Abstract

Background

Many laparoscopic simulation training systems exist and have been shown to transfer learning of surgical skills to the operating room. The manner in which the training is structured to maximize learning has not been examined. There are many aspects to the acquisition of laparoscopic skills during training, one of which is the availability of knowledge of results (KR). Knowledge of results is information about the outcome of motor skill execution, usually provided to individuals at the end of the execution. The timing and nature of KR can affect how well people learn new motor skills. In addition, detailed instruction during learning can also affect skill acquisition. We studied the effects of KR and instruction on the learning curve of a suturing and knot-tying task. We hypothesized that KR was necessary for skill acquisition, and that detailed instruction would help trainees to learn to perform the task more correctly and reach a performance plateau earlier. In addition, the overall workload of a trainee during training would decrease as skills improved, especially when KR and coaching were provided.

Methods

Nine medical students with no previous laparoscopic surgical experience were randomly and evenly divided into three groups with different KR conditions: (1) no KR, (2) KR, (3) KR + instruction. Each subject attended a training session for 1 h each day, 6 days a week for 4 consecutive weeks. Performance measures such as task time, smoothness of instrument, and path length were recorded for each trial. Workload was assessed using the NASA-TLX questionnaire.

Results

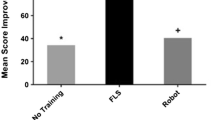

While KR was necessary for learning to suture, continual instruction had limited additional benefits. However, KR + instruction did reduce subjects’ perceived overall workload.

Conclusions

Surgical training could be carried out effectively with only knowledge of results. These results have implications for the staffing of surgical skills laboratories.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Berguer R, Smith WD, Chung Y-H (2001) Performing laparoscopic surgery is significantly more stressful for the surgeon than open surgery. Surg Endosc 15:1027–1029

Bridges M, Diamond DI (1999) The financial impact of teaching surgical residents in the operating room. Am J Surg 117(1):28–32

Cuschieri A (2005) Laparoscopic surgery: current status, issues and future developments. Surgeon 3:125–130,132–133, 135–138

Hanssona GA, Arvidssona I, Ohelssona K, Nordandera C, Mathiassenb SE, Skerfvinga S, Balogha I (2006) Precision of measurements of physical workload during standardised manual handling. Part II: inclinometry of head, upper back, neck and upper arms. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 16:125–136

Hart SG, Staveland LE (1988) Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): results of empirical and theoretical research. In: Hancock PA, Meshkati N (eds), Human Mental Workload. Amsterdam: Elsevier-North Holland, pp. 139–183

Long KH, Bannon MP, Zietlow SG, Helgeson ER, Harmsen WS, Smith CD, Ilsatrup DM, Baerga-Varela Y, Sarr MG (2001) Laparoscopic Appendectomy Interest Group. A prospective randomized comparison of laparoscopic appendectomy with open appendectomy: clinical and economic analyses. Surgery l29:390–400

Mahmood T, Darzi A (2004) The learning curve for a colonoscopy simulator in the absence of any feedback, no feedback, no learning. Surg Endosc 18:1224–1230

Park ADW, Witzke D, Donnelly M (2002) Ongoing deficits in resident training for minimally invasive surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 6:501–509

Rogers DA, Regehr G, Howdieshell TR, Yeh KA, Palm E (2000) The impact of external feedback on computer-assisted learning for surgical technical skill training. Am J Surg 179:341–343

Schmidt RA, Timothy D. Lee (2005) Motor Control and Learning: A Behavioural Emphasis, 4th Edition. Champaign, IL, Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc., p 535

Scott DJ, Bergen PC, Rege RV, Laycock R, Tesfay ST, Valentine RJ, Euhus DM, Jeyarajah DR, Thompson WM, Jones DB (2000) Laparoscopic training on bench models: better and more cost effective than operating room experience? J Am Coll Surg 191:272–283

Seymour NGA, Roman S, O’Brien M, Bansal VK, Andersen DK, Satava RM (2002) Virtual reality training improves operating room performance: results of a randomized, double-blinded study. Ann Surg 236:458–463

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Connor, A., Schwaitzberg, S.D. & Cao, C.G.L. How much feedback is necessary for learning to suture?. Surg Endosc 22, 1614–1619 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-007-9645-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-007-9645-6