Abstract

Key message

Size limits on molecular movement among female gametes.

Abstract

Cellular decisions can be influenced by information communicated from neighboring cells. Communication can occur via signaling or through the direct transfer of molecules. Movement of RNAs and proteins has frequently been observed among symplastically connected plant cells. In flowering plants, the female gametes, the egg cell and central cell, are closely apposed within the female gametophyte. Here we investigated the ability of fluorescently labeled dyes and small RNAs to move from the Arabidopsis thaliana central cell to the egg apparatus following microinjection. These results define a size limit of at least 20 kDa for symplastic movement between the two gametes, somewhat larger than that previously observed in Torenia fournieri. Our results indicate that symplastic connectivity in Arabidopsis thaliana changes after fertilization and suggest that prior to fertilization mechanisms are in place to facilitate small RNA movement from the central cell to the egg cell and synergids.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The female gametophyte is the site of fertilization in flowering plants. As is typical of most angiosperms, the Arabidopsis thaliana female gametophyte consists of two haploid synergid cells, a haploid egg cell, a diploid central cell, and three haploid antipodal cells. The nuclei of the female gametophyte arise from mitotic division of a single functional megaspore and occupy a common cytoplasm until cellularization commences shortly after the last division (Drews and Yadegari 2004). Despite this, female gametophytic cells have very different fates. The antipodal cells undergo degeneration around the time of fertilization, the synergid cells attract the pollen tube, the egg cell is fertilized by a haploid sperm to develop into the diploid embryo, and the central cell is fertilized by the second haploid sperm to develop into triploid endosperm tissue. Maintenance of gametophytic cell fate is closely tied to position along the ovule micropylar–chalazal axis, but can be altered, for example, in mutants predicted to affect auxin biosynthesis or RNA splicing (Tekleyohans et al. 2017). Several pieces of evidence point to communication among cells of the female gametophyte—genes expressed in one cell can influence the fate of other cells (Kägi et al. 2010; Völz et al. 2012; Krohn et al. 2012; Wu et al. 2012). It is thus important to understand the potential for physical cell-to-cell molecular movement to mediate this communication. Molecular movement between the central cell and egg apparatus (the egg cell and synergids) has been most extensively analyzed in Torenia fournieri, a species in which half of the embryo sac extrudes from the ovule, rendering it physically accessible for manipulation (Han et al. 2000). These studies have shown that the central cell and egg cell are symplastically connected before fertilization, but that permeability decreases substantially as the female gametophyte matures, and is eliminated at fertilization. Despite the importance of A. thaliana as a model genetic system for understanding female gametophyte development and cell fate specification, there has been little investigation of molecular movement within the female gametophyte. Like in other angiosperms, there is no cell wall between the A. thaliana egg and central cell (Mansfield and Briarty 1991), suggesting reduced barriers to movement compared to other plant tissues. We previously developed a microinjection protocol for A. thaliana that allowed us to microinject the central cell of living ovules (Völz et al. 2013). Here, we used this experimental system to analyze the ability of larger macromolecules, including fluorescent tracers and labeled 24 nucleotide small RNAs (with two dyes as an energy transfer pair, “RNA traffic lights” (Walter et al. 2017; Arndt et al. 2016; Holzhauser and Wagenknecht 2013)) to move from the central cell to the egg apparatus before fertilization and from the primary endosperm to the zygote after fertilization.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Plants were grown on soil in growth chambers under long-day conditions (16 h light and 8 h dark) at approximately 18 °C. All experiments were performed on wild-type Ler plants or FGR7.0 Ler plants (Völz et al. 2013). The largest closed flower buds were emasculated and then pollinated after 1–2 days.

Ovule and seed microinjection

Ovules/seeds were removed from pistils/siliques while maintaining attachment to the placenta. Tissue was mounted on pads of C + media (4 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 14.5% sucrose, 3% Polyethylene glycol 4000, 0.01% H3BO3, and MilliQ H2O), surrounded by C- media (C + media with 2% alginic acid in place of CaCl2) and then covered with halocarbon oil. Injections were performed as previously described (Völz et al. 2013). A piezo-stepper (PMZ 20, Frankenberger, Filching, Germany) and a FemtoJet (Eppendorf) were used in tandem to perform the pressure microinjections under an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Leica CTR 6000). The approximate concentration of RNA A or RNA B in microinjection solution was 1 ng/µL.

Microscopy

Confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed on an LSM 780 (Zeiss) with the following conditions: FITC excitation: 488 nm, FITC emission: 499–525 nm; rhodamine excitation: 561 nm, rhodamine emission: 570–695 nm; RNA acceptor excitation: 561 nm, RNA acceptor emission: 606–695 nm; RNA donor excitation: 458 nm, RNA donor emission: 472–543 nm. Fluorescent tracer imaging occurred between 5 and 95 min post-injection. sRNA injection imaging occurred between 30 min and 4 h post-injection. Determinations of molecular movement were made blind by two authors.

Image manipulation

Image intensities were scaled to the maximum signal level found in each channel. Brightness adjustments were performed identically for every channel within an individual image. All images in Figs. 1 and 2 represent a single focal plane. FIJI (Schindelin et al. 2012) was used to apply a Gaussian filter (radius of 2.0 pixels) to each micrograph.

Assaying passive dye permeability in the female gametophyte before and after fertilization. a Schematic of Arabidopsis ovule. b Pre-fertilization co-injection of Ler with 10 kDa FITC (green) and 70 kDa rhodamine (red). Image captured 45 min following injection. c Pre-fertilization co-injection of Ler with 20 kDa FITC (green) and 70 kDa rhodamine. Image captured 80 min following injection. Yellow arrowheads indicate the position of the egg apparatus (the cluster of the egg cell and synergid cells). d Schematic of the developing seed, about 18 h after pollination. e Post-fertilization injection of Ler with 10 kDa FITC. Image captured 90 min after injection. f Post-fertilization injection of Ler FGR7.0 with 10 kDa FITC. RFP (red) is expressed within the zygote. Image captured 60 min after injection. Yellow arrowheads mark the position of the zygote. All scale bars, 20 μm

Assaying small RNA movement between the cells of the female gametophyte using a FRET system a Pre-fertilization injection of 24 nucleotide RNA “A.” Total sRNA signal shown in red, single-stranded signal shown is green. Movement is observed. b Pre-fertilization injection of 24 nucleotide RNA “B,” showing total sRNA signal. Image captured 60 min following injection. Movement is observed. c Pre-fertilization injection of 24-nucleotide RNA “B,” showing total sRNA signal. Image captured 65 min following injection. No movement is observed. Yellow arrowheads indicate the position of the egg apparatus. Scale bars, 20 μm

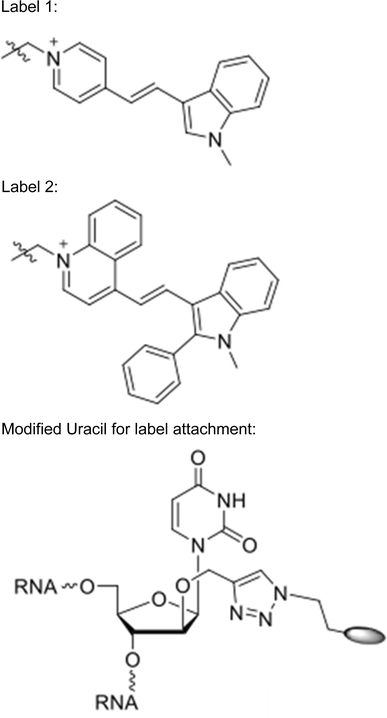

Small RNA sequences and construction

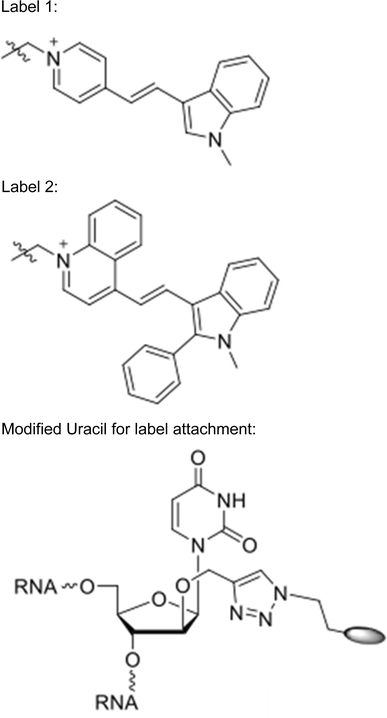

Labeled small RNAs were synthesized in the manner of Walter et al. (2017).

-

RNA “A”:

-

5′ (PO3 2−A)AA GAC AAU GAC AAA (U^)UC UUG GC(G-OMe) 3′

-

3′ (OMe-C)A UUU CUG UUA CUG UU(U*) AAG AAC (C-PO3 2−) 5′

-

RNA “B”:

-

5′ (PO3 2−U)AU AUG CAA GUC CGG CCA (U^)AC AG(C-OMe) 3′

-

3′ (OMe-C)U AUA UAC GUU CAG GCC GG(U*) AUG (U-PO3 2−) 5′

-

Positions marked with * were conjugated to Label 1.

-

Positions marked with ^ were conjugated to Label 2.

Results

Limits on passive dye diffusion in the female gametophyte

We measured the ability of fluorescent dyes ranging in size from 805 Da to 70 kDa to diffuse from the central cell to the egg apparatus before fertilization. Ler flowers were emasculated and allowed to mature for 1–2 days. Ovules were removed from pistils while still connected to the placenta and embedded on media plates that allowed for maintenance of ovule viability over the course of the experiment (Völz et al. 2013). Smaller fluorescent FITC dyes (green) were coinjected into the central cell along with 70 kDa rhodamine dye (red). At 1 and 2 days after emasculation (DAE), 805 Da, 10 kDa, and 20 kDa dyes entered the egg cell within 10 min of injection into the central cell (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Z-stack imagery of the entire depth of the female gametophyte indicated that the dye signal was found both within the egg cell and synergid cells (data not shown). By contrast, in 35 injections performed 1–2 DAE, movement of the 70 kDa dye out of the central cell was not observed (Table 1). These results indicate that the molecular limit on passive movement in the mature A. thaliana female gametophyte is between 20 and 70 kDa.

Passive dye diffusion is restricted after fertilization

We tested whether fertilization altered the ability of dyes to diffuse from the 1–2 cell endosperm to the zygote (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Most injections were performed approximately 18 h after pollination (HAP), by which point it was clear that fertilization had occurred throughout the silique. In contrast to the results obtained before fertilization, we were unable to detect movement of 10 or 20 kDa dyes out of the endosperm. Lack of movement was apparent in wild-type ovules (Fig. 1e) and in the FGR7.0 line (Fig. 1f), in which the egg cell was labeled with RFP. These results suggest that fertilization is associated with rapid restriction of symplastic connections between the central cell and egg cell.

Labeled small RNAs move from central cell to egg cell

With the approximate diffusion limits assayed, we next tested the ability of fluorescently labeled sRNAs to move from the central cell to the egg apparatus. We independently injected two double-stranded RNA sequences into the central cell: RNA “A” corresponded to a 24 nt small RNA highly expressed within the developing seed (Pignatta et al. 2014), whereas RNA “B” corresponded to a 24 nt sequence not found within the A. thaliana genome. The sRNAs were labeled for use in fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments to distinguish single- and double-stranded molecules. In one microscopy channel (red), the acceptor dye (label 2) was excited directly and the same acceptor dye’s emission was monitored, providing an additive measure of both single- and double-stranded sRNA. The other channel (green) monitored the fluorescence of the donor fluorophore that was not transferred to the acceptor following excitation of the donor, thus denoting single-stranded sRNAs. sRNA duplexes are estimated to be about 16 kDa in size, with the dye pair contributing slightly less than 1 kDa. The stability of sRNAs post-injection and the photochemical stability of the applied dyes (Bohländer and Wagenknecht 2015; Walter et al. 2015) was seemingly quite high, with the signal remaining detectable at least four hours (the longest period tested) after microinjection into the central cell. In 10 of 11 microinjections, RNA “A” could be detected in the egg cell after injection into the central cell (Fig. 2a). Signal from both single and double-stranded RNAs was observed in the egg cell. By contrast, results from RNA “B” were equivocal—movement from central cell to egg cell was observed in only 4 of 8 microinjections (Fig. 2b, c).

Discussion

These results indicate that the central cell and egg apparatus remain symplastically connected even after cellularization and suggest that multiple types of macromolecules may have the ability to be passively shared among cells of the A. thaliana female gametophyte. Our findings also reveal differences between A. thaliana and Torenia, the species in which these questions have been most closely examined. Unlike in Torenia (Han et al. 2000), we did not observe a decrease in the ability of molecules to move between cells as the female gametophyte matured (Table 1, compare 1 and 2 DAE). Additionally, the size of molecules that diffuse between the central cell and egg cell is larger in A. thaliana than in Torenia. At maturity, molecules of 3 kDa could move from the central cell to egg cell in Torenia about half the time, whereas earlier in development movement of 10 kDa FITC was observed (Han et al. 2000). Our studies at 2 DAE, when the female gametophyte is mature, indicate that tracers up to 20 kDa can freely pass between the cells. The size range for movement in the female gametophyte is thus similar to that observed in Arabidopsis embryos, young seedlings, and the seed outer integuments (Kim et al. 2005; Stadler et al. 2005). Analogous to findings from Torenia (Han et al. 2000), our data indicate symplastic isolation between the zygote and endosperm shortly after fertilization, suggesting that gamete fusion triggers modulation of the egg and or central cell extracellular matrix. Symplastic isolation has also been observed at later stages of Arabidopsis embryo and endosperm development (Stadler et al. 2005; Ingram 2010). It is not yet clear whether embryo–endosperm isolation is a common theme in flowering plants, as suspensor and endosperm share plasmodesmata in Crassulaceae (Kozieradzka-Kiszkurno and Plancho 2012), indicating the potential for molecular movement between these compartments.

Finally, we also detected movement of labeled small RNAs before fertilization. In Torenia, FITC-labeled morpholino 25 nt antisense oligomers injected into the central cells moved to and functioned in the synergid cells (Okuda et al. 2009). Our findings suggest that similar knockdown experiments are possible in A. thaliana. Additionally, this system may also facilitate in understanding properties of endogenous small RNAs.

Author contribution statement

RME, RG, and MG conceived and designed experiments. RME and AH conducted experiments and analyzed data. HKW and HAW contributed new reagents. RME, RG, and MG wrote the manuscript.

References

Arndt S, Walter H-K, Wagenknecht H-A (2016) Synthesis of wavelength-shifting DNA hybridization probes by using photostable cyanine dyes. J Vis Exp 113:e54121

Bohländer PR, Wagenknecht H-A (2015) Bright and photostable cyanine-styryl chromophores with green and red fluorescence color for DNA staining. Method Appl Fluoresc 3:044003

Drews GN, Yadegari R (2004) Female gametophyte development. Plant Cell 16:S133–S141

Han YZ, Huang BQ, Zee SY, Yuan M (2000) Symplastic communication between the central cell and the egg apparatus cells in the embryo sac of Torenia fournieri Lind. before and during fertilization. Planta 211:158–162

Holzhauser C, Wagenknecht H-A (2013) DNA and RNA “Traffic Lights”: synthetic wavelength-shifting fluorescent probes based on nucleic acid base substitutes for molecular imaging. J Org Chem 78:7373–7379

Ingram GC (2010) Family life at close quarters: communication and constraint in angiosperm seed development. Protoplasma 247:195–214

Kägi C, Baumann N, Nielsen N, Stierhof YD, Groß-Hardt R (2010) The gametic central cell of Arabidopsis determines the lifespan of adjacent accessory cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:22350–22355

Kim I, Cho E, Crawford K, Hempel FD, Zambryski PC (2005) Cell-to-cell movement of GFP during embryogenesis and seedling development in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:2227–2231

Kozieradzka-Kiszkurno M, Plancho BJ (2012) Are there symplastic connections between the endosperm and embryo in some angiosperms?—a lesson from the Crassulaceae family. Protoplasma 249:1081–1089

Krohn NG, Lausser A, Juranic M, Dresselhaus T (2012) Egg cell signaling by the secreted peptide ZmEAL1 controls antipodal cell fate. Dev Cell 23:219–225

Mansfield SG, Briarty SE (1991) Early embryogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. I. The mature embryo sac. Can J Bot 69:447–460

Okuda S et al (2009) Defensin-like polypeptide LUREs are pollen tube attractants secreted from the synergid cells. Nature 458:357–361

Pignatta D, Erdmann RM, Scheer E, Picard CL, Bell GW, Gehring M (2014) Natural epigenetic polymorphisms lead to intraspecific variation in Arabidopsis gene imprinting. eLife 3:e03198

Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M et al (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9:676–682

Stadler R, Lauterbach C, Sauer N (2005) Cell-to-cell movement of green fluorescent protein reveals post-phloem transport in the outer integument and identifies symplastic domains in Arabidopsis seeds and embryos. Plant Physiol 139:701–712

Tekleyohans DG, Nakel T, Groß-Hardt R (2017) Patterning the female gametophyte of flowering plants. Plant Physiol 173:122–129

Völz R, von Lyncker L, Baumann N, Dresselhaus T, Sprunck S, Groß-Hardt R (2012) LACHESIS-dependent egg-cell signaling regulates the development of female gametophytic cells. Development 139:498–502

Völz R, Heydlauff J, Ripper D, von Lyncker L, Groß-Hardt R (2013) Ethylene signaling is required for synergid degeneration and the establishment of a pollen tube block. Dev Cell 25:310–316

Walter H-K, Bohländer PR, Wagenknecht H-A (2015) Development of a wavelength-shifting fluorescent module for the adenosine aptamer using photostable cyanine dyes. ChemistryOpen 4:92–96

Walter H-K, Olshausen B, Schepers U, Wagenknecht H-A (2017) A postsynthetically 2′-“clickable” uridine with arabino configuration and its application for fluorescent labeling and imaging of DNA. Beilstein J Org Chem 13:127–137

Wu JJ, Peng XB, Li WW, He R, Xin HP, Sun MX (2012) Mitochondrial GCD1 dysfunction reveals reciprocal cell-to-cell signaling during the maturation of the Arabidopsis female gametes. Dev Cell 23:1043–1058

Acknowledgements

RME was funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF) graduate research fellowship and a short-term research grant from the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service). This work was also supported by NSF Grant 1453459 to MG. HAW and HKW thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (GRK 2039/1) and KIT for financial support. We thank Andreas Ellrott (Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology) for technical assistance with confocal microscopy and Wendy Salmon (Whitehead Institute) for helpful discussions regarding image analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by Dolf Weijers.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Erdmann, R.M., Hoffmann, A., Walter, HK. et al. Molecular movement in the Arabidopsis thaliana female gametophyte. Plant Reprod 30, 141–146 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00497-017-0304-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00497-017-0304-3