Abstract

Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) and head mount displays (HMDs) have been advanced for multimedia and information technologies but have scarcely been used in surgical training. Motion sickness and individual psychological changes have been associated with VR. The goal was to observe first experiences and performance scores using a new combined highly immersive virtual reality (IVR) laparoscopy setup.

Methods

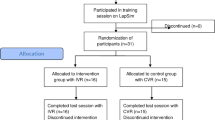

During the study, 10 members of the surgical department performed three tasks (fine dissection, peg transfer, and cholecystectomy) on a VR simulator. We then combined a VR HMD with the VR laparoscopic simulator and displayed the simulation on a 360° video of a laparoscopic operation to create an IVR laparoscopic simulation. The tasks were then repeated. Validated questionnaires on immersion and motion sickness were used for the study.

Results

Participants’ times for fine dissection were significantly longer during the IVR session (regular: 86.51 s [62.57 s; 119.62 s] vs. IVR: 112.35 s [82.08 s; 179.40 s]; p = 0.022). The cholecystectomy task had higher error rates during IVR. Motion sickness did not occur at any time for any participant. Participants experienced a high level of exhilaration, rarely thought about others in the room, and had a high impression of presence in the generated IVR world.

Conclusion

This is the first clinical and technical feasibility study using the full IVR laparoscopy setup combined with the latest laparoscopic simulator in a 360° surrounding. Participants were exhilarated by the high level of immersion. The setup enables a completely new generation of surgical training.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Nagendran M, Gurusamy KS, Aggarwal R, Loizidou M, Davidson BR (2013) Virtual reality training for surgical trainees in laparoscopic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8:CD006575. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006575.pub3

Satava RM (1993) 3-D vision technology applied to advanced minimally invasive surgery systems. Surg Endosc 7(5):429–431

van Dongen KW, van der Wal WA, Rinkes IH, Schijven MP, Broeders IA (2008) Virtual reality training for endoscopic surgery: voluntary or obligatory? Surg Endosc 22(3):664–667. doi:10.1007/s00464-007-9456-9

Abelson JS, Silverman E, Banfelder J, Naides A, Costa R, Dakin G (2015) Virtual operating room for team training in surgery. Am J Surg 210(3):585–590. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.01.024

Powers KA, Rehrig ST, Irias N, Albano HA, Malinow A, Jones SB, Moorman DW, Pawlowski JB, Jones DB (2008) Simulated laparoscopic operating room crisis: an approach to enhance the surgical team performance. Surg Endosc 22(4):885–900. doi:10.1007/s00464-007-9678-x

Tan SB, Pena G, Altree M, Maddern GJ (2014) Multidisciplinary team simulation for the operating theatre: a review of the literature. ANZ J Surg 84(7–8):515–522. doi:10.1111/ans.12478

Sharar SR, Miller W, Teeley A, Soltani M, Hoffman HG, Jensen MP, Patterson DR (2008) Applications of virtual reality for pain management in burn-injured patients. Expert Rev Neurother 8(11):1667–1674. doi:10.1586/14737175.8.11.1667

Nararro-Haro MV, Hoffman HG, Garcia-Palacios A, Sampaio M, Alhalabi W, Hall K, Linehan M (2016) The use of virtual reality to facilitate mindfulness skills training in dialectical behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder: a case study. Front Psychol 7:1573. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01573

Keshavarz B, Hecht H (2011) Validating an efficient method to quantify motion sickness. Human Factors 53(4):415–426. doi:10.1177/0018720811403736

Madary M, Metzinger TK (2016) Real virtuality: a code of ethical conduct. Recommendations for good scientific practice and the consumers of VR-technology. Front Robot AI 3:3. doi:10.3389/frobt.2016.00003

Palter VN, Grantcharov TP (2014) Individualized deliberate practice on a virtual reality simulator improves technical performance of surgical novices in the operating room: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 259(3):443–448. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000254

Paschold M, Huber T, Kauff DW, Buchheim K, Lang H, Kneist W (2014) Preconditioning in laparoscopic surgery–results of a virtual reality pilot study. Langenbecks Arch Surg 399(7):889–895. doi:10.1007/s00423-014-1224-4

Nichols S, Haldane C, Wilson JR (2000) Measurement of presence and its consequences in virtual environments. Int J Hum Comput Stud 52(3):471–491. doi:10.1006/ijhc.1999.0343

Bekelis K, Calnan D, Simmons N, MacKenzie TA, Kakoulides G (2016) Effect of an immersive preoperative virtual reality experience on patient reported outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. doi:10.1097/sla.0000000000002094

Sankaranarayanan G, Li B, Manser K, Jones SB, Jones DB, Schwaitzberg S, Cao CG, De S (2016) Face and construct validation of a next generation virtual reality (Gen2-VR) surgical simulator. Surg Endosc 30(3):979–985. doi:10.1007/s00464-015-4278-7

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Y. Huber, L. Nola, S. Mädge, M. Pocha, and V. Tripke and for their support during the recording of the OR video sequence. The authors also thank B. Golla and M. Kosta for technical support. Finally, we appreciate the support from and discussions with H. Hecht, the Department of General Experimental Psychology, the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz.

Funding

Financial support for the laparoscopic simulator was provided by the medical education project “MAICUM” from the Medical Centre of the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz. Funding for the additional immersive virtual reality hardware was provided by intramural funding from the Medical Centre of the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz and an educational intramural funding by the Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The authors Tobias Huber, Markus Paschold, Christian Hansen, Tom Wunderling, Hauke Lang and Werner Kneist have no conflict of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huber, T., Paschold, M., Hansen, C. et al. New dimensions in surgical training: immersive virtual reality laparoscopic simulation exhilarates surgical staff. Surg Endosc 31, 4472–4477 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5500-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5500-6