Abstract

Witnessed violence is a form of child abuse with detrimental effects on child wellbeing and development, whose recognition relies on the assessment of their mother exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV). The aim of this study was to assess the frequency of witnessed violence in a population of children attending a pediatric emergency department (ED) in Italy, by searching for IPV in their mother, and to define the characteristics of the mother–child dyads. An observational cross-sectional study was conducted from February 2020 to January 2021. Participating mothers were provided a questionnaire, which included the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and additional questions about their baseline data and health. Descriptive analysis was reported as frequency and percentage for the categorical variables and median and interquartile range (IQR) for quantitative variables. Mothers and children screened positive and negative for IPV and witnessed violence, respectively, were compared by the chi-square test or the exact Fisher test for categorical variables, and by the Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables. Out of 212 participating mothers, ninety-three (43.9%) displayed a positive WAST. Mothers tested positive were mainly Italian (71%, p 0.003), had a lower level of education (median age at school dropout 19, p 0.0002), and a higher frequency of unemployment (p 0.001) and poor personal health status (8.6%, p 0.001). The children of mothers tested positive showed a higher occurrence of abnormal psychological-emotional state (38.7%, p 0.002) and sleep disturbances (26.9%, p 0.04).

Conclusion: IPV was common in a population of mothers seeking care for their children in a pediatric ED.

What is Known: • Witnessed violence is a form of child abuse, usually inferred by their mothers’ exposure to IPV. The latter is suffered by one in three women worldwide. | |

What is New: • This study shows a 43.9% prevalence of IPV among mothers attending an Italian pediatric ED. • Positive mother-child dyads displayed a higher frequency of poor mothers’ health status and children’s abnormal emotional state and sleep disturbances. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), child abuse is among the major global public health issues, representing one of the leading causes of infants’ death in the high-income countries and is estimated to be largely under-recognized [1]. Its consequences on child wellbeing can be both direct (namely physical injuries or death [2]) and indirect, exposing the child to an increased risk of developing psychological, behavioral, social, and medical disorders [3].

Witnessed violence is a form of child abuse, consisting of the child experience of any kind of maltreatment against his/her parents/caregivers/family members, and can be either direct (if the maltreatment takes place in the child presence) or indirect (if the child is aware of the maltreatment and perceives its acute/chronic, physical/psychological effects).

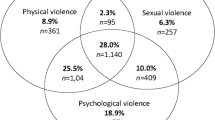

The recognition of children witnessed violence requires the previous assessment of their mothers’ exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV), defined by the WHO as a “behavior within an intimate relationship that causes physical, sexual, or psychological harm, including acts of physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviors” committed by a current or former partner [4]. According to the WHO reports, one in three women is subjected to IPV, and it has been estimated that among children living in households where IPV takes place, 85% are direct witnesses to violence, and up to one half undergo direct forms of abuse, mostly by the father or any other male family member [5]. A European survey showed that 19% of Italian women are physically or sexually abused by their partner and that 38% suffer from repeated psychological maltreatment [6]; among abused women, 65% disclose that their children witnessed one or more episodes of violence [7].

Exposure to IPV not only has deleterious effects on the child wellbeing, and cognitive and socio-emotional development [8], but it also negatively affects behaviors and relationships into adulthood: boys and girls who experience household violence against their mother are at increased risk of perpetuating aggressive behaviors and being victims of domestic violence later in their own lives, respectively, engaging in the so-called intergenerational perpetuation of violence [9].

While the WHO currently recommends screening for IPV during pregnancy [10], no agreement exists on the appropriateness of routine assessments of postpartum IPV. Nevertheless, on the ground of the detrimental effects of IPV on children, the American Academy of Pediatrics advocated for IPV screening in pediatric settings, endorsing the abuse of women as a pediatric issue [11].

Healthcare professionals are generally in a privileged position to investigate IPV; the emergency department (ED) represents an ideal setting to detect abuse and take actions against it [12]. Women’s health studies have shown that victims of domestic violence seek medical attention in ED settings more often than through scheduled appointments with healthcare providers, due to concerns of referral to social services and/or because unable to negotiate with the abuser any other form of access to healthcare facilities for themselves and their children [13]. The pediatric ED, where mothers seek attention with their children often in the absence of their partner, provides a unique opportunity to involve the mother–child dyads in research surveys, in accordance with the international guidelines on research on violence against women and children [14, 15]. Only two studies have investigated IPV in the pediatric ED settings so far, finding a prevalence varying from 11 [16] to 52% [17].

The aim of this study was to assess the incidence of witnessed violence in a population of children attending a pediatric ED, by investigating the prevalence of IPV exposure among their mothers, and to define the demographical and clinical characteristics of the mother–child dyads.

Materials and methods

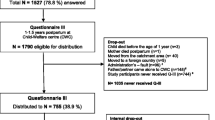

An observational cross-sectional study was carried out at the Institute for Maternal and Child Health of Trieste, Italy, a third-level pediatric teaching hospital, from February 2020 to January 2021. The study was approved by the Institutional review board (RC 14/19).

The pediatric ED refers to a catchment area of 250,000 people and is the only pediatric facility available. Access is open and free of charge, so that children are directly brought to the ED by parents for any medical concern, with only a small percentage admitted by Emergency Services or referred from nearby hospitals. All children are also followed up by a family pediatrician supplied by the national health system without any charge. The pandemic context at the time of the study significantly reduced the number of total accesses to the pediatric ED. Triage codes are assigned according to national guidelines as follows: red (very critical), yellow (moderately critical), green (not very critical), and white (not critical). During the study period, 14,446 children were seen at our PED, distributed as follows: 55 red codes, 1038 yellow codes, 7823 green codes, and 5550 white codes.

All children aged 0 to 17 years attending the pediatric ED, undergoing clinical observation within the ED and/or admission to the ward accompanied by their mother, were considered eligible as a mother–child dyad. The absence of the mother, the inability of the mother to fill in the questionnaire (due to either language barrier or inability to leave the child behind for a while), and the impossibility to take the mother aside from her partner were considered exclusion criteria. The latter was defined according to the arbitrary psychologist judgment in each case, whenever, after several attempts, the approach was perceived as a possible form of pressure and even danger to the mother.

The enrollment was limited to the presence of the enrolling psychologist in the hospital, which took place at random times during the day (from 08:00 to 24:00). The latter introduced the study to the eligible mothers and provided the questionnaire along with information about help resources available for women subjected to IPV.

Given the lack of a validated tool to detect violence witnessed by children, the latter is usually inferred by any abuse of their mother. In this study, mothers’ victimization was assessed through the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) [18]. An Italian version of the latter was validated by four native speaker translators, in full accordance with international recommendations [19]. The WAST is a validated questionnaire assessing women’s physical, psychological, and sexual abuse by their partner in the last 12 months. It comprises eight questions, each with three possible answers, graded from 0 (never) to 2 (often): an overall score of 4 or above suggests women abuse by their partner.

In accordance with the WHO guidelines on research about women and children abuse [6], the WAST items were inserted into a more general questionnaire specifically developed for the aim of the study, including questions regarding the mother’s demographic data, level of education, employment, working time, and health status. The latter was assessed through questions addressing physical injuries, hospital admissions, use of medicines, quality of sleep, level of stress, identified sources of stress, availability of a confident, and self-reported symptoms during the last month including difficulties in sleeping, nightmares, concentration difficulties, decisional skills, ability to overcome difficulties, self-blaming, anxiety, panic attacks, and auditory hallucinations. The above items were selected as measures of the women’s health status, based on previous literature [6]. Answers were either yes/no (e.g., physical injuries, hospital admissions, use of medicines, quality of sleep, stress exposure, identified sources of stress, and availability of a confident), or a 3-point Likert scale describing the frequency of each symptom, graded from never to often (e.g., self-reported symptoms during the last month, including difficulties in sleeping, nightmares, concentration difficulties, decisional skills, ability to overcome difficulties, self-blaming, anxiety, panic attacks, and auditory hallucinations). When possible, the answers were dichotomized or categorized adequately with the help of the psychologist.

Moreover, the items of the WAST were further extended to investigate the presence of physical, sexual, and psychological abuse perpetrated by the women’s own family and the family of their partner. Finally, the questionnaire included a blank space to be filled in by the participating women with a free comment expressing their opinion about the study. The questionnaire was delivered to the mothers in safe circumstances, and they eventually fulfilled it alone in a safe environment.

The data on children were collected by the enrolling physician and included the patient’s sex, age, baseline medical disease, number of ED attendances in the last 12 months, diagnosis at discharge, and emotional state at the time of the discharge from the ED (normal/excessively calm/anxious/aggressive). The definitions of “normal,” “excessively calm,” “anxious,” and “aggressive” were discussed in a pre-study meeting with the ED staff. According to the study protocol, the psychologist was not allowed to exchange opinions with the ED doctor before his/her evaluation. However, if an obvious concern about a risk situation for the mother–child dyad was raised, a communication between the two was allowed at the end of each evaluation.

To allow anonymity, every enrolled mother–child dyad was identified through a consecutive number, which was affixed to both the child’s data collecting sheet and the mother’s questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Expecting a prevalence of children witnessed violence of 15%, considering a level of significance of 5% and a precision of 5%, the minimal size of the sample was set at 196 children. Prevalence of witnessed violence was expressed as the proportion of children whose mothers tested positive for IPV according to the WAST score and the total number of enrolled children. The descriptive analysis was reported as frequency and percentage for the categorical variables and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for quantitative variables. Mothers and children tested positive and negative for IPV and witnessed violence respectively were compared by the chi-square test or the exact Fisher test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 212 mother–child dyads were considered eligible for participation in the study. During the study period, the pediatric ED of our Institute was applying measures to control the spread of COVID-19; thus, each child was allowed to be accompanied by only one parent: therefore, all the attending mothers were unaccompanied by their partner and no one of the eligible women was excluded from participation in the study. Remarkably, none of the mothers who were proposed to take part in the survey refused to participate, and all completed the questionnaire entirely. One hundred forty-one women (66.5%) fulfilled the blank space of the questionnaire with their opinion about being involved in the research, expressing high appreciation in all cases.

Out of 212 participating mothers, 43.9% displayed a positive WAST test (Table 2). The demographical characteristics of the enrolled mothers are reported in Table 1. Table 2 summarizes the study findings regarding the mothers’ population. The demographical characteristics and the study findings on the children population are reported in Table 3.

Discussion

This study shows a 43.9% prevalence of IPV among mothers attending a pediatric ED, and likely a similar exposure to witnessed violence among their children. To our knowledge, only two previous studies investigated this issue in the same setting [15, 16]: while consistent with the previous finding by Newman et al. (52%) [16], the prevalence of IPV in this sample is considerably higher than the following observation by Randell et al. (11%) [15]. However, the study period coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought to an escalation of domestic violence worldwide [20]. In Italy, comparing the period between March and June 2020 with the same period of the previous year, a rise of the 73% in the number of help-seeking calls for violence has been observed, taking place at home in 93.4% of cases and being witnessed by children in 64.1% [21].

Comparing women with positive and negative WAST, no statistically significant difference was noted in terms of mothers’ age: while younger women are traditionally considered at higher risk of abuse compared to older women, more recent findings denied this association [21], reflecting the universal trend towards a more transversal diffusion of domestic violence. Similarly, in contrast with previous literature [22], no differences were found in the frequency of IPV when considering marital status. In accordance with previous findings, no differences were observed in the number of children per woman [23]. This study showed a higher incidence of IPV in Italian mothers, confirming the previous observation that pertaining to ethnic minorities does not constitute a risk factor for abuse [20]. The only statistically significant differences in terms of baseline characteristics between IPV and non-IPV-subjected women in this study were the lower age at school withdrawal in abused mothers (confirming the previous finding by Randell et al. [15]) and the higher rate of unemployment and part-time jobs.

The use of the WAST items to assess the relationship with the partner’s family showed that women who screened positive faced significantly more tensions with the partner’s family members compared to women screened negative. Interestingly, the same difference was noticed when examining the relationship with members of their own family, supporting previous observations on the intergenerational perpetuation of violence [9].

Significantly more mothers in the positive group self-reported poor personal health status compared to the negative group, disclosing a higher level of stress, and a higher frequency of autonomic and psychological disorders, including sleep disturbances, self-reported anxiety and depression, and physical injuries. This data is in accordance with previous literature, showing an association of poor maternal psychological [24] and physical [25] health with both recent and past IPV [26]. Nevertheless, no difference was observed between IPV and non-IPV mothers in terms of frequency of hospital admissions, confirming the findings by Newman et al. [16] and Randell et al. [15]. These authors observed that abused mothers reported seeking care in the ED for child-related issues twice as often as for their own health issues: this underscores the opportunity offered by the pediatric ED settings to screen for IPV.

In the current study, mothers in the positive and negative group were equally concerned about the possible impact on their child wellbeing of the difficulties in the relationship within the couple or with other family members. This data confirms the previous observation by Duffy, in whose study half of the surveyed mothers expressed their concern about the emotional effect of violence exposure on their children [16].

As far as children are concerned, the negative outcomes of IPV on physical growth and development are well known [8, 27, 28], including a greater frequency of internalizing and externalizing behaviors [29, 30]. Accordingly, in the present study, a higher frequency of abnormal psychological-emotional status at the time of the pediatric ED attendance was displayed by children screened positive for violence exposure compared to the negative group, together with a higher frequency of sleep disturbances. Consistent with the findings by Newman et al. [16] and Randell et al. [15], no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups of children tested positive and negative for witnessed violence, in terms of frequency of chronic baseline conditions and types of diagnosis at discharge. However, psychiatric diagnoses were three times more common in the positive group than in the negative group. The lack of identifying markers of violence in children’s conditions strengthens the need for routine screening for violence exposure, to interrupt the cycle of violence.

This study has several limitations. Enrollment relied on the presence of an enrolling psychologist in the hospital, which was limited to daytime. Due to the anonymous collection of data, we could only rely on mothers’ reports of their symptoms and were therefore unable to assess the frequency of psychological as well as medical disorders in the participating women. For the same reason, we were not able to investigate the presence of baseline psychiatric diagnoses in the children population. Children’s emotional state at the time of discharge from the ED was evaluated by the blind ED physicians on the ground of their experience, and no validated tool was used. Similarly, while the medical condition and/or undergone procedures may have interfered with the child’s emotional expressions, this was not formally addressed through a dedicated tool, but simply endorsed by the ED physician when evaluating the child’s emotional state. Another limit is that the nurses’ opinion and evaluation of the child’s emotional state was not considered. Moreover, children exposure to witnessed violence was inferred from IPV, and we did not directly assess it from children able to be interviewed. The points of strength included its prospective design, the unique dedicated enrolling psychologist with experience in the field of IPV, the high rate of mothers’ participation in the study, the use of a standardized validated questionnaire, and the time gap with the only two similar previous studies (dated back to 1999 [16] and 2005 [15]).

Conclusion

This study shows that IPV is common in a population of mothers seeking care for their children in a pediatric ED. The high rate of participation in the study confirms that validated screening tools like the WAST are useful and well accepted by women. The lack of differences in terms of demographical characteristics of the participating women, as well as baseline and acute diagnoses in their children, supports the need for a widespread screening application and awareness by healthcare professionals.

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- IPV:

-

Intimate partner violence

- WAST:

-

Woman Abusive Screening Tool

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB (2002) The world report on violence and health. Lancet 360(9339):1083–1088

Ackerson LK, Subramanian SV (2009) Intimate partner violence and death among infants and children in India. Pediatrics 124(5):e878–e889

Gilbert R, Spatz Widom C, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S (2009) Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 373(9657):68–81

World Health Organisation (2010) Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: Taking action and generating evidence. World Health Organisation Geneva

World Health Organization (WHO) (2014) Global Status Report on Violence Prevention

Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) (2014) Violence against women: an EU-wide survey

ISTAT (2015) La violenza contro le donne dentro e fuori la famiglia

Gilbert AL, Bauer NS, Carroll AE, Downs SM (2013) Child exposure to parental violence & psychological distress associated with delayed milestones. Pediatrics 132(6):E1577–E1583

Maxfield M, Widom C (1996) The cycle of violence, revisited 6 years later. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 150:390–395

World Health Organization (2013) Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect (1998) The role of the pediatrician in recognizing and intervening on behalf of abused women. Pediatrics 101:1091–1092

Teeuw AH, Derkx BHF, Koster WA, van Rijn RR (2012) Educational paper: Detection of child abuse and neglect at the emergency room. Eur J Pediatr 171(6):877–885

Abbott J, Johnson R, Koziol-McLain J, Lowenstein SR (1995) Domestic violence against women: incidence and prevalence in an emergency department population. JAMA 273:1763–1767

World Health Organization (2001) Global Programme on Evidence for Health Policy. Putting women first: ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. World Health Organization

Randell KA, Sherman A, Walsh I, O’Malley D, Dowd MD (2021) Intimate Partner Violence Educational Materials in the Acute Care Setting: Acceptability and Impact on Female Caregiver Attitudes Toward Screening. Pediatr Emerg Care 37(1):e37–e41

Newman JD, Sheehan KM, Powell EC (2005) Screening for intimate-partner violence in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 21(2):79–83

Duffy SJ, McGrath ME, Becker BM, Linakis JG (1999) Mothers with histories of domestic violence in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics 103(5 Pt 1):1007–1013

Brown JB (2000) Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-Short in the Family Practice Setting. J Fam Pract 49(10):896–903

Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat J (2011) Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract 17:268–274

Hamadani JD, Hasan MI, Baldi AJ, Hossain SJ, Shiraji S, Bhuiyan MSA et al (2020) Immediate impact of stay-at-home orders to control COVID-19 transmission on socioeconomic conditions, food insecurity, mental health, and intimate partner violence in Bangladeshi women and their families: an interrupted time series. Lancet Glob Health 8(11):e1380–e1389

ISTAT (2020) Violenza di genere al tempo del Covid-19: le chiamate al numero di pubblica utilità 1522. https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/242841

Siddique JA (2016) Age, Marital Status, and Risk of Sexual Victimization: Similarities and Differences Across Victim-Offender Relationships. J Interpers Violence 31(15):2556–2575

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Wattset CH (2006) Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet 368(9543):1260–1269

Fowler JC, Allen JG, Oldham JM, Frueh BC (2013) Exposure to interpersonal trauma, attachment insecurity, and depression severity. J Affect Disord 149(1):313–318

Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, Kub J, Schollenberger J, O’Campo P et al (2002) Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch Intern Med 162:1157–1163

Brown SJ, Conway LJ, FitzPatrick KM, Hegarty K, Mensah FK, Papadopoulloset S et al (2020) Physical and mental health of women exposed to intimate partner violence in the 10 years after having their first child: an Australian prospective cohort study of first-time mothers. BMJ Open 10:e040891

Neamah HH, Sudfeld C, McCoy DC, Fink G, Fawzi WW, Masanja H et al (2018) Intimate partner violence, depression, and child growth and development. Pediatrics 142(1):e20173457

Jeong J, Adhia A, Bhatia A, McCoy DC, Yousafzai AK (2020) Intimate Partner Violence, Maternal and Paternal Parenting, and Early Child Development. Pediatrics 145(6):e20192955

Chander P, Kvalsvig J, Mellins CA, Kauchali S, Arpadi SM, Tayloret M et al (2017) Intimate partner violence and child behavioral problems in South Africa. Pediatrics 139(3):e20161059

Westrupp EM, Brown S, Woolhouse H, Gartland D, Nicholson JM (2018) Repeated early-life exposure to inter-parental conflict increases risk of preadolescent mental health problems. Eur J Pediatr 177(3):419–427

Acknowledgements

We thank Alessandra Knowles, Martina Bradaschia, Sarah Sciacca, and Anna Lucia Sciacca, for the validation of the Italian version of the WAST questionnaire.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CG conceived the work; FA and GM collected the data; MG performed the statistical analysis; LCW wrote the first draft of the manuscript; PR contributed to the design of the study and to the development of the questionnaire, and provided major inputs to the manuscript drafting; AA and EB edited the final version of the work. All authors approved the manuscript and take full responsibility for its contents.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Institutional review board of the Institute for Maternal and Child Health of Trieste, Italy (RC 14/19).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Piet Leroy.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anastasia, F., Wiel, L.C., Giangreco, M. et al. Prevalence of children witnessed violence in a pediatric emergency department. Eur J Pediatr 181, 2695–2703 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04474-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04474-z