Abstract

Background

The effectiveness of an esophagomyotomy for dysphagia in elderly patients with achalasia has been questioned. This study was designed to provide an answer.

Methods

A total of 162 consecutive patients with achalasia who had a laparoscopic myotomy and Dor fundoplication and who were available for follow-up interview were divided by age: <60 years (range, 14–59; 118 patients), and ≥60 years (range, 60–93; 44 patients). Primary outcome measures were severity of dysphagia, regurgitation, heartburn, and chest pain before and after the operation as assessed on a four-point Likert scale, and the need for postoperative dilatation or revisional surgery.

Results

Follow-up averaged 64 months. Older patients had less dysphagia (mean score 3.6 vs. 3.9; P < 0.01) and less chest pain (1.0 vs. 1.8; P < 0.01). Regurgitation (3.0 vs. 3.2; P = not significant (NS)) and heartburn (1.6 vs. 2.0, P = NS) were similar. Older patients were no different in degree of esophageal dilation, manometric findings, number of previous pneumatic dilatations, or previous botulinum toxin therapy. None of the older patients had previously had an esophagomyotomy, whereas 14% of younger patients had (P < 0.01).

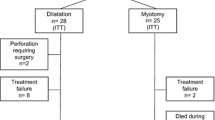

After laparoscopic myotomy, older patients had better relief of dysphagia (mean score 1.0 vs 1.6; P < 0.01), less heartburn (0.8 vs. 1.1; P = 0.03), and less chest pain (0.2 vs. 0.8, P < 0.01). Complication rates were similar. Older patients did not require more postoperative dilatations (22 patients vs. 10 patients; P = 0.7) or revisional surgery for recurrent or persistent symptoms (3 vs. 1 patients; P = 0.6). Satisfaction scores did not differ, and more than 90% of patients in both groups said in retrospect they would have undergone the procedure if they had known beforehand how it would turn out.

Conclusions

This retrospective review with long follow-up supports laparoscopic esophagomyotomy as first-line therapy in older patients with achalasia. They appeared to benefit even more than younger patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Esophageal achalasia is an uncommon esophageal motility disorder that presents with dysphagia and is characterized by absence of primary esophageal peristalsis and impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Although balloon dilatation and botulinum toxin injection can provide temporary benefit, only myotomy provides safe long-term relief of dysphagia [1–6]. We developed minimally invasive techniques for performing a Heller myotomy in 1991 [7] and switched from a thoracoscopic to a laparoscopic approach in 1994 [8]. The procedure gives predictably excellent results [3–5, 9–15], and at this point, most clinicians consider it to be first-line therapy [16, 17].

The safety and effectiveness of esophagomyotomy in elderly patients has been questioned, leading some gastroenterologists to favor balloon dilatation as the primary therapy in this group [18–21], whereas others prefer botulinum toxin [22]. Although our practice has been to offer esophagomyotomy as first-line therapy in fit patients regardless of age, there are scant data on the outcomes in this group. In this study we evaluated the safety and efficacy of laparoscopic esophagomyotomy in elderly patients.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the records of 270 consecutive patients who had a laparoscopic esophagomyotomy and Dor fundoplication for achalasia at the University of California, San Francisco from 1994–2009. In all patients, diagnosis was confirmed by esophageal manometry. An upper gastrointestinal series was performed to evaluate esophageal shape and diameter, and endoscopy was used to rule out malignant or peptic stricture of the gastroesophageal junction.

The following information was obtained for each patient: age, duration of symptoms, amount of weight loss, distal esophageal pressure during wet-swallows, LES resting pressure, LES relaxed pressure, esophageal diameter, and history of previous treatments for achalasia. The severity of preoperative and postoperative dysphagia, regurgitation, chest pain, and heartburn were retrospectively scored by the patients as follows: excellent (0 = no dysphagia, or 1 = only once or twice per month); good (2 = occasional dysphagia, once per week); fair (3 = frequent dysphagia, several times per week, often requiring dietary adjustments); poor (4 = severe daily dysphagia, often preventing ingestion of solid food).

Each patient had a laparoscopic esophagomyotomy and Dor fundoplication, which was performed as described previously [23]. Operative reports were reviewed, and the length of the myotomy, length of gastric extension, and type of fundoplication were recorded. Intraoperative and postoperative complications were recorded, including the need for postoperative dilatation or revisional surgery at any time within the follow-up period.

Patients were interviewed by telephone or mail questionnaire. Of the 270 patients who had an esophagomyotomy, follow-up was complete for 173 (64%). Eleven died from a cause unrelated to the operation, and 162 were interviewed. The severity of dysphagia, regurgitation, heartburn, and chest pain was reassessed on a four-point Likert scale. We inquired whether they had received additional treatment, such as endoscopic dilatation or another operation. Only patients who were available for follow-up were included.

The primary outcome measures were the severity of symptoms after the operation and the need for postoperative dilatation or revisional surgery. Categorical variables were compared between groups with Fisher’s exact test. Ordinal variables were compared with the Mann–Whitney test. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Of the 162 patients, 118 were younger than aged 60 years and 44 were aged 60 years or older. No differences were found for gender, race, clinical history, duration of symptoms, manometry findings, or esophageal diameter between groups (Table 1). Fourteen percent of patients younger than 60 years, but no patient 60 years or older had previously undergone an esophagomyotomy elsewhere (P < 0.01). Although all patients had dysphagia before the operation, the older group had less severe dysphagia and less chest pain (Table 1). Symptom scores for heartburn and regurgitation were similar between groups.

The myotomy extended at least 6 cm proximally from the gastroesophageal junction (Table 2). The extent of the myotomy onto the stomach changed during the study period. It was 1.0 cm early and increased to 1.5 cm in 2001. Almost all (97%) patients had a 180-degree Dor fundoplication to prevent postoperative gastroesophageal reflux. No deaths occurred within 30 days of the operation. Complications did not differ between the groups (Table 2), but half of them occurred in the first 50 cases.

Long-term outcomes are shown in Table 3. Mean follow-up for the entire cohort was 64 months and did not differ between groups. After the myotomy, older patients had less severe dysphagia, less heartburn, and less chest pain than did the younger patients. Regurgitation scores were similar. Overall, 32 patients required one or more postoperative dilatations, and 4 required another operation for recurrent or persistent dysphagia. Satisfaction scores for both groups were excellent, and >90% of patients in both groups reported they would undergo the procedure again.

With reoperative patients excluded from the analysis, all of whom were younger than aged 60 years, again older patients had better relief of dysphagia (mean score 1.0 vs. 1.6; P < 0.01), heartburn (0.8 vs. 1.1; P = 0.02), and chest pain (0.2 vs. 0.7; P < 0.01) than younger patients. Postoperative regurgitation was the same (0.7 vs. 0.7; P = NS). The number of patients who required postoperative dilatations (17 vs. 10 patients; P = 0.5) or reoperation (2 vs. 1; P = 0.5) also was similar.

Discussion

Achalasia is too uncommon to be studied by randomized comparisons of treatments. The literature on the subject is confined to retrospective series or small trials with limited statistical power. As a result, there are scant data on surgical outcomes in elderly patients with achalasia. In this study, we report our large series of esophagomyotomies performed during a 15-year period with a mean follow-up of more than 5 years. We found that older patients were similar to younger patients in disease severity at presentation, but they had better results after surgical esophagomyotomy.

Our findings differ from previous studies, which found that outcomes were the same or worse in older patients. No difference in outcome was found for 15 patients older than aged 70 years in a series of 31 patients [24], but patients with “severe” achalasia were excluded and the trial was underpowered. Likewise, no difference in outcome was found in 70 patients older than aged 60 years in a series of 407 patients [25]. In contrast, old age was the only univariate predictor of poor outcome in a series of 101 patients [26].

Some have suggested that older patients may seek treatment later and present with severe disease that is more difficult to palliate surgically. Our results do not support this. Older patients presented with a similar duration of symptoms, similar degree of esophageal dilation, and similar manometry findings when compared with younger patients. The only differences we found were that older patients reported less severe dysphagia and less chest pain, a finding observed by others [19, 27]. Furthermore, when older patients sought treatment, their dysphagia was reliably and safely treated with surgical esophagomyotomy. Satisfaction was excellent in both old and young patients, with >90% reporting they would undergo the same procedure again. Complication rates were not higher in older patients, and postoperative dysphagia, heartburn, and chest pain improved to a greater degree than in younger patients. Even with more advanced age, the results were excellent. None of our six patients who were older than aged 75 years at the time of myotomy required postoperative dilatation or reoperation, there were no complications, and all six said that they would undergo the operation again.

A potential confounder is the inclusion of 17 reoperative patients in the analysis, all of whom were in the younger age group. These patients may have different outcomes compared with patients without a previous myotomy. To ensure this was not a confounder, we removed the 17 reoperative patients and repeated the analysis; the results did not change.

The limitations of this study are its retrospective approach, our inability to completely follow-up all patients, and the lack of controls. Selection bias also may be a factor, because only patients fit for surgery were included. We do not know whether some older patients may have been considered unfit for surgery, never referred to our center, or treated nonoperatively. Finally, complications after esophagomyotomy are a rare event, so it is possible that our cohort of 44 patients older than aged 60 years would not be large enough to identify a subtle difference. Nevertheless, we have found minimally invasive esophagomyotomy to be well tolerated in most elderly patients. Two patients who were older than aged 90 years had excellent relief of dysphagia, now eat normally, and recovered without complications. We conclude that old age is not a contraindication for esophagomyotomy and Dor fundoplication in patients with achalasia.

References

Torquati A, Richards WO, Holzman MD, Sharp KW (2006) Laparoscopic myotomy for achalasia: predictors of successful outcome after 200 cases. Ann Surg 243:587–591 discussion 591–583

Khajanchee YS, Kanneganti S, Leatherwood AE, Hansen PD, Swanstrom LL (2005) Laparoscopic Heller myotomy with Toupet fundoplication: outcomes predictors in 121 consecutive patients. Arch Surg 140:827–833 discussion 833–824

Rosemurgy A, Villadolid D, Thometz D, Kalipersad C, Rakita S, Albrink M, Johnson M, Boyce W (2005) Laparoscopic Heller myotomy provides durable relief from achalasia and salvages failures after Botox or dilation. Ann Surg 241:725–733 discussion 733–725

Frantzides CT, Moore RE, Carlson MA, Madan AK, Zografakis JG, Keshavarzian A, Smith C (2004) Minimally invasive surgery for achalasia: a 10-year experience. J Gastrointest Surg 8:18–23

Oelschlager BK, Chang L, Pellegrini CA (2003) Improved outcome after extended gastric myotomy for achalasia. Arch Surg 138:490–495 discussion 495–497

Zaninotto G, Vergadoro V, Annese V, Costantini M, Costantino M, Molena D, Rizzetto C, Epifani M, Ruol A, Nicoletti L, Ancona E (2004) Botulinum toxin injection versus laparoscopic myotomy for the treatment of esophageal achalasia: economic analysis of a randomized trial. Surg Endosc 18:691–695

Patti MG, Arcerito M, Tong J, De Pinto M, de Bellis M, Wang A, Feo CV, Mulvihill SJ, Way LW (1997) Importance of preoperative and postoperative pH monitoring in patients with esophageal achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg 1:505–510

Patti MG, Arcerito M, De Pinto M, Feo CV, Tong J, Gantert W, Way LW (1998) Comparison of thoracoscopic and laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg 2:561–566

Campos GMVE, Rabl C, Takata M, Gadenstatter M, Lin F, Ciovica R (2009) Endoscopic and surgical treatments for achalasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 249:45–57

Shimi S, Nathanson LK, Cuschieri A (1991) Laparoscopic cardiomyotomy for achalasia. J R Coll Surg Edinb 36:152–154

Bonatti H, Hinder RA, Klocker J, Neuhauser B, Klaus A, Achem SR, de Vault K (2005) Long-term results of laparoscopic Heller myotomy with partial fundoplication for the treatment of achalasia. Am J Surg 190:874–878

Zaninotto G, Costantini M, Molena D, Buin F, Carta A, Nicoletti L, Ancona E (2000) Treatment of esophageal achalasia with laparoscopic Heller myotomy and Dor partial anterior fundoplication: prospective evaluation of 100 consecutive patients. J Gastrointest Surg 4:282–289

Patti MG, Fisichella PM, Perretta S, Galvani C, Gorodner MV, Robinson T, Way LW (2003) Impact of minimally invasive surgery on the treatment of esophageal achalasia: a decade of change. J Am Coll Surg 196:698–703 discussion 703–695

Patti MG, Tamburini A, Pellegrini CA (1999) Cardiomyotomy. Semin Laparosc Surg 6:186–193

Ackroyd R, Watson DI, Devitt PG, Jamieson GG (2001) Laparoscopic cardiomyotomy and anterior partial fundoplication for achalasia. Surg Endosc 15:683–686

Leyden JE, Moss AC, MacMathuna P (2006) Endoscopic pneumatic dilation versus botulinum toxin injection in the management of primary achalasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 18(4):CD005046

Spiess AE, Kahrilas PJ (1998) Treating achalasia: from whalebone to laparoscope. JAMA 280:638–642

Robertson CS, Fellows IW, Mayberry JF, Atkinson M (1988) Choice of therapy for achalasia in relation to age. Digestion 40:244–250

Simmons DB, Schuman BM, Griffin JW Jr (1997) Achalasia in patients over 65. J Fla Med Assoc 84:101–103

Dobrucali A, Erzin Y, Tuncer M, Dirican A (2004) Long-term results of graded pneumatic dilatation under endoscopic guidance in patients with primary esophageal achalasia. World J Gastroenterol 10:3322–3327

Boztas G, Mungan Z, Ozdil S, Akyuz F, Karaca C, Demir K, Kaymakoglu S, Besisik F, Cakaloglu Y, Okten A (2005) Pneumatic balloon dilatation in primary achalasia: the long-term follow-up results. Hepatogastroenterology 52:475–480

Bruley des Varannes S, Scarpignato C (2001) Current trends in the management of achalasia. Dig Liver Dis 33:266–277

Patti MG (2007) Minimally invasive esophageal procedures. In: ACS surgery principles and practice, 6th edn. BC Decker, Philadelphia, PA, pp 378–392

Ferulano GP, Dilillo S, D’Ambra M, Lionetti R, Brunaccino R, Fico D, Pelaggi D (2007) Short and long-term results of the laparoscopic Heller-Dor myotomy. The influence of age and previous conservative therapies. Surg Endosc 21:2017–2023

Zaninotto G, Costantini M, Rizzetto C, Zanatta L, Guirroli E, Portale G, Nicoletti L, Cavallin F, Battaglia G, Ruol A, Ancona E (2008) Four hundred laparoscopic myotomies for esophageal achalasia: a single-center experience. Ann Surg 248:986–993

Rosen MJ, Novitsky YW, Cobb WS, Kercher KW, Heniford BT (2007) Laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia in 101 patients: can successful symptomatic outcomes be predicted? Surg Innov 14:177–183

Rakita S, Bloomston M, Villadolid D, Thometz D, Boe B, Rosemurgy A (2005) Age affects presenting symptoms of achalasia and outcomes after myotomy. Am Surg 71:424–429

Acknowledgments

Presented at the 2009 meeting of the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) Surgical Spring Week, April 22–25, 2009. This work was not supported by any outside research funding.

Disclosures

Drs. Roll, Gasper, Patti, Way, and Carter and Ms. Ma have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Roll, G.R., Ma, S., Gasper, W.J. et al. Excellent outcomes of laparoscopic esophagomyotomy for achalasia in patients older than 60 years of age. Surg Endosc 24, 2562–2566 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1003-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1003-4