Abstract

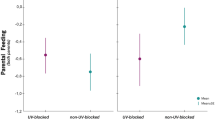

Carotenoid-based colours are widespread in animals and are used as signals in intra- and interspecific communication. In nestling birds, the carotenoids used for feather pigmentation may derive via three pathways: (1) via maternal transfer to egg yolk; (2) via paternal feeds early after hatching when females are mainly brooding; or (3) via feeds from both parents later in nestling life. We analysed the relative importance of the proposed carotenoid sources in a field experiment on great tit nestlings (Parus major). In a within-brood design we supplemented nestlings with carotenoids shortly after hatching, later on in the nestling life, or with a placebo. We show that the carotenoid-based colour expression of nestlings is modified maximally during the first 6 days after hatching. It reveals that the observed variation in carotenoid-based coloration is based only on mechanisms acting during a short period of time in early nestling life. The experiment further suggests that paternally derived carotenoids are the most important determinants of nestling plumage colour.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bakker TCM, Mundwiler B (1994) Female mate choice and male red coloration in a natural three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) population. Behav Ecol 5:74–80

Beath K (2000) GLM Stat version 5.2.1. Available from http://members.ozemail.com.au/~kjbeath/glmstat.html

Bendich A (1989) Carotenoids and the immune response. J Nutr 119:112–115

Bendich A (1991) β-carotene and the immune response. Proc Nutr Soc 50:263–274

Bennett ATD, Cuthill IC, Norris KJ (1994) Sexual selection and the mismeasure of color. Am Nat 144:848–860

Betts MM (1955) The behaviour of a pair of great tits at the nest. Br Birds 48:77–82

Blount JD, Houston DC, Møller AP (2000) Why egg yolk is yellow. Trends Ecol Evol 15:47–49

Brawner WR, Hill GE, Sundermann CA (2000) Effects of coccidial and mycoplasmal infections on carotenoid-based plumage pigmentation in male house finches. Auk 117:952–963

Brush AH (1990) Metabolism of carotenoid pigments in birds. FASEB J 4:2969–2977

Burton GW (1989) Antioxidant action of carotenoids. J Nutr 119:109–111

Cuthill IC, Partridge JC, Bennett ATD, Church SC, Hart NS, Hunt S (2000) Ultraviolet vision in birds. Adv Stud Behav 29:159–214

Dufva R, Allander K (1995) Intraspecific variation in plumage coloration reflects immune response in great tits (Parus major) males. Funct Ecol 9:785–789

Fitze PS, Richner H (2002) Differential effects of a parasite on ornamental structures based on melanins and carotenoids. Behav Ecol 13:401–407

Fitze PS, Koelliker M, Richner H (2003) Effects of common origin and common environment on nestling plumage coloration in the great tit (Parus major). Evolution 57:144–150

Frischknecht M (1993) The breeding colouration of male three-spined sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) as an indicator of energy investment in vigour. Evol Ecol 7:439–450

Gosler S (1993) The great tit. Hamlyn, London

Götmark F, Hohlfalt A (1995) Bright male plumage and predation risk in passerine birds: are males easier to detect than females? Oikos 74:475–484

Grether GF, Hudon J, Millie DF (1999) Carotenoid limitation of sexual coloration along an environmental gradient in guppies. Proc R Soc Lond B 266:1317–1322

Hamilton WD, Zuk M (1982) Heritable true fitness and bright birds: a role for parasites? Science 218:384–387

Hill GE (1990) Female house finches prefer colourful males: sexual selection for a condition-dependent trait. Anim Behav 40:563–572

Hill GE (1991) Plumage coloration is a sexually selected indicator of male quality. Nature 350:337–339

Hill GE (1992) Proximate basis of variation in carotenoid pigmentation in male house finches. Auk 109:1–12

Hill GE (1994) Geographic variation in male ornamentation and female mate preference in the house finch: a comparative test of models of sexual selection. Behav Ecol 5:64–73

Hill GE, Brawner III WR (1998) Melanin-based plumage coloration in the house finch is unaffected by coccidial infection. Proc R Soc Lond B 265:1105–1109

Hōrak P, Vellau H, Ots 1, Moller AP (2000) Growth conditions affect carotenoid-based plumage coloration of great tit nestlings. Naturwissenschaften 87:460–464

Hōrak P, Ots I, Vellau H, Spottiswoode C, Møller AP (2001) Carotenoid-based plumage coloration reflects hemoparasite infection and local survival in breeding great tits. Oecologia 126:166–173

Kluijver HN (1950) Daily routines of the great tit, Parus m. major L. Ardea 38:99–135

Kodric-Brown A (1989) Dietary carotenoids and male mating success in the guppy: an environmental component to female choice. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 25:393–401

Linville SU, Breitwisch R, Schilling AJ (1998) Plumage brightness as an indicator of parental care in northern cardinals. Anim Behav 55:119–127

Mertens JAL (1977) Thermal conditions for successful breeding in great tits (Parus major L.). Oecologia 28:1-29

Milinski M, Bakker TCM (1990) Female sticklebacks use male coloration in mate choice—and hence avoid parasitized males. Nature 344:330–333

Nys Y (2000) Dietary carotenoids and egg yolk coloration: a review. Arch Gefluegelkd 64:45–54

Olson VA, Owens IPF (1998) Costly sexual signals: are carotenoids rare, risky or required? Trends Ecol Evol 13:510–514

Partali V, Liaaen-Jensen S, Slagsvold T, Lifjeld JT (1987) Carotenoids in food chain studies II. The food chain of Parus spp. monitored by carotenoid analysis. Comp Biochem Physiol B 82B:767–772

Royama T (1966) Factors governing feeding rate, food requirement and brood size of nestling great tits Parus major. Ibis 108:313–347

Sall J, Lehman A (1996) JMP start statistics. Duxbury Press, New York

Schantz T von, Bensch S, Grahn M, Hasselquist D, Wittzell H (1999) Good genes, oxidative stress and condition-dependent sexual signals. Proc R Soc Lond B 266:1-12

Senar JC, Figuerola J, Pascual J (2002) Brighter yellow blue tits make better parents. Proc R Soc Lond B 269:257–261

Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ (1981) Biometry. Freeman, New York

Surai PF, Speake BK, Noble RC, Sparks NHC (1999) Tissue-specific antioxidant profiles and susceptibility to lipid peroxidation of the newly hatched chick. Biol Trace Elem Res 68:63–78

Svensson L (1992) Identification guide to European passerines. Heraclio Fournier, Stockholm, Sweden

Thompson CW, Hillgarth N, Leu M, McClure HE (1997) High parasite load in house finches (Carpodacus mexicanus) is correlated with reduced expression of a sexually selected trait. Am Nat 149:270–294

Tschirren B, Fitze PS, Richner H (2003) Proximate mechanisms of variation in the carotenoid-based plumage coloration of nestling great tits (Parus major L.). J Evol Biol 16:91–100

Winkel W (1970) Hinweise zur Art- und Altersbestimmung von Nestlingen höhlenbrütender Vogelarten anhand ihrer Körperentwicklung. Vogelwelt 91:52–59

Acknowledgements

We thank Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel and Alfred Giger for kindly providing carotenoid and placebo beadlets, Kurt Bernhard for helpful advice, and Jean-Daniel Charrière and Peter Fluri for providing the bee larvae. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 31-53956.98 to H. Richner) and the Swiss Bundesamt für Bildung und Wissenschaft (grant BBW Nr. 01.0254 to P.S. Fitze). The experiment was conducted under a licence provided by the Ethical Committee of the Office of Agriculture of the Canton of Bern, Switzerland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fitze, P.S., Tschirren, B. & Richner, H. Carotenoid-based colour expression is determined early in nestling life. Oecologia 137, 148–152 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-003-1323-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-003-1323-3