Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is caused by a nonsense or frameshift mutation in the DMD gene, while its milder form, Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) is caused by an in-frame deletion/duplication or a missense mutation. Interestingly, however, some patients with a nonsense mutation exhibit BMD phenotype, which is mostly attributed to the skipping of the exon containing the nonsense mutation, resulting in in-frame deletion. This study aims to find BMD cases with nonsense/frameshift mutations in DMD and to investigate the exon skipping rate of those nonsense/frameshift mutations. We searched for BMD cases with nonsense/frameshift mutations in DMD in the Japanese Registry of Muscular Dystrophy. For each DMD mutation identified, we constructed minigene plasmids containing one exon with/without a mutation and its flanking intronic sequence. We then introduced them into HeLa cells and measured the skipping rate of transcripts of the minigene by RT-qPCR. We found 363 cases with a nonsense/frameshift mutation in DMD gene from a total of 1497 dystrophinopathy cases in the registry. Among them, 14 had BMD phenotype. Exon skipping rates were well correlated with presence or absence of dystrophin, suggesting that 5% exon skipping rate is critical for the presence of dystrophin in the sarcolemma, leading to milder phenotypes. Accurate quantification of the skipping rate is important in understanding the exact functions of the nonsense/frameshift mutations in DMD and for interpreting the phenotypes of the BMD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dystrophinopathy is a group of progressive neuromuscular diseases caused by mutations in DMD (OMIM 300,377) located at Xp21.2. In male patients, a nonsense or frameshift mutation in the DMD gene cause a severe phenotype, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD; OMIM 310,200), while in-frame deletion/duplication or missense mutation result in a milder phenotype, Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD; OMIM 300,376) (Monaco et al. 1988). Interestingly, however, some patients with a nonsense mutation or out-of-frame deletion/duplication of certain exons have been reported to show BMD phenotypes. In former cases, BMD phenotype is mostly attributed to the skipping of the exon containing the nonsense mutation, resulting in in-frame deletion (Shiga et al. 1997; Tuffery-Giraud et al. 2005), while in latter cases, variable splicing was caused around the genomic deletion, leading to restore the in-frame products (Anthony et al. 2014; Beggs et al. 1991; Deburgrave et al 2007; Kesari et al. 2008; Sherratt et al. 1993; Winnard et al. 1993; Tuffery-Giraud et al. 2017). For six nonsense mutations, the mechanism has been hypothesized as the point mutations resulting in either the critical disruption of exonic splicing enhancer (ESE) or creation of exonic splicing suppressor (ESS) motifs (Shiga et al. 1997; Disset et al. 2006; Kevin et al. 2011; Nishida et al. 2011). Furthermore, it also has been proposed that the effects of these single point mutations are dependent on weak intrinsic exon definition elements (Kevin et al. 2011). These exon skipping events by nonsense mutations are not specific to skeletal muscle, and they will be responsible for milder phenotype of not only skeletal muscle but also other organs in the patients. The minigene assay could be performed in HeLa cells as in previous reports (Nishida et al. 2011; Zhu et al. 2019). To understand these events and to simply evaluate the nonsense/frameshift mutations on the skipping rate of the corresponding exon, we analyzed exon skipping caused by the nonsense/frameshift mutations from a Japanese large cohort in artificial minigene experiments (Okubo et al. 2016, 2017).

Methods

Registry-based datasets

The Japanese Registry of Muscular Dystrophy (Remudy) was developed in 2009 in collaboration with the Translational Research in Europe-Assessment and Treatment of Neuromuscular Diseases (TREAT-NMD) Network of Excellence (Gatta et al. 2005; Lalic et al. 2005; Todorova et al. 2008). The Remudy database for male patients with dystrophinopathy includes clinical and molecular genetic data, as well as all mandatory and highly encouraged items for the TREAT-NMD global patient registry (Nakamura et al. 2013). All data were collected using the registrant’s self-report after obtaining the physician’s confirmation. Patient phenotypes were classified into three subgroups, DMD, intermediate muscular dystrophy (IMD), and BMD, based on the age at loss of ambulation [DMD < 13 years, 13 years ≤ IMD ≤ 16 years, and 16 years < BMD (Tuffery-Giraud et al. 2009)] and the results of dystrophin immunostaining in muscles. Genetic curators then independently evaluated the genetic data (Okubo et al. 2016). Pathological data (including dystrophin immunostaining, where applicable) were reviewed by clinical and genetic curators independently. In the present study, we used the registry data compiled from July 2009 to March 2017.

Isolation of RNA from muscle biopsy and analysis of DMD transcripts

Total RNA was extracted from the muscle of patients by RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Reverse transcription reaction was performed as previously described (Nishida et al. 2011). Primers used for amplification of dystrophin mRNAs are shown in Supplementary Table S1. PCR products were analyzed on 2% agarose gels in Tris–borate/EDTA buffer.

Plasmid construction

The fragments encompassing exon and flanking intronic regions from nine exons were amplified by PCR. The primer designs are shown in Supplementary Table S2. We constructed minigenes with wild-type fragment of each exon into H492-dys plasmid (Nishida et al. 2011; Zhu et al. 2019). Mutations were introduced by Quick Change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA).

Transfection and isolation of RNA

Transfection of the plasmids into HeLa cells was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). At 24 h after transfection, RNAs were prepared by RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Transfection was performed three times for each mutation and wild type.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Real-time RT-PCR amplification was performed as described previously (Nishida et al. 2011). It was performed one time for all RNA products from transfected HeLa cells. PCR products were separated by acrylamide gel electrophoresis and the intensity of each fragment was measured by 1D gel analysis of imageQuant TL (GE Healthcare, USA). Skipping rate was calculated as the intensity of the skipped fragment relative to sum of the skipped and unskipped fragments for each product (We have three products for each mutation). Then it was averaged, and the ratio of wild type was subtracted from each result of mutation for normalization.

Splice site motifs, exon definition metrics

In silico analysis was performed by SpliceAid2 (https://193.206.120.249/splicing_tissue.html) (PIva et al. 2011) and Human Splicing Finder (HSF) (https://www.umd.be/HSF/) tool (Desmet et al. 2009; Kevin et al. 2011).

Results

Clinical characteristics

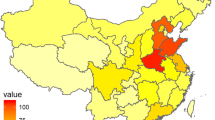

Among 1497 dystrophinopathy patients in our cohort, we found 18 cases with positive dystrophin staining from 363 cases with a nonsense or frameshift mutation in DMD gene. These 18 cases had 18 distinct mutations: 15 nonsense, a small indel, a 2-bp deletion and a 1-bp duplication which were located in exons 9, 25, 27, 31, 37, 38, 41, 72 and 74 (Fig. 1). For comparison, we also included 16 DMD patients with nonsense or frameshift mutations in these exons whose dystrophin was confirmed to be absent on muscle biopsy. Table 1 summarizes the clinical information of the 34 (17 BMD, 4 IMD, and 13 DMD) cases included in this study. Of note, the definitive phenotype of case no. 29, whose dystrophin was expressed on immunohistochemistry, could not be judged, as he is currently 11 years old and still ambulant albeit clinician’s impression was DMD. In cases no. 18, 27, 30 and 34, although their phenotypes were BMD or IMD, dystrophin staining was reported to be negative in the Remudy database. However, the muscle samples were not available, so we could not confirm their dystrophin staining.

Nonsense/frameshift mutations in DMD gene identified in Japanese cohort. A schema representing exons of DMD gene and their reading frame by shape. White circles show position of nonsense/frameshift mutations identified in the patients showing positive dystrophin staining in their muscles. Black circles show positions in the patients with negative dystrophin staining

Transcripts in biopsied muscle

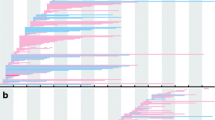

Among 34 cases included in this study, frozen muscle samples were available in ten cases (Table 2). Two PCR products were found in six cases and three products in one case (Fig. 2b–e). Sequencing analysis revealed that the smaller products did not contain the mutated exon, suggesting the cause of exon skipping. However, only unskipped products were obtained in three cases (Fig. 2a, f).

Exon skipping in DMD transcript from the patients with nonsense/frameshift mutations. The RT-PCR products obtained from the control and patients’ muscles are separated on agarose gels. The structure of each PCR product is shown schematically at the right of the panel. The RT-PCR products from the control and some patients showed only a single product (normal sequence) (a, f), while those from the other patients displayed additional shorter products (b–e)

Skipping rate

Two RT-PCR products were amplified from some cells transfected with mutant plasmids, while only a single product was amplified from cells with the wild-type plasmid (Fig. 3b–j). Sequencing analysis revealed that the longer PCR products contained the inserted exon and smaller PCR products contain them exactly without any cryptic splicing. Calculated skipping rate is shown in Table 3. We found higher skipping rates from 0.05 to 0.98 in the nonsense/frameshift mutations were associated with BMD phenotypes, while those were from 0 to 0.03 in the mutations were associated with DMD phenotypes (Table 3). Among 34 cases we examined, 14 mutations caused exon skipping at a skipping rate of more than 0.05, while 18 mutations did not cause it at less than 0.05. Exon skipping rates were well correlated with dystrophin presence/absence and clinical phenotypes, suggesting exon skipping at 5% must be critical for the presence of dystrophin in sarcolemma and milder phenotypes. No exon skipping was observed in three mutations among the BMD cases (no. 17, 26, and 33). In five cases, there was a discrepancy between clinical phenotypes and dystrophin staining in muscles (no. 18, 27, 29, 30, 34), suggesting that dystrophin expression cannot explain the clinical phenotypes or the information of dystrophin expression by physicians might be misjudged. Without these five cases, exon skipping occurrence/non-occurrence was precisely observed in 89% of mutations (24/27).

Nonsense/frameshift mutations caused exon skipping by H492-dys plasmid. a Schematic representation of H492 minigene constructs consisting of DMD gene region encompassing exon harboring a mutation (Dys-Exon) with flanking introns (200 bp each) and two artificial hybrid exons (exon A and B). b–j The RT-PCR products from HeLa cells transfected with wild-type or mutant H492 minigene were separated on agarose gel. The structures of each PCR product are shown at the right of the panels. The longer PCR products were included inserted exon and smaller one did not contain them without any cryptic splicing. *Primer dimer

Splice site motifs, exon definition metrics

By in silico prediction, both destruction of ESE and creations of ESS were predicted in 8 of the 14 mutations. In the remaining six mutations, only ESE destruction was predicted in two mutations, while only ESS creation was predicted in three mutations (Table 4 and Fig. S1).

Discussion

In this study, we found 14 BMD cases with a nonsense/frameshift mutation-mediated exon skipping, which accounts for 38.6% of 363 cases with a nonsense/frameshift mutation in DMD gene and 0.9% of 1497 dystrophinopathy cases in Japan. Albeit rare, it should be noted that there is a risk of misdiagnosis in those cases with such a genotype–phenotype discrepancy if the diagnosis was made solely based on the annotation of the mutations. Naturally, to make a precise diagnosis in such cases, not only genetic testing but also the combination of immunostaining, western blot, cDNA, in silico skipping prediction, and/or minigene analyses should be necessary.

This is the first systematic study to evaluate all DMD mutations which may cause exon skipping by in vitro experiments in the population. This report provides a large list of nonsense/frameshift mutations in DMD gene with exon skip causing rate and patients’ phenotypes. This catalogue could be useful as a reference for curative effects and will also help in further elucidating the nature of the disease.

Previous reports have identified 11 nonsense mutations associated with exon skipping, in exon 25 (Fajkusova et al. 2001; Santos et al. 2014; Zhu et al. 2019), in exon 27 (Shiga et al. 1997), in exon 29 (Ginjaar et al. 2000), in exon 31 (Disset et al. 2006; Nishida et al. 2011; Kevin et al. 2011), in exon 37 (Hamed et al. 2005), in exon 38 (Janssen et al. 2005; Kevin et al. 2011), and in exon 72 (Melis et al. 1998). In this study, we identified 11 nonsense and three frameshift mutations causing exon skipping in exon 9, 25, 27, 31, 37, 38, 41, 72 and 74, indicating the exon skip event is not restricted to nonsense mutations, but also due to other mutations. Nevertheless, all skipped exons were in-frame exons and single exon skipping was detected in all mutations.

As in the previous studies in which single exon skipping was evaluated by RT-PCR from muscle samples, we found single exon skipping in DMD transcripts from patients’ muscles except for the case of exon 27 (Fig. 2). In this study, we further characterized exon skipping events using H492-dys minigene plasmid that encompassed a single exon and flanking intronic regions. There are four advantages in experiments using the artificial minigenes. First, this method enables exon skipping measurement without patient samples. Second, it enables measurement of mutation effect based solely on exon skipping by removing confounding factors, i.e., intronic sequences and trans factors. Third, this method gives an accurate skipping rate without nonsense-mediated degradation of the unskipped transcript as compared to those found in skeletal muscle samples. The skipping rates based on RT-PCR products from skeletal muscles might be overestimated, since unskipped products with nonsense/frameshift undergo degradation by nonsense-mediated RNA decay. Fourth, the minigene assay can be conducted in non-muscle cell line such as Hela cells (Nishida et al. 2011; Zhu et al. 2019), because this nonsense-mediated exon skipping was not related to skeletal muscle-specific alternative splicing, but it will probably be observed in other organs. By this method, in fact, exon skipping occurrence/non-occurrence was reproducibly observed in 89% of mutations. Furthermore, an accurate skipping rate might be useful for predicting patient phenotypes and the results of clinical trials on exon skipping and readthrough.

All the previous reports on BMD with a nonsense mutation presented only the picture of the electrophoresed RT-PCR products as evidence of exon skipping, except for one report presenting sequencing data (Santos et al. 2014) and one in which quantitative data of each DMD transcript in the BMD patient were shown (Zhu et al. 2019). Therefore, the critical rate of exon skipping required for producing BMD phenotypes is still uncertain. In this study, we measured exon skipping rates in 32 mutations and found that when the exon was skipped at more than 5%, patients showed BMD phenotype. Of note, among the four mutations in exon 25, there was a negative correlation between skipping rate and phenotypic severity. In fact, with the mutation no. 9, the skipping rate was 0.73, and the patient could walk until age 54 years, while with the mutation no. 8, the skipping rate was 0.03 and the patient could not walk at age 9 years (Tables 1 and 3).

Our results, however, showed a discordance between the minigene assay and dystrophin immunostaining for mutations. Three mutations (no. 17, 26 and 33) did not induce exon skipping in minigene despite positive dystrophin staining in patients’ muscles and BMD phenotype. Exon 71–78 in DMD gene is known to be the region showing multiple exon splicing patterns in Dp71 (Austin et al. 1995). Nonsense mutations, no. 26 and 33, were located in exon 72 and 74, respectively. If such exons were alternatively spliced, it might be difficult to measure exon skipping rate in HeLa cells by this method. For the remaining mutation (no. 17) and those two mutations (no.26 and 33), we were unable to explain the discrepancy and we could not measure transcripts in muscle, as the muscle biopsy sample was not available.

In previous reports, the critical disruption of ESE or creation of ESS has been suggested to cause exon skipping (Shiga et al. 1997; Disset et al. 2006). By In silico prediction, among the 14 mutations which caused exon skipping, 10 mutations were predicted to disrupt ESE and 12 mutations were predicted to create ESS. From these results, it is strongly suggestive that both ESE disruption and ESS creation should be the mechanism for causing exon skipping. Thus, the in silico prediction is useful for interpreting results of minigene analysis.

Diagnosis is now based mainly on genetic testing and in many cases muscle biopsies are no longer carried out in patients with suspected dystrophinopathy. However, our study demonstrated the importance of biopsy to make a precise diagnosis. The multiple information on genetic tests, clinical information and pathological examination allowed both clinician and researcher to make an inclusive consideration for a prognosis.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Japanese Registry of Muscular Dystrophy (Remudy: https://www.remudy.jp/).

Abbreviations

- BMD:

-

Becker muscular dystrophy

- DMD:

-

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- ESE:

-

Exonic splicing enhancer

- ESS:

-

Exonic splicing silencer

- HSF:

-

Human Splicing Finder

- IMD:

-

Intermediate muscular dystrophy

- Remudy:

-

Registry of muscular dystrophy

References

Anthony K, Arechavala-Gomeza V, Ricotti V, Torelli S, Feng L, Janghra N, Tasca G, Guglieri M, Bbarresi R, Armaroli A, Ferlini A, Bushby K, Straub V, Ricci En Sewry C, Morgan J, Muntoni F (2014) Biochemical characterization of patients with in-frame or out-of-frame DMD deletions pertinent to exon 44 or 45 skipping. JAMA Neurol 71(1):32–40

Austin RC, Howard PC, Souza NDV, Klamut JH, Ray NP (1995) Cloning and characterization of alternatively spliced isoforms of Dp71. Human Mol Genet 4:1475–1483

Beggs AH, Hoffman EP, Snyder JR et al (1991) Exploring the molecular basis for variability among patients with Becker muscular dystrophy: dystrophin gene and protein studies. Am J Hum Genet 49(1):54–67

Deburgrave N, Daoud F, Llense S et al (2007) Protein and mRNA-based phenotype-genotype correlations in DMD/BMD with point mutations and molecular basis for BMD with nonsense and frameshift mutations in the DMD gene. Hum Mutat 28(2):183–195

Desmet FO, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod-Béroud G, Claustres M, Béroud C (2009) Human splicing finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res 37:e67

Disset A, Bourgeois CF, Benmalek N, Claustres MN, Stevenin J, Tuffery-Giraud S (2006) An exon skipping-associated nonsense mutation in the dystrophin gene uncovers a complex interplay between multiple antagonistic splicing elements. Hum Mol Genet 15:999–1013

Fajkusova L, Lukas Z, Tvrdikova M, Kuhrova V, Hajek J, Fajkus J (2001) Novel dystrophin mutation revealed by analysis of dystrophin mRNA; alternative splicing suppresses the phenotypic effect of a nonsense mutation. Neuromuscl Disord 11:133–138

Gatta V, Scarciolla O, Gaspari AR, Palka C, De Angelis MV, Di Mizuno A, Franchi PG, Calabrese G, Uncini A, Stuppia L (2005) Identification of deletions and duplications of the DMD gene in affected males and carrier females by multiples ligation probe amplification (MLPA). Hum Genet 117:92–98

Ginjaar IB, Kneppers AL, vdMeulen JD, Anderson LV, Bremmmer-Bour M, van Deuetekom JC, Weegenaar J, den Dunnen JT, Bakker E (2000) Dystrophin nonsense mutation induces different levels of exon 29 skipping and leads to variable phenotype within one BMD family. Eur J Hum Genet 8:793–796

Hamed S, Sutherlands-Smith A, Gorospe J, Kendrick-Jones J, Hoffman E (2005) DNA sequence analysis for structure/function and mutation studies in Becker muscular dystrophy. Clin Genet 68:69–79

Janssen B, Hartman C, Scholz V, Jauch A, Zschocke J (2005) MLPA analysis for the detection of deletions, duplications and complex rearrangements in the dystrophin gene: potential and pitfalls. Neurogenetics 6:29–35

Kesari A, Pirra LN, Bremadesam L et al (2008) Integrated DNA, cDNA, and protein studies in Becker muscular dystrophy show high exception to the reading frame rule. Hum Mutat 29(5):728–737

Kevin MF, Diane MD, Andrew VN, Payam S, Michael TH, Jacinda BS, Kathryn JS, Mark BB, Jerry RM, Laura ET, Christine BA, Alan P, Julaine MF, Anne MC, Katherine DM, Brenad W, Richard SF, Carsten GB, John WD, Craig M, Robers BW (2011) Nonsense mutation associated Becker muscular dystrophy: Interplay Between exon definition and splicing regulatory elements within the DMD gene. Human Mut 32:299–308

Lalic T, Vossen R, Coffa J, Schouten J, Guc-Scekic M, Radivojevic D, Djurisic M, Breuning MH, Whiete SJ, Dunnen JT (2005) Deletion and duplication screening in the DMD gene using MLPA. Eur J Hum Genet 13:1231–1234

Melis MA, Muntoni F, Cau M, Loi D, Puddu A, Boccone L, Mateddu A, Cianchetti C, Cao A (1998) Novel nonsense mutation (C→A nt 10512) in exon 72 of dystrophin gene leading to ezon skipping in a patient with a mild dystrophinopathy. Hum Mutat 1:S137–S138

Monaco AP, Bertelson CJ, Liechti-Gallati S, Moster H, Kunkel LM (1988) An explanation for the phenotypic differences between patients bearing partial deletions of the DMD locus. Genomics 2:90–95

Nakamura H, Kimura E, Mori YM, Komaki H, Matsuda Y, Goto K, Hayashi YK, Nishino I, Takeda S, Kawai K (2013) Characteristics of Japanese Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy patients in a novel Japanese national registry of muscular dystrophy (Remudy). Orphanet J Rare Dis 8:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-8-60

Nishida A, Kataoka N, Takeshima Y, Yagi M, Awano H, Ota M, Itoh K, Hagiwara M, Matsuo M (2011) Chemical treatment enhances skipping of a mutated exon in the dystrophin gene. Nat Commun 2:301. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1306

Okubo M, Minami N, Goto K, Goto Y, Noguchi S, Mitshuhashi S, Nishino I (2016) Genetic diagnosis of Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy using next-generation sequencing: validation analysis of DMD mutations. J Hum Genet 61:483–489

Okubo M, Goto K, Komaki H, Nakamura H, Mori-Yoshimura M, Hayashi YK, Mitsuhashi S, Noguchi S, Kimura E, Nishino I (2017) Comprehensive analysis for genetic diagnosis of dystrophinopathies in Japan. Orphanet J Rare Dis 12:149. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-017-0703-4

PIva F, Giulietti M, Burini AB, Principato G (2011) SpliceAid2; a database of human splicing factors expression data and RNA target motifs. Human Mut 33:81–85

Santos R, Goncalves A, Oliveira K, Viera E, Vieria JP, Evangelista T, Moreno T, Sanos M, Fineza I, Bronze-da-Rocha E (2014) New variants, challenges and pitfalls in DMD genotyping:o, plications in diagnosis, prognosis and therapy. J Hum Genet 59:454–464

Sherratt TG, Vulliamy T, Dubowitz V, Sewry CA, Strong PN (1993) Exon skipping and translation in patients with frameshift deletions in the dystrophin gene. Am J Hum Genet 53(5):1007–1015

Shiga N, Takeshima Y, Sakamoto H, Inoue K, Yokota Y, Yokoyama M, Matsuo M (1997) Disruption of the splicing enhancer sequence within exon 27 of the dystrophin gene by a nonsense mutation induces partial skipping of the exon and is responsible for Becker muscular dystrophy. J Clin Invest 100:2204–2210

Todorova A, Todorov T, Georgieva B, Lukova M, Guergueltcheva V, Kremensky I, Mitev V (2008) MLPA analysis/complete sequencing of DMD gene in a group of Bulgarian Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy patients. Neuromuscul Disord 18:667–670

Tuffery-Giraud S, Saquet C, Thorel D, Disset A, River F, Malcolm S, Claustres M (2005) Mutation spectrum leading to an attenuated phenotype in dystrophinopathies. Eur J Hum Genet 13:1254–1260

Tuffery-Giraud S, Beroud C, Leturcq F, Yaou RB, Hamroun D, Michel-Calemard L, Moizard MP, Bernard R, Cossée M, Boisseau P, Blayau M, Creveaux I, Guiochon-Mantel A, de Martinville B, Philippe C, Monnier N, Bieth E, Khau Van Kien P, Desmet FO, Humbertclaude V, Kaplan JC, Chelly J, Claustres M (2009) Genotype-phenotype analysis in 2,405 patients with a dystrophinopathy using the UMD-DMD database: a model of nationwide knowledgebase. Hum Mutat 30:934–945. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.20976

Tuffery-Giraud S, Miro J, Koenig M, Clausters M (2017) Normal and altered pre-mRNA processing in the DMD gene. Hum Genet 136:1155–1172

Winnard AV, Klein CJ, Coovert DD et al (1993) Characterization of translational frame exception patients in Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet 2(6):737–744

Zhu Y, Deng H, Chen X, Li H, Yang C, Li S, Pan X, Tian S, Feng S, Tan X, Matsuo M, Zhang Z (2019) Skipping of an exon with a nonsense mutation in the DMD gene is induced by the conversion of a splicing enhancer to a splicing silencer. Hum Genet. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-019-02036-2

Acknowledgements

We express our heartfelt gratitude to patients, families, physicians, and the Japanese Muscular Dystrophy Association for supporting the national dystrophinopathy registry.

Funding

This study was supported partly by Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Research Fellow Grant Number 19J12028, the Intramural Research Grant (28-6, 29-3, 29-4, 30-9) for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of NCNP, and AMED under Grant Numbers JP19ek0109285h0003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MO and SN designed this study, acquired and interpreted the data, and wrote manuscript. SH and MM acquired and interpreted the data. HN and HK analyzed the clinical data. IN participated in planning this study, analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed consent

All clinical information and materials used in the present study were obtained for diagnostic purposes with written informed consent.

Ethic approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okubo, M., Noguchi, S., Hayashi, S. et al. Exon skipping induced by nonsense/frameshift mutations in DMD gene results in Becker muscular dystrophy. Hum Genet 139, 247–255 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-019-02107-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-019-02107-4