Abstract

In Italy, where neonatal jaundice treatment is required, it is largely carried out in hospitals. However, it is possible to safely administer home phototherapy (HPT). We report our pilot center’s experience of HPT and its potential benefits during the COVID-19-enforced national lockdown. This is an observational study performed at the Policlinic Abano Terme, a suburban hospital that covers a large catchment area near the Euganean Hills in Northeast Italy with around 1000 deliveries per year. HPT was started after regular nursery discharge, and the mothers brought the neonates back to the hospital maternity ward each day to check infants’ bilirubin levels, weight, and general state of health, until it was deemed safe to stop. The efficacy of HPT in bilirubin reduction, hospital readmission rates, and parental satisfaction were evaluated. Thirty infants received HPT. In 4 of these infants, HPT was associated with total serum bilirubin (TSB) between 75 and 95th percentile (high-intermediate-risk zone) and in 26 infants HPT was associated with TSB > 95th percentile (high-risk zone) of the Bhutani nomogram. Among these 30 infants, 27 (90%) completed the HPT with a progressive decrease of TSB levels with 4 neonates requiring a second course and 3 infants requiring a third course of 24-h HPT. Three (10%) neonates failed HPT and were readmitted after one 24-h phototherapy course. No abnormalities of breastfeeding, body weight (defined as > 10% decrease), temperature, nor COVID infections were detected following HPT consultation in the neonatal ward. Home treatment efficacy with varying degrees of parental satisfaction occurred in all but 3 cases that involved difficulties with the equipment and inconsistent lamp manipulation practices.

Conclusion: Our pilot study suggests that HPT for neonatal jaundice can be carried out effectively and with parental satisfaction as supported by daily back bilirubin monitoring in the maternity ward during the enforced COVID-19 national lockdown in Italy.

What is Known: • No high-quality evidence is currently available to support or refute the practice of phototherapy in patients’ own homes. | |

What is New: • Phototherapy can be delivered at home in a select group of infants and could be an ideal option if parents are able to return with their infants to the hospital maternity ward for daily follow-up. • It can be as effective as inpatient phototherapy and potentially helps in delivering family-centered care. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Phototherapy is the most widely used form of therapy for the treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in the first days of life [1]. It is now possible to safely administer home phototherapy (HPT) for jaundice in patients’ own homes in several high-income countries as an alternative to hospital-based phototherapy [2, 3]. The recent Chu and al. metanalysis [4], including a total of 259 neonates, suggests that home-based phototherapy is even more effective than hospital-based phototherapy in the treatment of neonatal jaundice. Clinical advantages of home-centered phototherapy include reduced cost, avoidance of parent‐infant separation to decrease maternal psychoemotional distress and increase mother-infant bonding, breastfeeding success, and parental satisfaction [5].

However, routine in-hospital and at-home neonatal jaundice treatment/surveillance and follow-up strategies have become challenging in the era of COVID-19 owing to rigorous quarantine protocols and other infectious control measures undertaken to decrease the spread of the virus [6]. In response to COVID-19, hospitals changed their policies and protocols regarding perinatal care, canceling birth center tours as well as barring nonessential visits to the laboring mom, the delivery room, and the postpartum units. This has the effect of increasing stress stemming from isolation, anxiety over disease status, and apprehension in response to new maternal responsibilities, making lockdown in the hospital challenging for maternal mental health [7].

In this context, we hypothesized that the treatment of hyperbilirubinemia at home may provide a useful way to alleviate postpartum maternal psychoemotional distress in times of widespread lockdown such as the enforced Italy-wide COVID-19 lockdown [8].

We developed an HPT pilot program for convenient treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, which was set up in 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic. The program was designed with prevention of COVID-19 infection specifically in mind. We report on our center’s experience of this HPT service and analyze the outcomes for infants treated at home. The primary outcome was to evaluate the effectiveness of HPT as represented by the rate of fall of bilirubin, duration of HPT, and hospital readmission rates, while paying close attention to the prevention and control of COVID-19 infection. The secondary outcome was evaluation of parental satisfaction.

Patients and methods

We conducted a pilot study of home phototherapy (HPT) for neonatal jaundice in the context of restrictive strategies adopted for maternity services in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. The analysis was conducted between June 1 and December 31, 2021, at the Policlinic Abano Terme, Abano Terme, Italy. The hospital where this study took place is located in an industrialized area of Northeast Italy, which borders the municipalities of the COVID-19 Euganean Hills “hotspot.” It supports about 1000 births per year among pregnant women with low and late fertility, high socioeconomic status, high employment rate, and advanced educational levels [7]. This pilot program was staffed by a maternity nursing and consultant team that would monitor bilirubin levels from the infants’ backs for 7 days after the start of HPT. Policlinic Abano Terme Ethics Committee consent was obtained.

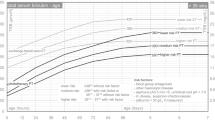

Pregnant women were first given information about the pilot study at the antenatal healthcare center and again pre-discharge when they gave informed consent to HPT via signature. In accordance with clinical routines, two-step delivery, cord clamping “not earlier than one minute” [9], and short hospitalization (discharge on day two after both vaginal and cesarean delivery) were the clinical standard procedures in the hospital before and during the study for uncomplicated pregnancies. During their stay, newborns roomed-in with their mothers, who were encouraged to demand-feed them; they received complementary formula milk if breast milk intake was judged to be insufficient. In our maternity ward, at 48 h of age, capillary heel blood samples for total serum bilirubin (TSB) levels and complementary hematocrit (Hct) levels are obtained by a midwife or neonatal nurse in conjunction with routine metabolic screenings. Healthy late preterm (> 35 weeks) and term infants are typically discharged on day 2 taking into account the hour-specific nomogram developed by Bhutani to predict the subsequent hyperbilirubinemia risk zones [10]: 1. TSB level < 75th percentile (low-risk or low–intermediate-risk zone); 2. TCB level between 75 and 95th percentile (high-intermediate-risk zone); and 3. TCB level > 95th percentile (high-risk zone): the risk of subsequent significant hyperbilirubinemia is very high.

The eligibility criteria for HPT included near-term and term infants, body weight decrease of less than 10%, no Rh or major ABO isoimmunisation as would be indexed by a positive direct antiglobulin test, no IUGR and serious congenital malformations, and no syndromes or other congenital diseases that could affect the outcome measures. In addition, to be eligible for HPT, parents needed to be able to converse in Italian, follow instructions regarding the use of portable HPT equipment, have a satisfactory home environment, be able to return to the hospital for follow-up each day after discharge until it was deemed safe to stop, and have no close contact history with any COVID-19-infected person [11], including family members, caregivers, and visitors.

The neonatal phototherapy lamp (MIRA-Ginevri phototherapy lamp ®) uses latest LED technology to produce blue therapeutic light (peak 460 nm) transmitted through a flexible fiber optic cable to a lighting element of small dimensions (area pad efficacy 110 × 160 mm) placed in contact with the skin of the neonate (maximum irradiance of 45 µW/cm2 /nm, according to AAP 2004 Guidelines) [12]. The compact design of this wireless device (3 kg) allows executing the therapy in a straightforward fashion for home care (Fig. 1).

Parents of neonates fulfilling the inclusion criteria were taught how to use the phototherapy equipment, and again informed about the pilot study, the potential harm of hyperbilirubinemia, the importance of bilirubin monitoring, the availability of HPT, and methods for assessing a neonate’s condition. In addition, detailed information about COVID-19 and prevention strategies was provided together with full availability of a telephone call or virtual appointment after infants were discharged home. Signed written consent for HPT use was obtained from parents, who also received a feedback sheet to complete at the end of treatment, with ad hoc questions on the degree of parental satisfaction with additional comments.

The neonatal staff reviewed infants referred from HPT every day, evaluating COVID-19 risks (for the infants as well as their families and caregivers) and the occurrence of inadequate breast milk intake. The staff also measured the body temperature of the infants routinely and performed capillary heel TSB and Hct. Once TSB level was below the treatment threshold (< 75th percentile, low-risk, or low-intermediate-risk zone) of the Bhutani nomogram [10] across two consecutive samples, HPT was stopped, and a rebound level was taken 12–24 h later. If satisfactory, the device and feedback form were collected.

Statistical analysis

We included in the descriptive analysis all infants who received HPT. Patient characteristics (gestational age, gender, birth weight, and cord blood gas analysis investigations: bilirubin, pH, and Hct; age and risk zone at phototherapy initiation) and outcome measures (TSB, Hct, weight loss, and feeding modalities at discharge; duration of phototherapy; readmission age) were summarized with a descriptive purpose using means and standard deviations (continuous data) or frequencies and percentages (categorical data). Data were presented as mean ± SD for normally distributed continuous data and number and % for continuous data. Statistical analysis was performed using R 3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Participants were recruited in a 6-month period, from June to December 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the cohort of 462 infants, 30 (6.5%) met the HPT inclusion criteria and received the allocated HPT intervention. Mothers were 32.10 ± 5.64 years old and 19 (63.3%) were nulliparous. Pregnancy was complicated in 8 (26.7%) by gestational diabetes in 5 (16.7%) treated with diet in 2 and diet and insulin in 3, and by oligohydramnios (1 case), polyhydramnios (1 case), and cholestasis (1 case). Most, 26 (6.6%) delivered vaginally, including 1 (3.33%) neonate instrumentally delivered by kiwi. 4 (13%) were delivered via cesarean. Pre-discharge, on the second day postpartum, 16 (53.3%) neonates were exclusively breastfeeding, 12 (40.00%) were complementary feeding, and 2 (6.66%) were formula feeding.

The anthropometric and clinical features of HPT neonates are included in Table 1.

Of the cohort of 462 infants, 30 (6.49%) met the inclusion criteria. At discharge on the second day of life, TSB was 12.05 ± 1.41 mg/dL, Hct 54.57 ± 6.59%, and weight loss was − 6.56%.

HPT was initiated in 4 neonates with TSB between 75 and 95th percentile (high-intermediate-risk zone) and in 26 neonates with TSB > 95th percentile (high-risk zone) of the Bhutani nomogram [10]. Among these neonates, 27/30 (90%) completed the HPT with a progressive decrease of TSB levels, but 4 neonates required a second course and 3 a third course of 24 h HPT, with a mean HPT duration of 1.37 days. 3/30 (10%) neonates failed HPT and were readmitted after one 24-HPT course for in-hospital phototherapy, 1 with TSB = 95th percentile and 2 with TSB > 95th percentile (high-risk zone) of the Bhutani nomogram [10].

No abnormalities of breastfeeding, body weight control (> 10% decrease) or temperature, nor COVID infections were detected post-HPT consultation in neonatal ward. Overall parental experience of home phototherapy service is reported in Table 2.

The secondary outcome, parental satisfaction, was reported in all but 3 cases, which involved difficulties with the equipment and inconsistent lamp manipulation practices. The responses to the initial questions “Were there any disadvantages to having HPT?” in the questionnaire indicated high levels of satisfaction (27/30, 90%) with the service. Additionally, degree of parental satisfaction regarding “Overall parental experience of HPT service” was good in 24/30 (90%), neutral in 4/30 (13.33%), and bad in 2/30 (6.66%).

In the second part of the questionnaire, in the space provided for additional comments, when parents of neonates readmitted for in-hospital phototherapy were asked about the overall experience of the HPT service, the most common themes in the responses were concerns about being in the home environment with an at-risk neonate, finding HPT too stressful, and experiencing difficulties with the equipment.

Discussion

Owing to rigorous quarantine and infectious control measures taken in maternity wards during the COVID-19 outbreak, management strategies of neonatal jaundice, almost universal in newborn infants, have become challenging when it comes to providing holistic mother-infant dyad-centered care [3]. This pilot study suggests that HPT for neonatal jaundice can be effectively carried out/administered despite the hospital restrictions imposed by COVID-19 waves, with high levels of parental satisfaction with the service. Having parents return with their neonates on a daily basis for follow-up with frontline clinicians in the neonatal ward, who collect relevant information, is worth consideration as a safe and feasible strategy for determining whether to continue or discontinue phototherapy treatment. Such a strategy works in favor of maternal mental health, bonding, and breastfeeding success [5].

HPT has been available in high-income countries for more than 25 years as an alternative to phototherapy in the hospital [3]. Jaundice treatment at home has potential advantages over treatment in the hospital. Disruptions to breastfeeding and parent–infant bonding are minimized at home, whereas in some hospitals, nursery infants may be moved out of the mother’s room for phototherapy, possibly contributing to maternal postpartum psychoemotional distress [4, 5]. Traditional treatment at home may also be more convenient for families, and less costly than hospitalization [4, 5]. However, these assumptions may be related to a paucity of evidence, given that few studies have examined the use of home phototherapy. These studies had small sample sizes or restricted eligibility for HPT, and were carried out with differing follow-up strategies, making it harder to draw meaningful conclusions across studies. Of note, a 2014 Cochrane Review by Malwade and Jardine intending to compare home and hospital-based phototherapy in newborns with non-hemolytic jaundice could not be performed due to insufficient evidence to support or refute the practice of home-based phototherapy for non-hemolytic jaundice in infants more than 37 weeks gestational age [5].

To our knowledge, this is the first cohort study that evaluated the effectiveness of HPT in temporal association with the current COVID-19 pandemic, based on post-phototherapy neonatal clinical status assessed frontline in the neonatal ward together with the lactation skills of the mothers. While a comprehensive economic analysis was outside the scope of this pilot observational study, baseline data from our combined home and hospital service demonstrated the potential efficiency of delivering care in this manner, so as to give people more personalized, supported, and connected care in their own homes, thereby reducing the need for postpartum hospital visits. Although HPT is not suitable for all infants and families, it may be a convenient alternative to IPT as it resulted successful in 90% of jaundiced infants in this study. Among these, ~ 15% of infants required more than one session of HPT and 10% required readmission for IPT due to non-compliance with the treatment protocol in the presence of a high bilirubin risk. Chang and Waite reported a readmission rate of 1.9% [3]. However, they used different treatment thresholds and possibly limited non-adherence to the protocol by having a pediatric nurse travel to the home of the neonates to set up the HPT equipment, weigh the infant, check the TSB level at least daily, and provide lactation support as needed. Reducing readmission rates help reduces maternity bed occupancy in pediatric wards, consequently freeing beds for acutely unwell neonates [14].

Given that this a pilot study, it is unable to compare the features, duration, and efficacy of our portable fiber optic phototherapy to historical or parallel control groups or other modalities to administer phototherapy in-hospital or at home which may vary in the particular wavelength of the light used and/or the intensity of the light source. It is important to note that HPT use among pediatric providers varies depending on which device is used due to differences in spectral power and corresponding PT efficacy [13]. For example, the HPT device used in this study—the MIRA-Ginevri phototherapy lamp—likely had greater PT efficacy compared to some alternative devices given the proximity of the light source to the infant’s skin. There are also several important caveats to consider in evaluating the effectiveness of home phototherapy, as it relies on parental compliance and confidence in use of equipment without constant supervision as well as differing amounts of childcare experience among the parents (depending on how many prior children they had).

Moreover, the hour-specific nomogram developed by Bhutani et al. to predict hyperbilirubinemia risk is quite different from AAP and NICE treatment thresholds [10, 12, 15, 16]. Whereas NICE guidelines offer gestation-specific thresholds at weekly intervals up to 38 weeks, the AAP guidelines offer a composite guideline for infants ≥ 35 week. In addition, although HPT may seem a convenient alternative to in-hospital phototherapy, it is not suitable for infants with very high bilirubin levels or families lacking the ability to return to the hospital daily for follow-up. Nevertheless, measurements of parental satisfaction using appropriately designed and delivered surveys may provide robust quality of care measures and can help improve services and their delivery [16, 17]. Of note, in our cohort, parental feedback on HPT in the questionnaire indicated high levels of satisfaction. Similarly, Jackson et al. reported that all parents were highly satisfied that all information concerning the HPT had been supplied to them. Eighty-five percent found no disadvantages with HPT, but some concerns were expressed. The two main disadvantages were equipment issues, as well as the baby not settling in the HPT unit. A few parents found being responsible for their baby’s care without constant medical supervision anxiety-inducing, and thus did not feel entirely confident. This is relevant, considering that a minority of parents in our pilot study did experience some difficulties with the equipment, such as struggling to put the slipping phototherapy pad on their infants during treatment (1 patient) and non-adherence to protocol (2 patients). Therefore, it would be worthwhile sharing these few reported difficulties, especially equipment issues, with families in advance along with suggestions as to how these difficulties can be overcome, which could further reduce the parental discomfort and anxiety HPT might produce.

In conclusion, this pilot study suggests that HPT for neonatal jaundice can be effectively administered in a select group of infants and also that is viewed very positively by families. The study also proves that HPT can be incorporated in clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. It enables mothers and their infants to remain at home receiving family support as hospital-based phototherapy can be challenging for maternal mental health, breastfeeding initiation, and bonding. Nevertheless, this experience has helped us continue to perform HPT and has led us to consider the possibility of implementing the service with a domiciliary check of TSB. However, the inherent limitations of pilot studies do not make it possible to measure the exact efficacy, satisfaction difficulties, and costs of HPT.

Data availability

Data and material are available in electronic format at the Policlinic Abano Terme.

Abbreviations

- HPHT:

-

Home phototherapy

- TSB:

-

Total serum bilirubin

References

Dennery PA, Seidman DS, Stevenson DK (2001) Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. N Engl J Med 22:581–90. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200102223440807

Szucs KA, Rosenman MB (2013) Family-centered evidence-based phototherapy delivery. Pediatrics 131:e1982–e1985. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3479

Chang PW, Waite WM (2020) Evaluation of home phototherapy for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. J Pediatr 220:80–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.01.004

Chu L, Qiao J, Xu C (2020) Home-Based phototherapy versus hospital-based phototherapy for treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Pediatr 59:588–595. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922820916894

Malwade US, Jardine LA (2014) Home‐versus hospital‐based phototherapy for the treatment of non‐haemolytic jaundice in infants at more than 37 weeks’ gestation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:CD010212. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010212.pub2

Ma X, Zeng Cm Zhu J-J et al (2020) Management strategies of neonatal jaundice during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. World J Pediatr 16:247–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-020-00347-3

Zanardo V, Manghina V, Giliberti L et al (2020) Psychological impact of COVID-19 quarantines measures in northeastern Italy on mothers in the immediate postpartum period. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 150:184–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13249

Yonemoto N, Dowswell T, Nagai S, Mori R (2021) Schedules for home visits in the early postpartum period. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7:CD009326. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009326.pub4

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice (2020) Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping After Birth: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 814 2020 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice. 136:e100-e106. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004167

Bhutani Vk L, Johnson EMS (1999) Predictive ability of a predischarge hour-specific serum bilirubin for subsequent significant hyperbilirubinemia in healthy term and near-term newborns. Pediatrics 03:6–14. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.103.1.6

WHO Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): How is it transmitted? (2021). https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-how-is-it-transmitted. Accessed 23 Dec 2021

American Academy of Pediatrics (2004) Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation, Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia. Pediatrics 114:297–316. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.114.1.297

Tridente A, De Luca D (2012) Efficacy of light-emitting diode versus other light sources for treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 101:458–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02561.x

Noureldein M, Mupanemunda G, McDermott H, Pettit K, Mupanemunda R (2021) Home phototherapy for neonatal jaundice in the UK: a single-centre retrospective service evaluation and parental survey. BMJ Paediatr Open 5:e001027. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Accessed 23 Dec 2021

Nice.org.uk (2021) Recommendations | jaundice in newborn babies under 28 days | guidance | NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg98/chapter/Recommendations. Accessed 30 Mar 2021

Debono D, Travaglia J (2009) Complaints and patient satisfaction: a comprehensive review of the literature. Centre for Clinical Governance Research, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, National Library of Australia. file:///C:/Users/vince/Downloads/literature_review_patient_satisfaction_and_complaints.pdf

Jackson CL, Tudehope D, Willis L, Law T, Venzl J (2000) Home phototherapy for neonatal jaundice–technology and teamwork meeting consumer and service need. Aust Health Rev 23:162–168. https://doi.org/10.1071/ah000162

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the nursery and neonatal nurses, midwives, and the pediatric team at Policlinic Abano Terme for their great contribution to the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VZ helped design the study; was responsible for staff training, study management, and data collection; and took part in data analysis and manuscript writing. PG and LS helped design the study; advised on staff training, study management, and data collection; and took part in data analysis and manuscript writing. PM, GG and CMR helped design the study; advised on staff training, study management, and data collection and analysis; and took part in manuscript writing. AS helped design the study; advised on staff training, study management, and data collection; and took part in data analysis and manuscript writing. GS is guarantors for the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Policlinic Abano Terme Ethics Committee consent was obtained.

Consent to participate

Parents gave informed consent to HPT via signature.

Consent for publication

Parents gave informed consent to publication via signature.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Daniele De Luca

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zanardo, V., Guerrini, P., Sandri, A. et al. Pilot study of home phototherapy for neonatal jaundice monitored in maternity ward during the enforced Italy-wide COVID-19 national lockdown. Eur J Pediatr 181, 3523–3529 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04557-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04557-x