding a number of various CM interventions in improving quality-of-life (QOL)-related outcomes, and an increasing awareness among oncologists to the widespread use of CM by their patients, with potentially negative effects [1].

Integrative oncology care takes place under the supervision and guidance of integrative physicians (IPs) who have extensive training in both CM and supportive cancer care [2, 3]. In many cases, patients are referred by their oncology health care practitioner (HCP) to an IP for consultation on CM use, from which an HCP-IP dialogue ensues. Integrative oncology treatments are tailored to patients’ concerns, with the ultimate goal of improving patients’ QOL and well-being. A number of integrative oncology models have been described for the general oncology setting [1]. To the best of our knowledge, no study has described an integrative model for gynecologic oncology which focuses on supportive care during chemotherapy treatments provided within a conventional setting. CM use among patients with gynecologic cancers is prevalent, with between one and two thirds of patients reporting the use of these modalities [4, 5]. The absence of a research model is surprising, since gynecologic oncologists have been found to have a more “open-minded” attitude toward CM when compared with other oncology professionals [6].

The rationale for integrating an IP-administered CM consultation within gynecologic oncology care includes the large body of evidence regarding the potential beneficial role of CM in improving patients’ QOL [7–14]. At the same time, the use of CM has potential risks, such as the possibility of interactions between dietary supplements and chemotherapy. Such interactions may result in a decreased (e.g., Ginkgo biloba and paclitaxel) [15] or increased effect (e.g., curcumin with paclitaxel) [16] of the chemotherapy agent.

In the present study, we explored the impact of an IP-managed integrative oncology model on QOL-related outcomes in gynecologic oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy. The effects of the integrative oncology therapeutic process on the IP-HCP dialogue were examined as well, as well as the barriers which limited the implementation of the integrative model.

Methods

Study design and location

The study was designed as a prospective registry protocol-based preference study, evaluating the impact of an integrative CM intervention on patients’ concerns and well-being, including symptoms induced by chemotherapy. Eligible participants were patients diagnosed with gynecological cancer aged ≥18 years who were undergoing chemotherapy at an oncology referral center in northern Israel, between July 2009 and May 2014.

Integrative gynecologic oncology model

The Integrative Gynecologic Oncology Program (IGOP) was launched in 2008 by the Clalit Health Care Service in northern Israel. This community-based service provides chemotherapy in a day-care setting, within a conventional oncology clinic. Hospital-based surgical treatments are provided, as well as in-patient treatments of chemotherapy-induced toxicities and palliative care. The IGOP was established with three main goals, the first of which was the assessment of patients’ concerns, symptoms, and QOL-related issues, based on individual and group interviews with the patients, HCPs, and CM practitioners [17]. The second goal of the program was to promote an understanding of patients’ expectations from the IP consultation and involvement of their oncology HCPs in the referral and design of the integrative therapy plan [18]. And finally, the third goal of the IGOP was to conduct weekly meetings with the gynecologic oncology team, during which the findings of up-to-date clinical research on CM treatments for QOL-related outcomes in gynecologic-oncology were presented. The presentations were followed by a discussion whose purpose was to identify patients’ unmet concerns regarding outcomes such as cancer-related fatigue and to address the effect of toxicities on chemotherapy dose density restriction (e.g., chemotherapy-induced neuropathy).

Referring HCPs included gynecological-oncologists, oncologists, nurse oncologists, and psycho-oncologists. The HCPs were asked to refer their patients to the IP consultation using a structured format in which specific, QOL-related indications were cited. These included cancer-related fatigue, gastrointestinal toxicities (e.g., mouth sores, nausea, appetite change, and constipation), pain, chemotherapy-induced neuropathy and hematological toxicities (e.g., neutropenia), emotional and spiritual distress, dyspnea, insomnia, and others. Referring HCPs were also able to provide the indication for referral in a free-text format. The goal of the weekly meetings between IPs and gynecological oncology HCPs was the ongoing assessment of the CM therapeutic program. Emphasis was placed during these interactions on those patients with challenging QOL-related issues, with recommendations based on up-to-date research findings on the effectiveness and safety of the CM modalities. Following these meetings, CM treatment modifications were made and reassessed at the next meeting the following week.

Assessment of patients’ concerns and QOL

The IP consultation entails an hour-long discussion between patients and IPs who are medical doctors trained in CM treatment modalities and supportive cancer care. A follow-up IP visit is scheduled at between 6 and 12 weeks following the initial consultation. Treatment-related symptoms and QOL-related outcomes are assessed at both the initial and follow-up IP visits, using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) study and the Measure Yourself Concerns and Wellbeing (MYCAW) questionnaire [19, 20]. The ESAS is composed of a list of ten symptoms (pain, fatigue nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, shortness of breath, appetite, sleep, and feeling of well-being) and symptom severity self-scored by patients, with scores ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 10 (worst possible severity). In MYCAW tool, respondents are asked to complete a Likert-like questionnaire regarding their two most important concerns, scored from 0 (of no concern) to 6 (of greatest concern). In addition to addressing their symptoms, patients are asked to score their general feeling of well-being (0—as good as it could be; 6—as bad as it could be), followed by two open-ended questions.

CM treatments

At the end of the initial IP consultation, the goals of the CM treatment plan are established and a treatment plan was designed, taking into account the patient’s expectations and main concerns. The IP presents the level of research-based evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of the proposed CM treatment options. The CM treatments are provided by qualified and experienced practitioners, and patients are offered therapeutic interventions which include the following: an IP consultation on the use of herbal and dietary supplements and weekly acupuncture sessions, often in combination with mind-body (relaxation techniques, guided imagery, music therapy, etc.) or manual (e.g., acupressure) techniques.

Referring HCP assessment of impact of CM treatments

Following the follow-up IP assessment, the referring oncology HCPs are asked to provide their assessment of the CM therapeutic process. For this purpose, the following items are scored: changes in overall symptom severity, with a score ranging from −3 (worsening) through 0 (no change) to +3 (improvement), the contribution of the integrative treatment to the oncologist’s ability to treat the patient, with scores ranging from 1 (very little) to 7 (very much), and, finally, the level of communication between the oncology HCP and IP, with a score ranging from 1 (very little) to 7 (very much).

Assessment of patient adherence to CM-recommended intervention

The definition of adherence to the integrative care (AIC) was formulated by a multidisciplinary team of researchers in an earlier multistep design study [21]. Patients who, following the initial IP consultation, underwent CM treatments were grouped according to their AIC program. AIC is defined as the attendance of ≥4 CM treatment sessions, with an interval of no more than 30 days between each meeting.

Definition of optimal IP assessment

The initial and follow-up IP assessments were evaluated independently by two authors (EBA and OGR), taking into account the timing of the intervals between chemotherapy treatments. For patients actively undergoing chemotherapy, an optimal assessment was defined as those cases in which the IP consultations (initial and follow-up) were both conducted at the same interval (within 72 h) with the administration of the identical chemotherapy regimen. Optimal assessment in patients undergoing palliative care, with either no chemotherapy given or else provided as part of the palliative care, was considered according to the intervals between visits at similar intervals following chemotherapy. Non-optimal assessment was defined as those cases in which varied chemotherapy regimens were given prior to the two IP consultations or when one of the assessments was conducted within 10 days after chemotherapy treatment and the other within the third week afterward. In cases where the quality of the assessment was unclear, a team of researchers who were blinded regarding the adherence status (i.e., AIC vs. non-AIC groups) and ESAS scores of the patient was consulted.

Assessment of safety of the CM treatments

Safety of the CM treatments was monitored throughout the study period. Any adverse events which could be attributed to the CM treatment by either the patient, CM practitioner, IP, or referring HCP were entered into the electronic patient file and protocol registry. These included specific symptoms related to the CM treatment and/or reduced efficacy of the chemotherapy regimen.

Data analysis

Data were collated and evaluated using the SPSS software program (version 18; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Variations in demographic data and the prevalence of categorical variables in the two groups of patients (AIC vs. non-AIC) were examined using Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. Differences between continuous variables were evaluated using a t test, this when normality was assumed. For cases of non-normal distribution, a Mann-Whitney U test was used. p value ≤0.05 was considered to be of statistical significance.

A multivariate logistic regression model was developed to predict the factors believed to influence AIC treatment plan. The multivariate logistic regression model was conducted to assess the independency of AIC with the following variables: age, residence distance, cancer site, evidence of metastasis or recurrent disease, oncology care setting (neo-adjuvant, adjuvant, or palliative), chemotherapy that includes taxanes, and cancer- or non-cancer-related CM use.

Difference in specific symptom mean scores as rated in ESAS and MYCAW questionnaires between first and second score changes in AIC vs. non-AIC groups was performed using Mann-Whitney U test.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Carmel Medical Center, Haifa, Ethics Review Board (Helsinki Committee). Participation was voluntary, and no identifying information or other factors which may have compromised participant privacy were involved. No incentive, monetary or otherwise, was offered to the study participants. The study protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01860365).

Results

Demographics, referral, and adherence patterns

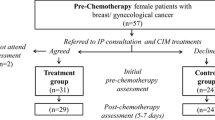

A total of 128 patients were referred by their oncology HCPs to the IP consultation (Fig. 1), with 102 seen by the study IP (79.7 %). Patients who attended the initial IP assessment had been referred by 44 oncologists (44.4 %), 38 nurse oncologists (38.4 %), and 17 psycho-oncologists (17.1 %). Of the 25 patients who did not undergo an IP consultation, 8 had made an appointment but were unable to attend because of their deteriorating medical condition, six were asked to reschedule the appointment later but failed to do so, six could not be located by telephone, two cancelled their appointment with the explanation that they were skeptical regarding the benefits of CM, and two explained that they were not interested in the integrative care program. One patient died before seen by a study IP.

Of the 102 patients who did undergo the initial IP assessment, 78 attended a follow-up IP visit at 6–12 weeks and 6 were scheduled for follow-up but did not attend. The remainder (n = 18) did not undergo follow-up for the following reasons: lived too far from the oncology center (n = 3), died before the scheduled visit (n = 3), hospitalization or deterioration of medical condition(n = 3), unwillingness to undergo CIM treatments (n = 2), reluctance to receive CM treatment within the oncology setting (n = 1), no reason given (n = 5), and an administrative error in scheduling a follow-up appointment (n = 1).

Optimal assessment was achieved in 73 of the 78 patients, with the initial and follow-up IP visits taking place at similar time periods following identical chemotherapy treatments. Initial and follow-up assessments of five patients were not considered to be optimal due to inappropriate timing following chemotherapy or changes made in their treatment regimen. The demographic and disease-related characteristics of the total study cohort (n = 102) were similar at both baseline and follow-up IP visits for both AIC and non-AIC groups (Table 1). The leading concerns of these patients included fatigue (79.8 %), gastrointestinal symptoms (64.6 %), pain and neuropathic symptoms (54.55 %), and emotional distress (45.5 %). No significant differences were found with respect to baseline ESAS scores between the two groups of patients. A logistic multivariate regression model was conducted to predict AIC treatment plan. Non-adherence to integrative care was associated with greater incidence of the presence of metastatic disease (EXP [B], −1.55, 95 % CI 0.048–0.935; p = 0.041).

Impact of CIM treatments on patients’ symptoms and well-being (ESAS tool)

The patient-derived ESAS scores for patients who had been optimally assessed at baseline and follow-up IP visits (n = 73) are presented in Table 2. Almost all of the baseline ESAS scores were similar in both AIC and non-AIC groups, though baseline scores for fatigue were higher (i.e., more severe) in the AIC group (p = 0.005). In the AIC group, ESAS scores improved between initial and follow-up IP visits with respect to pain (p < 0.001), fatigue (p < 0.001), nausea (p = 0.013), depression (p = 0.009), anxiety (p < 0.001), appetite (p < 0.001), sleep (p = 0.002), and feeling of well-being (p < 0.001). In the non-AIC group, a reduction (i.e., improvement) in most ESAS scores was observed, though this was not of statistical significance. With respect to fatigue, while the AIC group showed a mean decrease, in ESAS scores of 1.97 points (±2.65, median 2) between IP visits, an increase in severity (0.27 ± 2.93, median 0) was observed in the non-AIC group (p = 0.033).

Impact of CIM interventions on patients’ leading concerns (MYCAW questionnaire)

Patients in both AIC and non-AIC groups scored similarly with respect to their baseline MYCAW scores regarding their two leading concerns and well-being (3.84 ± 1.46 vs. 3.88 ± 1.65, p = 0.88). In the AIC group, the scores improved significantly (p < 0.0001) between baseline and follow-up assessments for each of the leading concerns and well-being (Table 3). No significant improvement was found in the non-AIC group, though this observation is limited by poor rates of 6–12-week assessments in this group (with MYCAW performed in only two of the 11 patients assessed during the initial visit).

Referring HCP assessment of impact of CM treatments

Following the initial IP consultation, a letter summarizing the consultation was returned to the referring HCP for all of the 102 patients in the cohort. A total of 38 (37.3 %) of the oncology HCPs provided a written reply to the IP, many with specific comments and recommendations regarding the CM treatment process. HCP-IP communication was continued in many instances after the second follow-up IP assessment as well.

A total of 52 of the referring HCPs (66.6 %) completed the questionnaire regarding their impression of the integrative oncology program, which was sent at the end of the follow-up IP assessment. The mean score given by HCPs regarding the contribution of the CM program was 5.22 ± 1.28 (range 1–7; median 6). A score of 6.37 ± 0.70 (median 6) was given for the level of effective communication with the IP.

Discussion

Main findings

The present study explored the impact of an IP-managed integrative oncology model on QOL-related outcomes for gynecologic oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy. We found that most outcomes (as measured by the ESAS study tool) improved in the group of patients who were adherent to the CM treatment plan (AIC group). For non-adherent patients, the improvement for most outcomes was non-significant, with a worsening observed for fatigue (though also non-significant). Referring HCPs gave high scores for their impression contribution made by the CM treatment program on the study outcomes, as well as to the level of effectiveness of their communication with the IP.

Strengths and limitations

The integrative gynecological oncology setting is unique, providing structured and extensive oncologist-IP collaboration. The multidisciplinary team of health care providers includes gynecology oncologists, nurse oncologists, and psycho-oncologists, all working in the same oncology service. In contrast to other studies on the integration of CM in cancer care [8, 22], the present study examined an integrative model of care based on the following core elements: a structured referral process, based on specific QOL-related indications; a central role played by an integrative MD physician (IP), with extensive training in CM and cancer supportive care; the use of reliable and validated assessment tools which address QOL-related outcomes for cancer patients; the “weaving” of a patient-tailored treatment plan, based on patient’s concerns, QOL-related issues, and expectations; the scientific evidence available regarding the effectiveness and safety of the CM treatments offered; and, finally, the use of a feedback process by the referring health care providers in the construction and assessment of the integrative treatment plan.

There are a number of limitations of the present study which need to be addressed in future research. The study format was non-randomized or controlled and did not examine the potential impact of non-specific effects on the study outcomes. The study setting, in which a patient-tailored approach is used for only gynecological oncology patients, may not reflect other gynecological oncology settings. Still, the main objective of the present model is to improve patient QOL, based on established guidelines regarding the effectiveness of CM interventions in reducing chemotherapy-related toxicities and improving well-being. Finally, while the ESAS is an effective study tool for establishing the severity of symptoms and distress, it is limited in its ability to evaluate the complex dynamic of patient symptoms during multiple treatment regimens and other confounding factors. Unfortunately, the use of the MYCAW questionnaire, as an additional assessment tool, had a limited impact on the findings of our study. This was due to a poor follow-up assessment in the non-AIC group. This limitation needs to be addressed in future studies as well, possibly through the use of telephone interviews and electronic media assessment technologies.

Interpretation

The present study setting reflects a patient-tailored rather than symptom-centered research setting, as is the case for randomized controlled studies. This format recognizes and respects patients’ decision making, as described by Andersen et al. [23]. Thus, the lack of a control group of patients needs to be seen not as a major study limitation but rather as an essential aspect in modeling a patient-centered research design, reflecting real-life clinical practice. Another limitation of the study is related to the assessment of fatigue, since the baseline fatigue scores in the AIC group were more severe than in the non-AIC group. This may have resulted in a better delta in the improvement of this outcome measure.

In order to overcome the above limitations, we suggest that future studies set out to compare the two subgroups of patients (AIC and non-AIC). In the present study, despite the fact that patients in the AIC and non-AIC groups were not allocated randomly, they showed similar demographic characteristics as well as parameters regarding disease, chemotherapy, and baseline QOL-related scores, as measured by the ESAS tool. A logistic multivariate regression model found that only the status of the patient regarding the presence of metastatic disease was predictive of adherence to the CM treatment regimen. Although a potential bias may influence patients’ adherence to CM, we suggest that the lack of any significant differences in baseline characteristics of the two groups justifies further analysis of the impact of CM on QOL-related outcomes.

Further research is needed in order to examine the potential impact of the integrative model of care on specific outcomes, such as chemotherapy-induced and cancer-related fatigue (CRF), as well as other QOL-related concerns. In the case of CRF, the difficulties associated with objective assessment in clinical practice require the active participation of oncologist- and patient-reported outcome measures [24]. In the present study, we asked referring oncology HCPs about their view regarding the impact of the integrative treatment model on QOL-related outcomes. Non-specific effects may be more reflective of the rich multidisciplinary context of integrative care and may have a positive impact on oncologist-patient communication and patients’ enhanced sense of holistic and caring approach.

The findings of the present study should be interpreted cautiously and viewed as a pilot model of an integrative approach aimed at alleviating a unique set of patients’ concerns and expectations regarding their well-being. Future studies will need to incorporate the use of more effective and sensitive study tools in order to evaluate the changes in symptom severity and QOL-related outcomes. These should examine to verify not only specific outcomes of the integrative intervention, but also the potential for effecting non-specific effects which, in turn, would empower patients through mechanisms which are more than just a placebo effect. Non-specific effects of integrative care may include elements of patient-centered care (sensitiveness to patient’s health belief model, cross-cultural perspective, etc.), as well as therapist-dependent factors (holistic bio-psycho-social-spiritual approach, open non-judgmental doctor-patient communication on CM, etc.). We also suggest that there is a need for a better understanding of our findings regarding the effect of CM on fatigue. The potential biases of patients’ adherence to integrative care, determined based not only on patient’s compliance but also on other factors as well, need to be taken into account. These include chemotherapy-related hospital admissions, caregiver support, outcomes of non-CM supportive care, and other factors.

Conclusions

Our study presents an integrative model of care in a gynecological oncology setting, in which CM therapies are incorporated with best standard supportive care, with the goal of improving QOL-related outcomes during chemotherapy. We suggest that a patient-tailored integrative approach, provided by IPs trained in both CM and supportive care, may promote patients’ well-being. This is with the support of a multidisciplinary team of health care providers who can target specific indications for referral and who are involved in the integrative medicine therapeutic design and evaluation.

References

Deng GE, Frenkel M, Cohen L, Cassileth BR, Abrams DI, Capodice J, Society for Integrative Oncology et al (2009) Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for integrative oncology: complementary therapies and botanicals. J Soc Integr Oncol 7(3):85–120

Frenkel M, Cohen L, Peterson N, Palmer JL, Swint K, Bruera E (2010) Integrative medicine consultation service in a comprehensive cancer center: findings and outcomes. Integr Cancer Ther 9(3):276–283

Deng G (2008) Integrative Cancer Care in a US Academic Cancer Centre: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Experience. Curr Oncol Suppl 15(2):s108.es68–s108.es71

Helpman L, Ferguson SE, Mackean M, Rana A, Le L, Atkinson MA et al (2011) Complementary and alternative medicine use among women receiving chemotherapy for ovarian cancer in 2 patient populations. Int J Gynecol Cancer 21(3):587–593

Nazik E, Nazik H, Api M, Kale A, Aksu M (2012) Complementary and alternative medicine use by gynecologic oncology patients in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 13(1):21–25

Rhode JM, Patel DA, Sen A, Schimp VL, Johnston CM, Liu JR (2008) Perception and use of complementary and alternative medicine among gynecologic oncology care providers. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 103(2):111–115

Danhauer SC, Tooze JA, Farmer DF, Campbell CR, McQuellon RP, Barrett R et al (2008) Restorative yoga for women with ovarian or breast cancer: findings from a pilot study. J Soc Integr Oncol 6(2):47–58

León-Pizarro C, Gich I, Barthe E, Rovirosa A, Farrús B, Casas F et al (2007) A randomized trial of the effect of training in relaxation and guided imagery techniques in improving psychological and quality-of-life indices for gynecologic and breast brachytherapy patients. Psycho-Oncology 16(11):971–979

Gross AH, Cromwell J, Fonteyn M, Matulonis UA, Hayman LL (2012) Hopelessness and complementary therapy use in patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer Nurs 36(4):256–264

Ahn WS, Kim DJ, Chae GT, Lee JM, Bae SM, Sin JI et al (2004) Natural killer cell activity and quality of life were improved by consumption of a mushroom extract, Agaricus blazei Murill Kyowa, in gynecological cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 14(4):589–594

Sieja K, Talerczyk M (2004) Selenium as an element in the treatment of ovarian cancer in women receiving chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol 93(2):320–327

You Q, Yu H, Wu D, Zhang Y, Zheng J, Peng C (2009) Vitamin B6 points PC6 injection during acupuncture can relieve nausea and vomiting in patients with ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 19(4):567–571

Lu W, Matulonis UA, Doherty-Gilman A, Lee H, Dean-Clower E, Rosulek A, Gibson C et al (2009) Acupuncture for chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in patients with gynecologic malignancies: a pilot randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial. J Altern Complement Med 15(7):745–753

Delia P, Sansotta G, Donato V, Frosina P, Messina G, De Renzis C et al (2007) Use of probiotics for prevention of radiation-induced diarrhea. World J Gastroenterol 13(6):912–915

Etheridge AS, Kroll DJ, Mathews JM (2009) Inhibition of paclitaxel metabolism in vitro in human hepatocytes by Ginkgo biloba preparations. J Diet Suppl 6(2):104–110

Abouzeid AH, Patel NR, Torchilin VP (2014) Polyethylene glycol-phosphatidylethanolamine (PEG-PE)/vitamin E micelles for co-delivery of paclitaxel and curcumin to overcome multi-drug resistance in ovarian cancer. Int J Pharm 464(1–2):178–184

Ben-Arye E, Schiff E, Shapira C, Frenkel M, Shalom T, Steiner M (2012) Modeling an integrative oncology program within a community-centered oncology service in Israel. Patient Educ Couns 89(3):423–429

Ben-Arye E, Schiff E, Steiner M, Keshet Y, Lavie O (2012) Attitudes of patients with gynecological and breast cancer toward integration of complementary medicine in cancer care. Int J Gynecol Cancer 22(1):146–153

Oldenmenger W, de Raaf P, de Klerk C, van der Rijt C (2012) Cut points on 0-10 numeric rating scales for symptoms included in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale in cancer patients: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.06.007

Paterson C, Thomas K, Manasse A, Cooke H, Peace G (2007) Measure Yourself Concerns and Wellbeing (MYCAW): an individualized questionnaire for evaluating outcome in cancer support care that includes complementary therapies. Complement Ther Med 15(1):38–45

Ben-Arie E, Kruger D, Samuels N, Keinan-Boker L, Shalom T, Schiff E (2014) Assessing patient adherence to a complementary medicine treatment regimen in an integrative supportive care setting. Support Care Cancer 22(3):627–644

von Gruenigen VE, Frasure HE, Jenison EL, Hopkins MP, Gil KM (2006) Longitudinal assessment of quality of life and lifestyle in newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients: the roles of surgery and chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol 103(1):120–126

Andersen MR, Sweet E, Lowe KA, Standish LJ, Drescher CW, Goff BA (2012) Involvement in decision-making about treatment and ovarian cancer survivor quality of life. Gynecol Oncol 124(3):465–470

King MT, Stockler MR, Butow P, O’Connell R, Voysey M, Oza AM et al (2014) Development of the measure of ovarian symptoms and treatment concerns: aiming for optimal measurement of patient-reported symptom benefit with chemotherapy for symptomatic ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 24(5):865–867

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mariana Steiner for her mentoring in developing the integrative oncology model.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest exists for any of the authors.

Author contribution

All authors (EBA, NS, ES, OGR, ISS, and OL) contributed to the article’s conception, planning, carrying out, analyzing and writing up of the work.

Details of ethics approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Carmel Medical Center, Haifa, Ethics Review Board. The study protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01860365).

Funding

No funding was provided for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ben-Arye, E., Samuels, N., Schiff, E. et al. Quality-of-life outcomes in patients with gynecologic cancer referred to integrative oncology treatment during chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 23, 3411–3419 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2690-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2690-0