Abstract

Research on the bioavailability of water from thickened fluids has recently been published and it concluded that the addition of certain thickening agents (namely, modified maize starch, guar gum, and xanthan gum) does not significantly alter the absorption of water from the healthy, mature human gut. Using xanthan gum as an example, our “proof of concept” study describes a simple, accurate, and noninvasive alternative to the methodology used in that first study, and involves the measurement and comparison of the dilution space ratios of the isotopes 2H and 18O and subsequent calculation of total body water. Our method involves the ingestion of a thickening agent labeled with 2H 1 day after ingestion of 18O. Analyses are based on the isotopic enrichment of urine samples collected prior to the administration of each isotope, and daily urine samples collected for 15 days postdosing. We urge that further research is needed to evaluate the impact of various thickening agents on the bioavailability of water from the developing gut and in cases of gut pathology and recommend our methodology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Health professionals working in feeding/swallowing clinics frequently recommend the use of thickening agents for therapeutic purposes with both adult and pediatric caseloads. Within the pediatric population, thickened fluids are often recommended by health professionals for two main groups of patients: (1) children at risk of aspirating regular (i.e., thin) fluids into their airway, and (2) those children who display regurgitation. The rationale behind thickening fluids is to assist with the safe swallowing of fluids and/or to reduce the regurgitation of feeds, thereby optimising nutritional status and, it is assumed, preventing dehydration. However, little information is currently available regarding the bioavailability of water from thickened fluids.

The issue of hydration is of particular importance when managing pediatric patients. Fluid, in the form of infant formula or breast milk, is an infant’s sole source of nutrition until approximately 6 months, and a large part of their diet until approximately 12 months. Therefore, any reduction in the availability of water from fluid feeds could not be compensated for by water from solid food types. In addition, due to the nature of their disorder, patients with dysphagia and/or regurgitation may have more difficulty consuming their daily fluid intake requirements than the general population [1]. Any irreversible binding of water by thickening agents would have the potential to exacerbate this problem by limiting the water available from any fluid that is consumed. This would have the potential to lead to dehydration and associated problems. Furthermore, poor fluid availability may have the potential to make any feeding problems in this population worse, as constipation, a common symptom of dehydration, may result in reduced hunger, irritability and behavioral issues [2].

Sharpe et al. [3] recently produced the first (and, to our knowledge, only) published research on the issue of bioavailability of water from thickened fluids. Sharpe et al. [3] developed a novel method for testing the bioavailability of water from thickened fluids. Specifically, the investigators provided participants with repeated test samples of water containing bromide and deuterium oxide (2H2O) mixed with various thickening agents (namely, modified maize starch, guar gum, and xanthan gum) for consumption. Participants were required to give a 5-ml blood sample before being dosed with each test fluid and at 240 min postdosing. In addition, saliva samples were taken before dosing and at 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, and 240 min postdosing. The investigators also tested participants’ bioelectrical impedance pre- and postconsumption of thickened fluids. They concluded that the addition of certain commonly used thickening agents did not significantly alter the absorption rate of water from the healthy, mature human gut.

This article is a “proof of concept” study that details a simple method for assessing the bioavailability of water when mixed with fluid thickeners that is more accurate and less invasive than that proposed by Sharpe et al. [3]. For the purpose of illustrating our method, we have used a fluid thickened with xanthan gum and administered to a single subject as a case study.

Methods

Procedure

Total body water (TBW) was measured on two consecutive days using stable, nonradioactive, nontoxic isotopes. For the first measurement of TBW, the participant was given an oral dose of an isotope of oxygen (O18), in the form of water (H 182 O). The subject consumed 1.5 g/kg body weight of 4% H 182 O via a syringe to minimise residue. The dose consumed was recorded to the nearest 10 mg. A single urine sample was obtained before the dose and subsequent urine samples were collected 4–6 h postdose and then once every 24 h (approximately) for the following 15 days. The subject recorded the time each urine sample was collected.

At the same time the following day, TBW was again measured using an isotope of hydrogen (2H) in the form of water (2H2O, deuterium oxide). The subject consumed via a syringe 0.05 g/kg body weight of 99.9% deuterium oxide mixed into a sample of 50 ml tap water plus a xanthan gum fluid thickener (EasyThick, Flavour Creations). Xanthan gum was chosen for the purpose of illustrating our novel stable isotope method because it is a commonly used fluid thickener, and it was one of thickening agents tested by Sharpe et al. [3]. Other thickening agents may be substituted for labeling with 2H, and the 2H could be added to sample fluids other than tap water (e.g., juice, cordial, milk, infant formula). The solution was thickened according to the manufacturer’s instructions to produce a solution thickened to full (pudding) thick. The dose was recorded to the nearest 10 mg. A single urine sample was obtained before the dose and 4–6 h postdose. The daily urine samples collected for 18O analysis were also used for 2H analysis. All urine samples were frozen until analysis. It was not necessary to place predose restrictions on the participant with respect to food or drink consumption on either of the testing days, as this method yields an average result from the collection of multiple urine samples over a 2-week period. In addition, the isotopic enrichment of each postdose sample is analysed with respect to the predose urine sample; this effectively serves as a control. Therefore, unlike methods that measure the rate of appearance of isotopes in bodily fluid, this method is not affected by short-term differences in gastric emptying or intestinal absorption rates in relation to prior food or beverage consumption.

To determine each dilution space and measure TBW, the enrichment of 2H and 18O in the predose and postdose urine samples, the dose administered, and the local tap water were assessed via isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) (PDZ Europa, UK).

To measure the enrichment of 2H, 0.5 ml of each urine sample was pipetted into a 12-ml vacuutainer. A catalyst, approximately 1 mg of platinum on alumina powder (Sigma Aldrich) contained in a 0.5-ml vial (Hewlett Packard Pty), was introduced into the vacuutainer while ensuring no direct contact of the catalyst and the urine. Each vacuutainer was evacuated for a period of 5 min before being filled with 99% hydrogen gas. The vaccutainers were then kept at room temperature for 3 days to allow the 2H in the sample to achieve equilibrium with the hydrogen gas [4]. All reference waters were prepared at the same time and in the same manner as the urine samples.

Similarly, to measure the enrichment of 18O, 0.5 ml of each urine sample were pipetted into a 12-ml vacuutainer. The vacuutainers were then evacuated for 5 minutes, and 5% carbon dioxide, 95% nitrogen gas was introduced into the vacuutainer. The samples were then kept at room temperature for 24 h to facilitate the equilibrium between the 18O in the sample and the gas. Again, reference waters were prepared at the same time and in the same manner as the urine samples.

The enrichment of both the 2H and 18O samples were measured in duplicate with the results being expressed in delta units as ‰ (per mil) relative to standard mean ocean water (SMOW).

The theoretical instantaneous enrichments of body water, which could be obtained by the administered dose and defined as the intercept obtained by back-extrapolation of the semilogarithmic plot of observed enrichment against time, is given by a rearrangement of the equation of Halliday and Miller [5] as

for deuterium, and

for 18O. In these equations, A is the mass of the isotope administered to the subject (in g), a is the mass of the dose retained and diluted in T litres of tap water for IRMS analysis, with the subscripts D for deuterium and O for 18O, respectively. E aD and E aO are the enrichments of deuterium and 18O in the dilute dose, and E tD and E tO are those of the tap water. The factors of 1.04 and 1.01 are correction factors to relate isotope dilution space to total body water (TBW) [6], and are introduced to account for exchange with sites of nonaqueous species. Finally, we have explicitly included in this equation bioavailability factors F D and F O. For pure water these would be taken as unity (i.e., F O = 1); however, if it is the case that the thickening agent reduces the degree to which water can be absorbed, then F D would be found to be less than 1. F D can be calculated by combining the two equations:

Participant

A single participant (PMMD) volunteered for the purposes of testing. Informed consent was obtained from the participant.

Results

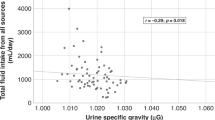

The age of the subject was 25 years, height 181 cm, and weight 64 kg. The complete set of isotope data recorded for this subject is given in Table 1. The estimated oxygen distribution space was 523 mg/kg, yielding an estimated TBW of 518 ml/kg, which is in the well-documented physiologic range. The bioavailability of water from the thickened fluid was 0.97 ± 0.06 (mean ± standard error), suggesting that the xanthan gum fluid thickener was not binding the deuterium [i.e., water (2H2O)] with which it was mixed, and, therefore, the bioavailability of the water in the solution was unaffected by the addition of the thickening agent.

Discussion

Sharpe et al. [3] described a method to determine the influence of thickening agents on the absorption of water. Our short report is a “proof of concept” study aimed at detailing a more accurate, less invasive approach to that proposed by Sharpe et al. [3], involving isotopically labeling a thickened fluid to assess the bioavailability of water when mixed with a thickening agent.

The approach discussed by Sharpe et al. [3] involved assessing water absorption by labeling a thickened fluid with 2H and measuring the rate of appearance of 2H in saliva and blood samples. In addition, the thickened fluid was also labeled with sodium bromide to determine the extracellular water space, and bioelectrical impedance (BIA) was used to measure TBW. While (similar to our methods) this method involves the oral ingestion of a labeled thickened fluid and, thus, allows assessment in a physiologically “real” environment, it is nevertheless associated with several problems. First, it is difficult to ensure that residual amounts of the isotopic tracer labeling an orally ingested fluid do not remain in the mouth and, therefore, alter the enrichment of saliva samples. While attempts were made by the authors to minimise this potential source of error, saliva samples are less than ideal in these circumstances, unless alternative methods are used to label the fluid [7]. Second, this method looks at the rate of appearance of 2H over a short time and, thus, is more susceptible to the confounding effects of diuretics and pretest food consumption, particularly with respect to gastric emptying and intestinal absorption rates. Third, while BIA is an inexpensive, noninvasive, and reliable method of measuring TBW, it is not always accurate [8], especially in comparison to the isotope techniques utilised in our methodology. In addition, Sharpe et al. also collected blood samples for comparison with the results of the saliva samples. This sample collection method is limited as it is an invasive procedure that is not well tolerated by some individuals. Finally, adding sodium bromide to an orally ingested fluid may not be palatable because it has a strong salty taste and thus its use may be limited in certain populations, such as children.

We, therefore, believe our methodology to be more accurate and less invasive than that of Sharpe et al. [3]. 2H and 18O are stable, nonradioactive, nontoxic isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen, respectively. They are ingested in the form of water (2H2O and H 182 O) and, therefore, taste similar to ordinary tap water. Samples are collected via urine and, therefore, there are no contamination issues related to residual amounts of tracer remaining in the oral cavity, as with saliva samples. Urine samples are easily collected from subjects of any age (from preterm infants to the elderly) and, when required, may be collected via cotton balls placed in a diaper; catheterisation is not necessary due to the small volumes of urine needed (approximately 2 ml). Urine samples are easy to work with for analysis and our method is noninvasive for the subject. Finally, stable isotope techniques are associated with good accuracy and precision [9] and are considered the gold standard for the measurement of TBW.

However, a limitation of our method is the relative expense of the 18O isotope. At the time of publication, it would cost approximately 105 $US to dose a 60-kg adult with the amount of 18O used in our study. While improvements in isotope ratio mass spectrometry allow smaller and smaller dosages to be used, it is still a relatively expensive way to measure TBW, compared with either 2H or other techniques like BIA. However, while relatively expensive, the accuracy of isotope labeling is a major benefit of this technique.

The results presented here indicate that the thickening agent tested does not alter the apparent bioavailability of water. Obviously, our single-subject, single-thickened-fluid example was used to describe the novel method we propose rather than prove the effect of this thickening agent on the bioavailability of water per se. There are many thickening agents available on the market for patient use, and we believe that it is important that they are all tested to determine their impact on the bioavailability of the water in fluids with which they are mixed. Specifically, it cannot be assumed that different thickening agents will interact in the same way with a fluid, or indeed that the same thickening agent will interact in the same way with different fluids (e.g., water-based fluids vs. nutrient-dense milk-based fluids) [10]. Therefore, it is essential that different combinations of fluids and thickening agents offered to patients are tested to determine the bioavailability of water from different thickened fluids. We recommend our methodology as being both an accurate and minimally invasive way to do so.

A further question that needs to be investigated is whether certain individuals may be more or less effective at digesting thickening agents and, thus, altering the availability of water from thickened fluids. Interestingly, Sharpe et al. [3] reported intersubject variation in the rate of water uptake in their healthy, nonclinical sample group, which may be indicative of this phenomenon. Further research with greater numbers of participants is needed to investigate this possibility. In particular, attention needs to be given to the effect of gut pathology and/or the interference of medication such as histamine-2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors, on the digestion of various thickening agents. This is especially so, given that many patients are initiated on thickening agents in an attempt to manage the symptoms of regurgitation and, therefore, will almost certainly have some degree of gut pathology and/or be exposed to acid suppression medications. Many dysphagic patients who use thickened fluids as a way to minimise aspiration during swallowing may also have a coinciding gut pathology [11].

This study detailed a novel method for investigating the bioavailability of water when mixed with thickening agents. Another separate but equally important issue that merits further investigation is the bioavailability of nutrients from thickened fluids. Several in vitro studies have suggested that a variable proportion of certain micronutrients can become irreversibly bound to some types of thickening agents and, thus, be rendered unavailable for digestion [12–14]. Clearly, if confirmed, this would have implications for the use of certain thickening agents with nutrition-providing liquids (e.g., infant formula, nutritional supplement drinks). However, if the proportional bioavailability of nutrients could be calculated, additional volumes of the nutrients could be provided to allow for some irreversible binding to the thickening agent.

Conclusion

This “proof of concept” study describes a novel approach for determining the bioavailability of the water from thickened fluids, involving the measurement of the dilution space ratios of the isotopes 2H and 18O. Using xanthan gum as the thickening agent and a single subject, we have shown that our method is simple, noninvasive, and accurate. We recommend that further testing is required with larger participant numbers, other thickening agents, and a variety of fluids with which thickeners are commonly mixed. We believe that it is important that all thickening agents recommended for patient use be tested to determine their impact on the bioavailability of the water in the fluids with which they are mixed and recommend our methodology as currently being the most accurate and least invasive.

References

Leibovitz A, Baumoehl Y, Lubart E, Yaina A, Platinovitz N, Segal R. Dehydration among long-term care elderly patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gerontology. 2007;53(4):179–83. doi:10.1159/000099144.

Baker SS, Liptak GS, Colletti RB, Croffie JM, Di Lorenzo C, Ector W, et al. Constipation in infants and children: evaluation and treatment. A medical position statement of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;29:612–26. doi:10.1097/00005176-199911000-00029.

Sharpe K, Ward L, Cichero J, Sopade P, Halley P. Thickened fluids and water absorption in rats and humans. Dysphagia. 2007;22(3):193–203. doi:10.1007/s00455-006-9072-1.

Prosser SJ, Scrimgeour CM. High precision determination of 2H/1H in H2 and H2O by continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1995;67:1992–7. doi:10.1021/ac00109a014.

Halliday D, Miller AG. Precise measurement of total body water using trace quantities of deuterium oxide. Biomed Mass Spectrom. 1977;4:82–9. doi:10.1002/bms.1200040205.

Coward WA, Cole TJ. The doubly labelled water methods for the measurement of energy expenditure in humans: risks and benefits. In: Whitehead RG, Prentice A, editors. New Techniques in Nutritional Research. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1993. p. 139–76.

Hill RJ, Bluck LJC, Davies PSW. Using a non-invasive stable isotope tracer to measure the absorption of water in humans. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:701–6. doi:10.1002/rcm.1391.

Bell NA, McClure PD, Hill RJ, Davies PS. Assessment of foot-to-foot bioelectrical impedance analysis for the prediction of total body water. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52:856–9. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600661.

Schoeller DA, van Santen E, Peterson DW, Dietz W, Jaspan J, Klein PD. Total body water measurement in humans with 18O and 2H labeled water. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980;33:2686–92.

Garcia JM, Chambers E IV, Matta Z, Clark M. Viscosity measurements of nectar- and honey-thick liquids: product, liquid, and time comparisons. Dysphagia. 2005;20(4):325–35. doi:10.1007/s00455-005-0034-9.

Burklow KA, Phelps AN, Schultz JR, McConnell K, Rudolph C. Classifying complex pediatric feeding disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27(2):143–7. doi:10.1097/00005176-199808000-00003.

Bosscher D, Van Caillie-Bertrand M, Deelstra H. Do thickening properties of locust bean gum affect the amount of calcium, iron and zinc available for absorption from infant formula? In vitro studies. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2003;54(4):261–8. doi:10.1080/09637480120092080.

Bosscher D, Van Caillie-Bertrand M, Deelstra H. Effect of thickening agents, based on soluble dietary fiber, on the availability of calcium, iron, and zinc from infant formulas. Nutrition. 2001;17(7–8):614–8. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(01)00541-X.

Bosscher D, Van Caillie-Bertrand M, Van Dyck K, Robberecht H, Van Cauwenbergh R, Deelstra H. Thickening infant formula with digestible and indigestible carbohydrate: availability of calcium, iron, and zinc in vitro. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30(4):373–8. doi:10.1097/00005176-200004000-00005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hill, R.J., Dodrill, P., Bluck, L.J.C. et al. A Novel Stable Isotope Approach for Determining the Impact of Thickening Agents on Water Absorption. Dysphagia 25, 1–5 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-009-9221-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-009-9221-4