Abstract

Many countries now have guidelines on the clinical management of acute otitis media. In almost all, the public health goal of containing acquired resistance in bacteria through reduced antibiotic prescribing is the main aim and basis for recommendations. Despite some partial short-term successes, clinical activity databases and opinion surveys suggest that such restrictive guidelines are not followed closely, so this aim is not achieved. Radical new solutions are needed to tackle irrationalities in healthcare systems which set the short-term physician–patient relationship against long-term public health. Resolving this opposition will require comprehensive policy appraisal and co-ordinated actions at many levels, not just dissemination of evidence and promotion of guidelines. The inappropriate clinical rationales that underpin non-compliance with guidelines can be questioned by evidence, but also need specific developments promoting alternative solutions, within a framework of whole-system thinking. Promising developments would be (a) physician training modules on age-appropriate analgesia and on detection plus referral of rare complications like mastoiditis, and (b) vaccination against the most common and serious bacterial pathogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: the challenge of marginal efficacy

Otitis media (OM) is a very common childhood infection of the middle ear facilitated by seasonal respiratory viruses. Incidence peaks between 6 months and 2 years, by which age over 90% of children have had at least one episode of acute OM (AOM) [72]. A proportion will develop OM with effusion (OME), with consequences which reach well into mid-childhood [53]. AOM is generally self-limiting, but its recurrence and frequency entail high direct healthcare costs [50] and indirect costs for parents [42], as well as burden on family quality of life [14]. Despite a superficial familiarity, OM still poses many challenges of definition, assessment, and indications for treatment.

Even with insensitive traditional culture methods, about 70% of middle ears in AOM yield bacterial isolates [96], so most of properly diagnosed (and severe) AOM is seen as bacterial [55, 67]. Over-inclusive diagnosis by non-specialists may result in antibiotic prescribing for conditions that are not actually bacterial. Routine microbiological assessment (by paracentesis) is impractical and mostly thought unethical. Hence, antibiotics give frustratingly small benefits [39, 56, 61] compared to temporizing care with analgesics [88]. Even with appropriate diagnosis, the overall clinical effectiveness of antibiotics remains low for reasons which are now well understood, including: poor penetration into the middle ear mucosa [19]; inaccessibility of bacteria in the form of biofilm [48]; little symptomatic benefit in the first 24 h [39, 86]; generally favorable clinical course in most patients if untreated [84]; and poor adherence to treatment regimens [15]. The treatment dilemma is intensified by the emergence of strains resistant to antibiotics [9], which has become the main stimulus to guidelines, discussed further below.

Recent reductions in consultations for AOM [78, 102, 103] are too large and pervasive to be due to one single factor. Guidelines must have contributed, in part, to “de-medicalization” of AOM. The exact contribution of changes in clinical practice and health systems are hard to distinguish so guidelines are best seen as flags of a trend rather than the root cause. Trials suggest that the contribution of pneumococcal vaccination to all-cause reduction in OM is no more than modest [18, 28, 80] and observational studies on all-cause OM consultations post-vaccine are poorly controlled for background trends like the de-medicalization from guidelines [93]. Reduction in the more serious (and more clearly diagnosable) pneumococcal OM is not in question.

Antibiotic prescription rates per consultation for AOM remain high in most countries (approximately 80% of all consultations) [102], and especially in children <2 years [72]. This may be due to a fixed notion of an appropriate prescription rate. Parents’ criteria for consultation may have become both higher and narrower (family-level triage) making more consultations justify a prescription. A further possibility is time pressure as an opportunity cost: the relatively modest cost to the healthcare system of many antibiotics, against the personnel cost for assessment and explanation required in rational prescribing, create an incentive to over-prescribe. The multiple possible explanations for stable prescription rates per consultation amid reduced consultations add to the present requirement for a whole-system examination of the main policy dilemmas around antibiotics in OM, separate from mere promotion of guidelines.

Antibiotic resistance—the driver for change

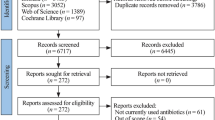

At recent rates of spread of resistance, the low rate of discovery of new antimicrobials will soon compromise mankind’s ability to fight serious infections, including prophylaxis to control infection during surgery [58, 101]. Bacteriological time series data reflect the selection pressures for the development of antibiotic resistance. The European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption findings from 2001 [40], replicated in 2004 [97], established firmly the link between antibiotic consumption and resistance. Countries can be at differing phases of a cycle in consumption and bacterial response [29]: rates of resistance have been rising in Ireland and Finland, but remain low in Germany and The Netherlands. Encouragingly, reducing prescription rates in France, Belgium, and Spain, (former) high-consumption countries, seem to be giving lower levels of resistance (Fig. 1) [29].

Trends between 1999 and 2007 in penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae by country. Reproduced with permission from European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System Annual report 2007 [29]. Available at: http://www.earss.rivm.nl. Data retrieved February 2009. Each bar represents the findings from a single year. The arrows indicate the significant trends observed for all resistant strains (black arrows) or fully penicillin-resistant strains (red arrows). The stars indicate significant trends in the overall national data that were, non-significantly, supported by data from laboratories reporting all 9 years. IE Ireland, IL Israel, IT Italy, BE Belgium, NL Netherlands, DK Denmark, FI Finland, FR France, DE Germany, ES Spain, SE Sweden, UK United Kingdom

OM is a major public health issue because it is a prime target for rational prescribing [24]. It dominates antibiotic consumption, even in low-consumption countries with low OM concern [87]. Secondly, the high incidence and low antibiotic efficacy in OM favor mutation and survival of resistant strains. In infants <2 year, 90% of antibiotic prescriptions are for OM [72], and the number and proximity of contacts in child day care create a particularly effective “forcing ground” for the spread of resistance [43], reflected in locally differing prescription rates for OM [6]. Thus OM particularly justifies guidelines and related developments to restrict prescribing.

Guidelines: formulation and presentation

Guidelines on management of AOM (and of upper respiratory tract infections more generally) draw on shared evidence and clinical insights from a coherent literature. They recommend “watchful waiting” in children >2 years with uncomplicated AOM, and limit immediate prescription to those most likely to benefit, i.e., the very young and those with a firm diagnosis (Table 1). All guidelines stratify eligible patients by age, duration, and severity, although the recommended cut-offs differ between countries. These details are probably less important than whether a guideline recommends watchful waiting as an option or as favored good practice: for example in the child over 2 years and severely ill or still symptomatic after 48 h, in North America antibiotics are “recommended” whereas in Europe antibiotics are “optional”. Feedback and/or sanctions on prescribing practice should be more influential than a recommendation versus an option. Particular clinical options tend to be exercised if the alternative is perceived as therapeutically inactive [18, 46, 62] and naming is an important part of marketing. The professional term (“watchful waiting” or equivalent) guides physician behavior, but may not reduce parental concerns: “age-appropriate analgesia with active monitoring” would more judiciously reassure parents.

Are guidelines alone effective in changing practice?

Evidence-based recommendations are necessary, but insufficient drivers of change. Within an intervention study, short-term performance improvements (reductions in antibiotic prescribing) can be shown, without apparently compromising parental satisfaction [18, 62, 63]. However, where physicians know their performance is observed, such “Hawthorn effects” [38] are expected. This highly controlled evidence shows feasibility and non-harm of rational prescribing, but does not guarantee long-term adherence to guidelines.

There remain wide variations in antibiotic prescribing across Europe [27, 31, 97] and between Europe and the USA [40], with growing consumption and high resistance in Asia [90]. The important global question is therefore whether guidelines will make a large enough difference soon enough. This urgency requires the analysis of policy options broader than dissemination of guidelines, particularly supplementary actions that may help adherence. Guidelines are alien to much medical tradition, but other pressures for change in physician role are occurring for separate reasons, e.g., partnership with, and explanation to, patients. With a judicious lead and explanation, parents can change their expectations and behavior, assisting compliance with guidelines [32, 33]. Effective implementation of guidelines on any condition can require physicians to give advice based on the limited efficacy or unfavorable benefit-to-harm ratio of whole groups of medicines [66]. In the present phase of transition to more patient-centered practice, progressive explanation of more appropriate antibiotic use requires the complementary use of age-appropriate pain management, following a more traditional model of practice. It is surprising that explicit analgesic alternatives have been little developed, promoted, or trialed.

Reasons for non-adherence

Non-adherence to guidelines is based on the clinical predicament as experienced by physicians, not on reasoned counter-claims that guidelines’ aims are somehow inappropriate. The literature (e.g., Cabana [17]) identifies seven overlapping classes of reason for poor adherence, many of them cultural, physician inertia, lack of appropriate incentives, lack of detailed knowledge due to poor dissemination, conflict of interest, parental pressure, insufficient use of appropriate analgesia, uncertain diagnosis, and concerns over possible complications from not treating infection. Different types of policy response are required by reasons based on (a) practical obstacles, (b) clinical counter-arguments that may be part-justified, and (c) veiled excuses not to practice effectively or reflectively.

Multi-dimensional cultural differences and the vicious spiral

Major differences exist between countries in medical beliefs and practices [74] for economic and cultural reasons. Compared to Northern and Western Europe, Southern and Eastern European countries have greater use of antibiotics [41]. The very low (until recently) antibiotic prescription rate for AOM in the Netherlands for OM [34], has been offset by a high rate of early surgical intervention, often for recurrent AOM rather than OME. The Franco-German contrast between two generally similar countries shows how cumulative differences in health beliefs, social determinants, and regulatory practice produced in France a rate of antibiotic consumption twice that of Germany [49]. Such accumulations of several factors [85] resist change if they are mutually reinforcing, forming vicious spirals (Fig. 2). But a spiral can also permit large changes, if any of the links become greatly weakened, e.g., the belief in high efficacy of antibiotics for AOM.

Parental pressure: the burden of OM on the family

Breaking the spiral requires acknowledgement of the range of impacts of OM on the family (absence from work with possible loss of earnings, extra childcare, loss of family quality of life, and lowered resilience of the parents to cope with other problems) [14]. These have not so far been summarized in a single index, but pressures for consultation and antibiotic use do reflect these impacts, and so carry implications for the economic and other choices being modeled. When watchful waiting was incorporated by Meropol et al. [65] in a formal decision analysis, it was suggested that work days lost by parents of children older than 2 years (compared with <2), due to prolonged episodes of OM, could pose a genuinely grounded policy obstacle to rational prescribing.

Physician inertia

Databases on actual clinical activity [3, 81, 83] and surveys of clinician opinion or professed practice [1, 37, 57, 99] show poor adherence to guidelines in the real world [82], making it unlikely that repeating summaries of evidence can achieve desired changes. One aspect of this inertia is shift in diagnostic habit, concealing discrepancies between recommended practice and actual prescribing behavior. Some displacement of former AOM into the separate diagnosis of OME was noted in the UK [95, 102] recently illustrating the contradictions of performance management. (Antibiotics are even less effective in OME, so rarely used, and not subject to the same guideline strictures.)

Conflicts of interest

In some healthcare systems, a patient/parent can easily change physician and/or consult more than one practice. In combination with payment by item of service, these arrangements make it difficult for physicians to challenge patient health beliefs [89] and intensify the conflict of interest between present doctors or parents (to prescribe) and future patients (to withhold). The conflict becomes extreme in countries where poorly paid doctors receive a commission on drugs prescribed.

Fears over the adverse consequences of restricted prescribing

OM is not zero-risk: some AOM cases progress to complications such as mastoiditis and intracranial abscess. However, any recent increase in acute mastoiditis with restraints on prescription is uncertain from the low event rate and is too small to form a valid objection to guidelines [94]. The prevention of mastoiditis by routine antibiotic treatment of AOM has not been directly established [98]. Thompson and colleagues (2009) showed in a reference population of 2.6 million that, although antibiotics roughly halved the risk of mastoiditis, two-thirds of mastoiditis cases did not have a known antecedent OM [94]. Thus the estimated number-needed-to-treat to prevent one episode of mastoiditis, is unacceptably high [94] and routine antibiotic use may even mask mastoiditis. Physicians and public emphasize the avoidance of serious complications, so progress here requires not merely revisiting the wording of guidance, but support for an alternative action: training and dissemination to encourage prompt referral of suspected mastoiditis to specialists.

Diagnosis of OM versus severity and persistence of disease

General practitioners are broadly aware of the distinction between bacterial and viral infection [16]. In children’s ear problems, such awareness does not seem to restrain antibiotic prescription, perhaps because the known viral facilitation does not rule out bacterial origin or bacterial development (the prophylactic attitude to mastoiditis being one extreme). The uncertainties here make the etiological assumption, (hence antibiotic prescription) culturally arbitrary [25]. Until a low-cost non-invasive method to distinguish bacterial from viral etiology in OM becomes available, pragmatic guidelines cannot handle this issue satisfactorily.

Diagnosis of AOM by physicians is currently suboptimal, with both false-positive and false-negative errors [76]. But this is only the first step to treatment. Proportionate clinical response to the severity and persistence/recurrence of OM is required. In epidemiological research this nuancing only arrived in 1997 for AOM [4] and 1993 for OME [91]. To cater simply for single-episode diagnosis and treatment, AOM guidelines have not adequately addressed the gradation issue [48] and the necessary evidence base for it has not been seriously sought. Proportionate response to severity and recurrence requires integrating information over time, hence either high linkage and accessibility of clinical data or long-term knowledge of the child and family, or both. In the present transitional era, neither can be assumed.

Possible contributions to a solution

Given these obstacles, various policy elements must be considered for reducing resistance.

Risk factor reduction

Guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) have encouraged prevention of OM through reducing modifiable risk factors. Theoretically, there is some scope for reducing the size and influence of the core transmission group [26] via limited use of day care or small groups; breast feeding beyond 3 months protects against risk for early OM [5]. However, risk factor intervention in recurrent AOM meets limited parental willingness to change behavior [13, 65]. Given (a) the general difficulty in changing health-related behaviors by education, (b) the fact that some risk factors are already subject to public health advice, and (c) the modest relative risk values for single factors, risk modification is not generally promising.

Training and role evolution for physicians

A large body of research on guideline implementation [8, 12, 37] identifies the most effective forms and channels of information when updating practice [12, 60]. But healthcare systems are not mechanistic sets of processes that can be enduringly optimized: over-use of particular media degrades their influence with time. For details within conventional medical paradigms (e.g., which specific antibiotics are appropriate for first- and second-line management in a particular setting), physician update education has seemed effective [77]. To support more radical change adequately, issues need to be grouped into packages important enough to command attention and a well-developed educational component then rolled out, as in France where one package improved guideline acceptance [45] and reduced antibiotic resistance.

De-medicalization (helping patients find alternative non-medical solutions) has not been a natural role for physicians. However, the era of the physician as part educator of the patient and especially as the moderator of other information sources (such as the internet) began 20 years ago in advanced countries. Evaluations are beginning to appear of ways within CME to train this educational role of physicians [54]. Major recent changes in the management of chronic conditions may offer principles and precedents for preparing of materials and procedures that “work”.

Decision support

A new habit may be more readily adopted when supported by a facility that solves an acknowledged problem; here information technology offers possibilities. Evidence on reminders and prompts built into computerized decision support systems suggests at least short-term reductions in antimicrobial use and improved appropriateness of antimicrobial selection [60], but feedback on performance against target rates may be more important.

Incentives and related structural changes to manage care

Where healthcare is funded by co-payment systems, financial incentives to patients can be built in or removed. Despite some evidence of incentives changing clinical practice [22], revising payment structures takes resources, and creates complexities needing to be consolidated or removed later. Incentives to doctors may have unforeseen consequences (currently insufficiently researched) such as the erosion of professional motivation towards appropriate and cost-effective practice. Alternative responsibility structures such as pharmacist-led collaborative care, despite some evidence of effectiveness towards rational prescribing [60] may not be politically realistic.

Public information campaigns

In Iceland [7] and USA [100] correlations have been shown between physicians’ practices and knowledge or attitudes about OM. But what is cause and what is effect here? Various education campaigns (international, national, regional, and practice-level) including the recent “European Antibiotic Awareness Day” have improved public knowledge on antibiotic prescribing, but when used in isolation have not changed attitudes nor prescribing practice [52, 64, 73, 92]. The evidence for effectiveness of non-targeted campaigns is at best equivocal [60]. In contrast, assessment of attitudes informed directly by the physician shows improved compliance [8].

Vaccination

Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) and Streptococcus pneumoniae account for approximately 80% of OM cases worldwide [44], with NTHi becoming the new frontier as pneumococcal vaccination spreads [98]. These two pathogens are responsible for the more severe forms and sequelae of OM, so effective vaccination against them could materially reduce OM’s clinical impact and wider burden [68, 75]. Where antibiotic consumption and other health costs for childhood OM are high, the cost-saving argument for vaccination explicitly against OM is already in place. Where antibiotic consumption is low, the vaccination scenario is more complex: cost-savings would need to be accumulated over several disease categories associated with the two main OM pathogens [44, 59] and the benefits, including indirect protection, may need to be measured and accumulated over the severities and prevalences of these same categories.

The conjugate heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine, PCV7 (7vCRM, Prevnar™/Prevenar™), was introduced primarily to prevent invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD: sepsis, meningitis, pneumonia, and bacteraemia) by universal vaccination of infants [79], and it appears in some countries to also benefit adults through herd protection. The large reduction in IPD was accompanied by a small reduction in all-cause OM, this via a moderate reduction in pneumococcal OM [10, 11, 51]. To be described as “for” OM, i.e., effective against most of the most severe OM, a vaccine would also require good coverage of pneumococcal serotypes and of NTHi. An innovative formulation (PhiD-CV, prototype of the recently licensed Synflorix™) has shown significant efficacy against AOM from both NTHi and S. pneumoniae pathogens [21, 80]. Further trials are currently assessing its effectiveness more fully. PCV7 introduction led to a shift in the level of acceptable IPD risk in febrile children, with implications for reduced healthcare use [35]. Further such shifts in risk perception could help dismantle the vicious spiral, by giving confidence not to prescribe prophylactically against rare complications [47]. There is already preliminary evidence in OM that presence of a vaccination program confers such confidence: 3 years after introduction of PCV7 in France, antibiotic consumption, as well as carriage of both resistant and non-resistant strains were reduced in vaccinated children [20]. Prescribing is the chief selection pressure in the bacteriological changes post vaccination, so to further encourage rational prescribing at introduction of vaccines must slow the need for updating them [30]. To provide further evidence for policy decisions, opportunities should be seized for 2 × 2 studies, powered for a more-than-additive combination of introducing vaccination with new (or re-issued) guidelines. This could provide the desired direct evidence for the probable positive synergy between vaccination and rational prescribing policies against antibiotic resistance.

Conclusions

Adherence to guidelines for rational prescribing in AOM has been poor, so mere existence of guidelines has not reduced prescription rates sufficiently or enduringly. Policy initiatives have to directly attack the clinical rationales that permit continuing physician inertia. Immediately, the following three steps would help to break the vicious spiral of antibiotic resistance:

-

Strengthening physician education, training, and continuing professional training towards prevention and explanation, integrated with clinical decision support and feedback; also encouraging continuity of care to manage irrational demand downwards, while providing assurance and monitoring risk

-

Two specific training modules for generalist pediatricians and family practitioners promoting age-appropriate analgesia and the efficient early identification and management of symptomatic mastoiditis

-

Vaccination against the most serious pathogens for OM, shifting the clinical emphasis away from prophylaxis against serious complications, and from low-effectiveness, especially in high-prescription countries of older first-line treatments. The shift in perceived risk following high-coverage vaccination against OM should help to break the vicious spiral, but opportunities should be seized to test this conjecture, and to document the a priori partnership whereby improved adherence to guidelines would decrease replacement pressures and so ease the vaccine development and updating cycle

Abbreviations

- OM:

-

Otitis media

- AOM:

-

Acute otitis media

- OME:

-

Otitis media with effusions

References

Adeli M, Bender MJ, Sheridan MJ, Schwartz RH (2008) Antibiotics for simple upper respiratory tract infections: a survey of academic, pediatric, and adult clinical allergists. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 100:377–383

Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé (2005) Antibiothérapie par voie générale en pratique courante dans les infections respiratoires hautes octobre. Available at: http://www.afssaps.fr/

Akkerman AE, Kuyvenhoven MM, van der Wouden JC, Verheij TJ (2005) Analysis of under- and overprescribing of antibiotics in acute otitis media in general practice. J Antimicrob Chemother 56:569–574

Alho OP (1997) How common is recurrent acute otitis media? Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 529:8–10

American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media (2004) Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 113:1451–1465

Arason VA, Kristinsson KG, Sigurdsson JA et al (1996) Do antimicrobials increase the carriage rate of penicillin resistant pneumococci in children? Cross sectional prevalence study. BMJ 313:387–391

Arason VA, Sigurdsson JA, Kristinsson KG et al (2005) Otitis media, tympanostomy tube placement, and use of antibiotics. Cross-sectional community study repeated after five years. Scand J Prim Health Care 23:184–191

Arnold SR, Straus SE (2005) Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices in ambulatory care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD003539

Arri SJ, Fluegge K, Mueller U, Berner R (2006) Antibiotic resistance patterns among respiratory pathogens at a German university children’s hospital over a period of 10 years. Eur J Pediatr 165:9–13

Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B et al (2000) Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Northern California Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J 19:187–195

Bechini A, Boccalini S, Bonanni P (2009) Immunization with the 7-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine: impact evaluation, continuing surveillance and future perspectives. Vaccine 26:3285–3290

Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM et al (1998) Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. BMJ 317:465–468

Bexell A, Råstam L, Isacsson SO, Ingvarsson L (1990) Parents’ response to recurrent middle ear infection in their children. Scand J Soc Med 18:25–30

Boruk M, Lee P, Faynzilbert Y, Rosenfeld RM (2007) Caregiver well-being and child quality of life. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 136:159–168

Brixner DI (2005) Improving acute otitis media outcomes through proper antibiotic use and adherence. Am J Manag Care 11(6 Suppl):S202–S210

Butler CC, Rollnick S, Kinnersley P et al (2004) Communicating about expected course and re-consultation for respiratory tract infections in children: an exploratory study. Br J Gen Pract 54:536–538

Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR et al (1999) Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 282:1458–1465

Chao JH, Kunkov S, Reyes LB et al (2008) Comparison of two approaches to observation therapy for acute otitis media in the emergency department. Pediatrics 121:e1352–e1356

Coates H, Thornton R, Langlands J et al (2008) The role of chronic infection in children with otitis media with effusion: evidence for intracellular persistence of bacteria. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 138:778–781

Cohen R, Levy C, de La Rocque F (2006) Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and of reduction of antibiotic use on nasopharyngeal carriage of nonsusceptible pneumococci in children with acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J 25:1001–1007

Croxtall JD, Keating GM (2009) Pneumococcal polysaccharide protein d-conjugate vaccine (Synflorix; PHiD-CV). Paediatr Drugs 11:349–357

Danish Integrated Resistance Monitoring and Research Programme (DANMAP) Report (2001) Consumption of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from food animals, foods, and humans in Denmark. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Veterinary Laboratory Available: http://www.danmap.org/pdfFiles/Danmap_2001.pdf. Accessed March 2009

del Castilloa F, Delgado Rubio A, Rodrigo C et al (2007) Asociación Espaňola de Pediatria Consenso Nacional sobre otitis media aguda. An Pediatr (Barc) 66:603–610

Demachy MC, Faibis F, Artigou A et al (2004) Epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated in Ile de France area during 2001. Med Mal Infect 34:303–309

Deschepper R, Vander Stichele RH, Haaijer-Ruskarnp FM (2002) Cross cultural differences in lay attitudes and utilisation of antibiotics in a Belgian and Dutch city. Patient Edue Couns 1590:1–9

Dewey C, Midgeley E, Maw R (2000) The relationship between otitis media with effusion and contact with other children in a British cohort studied from 8 months to 3 1/2 years. The ALSPAC Study Team. Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 55:33–45

Elseviers MM, Ferech M, Vander Stichele RH et al (2007) Antibiotic use in ambulatory care in Europe (ESAC data 1997–2002): trends, regional differences and seasonal fluctuations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 16:115–123

Eskola J, Kilpi T, Palmu A, Herva E et al (2001) Efficacy of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against acute otitis media. N Engl J Med 344:403–409

European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (2009) http://www.rivm.nl/earss/. Accessed Feb 2009

Farrell DJ, Klugman KP, Pichichero M (2007) Increased antimicrobial resistance among nonvaccine serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the pediatric population after the introduction of 7-valent pneumococcal vaccine in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J 26:123–128

Ferech M, Coenen S (2006) European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC): outpatient penicillin use in Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother 58:408–412

Finkelstein JA, Stille CJ et al (2005) Watchful waiting for acute otitis media: are parents and physicians ready? Pediatrics 115:1466–1473

Fischer TF, Singer AJ, Gulla J et al (2005) Reaction toward a new treatment paradigm for acute otitis media. Pediatr Emerg Care 21:170–172

Froom J, Culpepper L, Green LA et al (2001) A cross-national study of acute otitis media: risk factors, severity, and treatment at initial visit. Report from the International Primary Care Network (IPCN) and the Ambulatory Sentinel Practice Network (ASPN). J Am Board Fam Pract 14:406–417

Gabriel ME, Aiuto L, Kohn N, Barone SR (2004) Management of febrile children in the conjugate pneumococcal vaccine era. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 43:75–82

German Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases (DGPI) Guidelines (2009) Handbook 5th Edition

Gill PS, Mäkelä M, Vermeulen KM et al (1999) Changing doctor prescribing behaviour. Pharm World Sci 21:158–167

Gillespie R (1991) Manufacturing knowledge: a history of the Hawthorne experiments. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB, Hayem M, Sanders SL (2004) Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1:CD000219

Goossens H, Ferech M, Coenen S, Stephens P (2007) European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption Project Group. Comparison of outpatient systemic antibacterial use in 2004 in the United States and 27 European countries. Clin Infect Dis 44:1091–1095

Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R et al (2005) Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet 365:579–587

Greenberg D, Bilenko N, Liss Z (2003) The burden of acute otitis media on the patient and the family. Eur J Pediatr 162:576–581

Greenberg D, Hoffman S, Leibovitz E, Dagan R (2008) Acute otitis media in children: association with day care centers: antibacterial resistance, treatment, and prevention. Paediatr Drugs 10:75–83

Guevara S, Soley C, Arguedas A et al (2008) Seasonal distribution of otitis media pathogens among Costa Rican children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 27:12–16

Guillemot D, Varon E, Bernède C et al (2005) Reduction of antibiotic use in the community reduces the rate of colonization with penicillin G-nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis 41:930–938

Haggard M (2007) The relationship between evidence and guidelines. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 137(4 Suppl):S72–S77

Haggard M (2008) Otitis media: prospects for prevention. Vaccine 26S:G20–G24

Hall-Stoodley L, Hu FZ, Gieseke A et al (2006) Direct detection of bacterial biofilms on the middle-ear mucosa of children with chronic otitis media. JAMA 296:202–211

Harbarth S, Albrich W, Brun-Buisson C (2002) Outpatient antibiotic use and prevalence of antibiotic-resistant pneumococci in France and Germany: a sociocultural perspective. Emerg Infect Dis 8:1460–1467

Howard DH, McGowan JE Jr (2004) Initial and follow-up costs by treatment outcome for children with respiratory infections. Pediatrics 113:1352–1356

Hsu HE, Shutt KA, Moore MR et al (2009) Effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on pneumococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med 360:244–256

Huang SS, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K (2007) Parental knowledge about antibiotic use: results of a cluster-randomized, multicommunity intervention. Pediatrics 119:698–706

Johnson DL, McCormick DP, Baldwin CD (2008) Early middle ear effusion and language at age seven. J Commun Disord 41:20–32

Kennedy A, Gask L, Rogers A (2005) Training professionals to engage with and promote self-management. Health Educ Res 20:567–578

Kilpi T, Herva E, Kaijalainen T, Syrjänen R, Takala AK (2001) Bacteriology of acute otitis media in a cohort of Finnish children followed for the first two years of life. Pediatr Infect Dis J 20:654–662

Koopman L, Hoes AW, Glasziou PP et al (2008) Antibiotic therapy to prevent the development of asymptomatic middle ear effusion in children with acute otitis media: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 134:128–132

Kvaerner K, Liese J, Arguedas A et al. (2008) A European Survey highlights the clinical burden of children with otitis media. Presented at the 26th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPID), Graz, Austria

Liñares J, Ardanuy C, Pallares R, Fenoll A (2010) Changes in antimicrobial resistance, serotypes, and genotypes in Streptococcus pneumoniae over a thirty-year period. Clin Microbiol Infect 16(5):402–410

Lloyd A, Patel N, Scott DA et al (2008) Cost-effectiveness of heptavalent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (Prevenar) in Germany: considering a high-risk population and herd immunity effects. Eur J Health Econ 9:7–15

Lu CY, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB, Pearson SA (2008) Interventions designed to improve the quality and efficiency of medication use in managed care: a critical review of the literature—2001–2007. BMC Health Serv Res 8:75

Management of Acute Otitis Media. Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment: Number 15, June 2000. Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/epcsums/otitisum.htm. Accessed February 2009

Marchetti F, Ronfani L, Nibali SC et al (2005) Delayed prescription may reduce the use of antibiotics for acute otitis media: a prospective observational study in primary care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 159:679–684

McCormick DP, Chonmaitree T, Pittman C et al (2005) Nonsevere acute otitis media: a clinical trial comparing outcomes of watchful waiting versus immediate antibiotic treatment. Pediatrics 115:1455–1465

McNulty CA, Boyle P, Nichols T et al (2007) The public’s attitudes to and compliance with antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother 60(Suppl 1):i63–i68

Meropol SB, Glick HA, Asch DA (2008) Age inconsistency in the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for acute otitis media. Pediatrics 121:657–668

Moller AR (2009) A new epidemic: harm in health care. Nova Publsihers, Hauppage, www.novapublishers.com

Murphy TF, Bakaletz LO, Smeesters PR (2009) Microbial interactions in the respiratory tract. Pediatr Infect Dis J 28(10 Suppl):S121–S126

Murphy TF, Bakaletz LO, Kyd JM et al (2005) Vaccines for otitis media: proposals for overcoming obstacles to progress. Vaccine 23:2696–2702

NICE Short Clinical Guidelines Technical Team (2008) Respiratory tract infections—antibiotic prescribing. Prescribing of antibiotics for self-limiting respiratory tract infections in adults and children in primary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, London

Nederlands Huisarts Genootschap (2006). Otitis media acuta bij kinderen (M09) http://nhg.artsennet.nl/kenniscentrum/k_richtlijnen/k_nhgstandaarden/Samenvattingskaartje-NHGStandaard/M09_svk.htm

Ontario Guidelines Advisory Committee (2002) Summary of recommended guidelines. Otitis media: Antibiotic therapy. University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, MI (Available: http://www.gacguidelines.ca/index). Accessed March 2009

Paradise JL, Rockette HE, Colborn DK et al (1997) Otitis media in 2253 Pittsburgh area infants: prevalence and risk factors during the first two years of life. Pediatrics 99:318–333

Parsons S, Morrow S, Underwood M (2004) Did local enhancement of a national campaign to reduce high antibiotic prescribing affect public attitudes and prescribing rates? Eur J Gen Pract 10:18–23

Payer L (1988) Medicine & culture: varieties of treatment in the United States, England, West Germany, and France. Henry Holt, New York

Pelton SI (2007) Prospects for prevention of otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J 26(10 Suppl):S20–S22

Pichichero ME (2002) Diagnostic accuracy, tympanocentesis training performance, and antibiotic selection by pediatric residents in management of otitis media. Pediatrics 110:1064–1070

Pichichero ME, Casey JR (2005) Acute otitis media: making sense of recent guidelines on antimicrobial treatment. J Fam Pract 54:313

Plasschaert AI, Rovers MM, Schilder AG et al (2006) Trends in doctor consultations, antibiotic prescription, and specialist referrals for otitis media in children: 1995–2003. Pediatrics 117:1879–1886

Prevenar Prescribing information. Available: http://www.prevenar.co.uk/prescribinginfo.aspx. Accessed March 2009

Prymula R, Peeters P, Chrobak V (2006) Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides conjugated to protein D for prevention of acute otitis media caused by both Streptococcus pneumoniae and non-typable Haemophilus influenzae: a randomised double-blind efficacy study. Lancet 367:740–748

Quach C, Collet JP, LeLorier J (2004) Acute otitis media in children: a retrospective analysis of physician prescribing patterns. Br J Clin Pharmacol 57:500–505

Rashidian A, Eccles MP, Russel I (2008) Falling on stony ground? A qualitative study of implementation of clinical guidelines’ prescribing recommendations in primary care. Health Policy 85:148–161

Reuveni H, Asher E, Greenberg D et al (2006) Adherence to therapeutic guidelines for acute otitis media in children younger than 2 years. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 70:267–273

Rosenfeld RM, Kay D (2003) Natural history of untreated otitis media. Laryngoscope 113:1645–1657

Rosman S, Le Vaillant M, Schellevis F et al (2008) Prescribing patterns for upper respiratory tract infections in general practice in France and in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health 18:312–316

Rovers MM, Glasziou P, Appelman CL et al (2006) Antibiotics for acute otitis media: a meta-analysis with individual patient data. Lancet 368:1429–1435

Schindler C, Krappweis J, Morgenstern I, Kirch W (2003) Prescriptions of systemic antibiotics for children in Germany aged between 0 and 6 years. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 12:113–120

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (2003) SIGN 66: Diagnosis and Management of Childhood Otitis Media in Primary Care Available at: www.sign.ac.uk. Accessed February 2009

Sommet A, Guillemot D (2004) Antibiotic use in the community: the French experience (Chapter 30). In: Gould IM, van der Meer JW (eds) Antibiotic policies theory and practice. Lavoisier, France, pp 583–592

Song JH, Jung SI, Ko KS et al (2004) High prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among clinical Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in Asia (an ANSORP study). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:2101–2107

Stephenson H, Haggard M, Zielhuis G et al (1993) Prevalence of tympanogram asymmetries and fluctuations in otitis media with effusion: implications for binaural hearing. Audiology 32:164–174

Taylor JA, Kwan-Gett TS, McMahon EM Jr (2005) Effectiveness of a parental educational intervention in reducing antibiotic use in children: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 24:489–493

Taylor S, Suaya J, Suppapanya N, Kyaw M, Hausdorff W (2010) Eleven year trend of otitis media among children aged <2 years in the united states, 1997–2007. 28th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Disease (ESPID). 6–7th May 2010. Abstract A-229-0018-01334

Thompson PL, Gilbert RE, Long PF et al (2009) Effect of antibiotics for otitis media on mastoiditis in children: a retrospective cohort study using the United Kingdom general practice research database. Pediatrics 123:424–430

Thompson PL, Spyridis N, Sharland M et al (2009) Changes in clinical indications for community antibiotic prescribing for children in the UK from 1996–2006: will the new NICE prescribing guidance on upper respiratory tract infections be ignored? Arch Dis Child 94:337–340

Turner D, Leibovitz E, Aran A, Piglansky L et al (2002) Acute otitis media in infants younger than two months of age: microbiology, clinical presentation and therapeutic approach. Pediatr Infect Dis J 21:669–674

van de Sande-Bruinsma N, Grundmann H, Verloo D et al (2008) Antimicrobial drug use and resistance in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis 14:1722–1730

Vergison A (2008) Microbiology of otitis media: a moving target. Vaccine 26(Suppl 7):G5–G10

Vernacchio L, Vezina RM, Mitchell AA (2006) Knowledge and practices relating to the 2004 acute otitis media clinical practice guideline: a survey of practicing physicians. Pediatr Infect Dis J 25:385–389

Watson RL, Dowell SF, Jayaraman M et al (1999) Antimicrobial use for pediatric upper respiratory infections: reported practice, actual practice, and parent beliefs. Pediatrics 104:1251–1257

WHO Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance (2001) World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Available at: http://d.scribd.com/docs/q7kl9v8l1c9psrm5do1.pdf. Accessed March 2009

Williamson I, Benge S, Mullee M, Little P (2006) Consultations for middle ear disease, antibiotic prescribing and risk factors for reattendance: a case-linked cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 56:170–175

Zhou F, Shefer A, Kong Y, Nuorti JP (2008) Trends in acute otitis media-related health care utilization by privately insured young children in the United States, 1997–2004. Pediatrics 121:253–260

Acknowledgments

This publication represents the author’s own interpretation of the literature in this field from a health policy standpoint. It does not necessarily express the views of GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals (Dr. Veronique Mouton), who have reviewed an earlier draft and sponsored literature research and writing assistance, for which I thank Dr. Rae Hobbs and Karen Palmer (Livewire Communications).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Synflorix is a trademark of the GlaxoSmithKline Group of Companies and Prevenar/Prevnar is a trademark of Wyeth Lederle (Pfizer group)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Haggard, M. Poor adherence to antibiotic prescribing guidelines in acute otitis media—obstacles, implications, and possible solutions. Eur J Pediatr 170, 323–332 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-010-1286-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-010-1286-4