Abstract

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are degenerative, multifactorial diseases involving age-related accumulation of extracellular deposits linked to dysregulation of protein homeostasis. Here, we strengthen the evidence that an nsSNP (p.Ala25Thr) in the cysteine proteinase inhibitor cystatin C gene CST3, previously confirmed by meta-analysis to be associated with AD, is associated with exudative AMD. To our knowledge, this is the first report highlighting a genetic variant that increases the risk of developing both AD and AMD. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the risk associated with the mutant allele follows a recessive model for both diseases. We perform an AMD-CST3 case–control study genotyping 350 exudative AMD Caucasian individuals. Bringing together our data with the previously reported AMD-CST3 association study, the evidence of a recessive effect on AMD risk is strengthened (OR = 1.89, P = 0.005). This effect closely resembles the AD-CST3 recessive effect (OR = 1.73, P = 0.005) previously established by meta-analysis. This resemblance is substantiated by the high correlation between CST3 genotype and effect size across the two diseases (R 2 = 0.978). A recessive effect is in line with the known function of cystatin C, a potent enzyme inhibitor. Its potency means that, in heterozygous individuals, a single functional allele is sufficient to maintain its inhibitory function; only homozygous individuals will lack this form of proteolytic regulation. Our findings support the hypothesis that recessively acting variants account for some of the missing heritability of multifactorial diseases. Replacement therapy represents a translational opportunity for individuals homozygous for the mutant allele.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

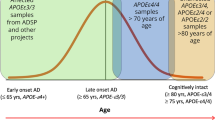

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are progressive neurodegenerative diseases exhibiting some common characteristics. A physical characteristic of both diseases is the presence of insoluble deposits at the site of pathogenesis. These pathological deposits—the amyloid plaques of AD and the drusen of AMD—demonstrate some compositional similarity, engender a pro-inflammatory response and impair essential cellular functions such as trafficking and secretion. These similarities indicate that common/similar cellular mechanisms may contribute towards the pathogenesis of both diseases. Certain environmental risk factors, such as smoking and obesity, are known to increase the risk of both diseases, along with age which is the major risk factor for both conditions. With respect to genetic risk factors the APOE gene is associated with both diseases but quite intriguingly has opposing directions of effect. Whereas the APOE ε4 allele increases risk of developing AD, it decreases the risk of AMD (Baird et al. 2006; Logue et al. 2014; McKay et al. 2011).

A polymorphism in the cystatin C gene (CST3) has also been implicated as a risk factor for both AD (Hua et al. 2012) and AMD (Zurdel et al. 2002). The CST3 polymorphism associated with both diseases is a non-synonymous SNP (rs1064039) in the signal sequence (p.Ala25Thr due to a c.G73A substitution) which results in an alternate homologue referred to as variant B. Cystatin C is a potent inhibitor of cysteine proteases and multiple lines of evidence (from molecular studies) support the hypothesis that wild-type cystatin C has a protective role against both these age-related diseases (Kaeser et al. 2007; Mi et al. 2007).

Meta-analysis of 8 association studies has confirmed that this SNP is associated with AD in Caucasians (Hua et al. 2012). Individuals homozygous for the variant were found to be at greatest risk (ORAA = 1.73, P = 0.005), while heterozygous individuals were not at significantly increased risk (ORAG = 1.06, P = 0.50), indicating that the risk allele acts recessively (Fig. S1). The genetic association between CST3 and AMD has been less well studied, with only a single case–control study reported to date, in which an association between exudative AMD and the polymorphism was highlighted (Zurdel et al. 2002). Mirroring the AD association, Zurdel’s study found that it was those individuals homozygous with the variant that were found to be at the greatest risk of exudative AMD (ORAA = 3.03, P = 0.01), whereas heterozygotes were not at significant risk (ORAG = 1.06, P = 0.76). This identical recessive effect of CST3 on AMD and AD risk is intriguing. In the line of the above, the main aim of this study was to further investigate the AMD-CST3 association.

Methods

Association study subjects and ethics

A total of 350 Caucasian exudative AMD patients (126 males and 224 females) were recruited (age range 65–96 with mean 80.1 years). Written informed consent for all participants used in this study was obtained for research use and approved by the Leeds (East) Research Ethics Committee. The diagnosis of exudative AMD was provided by ophthalmologists based on baseline stereoscopic colour fundus, fluorescein and indocyanine green angiogram images to identify lesion characteristics (McKibbin et al. 2012). Inclusion criteria for the study were that the patients were aged 65 years and over, with choroidal neovascularization (CNV) secondary to AMD and involving the centre of the fovea, and with the CNV occupying more than 50 % of total lesion area. Patients that had CNV secondary to pathological myopia, inflammatory disease, angioid streaks or trauma were excluded from this study. Tests for dementia were not performed on these cases.

Population controls were taken from the largest publicly available online database Exome Variant Server, NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) (January 2014). This provided genotype information for 3781 Caucasians from the USA, which are assumed to contain undiagnosed AMD cases with a frequency equivalent to the Caucasian prevalence. We inferred that 2442 (64.5 %) of this sample are male, in that they have genotype information for the SRY gene.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leucocytes by standard methods. Primers were designed using the online software Primer3 v.0.4.0 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) generated a 1292-bp product using forward primer CST3LRIIF 5′-CAGGAGTGGAGGAGGGAGATG-3′ and reverse primer CST3LRIIR 5′-CCAGATGAGGGGCTCTGTTTT-3′. This product contains three SNPs (rs5030707, rs73318135 and rs1064039) in strong linkage disequilibrium, such that the genetic variation can be explained by two haplotypes, known as variant A and variant B. Two of the SNPs are located in the 5′ untranslated region and the third is located in exon 1 (leading to the missense p.A25T). Briefly, the PCR consisted of 40 ng of genomic DNA, 2pM of each forward and reverse primer, 1M Betaine and HotShot Mastermix (Clent Life Sciences, Stourbridge, UK). An initial denaturation step of 95 °C for 12 min was followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 60 s. A final extension of 75 °C for 5 min completed the reaction. PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1.5 % agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide after which the gel was visualized using the ultraviolet light filter on the ChemiDoc Imaging system (BioRad).

Sanger sequencing

PCR products were digested with ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix USB, Santa Carla, USA) and sequencing reactions were carried out using Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing V3.1 Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). To determine the sequence at SNPs rs5030707, rs73318135 and rs1064039 nested reverse CST3LRR primer 5′-GGCTCCTGGAAGCTGATCTTAG-3′ was used. To confirm the sequence a second nested reverse primer CST3BIIR 5′-TTGCTGGCTTTGTTGTACTCGC-3′ was used. The sequence data obtained from both primers was compared to see if they matched and together these data were used to determine the haplotypes. The sequencing reactions were run on an ABI3130xl Genetic Analyser and the data analysed for respective SNPs using Sequence Analysis 5.2 software (Applied Biosystems). Representative chromatograms of each of the three genotypes are presented in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Statistical analyses

The odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals are log transformed to determine the mean and variance corresponding to the asymptotically normally distributed effect sizes (denoted as β). By calculating these parameters for both the heterozygote (β AG) and homozygote (β AA), we are able to make inferences about the genetic model of inheritance. Explicitly we test for the recessive model by testing the null hypothesis H 0: d = β AA − β AG = 0, H a: d > 0 as previously described (Bagos 2008).

To summarize the level of homogeneity between AMD and AD effect sizes across both genotypes, we calculate the coefficient of determination from the four estimated ORs. We also test the null hypothesis that CST3 has no effect on both diseases, or equivalently that the mean effect size is zero (\(H_{0} :\beta_{\text{AMD}} = \beta_{\text{AD}} = \overline{\beta } = \, 0\)). Here, the weighted mean and variance of the mean (using inverse-variance weighting) are used to determine the appropriate z-score and corresponding P value.

To test whether there is a significant difference in the distribution of three genotypes between AMD cases and controls we performed a two-sided Fisher’s exact test, conducted in R (R Core Team 2014). Meta-analysis was performed using Cochrane Review Manager with Mantel–Haenszel estimation (The Cochrane Collaboration 2012). Random effects meta-regression was performed in R using the ‘glmer’ function from the lme4 package.

Power calculations for AMD association studies of CST3 variant

To determine the power of the association study of Zurdel et al. (2002) a single iteration randomly allocates a genotype (“AA”, “AG” or “GG”) to 517 simulated controls and 167 simulated cases, the sample sizes of this study. The probabilities used to allocate are calculated from the alternative hypothesis effect sizes, which is taken to be that reported by the AD meta-analysis (ORAG = 1.06, ORAA = 1.73). From this simulated case–control dataset we perform a two-tailed z test (on the logORAA scale) at α = 0.05. After 10,000 iterations the number that successfully detected an association is used to estimate power. This is repeated for our study by changing the sample sizes of cases and controls accordingly. For the two-study meta-analysis, power calculation requires simulating the two case–control data sets for each iteration and performing the z test based on the weighted normal distribution (equivalent to a fixed-effect meta-analysis).

Results

Recessive effect of CST3 variant previously observed in both AD and AMD

Association between the CST3 SNP (rs1064039) and AD has been established by meta-analysis (Hua et al. 2012). The exact same SNP has also been identified to be associated with AMD (Zurdel et al. 2002). Using the data from both these studies, we calculate the effect sizes separately for heterozygotes “AG” and homozygotes “AA”, against the baseline “GG” (Fig. 1, Fig. S1). We observe that for both diseases, risk is significantly increased only for the homozygotes (AD: ORAA = 1.73, P = 0.005; AMD: ORAA = 3.03, P = 0.01), whereas the heterozygote risk is non-significant for both diseases (AD: ORAG = 1.06, P = 0.50; AMD: ORAG = 1.06, P = 0.76). Thus a recessive model of inheritance best explains the association with CST3 for both diseases. To support this recessive model we confirm that homozygote effect size is significantly greater than the heterozygote effect size in both AD (P = 0.010) and in AMD (P = 0.013). Put together the risk “A” allele is recessive for both diseases; only individuals with two copies of it are at a significantly higher risk of developing AD and AMD.

To quantify the similarity between the ORAA for AD and AMD, we also calculated how probable it would be to simultaneously observe both these ORs by chance given the null hypothesis that CST3 has no effect on both diseases. We find that such a set of observations is very unlikely to happen by chance (P = 5.0 × 10−4). To further quantify the similarity between the CST3 genotype data of the two diseases, we calculate the coefficient of determination of the four variables (Fig. 1) and find R 2 = 0.673.

Power of existing association studies to detect CST3 recessive effect is estimated to be low

To estimate the power of an association study an estimate of the effect size of the alternative hypothesis is required. Because both molecular and epidemiological evidence support homogeneity between AMD and AD with respect to CST3, we use its AD effect size estimated by meta-analysis (ORAA = 1.73) as a reasonable estimate for its AMD effect size. Using this assumption and a z test for recessive effect we calculate the power of Zurdel’s study (167 cases, 517 controls) to be 24.6 %. Thus for every four studies of such size, only one would detect the association.

We also estimated the power of a GWAS to detect an association with a variant with this recessive effect size. Using the sample sizes, test and significance level of an existing AD GWAS (Harold et al. 2009), we estimated the power to be 14.8 %. One reason for this low power is that the standard GWAS uses a test based on an additive model. This test performs poorly when the true causal variant is recessive (Lettre et al. 2007). We calculated that the per-allele (or additive model) odds ratio, ORA, would be 1.15 given a true recessive effect of ORAA = 1.73 (given the allele frequency of rs1064039 and HWE in controls). From further study of this relationship we found that for a given recessive effect size, ORNN, the perceived per-allele ORN is linearly related to the allele frequency of the SNP (Fig. 2). Thus even a variant with a large recessive effect (ORNN = 3) and moderate allele frequency (10 %) can appear to have a weak effect from its per-allele OR (ORN = 1.2).

The per-allele odds ratio (ORN) decreases linearly with decreasing allele frequency (f N) when the true model is recessive; the elevated risk of homozygotes is kept constant (ORNN specified) and heterozygotes are at baseline risk (ORNX = 1). This relationship can be expressed as: ORN = f N(ORNN − 1) + 1. The single point represents CST3 rs1064039 with respect to AD

Novel AMD-CST3 case–control study consistent with recessive effect

On observing these findings we sought to replicate the finding of Zurdel et al. in investigating the association between CST3 and AMD. The CST3 SNP (rs1064039) was genotyped in Caucasian AMD patients from England (n = 350). We tested this AMD data against the Exome Sequencing Project control data as it was the largest publically available set of population controls (n = 3781). In this control sample the frequency of the variant allele “A” is 17.5 % and the proportion with the “AA” genotype is 3.0 %. Thus the data are in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P = 0.76) and also fall within the allele frequency range reported from the Caucasian studies in the AD meta-analysis, which ranged from 17.1 to 22.8 %.

Case–control analysis of these results exhibits a highly similar pattern of genotype risks to those observed by Zurdel (Table 1), but is not significant at an alpha level of 0.05 (two-sided Fisher’s exact test: P = 0.25). Although not significant, it is the “AA” homozygotes that are at greatest risk (ORAA = 1.56, P = 0.11) compared to the heterozygotes (ORAG = 1.07, P = 0.58), with “GG” homozygotes as baseline. Thus our data are consistent with the recessive effect observed previously in both AMD and AD, but are not powerful enough to reach significance by itself. Further indication of an effect was obtained by performing the analysis only on AMD cases aged above 80 years (ORAA = 2.05, P = 0.03, n = 188). However, all further analyses in this study are performed on the total AMD dataset (i.e. ≥65 years, n = 350).

We calculate the power of our study alone to be 53.7 %, meaning that around half of studies this size would fail to detect the association given the effect size reported for AD. The relatively low powers presented so far are likely due to the frequency of the homozygote risk genotype. For instance within our sample of 350 AMD cases, only 16 (4.6 %) are “AA” homozygotes (Table 1). To achieve a power of 80 % (assuming the effect size is equivalent to AD, ORAA = 1.73), we calculate it would require a sample of 735 AMD cases, whilst maintaining the control sample size of 3781.

Combining AMD-CST3 studies strengthens evidence of a recessive effect

We proceeded to perform a preliminary meta-analysis to bring together the results of the two CST3-AMD association studies. First we apply a fixed-effects meta-analysis to the “AA” genotypes versus the baseline “GG” and determine a significant effect (ORAA = 1.89, P = 0.005) (Fig. 3a). We estimate the power of this two-study meta-analysis to be 67.7 %, greater than either of its constituent association studies as expected. Thus, taken together, the two association studies indicate a significant overall recessive effect of CST3 genotype on AMD risk. We also performed the meta-analysis using a random effects analysis and with this more conservative method the significant recessive effect is maintained (ORAA = 2.00, P = 0.032). We also repeated the random effects meta-analysis using a meta-regression approach (Turner et al. 2000), and found the results matched well (ORAA = 2.17, P = 0.026) with the conventional random effects meta-analysis.

Forest plots for the meta-analysis of CST3 rs1064039 with respect to exudative AMD in the Caucasian population using a fixed effects model. Size of the squares represents the weight of the study and horizontal bars represent 95 % CI of the OR. Applied to a “AA” genotype versus “GG” genotype and b “AG” genotype versus “GG” genotype

We calculated how probable it would be to simultaneously observe both ORAA under the null hypothesis of CST3 having no effect on either disease. We found that this updated set of observations was even more unlikely to happen by chance (P = 7.8 × 10−5) than previously calculated. We then applied an AMD meta-analysis to the “AG” heterozygotes versus the baseline “GG” genotype (Fig. 3b), and determined a non-significant effect (ORAT = 1.06, P = 0.55). Finally, we compared the AMD and AD effect sizes estimated from their respective meta-analysis alongside one another and observed a striking similarity (Fig. 4). Using the updated AMD effect sizes we found that the coefficient of determination now becomes very high (R 2 = 0.978), supporting the hypothesis that homogeneity exists between AMD and AD risk with respect to CST3 genotype.

Discussion

We bring together AD and AMD case–control data and observe that not only is CST3 associated with both diseases but there is a striking similarity in the underlying model of inheritance, namely a recessive genetic model. We first noticed this similarity by bringing together an AD-CST3 meta-analysis and the only reported association study between CST3 and AMD. Under the null hypothesis that both diseases are not affected by CST3 genotype the combined observed data are very unlikely to occur by chance (P = 5.0 × 10−4). However, we estimated the power of this AMD association analysis to be fairly low (24.6 %), assuming the AMD effect size is equivalent to AD. On repeating the AMD association study, again the same recessive trend was observed with only the homozygote variants at elevated risk. Taken together a meta-analysis of the two AMD-CST3 studies finds a significant association (P = 0.005) with an increased estimated power of 67.7 %. The recessive trend is strikingly similar between the two diseases (Fig. 4), with only the “AA” homozygotes at a significantly elevated risk of developing both AMD and AD, whereas the heterozygotes are non-significant and effectively equivalent in both diseases. The combined dataset of all AMD and AD studies is now even more unlikely to occur by chance (P = 7.8 × 10−5) given the null hypothesis that CST3 has no effect on both diseases.

Although an estimated power of 67.7 % was achieved through the two-study meta-analysis, more replication association studies are necessary to validate a role of CST3 in AMD pathogenesis. It is also important to note that both of these AMD association studies were performed with Caucasian samples only. With AD the association with CST3 was only found in Caucasian samples, while in Asian samples no significant AD-CST3 association was detected (Hua et al. 2012). Whether this ethnic disparity also translates across to AMD remains to be determined. A further aspect of the AMD-CST3 association that remains to be unravelled is whether there is any epistasis between CST3 and other known AMD genetic risk factors such as CFH, ARMS2 and APOE.

We are aware that GWASs of AMD have failed to report an association at CST3 (Arakawa et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2010; Cipriani et al. 2012; Fritsche et al. 2013; Neale et al. 2010; Yu et al. 2011). However, the fact that it has not reached genome-wide significance does not preclude it as a risk variant. This is demonstrated by the fact that the AD-CST3 association, validated by candidate gene meta-analysis (Hua et al. 2012), has also not been reported in any GWAS for AD (Harold et al. 2009; Hollingworth et al. 2011; Lambert et al. 2009; Naj et al. 2011; Seshadri et al. 2010), nor a GWAS meta-analysis (Lambert et al. 2013). It follows that all the AD GWASs failed to detect the association, not because there is no association, but because the GWAS must be underpowered to detect it.

One explanation for this is that an association can be missed due to a recessive effect. A limitation of most GWASs is that they utilize a one-degree of freedom test optimal for detecting an additive disease model, but which performs poorly if the actual disease model is recessive (Lettre et al. 2007). We find that the size of this variant’s recessive effect (ORAA = 1.73) is concealed when only considering its additive or per-allele effect size (ORA = 1.15). Herein, we propose that this explanation also serves as a hypothesis to account for some of the current “missing heritability” for common diseases. For AMD only 15–65 % of total heritability is explained by the 19 loci detected so far (Fritsche et al. 2013). A number of hypotheses have sought to predict the nature of the undetected genetic variants that account for this considerable missing heritability. One hypothesis proposes that it is due to common variants with weak effect, also known as the infinitesimal model (Gibson 2011) and has a growing body of supporting evidence (Hunt et al. 2013). We propose that a subset of these common variants with weak effect are likely to be common variants with recessive effect (CVRE). We consider this distinction important as it gives further promise for detecting additional associated variants using currently employed sample sizes. Although a common recessive variant may be considered weak using an additive model, its recessive effect (ORNN) can be much stronger (Fig. 2) and therefore could be detected using an appropriately designed test. We predict that it will be very informative to analyse existing GWAS datasets to test specifically for recessive effects. We consider the CVRE hypothesis is consistent with the knowledge that there are many simple genetic diseases known to be recessive, and that recessive variants are now beginning to be found in complex diseases (Yang et al. 2012). Indeed other candidate gene studies of AMD have discovered associated variants with recessive effect (Jun et al. 2011), which were not detected by the AMD GWASs. The CVRE hypothesis is also consistent with the fact that a recessive variant is more likely to rise to a common allele frequency than a dominant or additive variant because it is under less selective pressure (Curtis 2013).

We present evidence that CST3 is a shared genetic risk factor for both AMD and AD. It was anticipated that variants linked to AMD may contribute to other prevalent age-related diseases involving chronic, local inflammatory processes (Hageman 2012). It has also been documented that both AD plaques and AMD drusen involve amyloid-β peptides and the complex enzymatic systems necessary to generate them (Zhao et al. 2014). A well-known gene implicated in both diseases is APOE. Interestingly however this actually exhibits antagonistic pleiotropy, whereas the ε4 allele increases an individual’s AD risk it decreases AMD risk. Due to this and other unshared risk factors, we do not expect the shared association of CST3 to be sufficient to cause comorbidity between AD and AMD. Indeed a recent study did not find a significant shared incidence between the two diseases (Keenan et al. 2014). However, this is not to say this is a research opportunity not worth exploring; understanding more about the functional mechanism of cystatin C and its associated cellular pathways may provide insights into both diseases, and identify further molecular targets for treatment and prevention. Furthermore, the recessive nature may be favourable with respect to therapeutics; a number of autosomal recessive diseases have already been successfully treated using replacement therapy. Replacing the dysfunctional or deficient gene with a functional copy has been achieved by administering the functional protein (Escobar 2013) and more recently by using gene therapy (Gaudet et al. 2013).

Further support for the CST3 nsSNP having a functional role comes from a recent GWAS that detected an association (P = 7.82 × 10−16) between an SNP 1.3 kb downstream of CST3 (rs6048952) and plasma levels of cystatin C (Akerblom et al. 2014). We found the variant that corresponds to decreased plasma cystatin C is on the same haplotype as the AMD/AD risk allele rs1064039-A (pairwise LD: R 2 = 0.92, D′ = 0.99) (Fig. 5). This observation presents a mechanistic link between genotype and disease phenotype and it also lends further support to the idea that cystatin C replacement therapy may be a fruitful therapeutic avenue. We maintain that the rs1064039 polymorphism is the driver of the reduced secretion because transfection of RPE cells with a construct encoding a different amino acid (serine) at that position leads to an intermediate level of secretion, between the wild type (alanine) and variant B (threonine) levels (Ratnayaka et al. 2007). Decreased secretion of cystatin C has also been observed in fibroblasts taken from AD donors homozygous for variant B when compared with fibroblasts from AD donors heterozygous or wild-type homozygous (Benussi et al. 2003).

Pairwise linkage disequilibrium map of CST3 SNPs (maf >0.05) from a Caucasian sample (n = 503, from Phase 3 of the 1000 Genomes Project). Solid black squares represent pairs of SNPs in high LD (R 2 > 0.9) as depicted by Haploview. Missense SNP highlighted in red, the two other SNPs in the PCR product highlighted in blue, and the SNP associated with plasma level of cystatin C highlighted in green (colour figure online)

In conclusion, we present evidence that strengthens the hypothesis that CST3 is implicated in AMD pathogenesis. In particular, only individuals homozygous for the variant allele are at increased risk. Intriguingly the same recessive effect is observed at the same SNP with AD risk. This finding corresponds with previous evidence from both AD and AMD in vitro models. Observing a recessive effect implies that a single wild-type allele is able to compensate for the mutant allele. This may be due to cystatin C being a potent inhibitor of cysteine proteases (inhibitory constant k i for cathepsin B is 0.25 nM) (Barrett et al. 1984). Therefore, gene expression from a single wild-type copy is expected to maintain proteolytic homeostasis, whereas absence of both wild-type copies is likely to lead to proteolytic dysregulation. It is interesting to note that proteolytic dysregulation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of both AMD and AD (Kaarniranta et al. 2011). Specifically inhibition of cathepsin B has been shown to play an important role in improving memory function and reducing levels of β-amyloid in transgenic AD mice (Hook et al. 2008). It is also interesting that another protease inhibitor, TIMP3, has recently been linked with susceptibility to AMD (Ardeljan et al. 2013; Fritsche et al. 2013). Further research will be required to fully elucidate the roles of protease inhibitors with respect to AMD pathogenesis.

References

Akerblom A, Eriksson N, Wallentin L, Siegbahn A, Barratt BJ, Becker RC, Budaj A, Himmelmann A, Husted S, Storey RF, Johansson A, James SK (2014) Polymorphism of the cystatin C gene in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results from the Platelet inhibition and patient outcomes study. Am Heart J 168(96–102):e2. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2014.03.010

Arakawa S, Takahashi A, Ashikawa K, Hosono N, Aoi T, Yasuda M, Oshima Y, Yoshida S, Enaida H, Tsuchihashi T, Mori K, Honda S, Negi A, Arakawa A, Kadonosono K, Kiyohara Y, Kamatani N, Nakamura Y, Ishibashi T, Kubo M (2011) Genome-wide association study identifies two susceptibility loci for exudative age-related macular degeneration in the Japanese population. Nat Genet 43:1001–1004. doi:10.1038/ng.938

Ardeljan D, Meyerle CB, Agron E, Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Chew EY, Zhao J, Maminishkis A, Chan CC, Tuo J (2013) Influence of TIMP3/SYN3 polymorphisms on the phenotypic presentation of age-related macular degeneration. Eur J Hum Genet 21:1152–1157. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2013.14

Bagos PG (2008) A unification of multivariate methods for meta-analysis of genetic association studies. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 7:Article31. doi:10.2202/1544-6115.1408

Baird PN, Richardson AJ, Robman LD, Dimitrov PN, Tikellis G, McCarty CA, Guymer RH (2006) Apolipoprotein (APOE) gene is associated with progression of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Hum Mutat 27:337–342. doi:10.1002/humu.20288

Barrett AJ, Davies ME, Grubb A (1984) The place of human gamma-trace (cystatin C) amongst the cysteine proteinase inhibitors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 120:631–636

Benussi L, Ghidoni R, Steinhoff T, Alberici A, Villa A, Mazzoli F, Nicosia F, Barbiero L, Broglio L, Feudatari E, Signorini S, Finckh U, Nitsch RM, Binetti G (2003) Alzheimer disease-associated cystatin C variant undergoes impaired secretion. Neurobiol Dis 13:15–21

Chen W, Stambolian D, Edwards AO, Branham KE, Othman M, Jakobsdottir J, Tosakulwong N, Pericak-Vance MA, Campochiaro PA, Klein ML, Tan PL, Conley YP, Kanda A, Kopplin L, Li Y, Augustaitis KJ, Karoukis AJ, Scott WK, Agarwal A, Kovach JL, Schwartz SG, Postel EA, Brooks M, Baratz KH, Brown WL, Brucker AJ, Orlin A, Brown G, Ho A, Regillo C, Donoso L, Tian L, Kaderli B, Hadley D, Hagstrom SA, Peachey NS, Klein R, Klein BE, Gotoh N, Yamashiro K, Ferris Iii F, Fagerness JA, Reynolds R, Farrer LA, Kim IK, Miller JW, Corton M, Carracedo A, Sanchez-Salorio M, Pugh EW, Doheny KF, Brion M, Deangelis MM, Weeks DE, Zack DJ, Chew EY, Heckenlively JR, Yoshimura N, Iyengar SK, Francis PJ, Katsanis N, Seddon JM, Haines JL, Gorin MB, Abecasis GR, Swaroop A (2010) Genetic variants near TIMP3 and high-density lipoprotein-associated loci influence susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:7401–7406. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912702107

Cipriani V, Leung HT, Plagnol V, Bunce C, Khan JC, Shahid H, Moore AT, Harding SP, Bishop PN, Hayward C, Campbell S, Armbrecht AM, Dhillon B, Deary IJ, Campbell H, Dunlop M, Dominiczak AF, Mann SS, Jenkins SA, Webster AR, Bird AC, Lathrop M, Zelenika D, Souied EH, Sahel JA, Leveillard T, Cree AJ, Gibson J, Ennis S, Lotery AJ, Wright AF, Clayton DG, Yates JR (2012) Genome-wide association study of age-related macular degeneration identifies associated variants in the TNXB-FKBPL-NOTCH4 region of chromosome 6p21.3. Hum Mol Genet 21:4138–4150. doi:10.1093/hmg/dds225

Curtis D (2013) Approaches to the detection of recessive effects using next generation sequencing data from outbred populations. Adv Appl Bioinform Chem 6:29–35. doi:10.2147/AABC.S44332

Escobar MA (2013) Advances in the treatment of inherited coagulation disorders. Haemophilia 19:648–659. doi:10.1111/hae.12137

Fritsche LG, Chen W, Schu M, Yaspan BL, Yu Y, Thorleifsson G, Zack DJ, Arakawa S, Cipriani V, Ripke S, Igo RP Jr, Buitendijk GH, Sim X, Weeks DE, Guymer RH, Merriam JE, Francis PJ, Hannum G, Agarwal A, Armbrecht AM, Audo I, Aung T, Barile GR, Benchaboune M, Bird AC, Bishop PN, Branham KE, Brooks M, Brucker AJ, Cade WH, Cain MS, Campochiaro PA, Chan CC, Cheng CY, Chew EY, Chin KA, Chowers I, Clayton DG, Cojocaru R, Conley YP, Cornes BK, Daly MJ, Dhillon B, Edwards AO, Evangelou E, Fagerness J, Ferreyra HA, Friedman JS, Geirsdottir A, George RJ, Gieger C, Gupta N, Hagstrom SA, Harding SP, Haritoglou C, Heckenlively JR, Holz FG, Hughes G, Ioannidis JP, Ishibashi T, Joseph P, Jun G, Kamatani Y, Katsanis N, Keilhauer CN, Khan JC, Kim IK, Kiyohara Y, Klein BE, Klein R, Kovach JL, Kozak I, Lee CJ, Lee KE, Lichtner P, Lotery AJ, Meitinger T, Mitchell P, Mohand-Said S, Moore AT, Morgan DJ, Morrison MA, Myers CE, Naj AC, Nakamura Y, Okada Y, Orlin A, Ortube MC, Othman MI, Pappas C, Park KH, Pauer GJ, Peachey NS, Poch O, Priya RR, Reynolds R, Richardson AJ, Ripp R, Rudolph G, Ryu E et al (2013) Seven new loci associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. doi:10.1038/ng.2578

Gaudet D, Methot J, Dery S, Brisson D, Essiembre C, Tremblay G, Tremblay K, de Wal J, Twisk J, van den Bulk N, Sier-Ferreira V, van Deventer S (2013) Efficacy and long-term safety of alipogene tiparvovec (AAV1-LPLS447X) gene therapy for lipoprotein lipase deficiency: an open-label trial. Gene Ther 20:361–369. doi:10.1038/gt.2012.43

Gibson G (2011) Rare and common variants: twenty arguments. Nat Rev Genet 13:135–145. doi:10.1038/nrg3118

Hageman GS (2012) Age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Moran Eye Center, USA

Harold D, Abraham R, Hollingworth P, Sims R, Gerrish A, Hamshere ML, Pahwa JS, Moskvina V, Dowzell K, Williams A, Jones N, Thomas C, Stretton A, Morgan AR, Lovestone S, Powell J, Proitsi P, Lupton MK, Brayne C, Rubinsztein DC, Gill M, Lawlor B, Lynch A, Morgan K, Brown KS, Passmore PA, Craig D, McGuinness B, Todd S, Holmes C, Mann D, Smith AD, Love S, Kehoe PG, Hardy J, Mead S, Fox N, Rossor M, Collinge J, Maier W, Jessen F, Schurmann B, van den Bussche H, Heuser I, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J, Dichgans M, Frolich L, Hampel H, Hull M, Rujescu D, Goate AM, Kauwe JS, Cruchaga C, Nowotny P, Morris JC, Mayo K, Sleegers K, Bettens K, Engelborghs S, De Deyn PP, Van Broeckhoven C, Livingston G, Bass NJ, Gurling H, McQuillin A, Gwilliam R, Deloukas P, Al-Chalabi A, Shaw CE, Tsolaki M, Singleton AB, Guerreiro R, Muhleisen TW, Nothen MM, Moebus S, Jockel KH, Klopp N, Wichmann HE, Carrasquillo MM, Pankratz VS, Younkin SG, Holmans PA, O’Donovan M, Owen MJ, Williams J (2009) Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 41:1088–1093. doi:10.1038/ng.440

Hollingworth P, Harold D, Sims R, Gerrish A, Lambert JC, Carrasquillo MM, Abraham R, Hamshere ML, Pahwa JS, Moskvina V, Dowzell K, Jones N, Stretton A, Thomas C, Richards A, Ivanov D, Widdowson C, Chapman J, Lovestone S, Powell J, Proitsi P, Lupton MK, Brayne C, Rubinsztein DC, Gill M, Lawlor B, Lynch A, Brown KS, Passmore PA, Craig D, McGuinness B, Todd S, Holmes C, Mann D, Smith AD, Beaumont H, Warden D, Wilcock G, Love S, Kehoe PG, Hooper NM, Vardy ER, Hardy J, Mead S, Fox NC, Rossor M, Collinge J, Maier W, Jessen F, Ruther E, Schurmann B, Heun R, Kolsch H, van den Bussche H, Heuser I, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J, Dichgans M, Frolich L, Hampel H, Gallacher J, Hull M, Rujescu D, Giegling I, Goate AM, Kauwe JS, Cruchaga C, Nowotny P, Morris JC, Mayo K, Sleegers K, Bettens K, Engelborghs S, De Deyn PP, Van Broeckhoven C, Livingston G, Bass NJ, Gurling H, McQuillin A, Gwilliam R, Deloukas P, Al-Chalabi A, Shaw CE, Tsolaki M, Singleton AB, Guerreiro R, Muhleisen TW, Nothen MM, Moebus S, Jockel KH, Klopp N, Wichmann HE, Pankratz VS, Sando SB, Aasly JO, Barcikowska M, Wszolek ZK, Dickson DW, Graff-Radford NR, Petersen RC et al (2011) Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 43:429–435. doi:10.1038/ng.803

Hook VY, Kindy M, Hook G (2008) Inhibitors of cathepsin B improve memory and reduce beta-amyloid in transgenic Alzheimer disease mice expressing the wild-type, but not the Swedish mutant, beta-secretase site of the amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem 283:7745–7753. doi:10.1074/jbc.M708362200

Hua Y, Zhao H, Lu X, Kong Y, Jin H (2012) Meta-analysis of the cystatin C(CST3) gene G73A polymorphism and susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Neurosci 122:431–438. doi:10.3109/00207454.2012.672502

Hunt KA, Mistry V, Bockett NA, Ahmad T, Ban M, Barker JN, Barrett JC, Blackburn H, Brand O, Burren O, Capon F, Compston A, Gough SC, Jostins L, Kong Y, Lee JC, Lek M, MacArthur DG, Mansfield JC, Mathew CG, Mein CA, Mirza M, Nutland S, Onengut-Gumuscu S, Papouli E, Parkes M, Rich SS, Sawcer S, Satsangi J, Simmonds MJ, Trembath RC, Walker NM, Wozniak E, Todd JA, Simpson MA, Plagnol V, van Heel DA (2013) Negligible impact of rare autoimmune-locus coding-region variants on missing heritability. Nature 498:232–235. doi:10.1038/nature12170

Jun G, Nicolaou M, Morrison MA, Buros J, Morgan DJ, Radeke MJ, Yonekawa Y, Tsironi EE, Kotoula MG, Zacharaki F, Mollema N, Yuan Y, Miller JW, Haider NB, Hageman GS, Kim IK, Schaumberg DA, Farrer LA, DeAngelis MM (2011) Influence of ROBO1 and RORA on risk of age-related macular degeneration reveals genetically distinct phenotypes in disease pathophysiology. PLoS One 6:e25775. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025775

Kaarniranta K, Salminen A, Haapasalo A, Soininen H, Hiltunen M (2011) Age-related macular degeneration (AMD): Alzheimer’s disease in the eye? J Alzheimers Dis 24:615–631. doi:10.3233/JAD-2011-101908

Kaeser SA, Herzig MC, Coomaraswamy J, Kilger E, Selenica ML, Winkler DT, Staufenbiel M, Levy E, Grubb A, Jucker M (2007) Cystatin C modulates cerebral beta-amyloidosis. Nat Genet 39:1437–1439. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.23

Keenan TD, Goldacre R, Goldacre MJ (2014) Associations between age-related macular degeneration, Alzheimer disease, and dementia: record linkage study of hospital admissions. JAMA Ophthalmol 132:63–68. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.5696

Lambert JC, Heath S, Even G, Campion D, Sleegers K, Hiltunen M, Combarros O, Zelenika D, Bullido MJ, Tavernier B, Letenneur L, Bettens K, Berr C, Pasquier F, Fievet N, Barberger-Gateau P, Engelborghs S, De Deyn P, Mateo I, Franck A, Helisalmi S, Porcellini E, Hanon O, de Pancorbo MM, Lendon C, Dufouil C, Jaillard C, Leveillard T, Alvarez V, Bosco P, Mancuso M, Panza F, Nacmias B, Bossu P, Piccardi P, Annoni G, Seripa D, Galimberti D, Hannequin D, Licastro F, Soininen H, Ritchie K, Blanche H, Dartigues JF, Tzourio C, Gut I, Van Broeckhoven C, Alperovitch A, Lathrop M, Amouyel P (2009) Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 41:1094–1099. doi:10.1038/ng.439

Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, Jun G, Destefano AL, Bis JC, Beecham GW, Grenier-Boley B, Russo G, Thornton-Wells TA, Jones N, Smith AV, Chouraki V, Thomas C, Ikram MA, Zelenika D, Vardarajan BN, Kamatani Y, Lin CF, Gerrish A, Schmidt H, Kunkle B, Dunstan ML, Ruiz A, Bihoreau MT, Choi SH, Reitz C, Pasquier F, Hollingworth P, Ramirez A, Hanon O, Fitzpatrick AL, Buxbaum JD, Campion D, Crane PK, Baldwin C, Becker T, Gudnason V, Cruchaga C, Craig D, Amin N, Berr C, Lopez OL, De Jager PL, Deramecourt V, Johnston JA, Evans D, Lovestone S, Letenneur L, Moron FJ, Rubinsztein DC, Eiriksdottir G, Sleegers K, Goate AM, Fievet N, Huentelman MJ, Gill M, Brown K, Kamboh MI, Keller L, Barberger-Gateau P, McGuinness B, Larson EB, Green R, Myers AJ, Dufouil C, Todd S, Wallon D, Love S, Rogaeva E, Gallacher J, St George-Hyslop P, Clarimon J, Lleo A, Bayer A, Tsuang DW, Yu L, Tsolaki M, Bossu P, Spalletta G, Proitsi P, Collinge J, Sorbi S, Sanchez-Garcia F, Fox NC, Hardy J, Naranjo MC, Bosco P, Clarke R, Brayne C, Galimberti D, Mancuso M, Matthews F, Moebus S, Mecocci P, Del Zompo M, Maier W et al (2013) Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 45:1452–1458. doi:10.1038/ng.2802

Lettre G, Lange C, Hirschhorn JN (2007) Genetic model testing and statistical power in population-based association studies of quantitative traits. Genet Epidemiol 31:358–362. doi:10.1002/gepi.20217

Logue MW, Schu M, Vardarajan BN, Farrell J, Lunetta KL, Jun G, Baldwin CT, Deangelis MM, Farrer LA (2014) Search for age-related macular degeneration risk variants in Alzheimer disease genes and pathways. Neurobiol Aging 35(1510):e7–e18. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.12.007

McKay GJ, Patterson CC, Chakravarthy U, Dasari S, Klaver CC, Vingerling JR, Ho L, de Jong PT, Fletcher AE, Young IS, Seland JH, Rahu M, Soubrane G, Tomazzoli L, Topouzis F, Vioque J, Hingorani AD, Sofat R, Dean M, Sawitzke J, Seddon JM, Peter I, Webster AR, Moore AT, Yates JR, Cipriani V, Fritsche LG, Weber BH, Keilhauer CN, Lotery AJ, Ennis S, Klein ML, Francis PJ, Stambolian D, Orlin A, Gorin MB, Weeks DE, Kuo CL, Swaroop A, Othman M, Kanda A, Chen W, Abecasis GR, Wright AF, Hayward C, Baird PN, Guymer RH, Attia J, Thakkinstian A, Silvestri G (2011) Evidence of association of APOE with age-related macular degeneration: a pooled analysis of 15 studies. Hum Mutat 32:1407–1416. doi:10.1002/humu.21577

McKibbin M, Ali M, Bansal S, Baxter PD, West K, Williams G, Cassidy F, Inglehearn CF (2012) CFH, VEGF and HTRA1 promoter genotype may influence the response to intravitreal ranibizumab therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol 96:208–212. doi:10.1136/bjo.2010.193680

Mi W, Pawlik M, Sastre M, Jung SS, Radvinsky DS, Klein AM, Sommer J, Schmidt SD, Nixon RA, Mathews PM, Levy E (2007) Cystatin C inhibits amyloid-beta deposition in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Nat Genet 39:1440–1442. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.29

Naj AC, Jun G, Beecham GW, Wang LS, Vardarajan BN, Buros J, Gallins PJ, Buxbaum JD, Jarvik GP, Crane PK, Larson EB, Bird TD, Boeve BF, Graff-Radford NR, De Jager PL, Evans D, Schneider JA, Carrasquillo MM, Ertekin-Taner N, Younkin SG, Cruchaga C, Kauwe JS, Nowotny P, Kramer P, Hardy J, Huentelman MJ, Myers AJ, Barmada MM, Demirci FY, Baldwin CT, Green RC, Rogaeva E, St George-Hyslop P, Arnold SE, Barber R, Beach T, Bigio EH, Bowen JD, Boxer A, Burke JR, Cairns NJ, Carlson CS, Carney RM, Carroll SL, Chui HC, Clark DG, Corneveaux J, Cotman CW, Cummings JL, DeCarli C, DeKosky ST, Diaz-Arrastia R, Dick M, Dickson DW, Ellis WG, Faber KM, Fallon KB, Farlow MR, Ferris S, Frosch MP, Galasko DR, Ganguli M, Gearing M, Geschwind DH, Ghetti B, Gilbert JR, Gilman S, Giordani B, Glass JD, Growdon JH, Hamilton RL, Harrell LE, Head E, Honig LS, Hulette CM, Hyman BT, Jicha GA, Jin LW, Johnson N, Karlawish J, Karydas A, Kaye JA, Kim R, Koo EH, Kowall NW, Lah JJ, Levey AI, Lieberman AP, Lopez OL, Mack WJ, Marson DC, Martiniuk F, Mash DC, Masliah E, McCormick WC, McCurry SM, McDavid AN, McKee AC, Mesulam M, Miller BL et al (2011) Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 43:436–441. doi:10.1038/ng.801

Neale BM, Fagerness J, Reynolds R, Sobrin L, Parker M, Raychaudhuri S, Tan PL, Oh EC, Merriam JE, Souied E, Bernstein PS, Li B, Frederick JM, Zhang K, Brantley MA Jr, Lee AY, Zack DJ, Campochiaro B, Campochiaro P, Ripke S, Smith RT, Barile GR, Katsanis N, Allikmets R, Daly MJ, Seddon JM (2010) Genome-wide association study of advanced age-related macular degeneration identifies a role of the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:7395–7400. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912019107

R Core Team (2014) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Ratnayaka A, Paraoan L, Spiller DG, Hiscott P, Nelson G, White MR, Grierson I (2007) A dual Golgi- and mitochondria-localised Ala25Ser precursor cystatin C: an additional tool for characterising intracellular mis-localisation leading to increased AMD susceptibility. Exp Eye Res 84:1135–1139. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2006.01.030

Seshadri S, Fitzpatrick AL, Ikram MA, DeStefano AL, Gudnason V, Boada M, Bis JC, Smith AV, Carassquillo MM, Lambert JC, Harold D, Schrijvers EM, Ramirez-Lorca R, Debette S, Longstreth WT Jr, Janssens AC, Pankratz VS, Dartigues JF, Hollingworth P, Aspelund T, Hernandez I, Beiser A, Kuller LH, Koudstaal PJ, Dickson DW, Tzourio C, Abraham R, Antunez C, Du Y, Rotter JI, Aulchenko YS, Harris TB, Petersen RC, Berr C, Owen MJ, Lopez-Arrieta J, Varadarajan BN, Becker JT, Rivadeneira F, Nalls MA, Graff-Radford NR, Campion D, Auerbach S, Rice K, Hofman A, Jonsson PV, Schmidt H, Lathrop M, Mosley TH, Au R, Psaty BM, Uitterlinden AG, Farrer LA, Lumley T, Ruiz A, Williams J, Amouyel P, Younkin SG, Wolf PA, Launer LJ, Lopez OL, van Duijn CM, Breteler MM (2010) Genome-wide analysis of genetic loci associated with Alzheimer disease. JAMA 303:1832–1840. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.574

The Cochrane Collaboration (2012) Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3 edn. The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen

Turner RM, Omar RZ, Yang M, Goldstein H, Thompson SG (2000) A multilevel model framework for meta-analysis of clinical trials with binary outcomes. Stat Med 19:3417–3432

Yang HC, Chang LC, Liang YJ, Lin CH, Wang PL (2012) A genome-wide homozygosity association study identifies runs of homozygosity associated with rheumatoid arthritis in the human major histocompatibility complex. PLoS One 7:e34840. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034840

Yu Y, Bhangale TR, Fagerness J, Ripke S, Thorleifsson G, Tan PL, Souied EH, Richardson AJ, Merriam JE, Buitendijk GH, Reynolds R, Raychaudhuri S, Chin KA, Sobrin L, Evangelou E, Lee PH, Lee AY, Leveziel N, Zack DJ, Campochiaro B, Campochiaro P, Smith RT, Barile GR, Guymer RH, Hogg R, Chakravarthy U, Robman LD, Gustafsson O, Sigurdsson H, Ortmann W, Behrens TW, Stefansson K, Uitterlinden AG, van Duijn CM, Vingerling JR, Klaver CC, Allikmets R, Brantley MA Jr, Baird PN, Katsanis N, Thorsteinsdottir U, Ioannidis JP, Daly MJ, Graham RR, Seddon JM (2011) Common variants near FRK/COL10A1 and VEGFA are associated with advanced age-related macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 20:3699–3709. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddr270

Zhao Y, Bhattacharjee S, Jones BM, Hill JM, Clement C, Sambamurti K, Dua P, Lukiw WJ (2014) Beta-amyloid precursor protein (betaAPP) processing in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Mol Neurobiol. doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8886-3

Zurdel J, Finckh U, Menzer G, Nitsch RM, Richard G (2002) CST3 genotype associated with exudative age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol 86:214–219

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge The Royal Wolverhamptom Hospitals NHS Trust for supporting this research. Research in Paraoan laboratory is supported by AgeUK. JT was supported by a Wellcome Trust Biomedical Vacation Scholarship. Thanks to Dr. Jose Luis Ivorra (Ophthalmology and Neuroscience, University of Leeds, UK) for assistance with accessing the data from the Exome Variant Server. JB wishes to express gratitude for the guidance and inspiration of Prof. Jenny Barrett and Prof. Tim Bishop (University of Leeds, UK) within the field of statistics and genetic epidemiology.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

J. M. Butler and U. Sharif share first authorship.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Butler, J.M., Sharif, U., Ali, M. et al. A missense variant in CST3 exerts a recessive effect on susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration resembling its association with Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Genet 134, 705–715 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-015-1552-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-015-1552-7