Abstract

Febrile children below 3 months have a higher risk of serious bacterial infections, which often leads to extensive diagnostics and treatment. There is practice variation in management due to differences in guidelines and their usage and adherence. We aimed to assess whether management in febrile children below 3 months attending European Emergency Departments (EDs) was according to the guidelines for fever. This study is part of the MOFICHE study, which is an observational multicenter study including routine data of febrile children (0–18 years) attending twelve EDs in eight European countries. In febrile children below 3 months (excluding bronchiolitis), we analyzed actual management compared to the guidelines for fever. Ten EDs applied the (adapted) NICE guideline, and two EDs applied local guidelines. Management included diagnostic tests, antibiotic treatment, and admission. We included 913 children with a median age of 1.7 months (IQR 1.0–2.3). Management per ED varied as follows: use of diagnostic tests 14–83%, antibiotic treatment 23–54%, admission 34–86%. Adherence to the guideline was 43% (374/868) for blood cultures, 29% (144/491) for lumbar punctures, 55% (270/492) for antibiotic prescriptions, and 67% (573/859) for admission. Full adherence to these four management components occurred in 15% (132/868, range 0–38%), partial adherence occurred in 56% (484/868, range 35–77%).

Conclusion: There is large practice variation in management. The guideline adherence was limited, but highest for admission which implies a cautious approach. Future studies should focus on guideline revision including new biomarkers in order to optimize management in young febrile children.

What is Known: • Febrile children below 3 months have a higher risk of serious bacterial infections, which often leads to extensive diagnostics and treatment. • There is practice variation in management of young febrile children due to differences in guidelines and their usage and adherence. | |

What is New: • Full guideline adherence is limited, whereas partial guideline adherence is moderate in febrile children below 3 months across Europe. • Guideline revision including new biomarkers is needed to improve management in young febrile children. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fever is a very common presenting symptom in children visiting the emergency department (ED), accounting for approximately 20% of all pediatric emergency visits [1,2,3]. It remains challenging to clinically distinguish the majority having viral illnesses from serious bacterial infections (SBIs) such as urinary tract infection, pneumonia, sepsis, or meningitis. On one hand, this often leads to extensive diagnostic testing, antibiotic prescription, high hospitalization rates, and medical costs [4,5,6]. On the other hand, delayed recognition and treatment of SBIs can lead to substantial morbidity and mortality [7].

Children below 3 months of age have a higher risk of SBI, namely 5–15%, compared to older children due to specific pathogens, their immature immune system, and absent or incomplete vaccinations [6, 8,9,10,11]. Therefore, the threshold for diagnostic testing, antibiotic treatment, and hospital admission is lower in these children. Almost all vaccination programs in Europe start at an age of 2 or 3 months with differences in immunization rates within and across European countries [12, 13].

Currently, several guidelines have been developed for management of febrile children below 3 months [14,15,16]. These guidelines are substantially overlapping, but there is practice variation in guideline usage and adherence [17,18,19]. Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) were successful in safely reducing diagnostic tests, antibiotic treatment and hospital admission with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.30 after implementation of a CPG in 400 children below 2 months at an American ED [20]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline of fever in children under 5 years is predominantly used in Europe [14]. Management in children below 3 months is advised based on a combination of general appearance and biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and white blood cell (WBC) count. The aim of this study is to provide insight in management of febrile children below 3 months attending European EDs, and to assess adherence to available fever guidelines, in order to identify areas for improvement.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study is part of the MOFICHE study (Management and Outcome of Fever in children in Europe), which is embedded in the PERFORM project (Personalized Risk assessment in Febrile illness to Optimize Real-life Management across the European Union) [21]. The MOFICHE study is an observational multicenter study evaluating management and outcome of febrile children in twelve EDs across eight European countries (Austria, Germany, Greece, Latvia, the Netherlands n = 3, Slovenia, Spain, UK n = 3). The hospital characteristics are shown in Appendix A and described in a previous study [13]. Approval by the ethics committees of the participating hospitals was obtained. The need for informed consent was waived.

Study population

Data of 38,480 children with fever (≥ 38 ℃) at the ED or in three consecutive days before ED visit aged 0–18 years were collected between January 2017 and April 2018. For this study, only febrile children below 3 months of age were included. Children with comorbidities or missing data on management were excluded. Additionally, we excluded febrile children with bronchiolitis caused by respiratory syncytial virus for the analysis concerning guideline adherence, since management differs in these children [22].

Data collection

Data were routinely collected from electronic patient records in a standardized pseudo-anonymized database for at least 1 year to include all four seasons, wherein inclusion varied from 1 week per month to the whole month per ED (Appendix A). The collected data included patient characteristics (age, gender, comorbidity (chronic condition expected to last at least 1 year [23]), presenting symptoms), disease severity (triage urgency, type of referral, vital signs), diagnostic tests (laboratory tests, imaging), antibiotic treatment, admission, focus, and cause of infection. Presenting symptoms were categorized into four groups: neurological (focal neurological signs or meningeal signs), respiratory (coughing or other signs of respiratory infections), gastrointestinal (vomiting or diarrhea), and other (non-specified)). Age specific cutoff values from Advanced Pediatric Life Support were used to categorize the vital signs into tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypoxia [24]. Increased work of breathing was defined as the occurrence of chest wall retractions, nasal flaring, grunting, or apneas. Focus of infection was categorized into upper respiratory tract, lower respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, flu-like illness or childhood exanthemas, soft tissue, skin or musculoskeletal infection, sepsis or meningitis, and other (e.g., undifferentiated fever, inflammatory illness). Lastly, the cause of infection was determined by the research team using a previously published phenotyping algorithm [5, 25] (Appendix B). It combines clinical data and diagnostic results to assign the presumed cause of infection. The cause of infection was categorized into definite bacterial, probable bacterial, bacterial syndrome, unknown bacterial or viral, definite viral, probable viral, viral syndrome, and other (e.g., inflammatory illness). SBI was defined as a lower respiratory tract infection, gastrointestinal infection, urinary tract infection, sepsis, meningitis, or musculoskeletal infection in combination with a probable or definite bacterial cause.

Outcome measures

The main outcome of this study is management, which is divided into diagnostic tests, antibiotic treatment, and hospital admission. Diagnostic tests are categorized into simple and advanced diagnostic tests, where simple is considered less invasive, and advanced is considered more invasive for the child. Simple diagnostic tests included CRP, WBC count, Procalcitonin (PCT), urinalysis, urine culture, ultrasound, chest X-ray, respiratory test, or sputum culture. Blood culture, lumbar puncture, CT scan, or MRI scan are considered advanced diagnostic tests. If patients underwent both simple and advanced diagnostic tests, they were classified as advanced. Data on antibiotic prescription as well as group of antibiotics (narrow or broad spectrum) and route of administration (oral or parenteral) were collected. Narrow spectrum antibiotics included penicillins and first-generation cephalosporins. Broad spectrum antibiotics included penicillins with beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations, macrolides, aminoglycoside, glycopeptides, and second- and third-generation cephalosporins [5]. Children were discharged home or admitted to the pediatric ward (< 24 h or > 24 h) or pediatric intensive care unit.

The principal investigator of each hospital was asked which guideline for fever was available at their ED. A distinction was made into NICE, national or local guidelines for fever. Additionally, they were asked whether their guideline for fever was based on the NICE guideline for fever and specifically if the guideline contained the same diagnostic and therapeutic strategies as the NICE guideline [14], shown in Table 1. The four most important components of management according to the guidelines were compared with actual management performed in clinical practice at the ED: blood culture, lumbar puncture, antibiotic treatment, and hospital admission. Full adherence was defined as having blood cultures, lumbar punctures, antibiotic treatment, and hospital admission, all according to the recommendations of the available guideline for fever. Partial adherence was defined as following one to three of these four components. Children were classified as non-adherent when none of the four components was performed according to the guideline.

Data analysis

Firstly, descriptive statistics were used to describe clinical characteristics and management. The range per ED was shown as well to show the variability. Additionally, management was shown stratified for EDs with high and low prevalence of SBI. The cutoff value for a high prevalence of SBI was 12%, which was determined by the prevalence of SBI in our study population. Secondly, management performed including blood culture, lumbar puncture, antibiotic treatment, and hospital admission of children below 3 months was compared to the available guideline for fever per ED. Subsequently, we performed subgroup analyses in children below 1 month and children 1–3 months. Thirdly, we analyzed the three adherence groups (full, partial, non) stratified for working diagnosis. Working diagnosis was categorized into presumed bacterial (definite bacterial, probable bacterial, bacterial syndrome), presumed viral (definite viral, probable viral, viral syndrome), and unknown bacterial or viral or other cause (Appendix B). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS software version 25.

Results

Patient characteristics and management

The population for analysis consisted of 913/38,480 (2%) febrile children below the age of 3 months. The median age was 1.7 months (IQR, 1.0–2.3) and the majority were boys (58%). Fifty-four percent of the children were referred by a physician and triaged as intermediate/high urgent (53%). The respiratory tract was the most common focus of infection, and the majority had a viral cause of infection (Table 2) (Appendix C). The causative pathogens stratified for bacteria and viruses are shown in Appendix D. Management in children below 3 months is also shown in Table 2. Only simple diagnostic tests were performed in 37%, of which CRP and WBC were performed most frequently (75% and 73%). Advanced diagnostics tests were performed in 44%, of which blood cultures were performed in 43% and lumbar punctures in 22%. Antibiotics were prescribed in 41% of which the majority received parenteral (92%) and broad spectrum antibiotics (89%). Sixty-eight percent of the children were admitted, of which 80% were admitted more than 24 h. Management per ED varied as shown in Table 2 and management was not associated with the prevalence of SBI at the ED as shown in Appendix E.

Guideline adherence

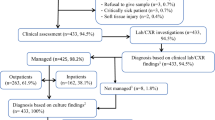

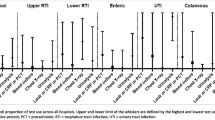

Guideline adherence in febrile children (excluding bronchiolitis) below 3 months (N = 868) is shown in Fig. 1 and the range per ED is shown in Appendix F. Guideline adherence varied as follows: blood cultures were obtained in 43% (374/868, range 13–67%), lumbar punctures in 29% (144/491, range 0–62%), antibiotics were prescribed in 55% (270/492, range 33–80%), and 67% (573/859, range 31–91%) were admitted. Full adherence to the guideline occurred in 15% (132/868, range 0–38%), partial adherence to the guideline occurred in 56% (484/868, range 35–77%), and no adherence occurred in 29% (252/868, range 13–45%). The majority fulfilled the criteria of partial adherence since these children were admitted according to the guideline (441/484, 91%). The three adherence groups stratified for working diagnosis are shown in Fig. 2. Twenty-one percent (186/868) of the children had a presumed bacterial infection, 54% (467/868) had a presumed viral infection, and 25% (215/868) had an unknown or other infection. In children with a presumed bacterial infection, full adherence occurred in 23% (42/186), partial adherence in 71% (133/186), and 90% (167/186) were admitted. In children with a presumed viral infection, full adherence occurred in 14% (66/467), partial adherence occurred in 51% (239/467), and 61% were admitted (283/467). Management and guideline adherence stratified for children below 1 month (N = 231) and 1 to 3 months (N = 682) is shown in Appendix G. Children below 1 month received more often advanced diagnostic tests (50% versus 42%), received antibiotic treatment more frequently (55% versus 36%), and were admitted more frequently (76% versus 65%) compared with children aged 1 to 3 months. Full adherence to the guideline in children below 1 month was 32% (71/223) compared with 10% (61/645) in children aged 1 to 3 months.

Discussion

Main findings

In this study, we examined management and guideline adherence in febrile children below 3 months, which covers 2% of the total pediatric population with fever attending twelve European EDs. Twelve percent of these children had a SBI which corresponds with previous literature where the percentage of SBI in children below 3 months varied between 5 and 15% [6, 8, 9]. There was large practice variation in management across the EDs, in which diagnostic tests ranged from 14 to 83%, antibiotic treatment ranged from 23 to 54%, and admission ranged from 34 to 86%. No association between settings with a high prevalence of SBI (> 12%) and more extensive management was found. Full guideline adherence was limited, namely 15% (132/868, range 0–38%), but partial guideline adherence was moderate 56% (484/868, range 35–77%), of which the majority (91%) were adherent to the admission component. In the subgroup analysis, we have seen that full adherence to the guideline occurred more often in children below 1 month compared with children 1–3 months (32% versus 10%). When we describe the four management components separately, guideline adherence varied as follows: a blood culture was obtained in 43%, a lumbar puncture in 29%, antibiotic treatment was given in 55%, and 67% were admitted. The high percentage of adherence for hospital admission (67%) could be interpreted as a cautious approach. The low adherence for lumbar punctures could be due to the physicians’ decision but also due to failure of lumbar punctures, which was described to occur in 38% of children below 3 months [26]. Additionally, in children with a presumed bacterial infection, full guideline adherence occurred in 23%, partial guideline adherence occurred in 71%, and 90% were admitted. In children with a presumed viral infection, full guideline adherence occurred in 14%, partial guideline adherence in 51%, and 61% was admitted.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine actual management and adherence to guidelines for fever in children below 3 months using a large European multicenter ED cohort. High-quality routine data was collected extensively, which made it possible to compare actual management (diagnostic tests, treatment, admission) with the management recommended by the guidelines for fever. There are some limitations as well. No data on follow-up was collected in this study, which made it difficult to interpret the outcome of guideline adherence. However, the majority were admitted and we used the phenotyping algorithm as proxy for the working diagnosis, which had a good performance in allocating a bacterial cause of infection [25]. Additionally, we had data on whether children died and this was not the case in our cohort. Participating EDs were part of large university or teaching hospitals, which might limit generalizability to general hospitals. However, an additional analysis examining management stratified for prevalence on SBI did not show any differences in management. The hypothesis that EDs would perform more extensive management when the proportion of children with SBI is high was not reflected in the results, which implies that differences in management across EDs do not appear to be related to the prevalence of SBI (Appendix E). Lastly, we defined adherence as management performed according to the guideline and non-adherence as management not performed as recommended by the guideline. However, there was a small proportion of children in whom extensive management was performed in whom it was not recommended by the guideline, but other factors might have led to these diagnostics and treatment. We did not allocate these cases as non-adherent.

Implications for clinical practice

This study shows large practice variation in management across EDs and limited full adherence, but moderate partial adherence to guidelines for fever, which once again highlights that managing these febrile children below 3 months is challenging. On one hand, missing SBIs can lead to morbidity and even mortality. On the other hand, these children often receive extensive diagnostic testing and antibiotic treatment and are admitted leading to high medical costs and great impact on children and parents. The discussion on diagnostic uncertainty and hospitalization of febrile children below 3 months already started about 40 years ago, when a study by DeAngelis et al. showed that approximately 20% of hospitalized, febrile children below 2 months had complications due to diagnostic tests, antibiotic treatment, or the hospitalization itself [27]. Since then, many studies examined the use of guidelines and prediction models for the risk of SBI in young febrile children to reduce antibiotic treatment and hospital admission. The adherence to the guidelines for fever was limited in our study, which may raise the question whether our current guidelines are interpreted differently and probably too cautious. However, when children were not fully managed according to the guideline, most of them were admitted and this implies a cautious approach. Furthermore, management at the ED can be influenced by many factors, such as parental concern, physicians’ working experience, overcrowding, and nurses’ and physicians’ gut feeling. However, overall clinical impression of experienced nurses at the ED is not an accurate predictor of serious illness in children and clinician’s gut feeling is not predictive for diagnosing SBIs [28, 29]. We suggest to improve management of febrile children below 3 months by revising the guidelines, since physicians make different decisions regarding management than is recommended by the guidelines. Before revising the guidelines, it would be beneficial if physicians can substantiate their decision-making concerned management including blood culture, lumbar puncture, and antibiotic prescription in cases of febrile children below 3 months attending the ED. Additionally, as the final cause of infection was predominantly viral, there is room for improvement in management by reducing antibiotics and admission in this group, which contributes to lowering antimicrobial resistance and medical costs associated with admission. The American Academy of Pediatrics’ CPG for febrile children below 2 months recommend less extensive management based on age and well appearance but should be validated in a European cohort [30]. The proportion of full adherence to the guideline was higher for bacterial than for viral infections, which implies that the guidelines are contributing to the decision-making process. However, CPGs should be improved to guide decision-making, since none of several CPG’s studied demonstrated ideal performance characteristics in previous research [31]. Discovery and implementation of a new biomarker in the guidelines for young febrile children could improve the ability to make a better distinction between bacterial or viral infections. A promising biomarker in distinguishing bacterial and viral infections in febrile children is based on the RNA host response [32,33,34].

Conclusion

There is large practice variation in management in febrile children below 3 months attending European EDs. Full guideline adherence was limited, but highest in children with a presumed bacterial infection. Partial adherence was moderate, with highest compliance for admission, which implies a cautious but expensive approach. Future studies should focus on guideline revision including new biomarkers in order to optimize management in young febrile children.

Change history

21 October 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04664-9

Abbreviations

- CPG:

-

Clinical practice guideline

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- MOFICHE:

-

Management and outcome of fever in children in Europe

- NICE:

-

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- PCT:

-

Procalcitonin

- PERFORM:

-

Personalized risk assessment in febrile illness to optimize real-life management across the European Union

- SBI:

-

Serious bacterial infection

- WBC:

-

White blood cell count

References

Massin MM, Montesanti J, Gérard P, Lepage P (2006) Spectrum and frequency of illness presenting to a pediatric emergency department. Acta Clin Belg 61(4):161–165

Sands R, Shanmugavadivel D, Stephenson T, Wood D (2012) Medical problems presenting to paediatric emergency departments: 10 years on. Emerg Med J 29(5):379–382

Poropat F, Heinz P, Barbi E, Ventura A (2017) Comparison of two European paediatric emergency departments: does primary care organisation influence emergency attendance? Ital J Pediatr 43(1):29

Borensztajn DM, Hagedoorn NN, Rivero Calle I, Maconochie IK, von Both U, Carrol ED et al (2021) Variation in hospital admission in febrile children evaluated at the Emergency Department (ED) in Europe: PERFORM, a multicentre prospective observational study. PLoS ONE 16(1):e0244810

Hagedoorn NN, Borensztajn DM, Nijman R, Balode A, von Both U, Carrol ED et al (2020) Variation in antibiotic prescription rates in febrile children presenting to emergency departments across Europe (MOFICHE): a multicentre observational study. PLoS Med 17(8):e1003208

Leigh S, Grant A, Murray N, Faragher B, Desai H, Dolan S et al (2019) The cost of diagnostic uncertainty: a prospective economic analysis of febrile children attending an NHS emergency department. BMC Med 17(1):48

Boeddha NP, Schlapbach LJ, Driessen GJ, Herberg JA, Rivero-Calle I, Cebey-López M et al (2018) Mortality and morbidity in community-acquired sepsis in European pediatric intensive care units: a prospective cohort study from the European Childhood Life-threatening Infectious Disease Study (EUCLIDS). Crit Care 22(1):143

Byington CL, Enriquez FR, Hoff C, Tuohy R, Taggart EW, Hillyard DR et al (2004) Serious bacterial infections in febrile infants 1 to 90 days old with and without viral infections. Pediatrics 113(6):1662–1666

Greenhow TL, Hung YY, Herz AM, Losada E, Pantell RH (2014) The changing epidemiology of serious bacterial infections in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 33(6):595–599

Clapp DW (2006) Developmental regulation of the immune system. Semin Perinatol 30(2):69–72

Fernandez Colomer B, Cernada Badia M, Coto Cotallo D, Lopez Sastre J, Grupo Castrillo N (2020) The Spanish National Network “Grupo Castrillo”: 22 Years of Nationwide Neonatal Infection Surveillance. Am J Perinatol 37(S02):S71–S5

ECDC European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2021) Vaccine scheduler: agency of the European Union. Available from: https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/

Borensztajn D, Yeung S, Hagedoorn NN, Balode A, von Both U, Carrol ED et al (2019) Diversity in the emergency care for febrile children in Europe: a questionnaire study. BMJ Paediatr Open 3(1):e000456

NICE guideline (2019) Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management: NICE National Insitute for Health and Care Excellence. Updated November 7, 2019. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng143

Palladino L, Woll C, Aronson PL (2019) Evaluation and management of the febrile young infant in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract 16(7):1–24

Cioffredi LA, Jhaveri R (2016) Evaluation and management of febrile children: a review. JAMA Pediatr 170(8):794–800

Meehan WP 3rd, Fleegler E, Bachur RG (2010) Adherence to guidelines for managing the well-appearing febrile infant: assessment using a case-based, interactive survey. Pediatr Emerg Care 26(12):875–880

Klarenbeek NN, Keuning M, Hol J, Pajkrt D, Plötz FB (2020) Fever without an apparent source in young infants: a multicenter retrospective evaluation of adherence to the Dutch guidelines. Pediatr Infect Dis J 39(12):1075–1080

van de Maat J, Jonkman H, van de Voort E, Mintegi S, Gervaix A, Bressan S et al (2020) Measuring vital signs in children with fever at the emergency department: an observational study on adherence to the NICE recommendations in Europe. Eur J Pediatr 179(7):1097–1106

Mercurio L, Hill R, Duffy S, Zonfrillo MR (2020) Clinical practice guideline reduces evaluation and treatment for febrile infants 0 to 56 days of age. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 59(9–10):893–901

PERFORM (2021) Personalised risk assessment in febrile illness to optimise real-life management (PERFORM). Available from: https://www.perform2020.org/

NICE guideline (2015) Bronchiolitis in children: diagnosis and management: NICE National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Updated June 1, 2015. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng9

Simon TD, Cawthon ML, Stanford S, Popalisky J, Lyons D, Woodcox P et al (2014) Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: a new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics 133(6):e1647–e1654

Turner NM (2017) Advanced paediatric life support. 5th ed: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum

Nijman RG, Oostenbrink R, Moll HA, Casals-Pascual C, von Both U, Cunnington A et al (2021) A novel framework for phenotyping children with suspected or confirmed infection for future biomarker studies. Front Pediatr 9:688272

Bedetti L, Lugli L, Marrozzini L, Baraldi A, Leone F, Baroni L et al (2021) Safety and success of lumbar puncture in young infants: a prospective observational study. Front Pediatr 9:692652

DeAngelis C, Joffe A, Wilson M, Willis E (1983) Iatrogenic risks and financial costs of hospitalizing febrile infants. Am J Dis Child 137(12):1146–1149

Zachariasse JM, van der Lee D, Seiger N, de Vos-Kerkhof E, Oostenbrink R, Moll HA (2017) The role of nurses’ clinical impression in the first assessment of children at the emergency department. Arch Dis Child 102(11):1052–1056

Urbane UN, Gaidule-Logina D, Gardovska D, Pavare J (2019) Value of parental concern and clinician’s gut feeling in recognition of serious bacterial infections: a prospective observational study. BMC Pediatr 19(1):219

Pantell RH, Roberts KB, Adams WG, Dreyer BP, Kuppermann N, O'Leary ST et al (2021) Evaluation and management of well-appearing febrile infants 8 to 60 days old. Ped 148(2)

Waterfield T, Maney JA, Fairley D, Lyttle MD, McKenna JP, Roland D et al (2021) Validating clinical practice guidelines for the management of children with non-blanching rashes in the UK (PiC): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 21(4):569–577

Herberg JA, Kaforou M, Wright VJ, Shailes H, Eleftherohorinou H, Hoggart CJ et al (2016) Diagnostic Test accuracy of a 2-transcript host RNA signature for discriminating bacterial vs viral infection in febrile children. JAMA 316(8):835–845

Mejias A, Cohen S, Glowinski R, Ramilo O (2021) Host transcriptional signatures as predictive markers of infection in children. Curr Opin Infect Dis

Mahajan P, Kuppermann N, Mejias A, Suarez N, Chaussabel D, Casper TC et al (2016) Association of RNA biosignatures with bacterial infections in febrile infants aged 60 days or younger. JAMA 316(8):846–857

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 848196. The Research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres at Imperial College London, Newcastle Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Newcastle University. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. For the remaining authors, no sources of funding were declared. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design of the study and the interpretation of the findings. CT and EW performed the analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by all the participating hospitals: Austria (Ethikkommission Medizinische Universität Graz, ID: 28–518 ex 15/16), Germany (Ethikkommission der LMU München, ID: 699–16), Greece (Ethics committee, ID: 9683/18.07.2016), Latvia (Centrala medicinas etikas komiteja, ID: 14.07.201 6. No. Il 16–07 -14), Slovenia (Republic of Slovenia National Medical Ethics Committee, ID: ID: 0120–483/2016–3), Spain (Comité Autonómico de Ética de la Investigación de Galicia, ID: 2016/331), The Netherlands (Commissie Mensgebonden onderzoek, ID: NL58103.091.16), UK (Ethics Committee, ID: 16/LO/1684, IRAS application no. 209035, Confidentiality advisory group reference: 16/CAG/0136).

Consent to participate

No informed consent was needed for this study. In all the participating UK settings, an additional opt-out mechanism was in place.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Peter de Winter

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The presentation of Table 2 has been corrected.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, C.D., van der Walle, E.E.P.L., Vermont, C.L. et al. Guideline adherence in febrile children below 3 months visiting European Emergency Departments: an observational multicenter study. Eur J Pediatr 181, 4199–4209 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04606-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04606-5