Abstract

Kidney disease and its related comorbidities impose a large public health burden. Despite this, the number of clinical trials in nephrology lags behind many other fields. An important factor contributing to the relatively slow pace of nephrology trials is that existing clinical endpoints have significant limitations. “Hard” endpoints for chronic kidney disease, such as progression to end-stage renal disease, may not be reached for decades. Traditional biomarkers, such as serum creatinine in acute kidney injury, may lack sensitivity and predictive value. Finding new biomarkers to serve as surrogate endpoints is therefore an important priority in kidney disease research and may help to accelerate nephrology clinical trials. In this paper, I first review key concepts related to the selection of clinical trial endpoints and discuss statistical and regulatory considerations related to the evaluation of biomarkers as surrogate endpoints. This is followed by a discussion of the challenges and opportunities in developing novel biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in three major areas of nephrology research: acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Himmelfarb J (2007) Chronic kidney disease and the public health: gaps in evidence from interventional trials. JAMA 297:2630–2633

Strippoli GFM, Craig JC, Schena FP (2004) The number, quality, and coverage of randomized controlled trials in nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol 15:411–419

Boissel JP, Collet JP, Moleur P, Haugh M (1992) Surrogate endpoints: a basis for a rational approach. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 43:235–244

Biomarkers Definitions Working Group (2001) Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin Pharmacol Ther 69:89–95

Prentice RL (1989) Surrogate endpoints in clinical trials: definition and operational criteria. Stat Med 8:431–440

Inker LA, Lambers Heerspink HJ, Mondal H, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Noubary F, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS (2014) GFR decline as an alternative end point to kidney failure in clinical trials: a meta-analysis of treatment effects from 37 randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis 64:848–859

Haase-Fielitz A, Haase M, Devarajan P (2014) Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a biomarker of acute kidney injury: a critical evaluation of current status. Ann Clin Biochem 51:335–351

Thompson A, Lawrence J, Stockbridge N (2014) GFR decline as an end point in trials of CKD: a viewpoint from the FDA. Am J Kidney Dis 64:836–837

Levey AS, Cattran D, Friedman A, Miller WG, Sedor J, Tuttle K, Kasiske B, Hostetter T (2009) Proteinuria as a surrogate outcome in CKD: report of a scientific workshop sponsored by the national kidney foundation and the US food and drug administration. Am J Kidney Dis 54:205–226

De Gruttola VG, Clax P, DeMets DL, Downing GJ, Ellenberg SS, Friedman L, Gail MH, Prentice R, Wittes J, Zeger SL (2001) Considerations in the evaluation of surrogate endpoints in clinical trials. Summary of a national institutes of health workshop. Control Clin Trials 22:485–502

Fleming TR, Demets DL (1996) Surrogate end points in clinical trials: are we being misled? Ann Intern Med 125:605–613

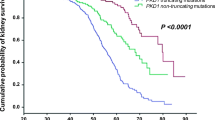

Schrier RW, Brosnahan G, Cadnapaphornchai MA, Chonchol M, Friend K, Gitomer B, Rossetti S (2014) Predictors of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease progression. J Am Soc Nephrol 25:2399–2418

Cadnapaphornchai MA, George DM, McFann K, Wang W, Gitomer B, Strain JD, Schrier RW (2014) Effect of pravastatin on total kidney volume, left ventricular mass index, and microalbuminuria in pediatric autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9:889–896

Laufs U (2003) Beyond lipid-lowering: effects of statins on endothelial nitric oxide. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 58:719–731

Nishikawa H, Miura S, Zhang B, Shimomura H, Arai H, Tsuchiya Y, Matsuo K, Saku K (2004) Statins induce the regression of left ventricular mass in patients with angina. Circ J 68:121–125

Fleming TR, Prentice RL, Pepe MS, Glidden D (1994) Surrogate and auxiliary endpoints in clinical trials, with potential applications in cancer and AIDS research. Stat Med 13:955–968

Buyse M, Molenberghs G, Burzykowski T, Renard D, Geys H (2000) The validation of surrogate endpoints in meta-analyses of randomized experiments. Biostatistics 1:49–67

Freedman LS, Graubard BI, Schatzkin A (1992) Statistical validation of intermediate endpoints for chronic diseases. Stat Med 11:167–178

Mildvan D, Landay A, De Gruttola V, Machado SG, Kagan J (1997) An approach to the validation of markers for use in AIDS clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis 24:764–774

Bycott PW, Taylor JM (1998) An evaluation of a measure of the proportion of the treatment effect explained by a surrogate marker. Control Clin Trials 19:555–568

Lin DY, Fleming TR, De Gruttola V (1997) Estimating the proportion of treatment effect explained by a surrogate marker. Stat Med 16:1515–1527

De Gruttola V, Fleming T, Lin DY, Coombs R (1997) Perspective: validating surrogate markers—are we being naive? J Infect Dis 175:237–246

Weir CJ, Walley RJ (2006) Statistical evaluation of biomarkers as surrogate endpoints: a literature review. Stat Med 25:183–203

Flandre P, Saidi Y (1999) Estimating the proportion of treatment effect explained by a surrogate marker. Stat Med 18:107–109

Buyse M, Molenberghs G (1998) Criteria for the validation of surrogate endpoints in randomized experiments. Biometrics 54:1014–1029

Alonso A, Molenberghs G, Burzykowski T, Renard D, Geys H, Shkedy Z, Tibaldi F, Abrahantes JC, Buyse M (2004) Prentice’s approach and the meta-analytic paradigm: a reflection on the role of statistics in the evaluation of surrogate endpoints. Biometrics 60:724–728

Alonso A, Van der Elst W, Molenberghs G, Buyse M, Burzykowski T (2014) On the relationship between the causal-inference and meta-analytic paradigms for the validation of surrogate endpoints. Biometrics. doi:10.1111/biom.12245

Buyse M, Molenberghs G, Paoletti X, Oba K, Alonso A, Van der Elst W, Burzykowski T (2015) Statistical evaluation of surrogate endpoints with examples from cancer clinical trials. Biom J. doi:10.1002/bimj.201400049

Burzykowski T, Buyse M (2006) Surrogate threshold effect: an alternative measure for meta-analytic surrogate endpoint validation. Pharm Stat 5:173–186

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ (1982) The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 143:29–36

Greenland P, O’Malley PG (2005) When is a new prediction marker useful? A consideration of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 and C-reactive protein for stroke risk. Arch Intern Med 165:2454–1456

Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS (2008) Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 27:157–172, discussion 207–212

Hilden J, Gerds TA (2014) A note on the evaluation of novel biomarkers: do not rely on integrated discrimination improvement and net reclassification index. Stat Med 33:3405–3014

Kerr KF, McClelland RL, Brown ER, Lumley T (2011) Evaluating the incremental value of new biomarkers with integrated discrimination improvement. Am J Epidemiol 174:364–374

Kerr KF, Wang Z, Janes H, McClelland RL, Psaty BM, Pepe MS (2014) Net reclassification indices for evaluating risk prediction instruments: a critical review. Epidemiology 25:114–121

Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 2013, U.S.C. Sec. 355. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2013-title21/pdf/USCODE-2013-title21-chap9-subchapV-partAsec355.pdf

Temple R (1999) Are surrogate markers adequate to assess cardiovascular disease drugs? JAMA 282:600–604

[No authors listed] (1992) New drug, antibiotic, and biological drug product regulations; accelerated approval—FDA. Final rule. Fed Regist 57:58942–58960

International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (1998) ICH harmonised tripartite guideline: statistical principles for clinical trials E9. Fed Regist 63:49583

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2009) FDA/CDER Biomarker Qualification Program. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DrugDevelopmentToolsQualificationProgram/ucm284076.htm. Accessed 10 Mar 2015

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2004) FDA Critical Path Initiative. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/scienceresearch/specialtopics/criticalpathinitiative/default.htm. Accessed 10 Mar 2015

Amur S (2013) Biomarker qualification at CDER/FDA. In: EMA-FDA Webinar. Available at: http://www.imi.europa.eu/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/Webinar/IMIwebinaronregulatoryacceptance/5_-_Shashi_Amur[1].pdf. Accessed 9 Mar 2015

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2014) Guidance for industry and FDA staff: qualification process for drug development tools. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM230597.pdf. Accessed 10 Mar 2015

Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P; Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative workgroup (2004) Acute renal failure—definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the second international consensus conference of the acute dialysis quality initiative (ADQI) group. Crit Care 8:R204–R212

Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A (2007) Acute kidney injury network (2007) acute kidney injury network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care 11:R31

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group (2012) KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2:1–138

Devarajan P, Murray P (2014) Biomarkers in acute kidney injury: are we ready for prime time? Nephron Clin Pract 127:176–179

Endre ZH, Pickering JW (2014) Cell cycle arrest biomarkers win race for AKI diagnosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 10:683–685

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2014) FDA news release. FDA allows marketing of the first test to assess risk of developing acute kidney injury. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm412910.htm. Accessed 11 Mar 2015

Kashani K, Al-Khafaji A, Ardiles T, Artigas A, Bagshaw SM, Bell M, Bihorac A, Birkhahn R, Cely CM, Chawla LS, Davison DL, Feldkamp T, Forni LG, Gong MN, Gunnerson KJ, Haase M, Hackett J, Honore PM, Hoste EA, Joannes-Boyau O, Joannidis M, Kim P, Koyner JL, Laskowitz DT, Lissauer ME, Marx G, McCullough PA, Mullaney S, Ostermann M, Rimmelé T, Shapiro NI, Shaw AD, Shi J, Sprague AM, Vincent JL, Vinsonneau C, Wagner L, Walker MG, Wilkerson RG, Zacharowski K, Kellum JA (2013) Discovery and validation of cell cycle arrest biomarkers in human acute kidney injury. Crit Care 17:R25

Billings FT IV, Shaw AD (2014) Clinical trial endpoints in acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract 127:89–93

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) (2013) KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3:1–150

Levey AS, Inker LA, Matsushita K, Greene T, Willis K, Lewis E, de Zeeuw D, Cheung AK, Coresh J (2014) GFR decline as an end point for clinical trials in CKD: a scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation and the US Food and Drug Administration. Am J Kidney Dis 64:821–835

Lambers Heerspink HJ, Weldegiorgis M, Inker LA, Gansevoort R, Parving HH Dwyer JP, Mondal H, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS, de Zeeuw D (2014) Estimated GFR decline as a surrogate end point for kidney failure: a post hoc analysis from the reduction of End points in non-insulin-dependent diabetes with the angiotensin II antagonist losartan (RENAAL) study and irbesartan diabetic nephropathy trial. Am J Kidney Dis 63:244–250

Coresh J, Turin TC, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Ballew SH, Appel LJ, Arima H, Chadban SJ, Cirillo M, Djurdjev O, Green JA, Heine GH, Inker LA, Irie F, Ishani A, Ix JH, Kovesdy CP, Marks A, Ohkubo T, Shalev V, Shankar A, Wen CP, de Jong PE, Iseki K, Stengel B, Gansevoort RT, Levey AS, CKD Prognosis Consortium (2014) Decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate and subsequent risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality. JAMA 311:2518–3251

Lambers Heerspink HJ, Tighiouart H, Sang Y, Ballew S, Mondal H, Matsushita K, Coresh J, Levey AS, Inker LA (2014) GFR decline and subsequent risk of established kidney outcomes: a meta-analysis of 37 randomized controlled trials. Am J Kidney Dis 64:860–866

Schnaper HW, Furth SL, Yao LP (2015) Defining new surrogate markers for CKD progression. Pediatr Nephrol 30:193–198

Fleming TR, Powers JH (2012) Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in clinical trials. Stat Med 31:2973–2984

Thompson A (2012) Proteinuria as a surrogate end point–more data are needed. Nat Rev Nephrol 8:306–309

Redon J, Martinez F (2012) Microalbuminuria as surrogate endpoint in therapeutic trials. Curr Hypertens Rep 14:345–349

Lambers Heerspink HJ, de Zeeuw D (2010) Debate: PRO position. Should microalbuminuria ever be considered as a renal endpoint in any clinical trial? Am J Nephrol 31:458–461, discussion 468

Glassock RJ (2010) Debate: CON position. Should microalbuminuria ever be considered as a renal endpoint in any clinical trial? Am J Nephrol 31:462–465, discussion 466–467

Wong H, Vivian L, Weiler G, Filler G (2004) Patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease hyperfiltrate early in their disease. Am J Kidney Dis 43:624–628

Chapman AB, Bost JE, Torres VE, Torres VE, Guay-Woodford L, Bae KT, Landsittel D, Li J, King BF, Martin D, Wetzel LH, Lockhart ME, Harris PC, Moxey-Mims M, Flessner M, Bennett WM, Grantham JJ (2012) Kidney volume and functional outcomes in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7:479–486

Grantham JJ, Torres VE, Chapman AB, Guay-Woodford LM, Bae KT, King BF Jr, Wetzel LH, Baumgarten DA, Kenney PJ, Harris PC, Klahr S, Bennett WM, Hirschman GN, Meyers CM, Zhang X, Zhu F, Miller JP, Investigators CRISP (2006) Volume progression in polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 354:2122–2130

Chapman AB, Guay-Woodford LM, Grantham JJ et al (2003) Renal structure in early autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): the consortium for radiologic imaging studies of polycystic kidney disease (CRISP) cohort. Kidney Int 64:1035–1045

Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. (2013) Tolvaptan phase 3 efficacy and safety study in ADPKD (TEMPO3/4). Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00428948. Accessed 10 Mar 2015

Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Grantham JJ, Higashihara E, Perrone RD, Krasa HB, Ouyang J, Czerwiec FS, TEMPO 3:4 Trial Investigators (2012) Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 367:2407–2418

Lawrence J, Thompson A (2013) NDA 204441 Tolvaptan clinical and statistical findings, cardiovascular and renal drugs advisory committee meeting, August 5, 2013. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/CardiovascularandRenalDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM364582.pdf. Accessed 10 Mar 2015

Kawano H, Muto S, Ohmoto Y, Iwata F, Fujiki H, Mori T, Yan L, Horie S (2014) Exploring urinary biomarkers in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. doi:10.1007/s10157-014-1078-7

Kocyigit I, Eroglu E, Orscelik O, Unal A, Gungor O, Ozturk F, Karakukcu C, Imamoglu H, Sipahioglu MH, Tokgoz B, Oymak O (2014) Pentraxin 3 as a novel bio-marker of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Nephrol 27:181–186

Boertien WE, Meijer E, Li J, Bost JE, Struck J, Flessner MF, Gansevoort RT, Torres VE, Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease CRISP (2013) Relationship of copeptin, a surrogate marker for arginine vasopressin, with change in total kidney volume and GFR decline in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: results from the CRISP cohort. Am J Kidney Dis 61:420–429

Kistler AD, Serra AL, Siwy J, Poster D, Krauer F, Torres VE, Mrug M, Grantham JJ, Bae KT, Bost JE, Mullen W, Wüthrich RP, Mischak H, Chapman AB (2013) Urinary proteomic biomarkers for diagnosis and risk stratification of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a multicentric study. PLoS ONE 8:e53016

Torres VE, King BF, Chapman AB, Brummer ME, Bae KT, Glockner JF, Arya K, Risk D, Felmlee JP, Grantham JJ, Guay-Woodford LM, Bennett WM, Klahr S, Meyers CM, Zhang X, Thompson PA, Miller JP, Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease (CRISP) (2007) Magnetic resonance measurements of renal blood flow and disease progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2:112–120

Helal I, Reed B, Schrier RW (2012) Emergent early markers of renal progression in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease patients: implications for prevention and treatment. Am J Nephrol 36:162–167

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hartung is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number KL2TR000139. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official view of NCATS or the NIH.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hartung, E.A. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 31, 381–391 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-015-3104-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-015-3104-8