Abstract

The incidence, aetiology and pathophysiology of pneumomediastinum (PM), an uncommon and potentially serious disease in neonates and children, were evaluated. A retrospective chart review of all patients diagnosed with PM who were hospitalised in the intensive care unit of the University Children’s Hospital Zürich, Switzerland, from 2000 to 2006, was preformed. We analysed the incidence, severity and causes of PM and investigated the possible differences between neonatal and non-neonatal cases. Seven children and nine neonates were identified with PM. All patients had a good outcome. Six cases of PM in the group of children older than 4 weeks were deemed to be caused by trauma, infection and sports, whereas one case was idiopathic. All nine neonatal cases presented with symptoms of respiratory distress. We were able to attribute four cases of neonatal PM to pulmonary infection, immature lungs and ventilatory support. Five neonatal cases remained unexplained after careful review of the hospital records. In conclusion, PM in children and neonates has a good prognosis. Mostly, it is associated with extrapulmonary air at other sites. It is diagnosed by chest X-ray alone. We identified mechanical events leading to the airway rupture in most children >4 weeks of life, whereas we were unable to identify a cause in half of the neonates studied (idiopathic PM).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pneumomediastinum (PM) is defined as a mediastinal air leak. The experimental works of Macklin and Macklin provided insights into its pathophysiology [4, 5]; alveolar rupture occurs because of a pressure gradient between the alveolus and the surrounding tissues. This gradient develops either through overinflation of the alveolus or a reduction of interstitial pressure. The air that subsequently leaks into the interstitial tissue diffuses toward the peribronchial and perivascular tissue, and then towards the mediastinum, the neck and into the subcutaneous tissue. However, due to pressure equalisation between the affected and adjacent alveoli in the lungs, the interalveolar walls remain intact and the lungs inflated.

The diagnosis of PM is confirmed by frontal chest roentgenogram, including the cervical region. Typical radiological signs of PM include the continuous diaphragm sign (interposition of air between the pericardium and the diaphragm, which becomes visible in the central mediastinal part) and linear bands of mediastinal air parallelling the left side of the heart and the descending aorta (pleura is shown as a fine opaque line) with extension superiorly along the great vessels into the neck. In infants, the “spinnaker sign” (an upwards and outwards deviation of thymic lobes) can be seen when the thymus is raised above the heart by pneumomediastinal air that elevates the thymus and separates it from the cardiac silhouette beneath [2].

Various causes of PM are found in the literature, such as airway obstruction (e.g. foreign body aspiration), iatrogenic (e.g. mechanical ventilation), infections (e.g. pneumonia), obstructive lung disease (e.g. asthma), toxic effects (e.g. smoking), trauma (e.g. chest trauma), Valsalva manoeuvres (e.g. vomiting) and the weakness of tissue (e.g. anorexia nervosa). In spontaneous PM, the underlying lung is healthy and the air leak is thought to be atraumatic [3]. In neonates, known predisposing factors are mixed lung diseases, such as pneumonia or meconium aspiration syndrome, with coexisting atelectasis and airway obstruction [1]. However, only scarce literature is found about neonates with PM.

In this study, we retrospectively analysed the incidence, severity and causalities of PM in neonates and children >4 weeks of life admitted to our intensive care unit, and we investigated the possible differences between the groups.

Material and methods

We retrospectively reviewed all records of children diagnosed with PM who were hospitalised in the interdisciplinary neonatal and paediatric intensive care unit of the University Children’s Hospital in Zürich, Switzerland, between January 2000 and September 2006. The patients were divided into two groups according to their age: neonates (under 4 weeks of age) and children (over 4 weeks of age). We were interested in the causes of PM as documented by the treating physicians, the types and results of radiologic investigations performed, any invasive interventions used to treat PM, the severity of the PM and the length of stay in the intensive care unit.

Results

About 1,200 children are admitted to our intensive care unit per year. The incidence of PM in our intensive care unit was 0.08% for children >4 weeks of age and 0.1% for neonates. In all patients, PM was diagnosed by chest X-ray and all had a positive outcome related to the PM. All five patients with pneumopericardium (PP) did not suffer from any complications (e.g. pericardial tamponade).

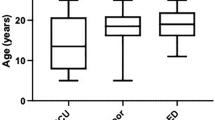

Seven children were >4 weeks of age (Table 1). Their mean age was 7.1 years (range 1.3–15.8 years). In addition to PM, two children of this group had subcutaneous emphysema (SE), two a pneumothorax (PT) and two a PP. Different causes were found for the air trapping. There were two traumatic aetiologies (rib fracture after a severe car accident, lesion in the hypopharynx after a fall). Two children were diagnosed with obstructive bronchitis and in one child, barotrauma occurred intraoperatively due to a clamped expiratory tube during mechanical ventilation (Fig. 1). One child had exercised vigorously three days before hospitalisation, which may have caused the PM. In one adolescent, PM occurred spontaneously. All children were hospitalised in the intensive care unit for one to seven days, depending on the severity of their underlying disease. Only two children required pleural drainage and intubation. All other children were treated for their underlying conditions and received oxygen therapy. Diagnostics for the PM other than chest X-rays were performed in four patients. All of these had received a thoracic CT scan. In one child, who also had a huge subcutaneous emphysema and dysphagia, the reason for the air trapping could only be found by means of a laryngotracheoscopy, which showed a traumatic lesion in the hypopharynx. The patient’s history revealed that she had fallen onto a piece of wood by her neck.

The group of children older than 4 weeks stayed in the intensive care unit for a mean of 3.2 days (range 1–7 days), depending on the severity of the PM and the underlying disease. Compared to the neonatal group, the length of stay in the intensive care unit was shorter. However, most neonates stayed in the intensive care unit longer, primarily because of comorbid conditions and not because of the PM.

We found nine neonates who were diagnosed with PM (Table 2); two premature and seven term infants, all of whom presented with signs of respiratory distress. Three neonates were also diagnosed with a PP, one with SE and five with a PT. Birth weight ranged from 2,150 g to 4,140 g (mean 3,340 g). Five children were born vaginally and four by caesarean section. All children were vigorous at birth and none required resuscitation with bag mask ventilation or surfactant. Before arriving in the intensive care unit, where the diagnosis of PM was confirmed by chest X-ray, two infants had received ventilatory support by CPAP and one of the premature infants had to be intubated for respiratory failure. During hospitalisation in the intensive care unit, two children deteriorated and required mechanical ventilation for three and four days, respectively, and two other children needed CPAP for a few hours. Only one child received pleural drainage. All children received oxygen therapy and specific therapy for their underlying disease. The age at admission to the intensive care unit ranged from a few hours to four days. One neonate was admitted to the intensive care unit due to convulsions and developed a PM on day six of life. The treating physicians felt that the PM may have been associated with a Valsalva manoeuvre, which occurred during the seizure. Other causes of PM were a pulmonary infection due to maternal infection and a possible barotrauma due to peak inspiratory pressure of 25 cm H2O in a mechanically ventilated premature neonate. Two newborns had PM related to CPAP and four neonates were diagnosed with spontaneous PM. Neonates stayed in the intensive care unit for 3–13 days (mean 5.6 days), depending on the severity of the underlying diseases.

Discussion

All children with PM had a good outcome without any complications due to air trapping.

In the group of children older than 4 weeks, only two children developed a respiratory insufficiency, leading to mechanical ventilation. In both of them, respiratory failure was related to their underlying condition (polytrauma with haematothorax and severe obstructive bronchitis, respectively). These were also the children who stayed longest in the intensive care unit. All other children were treated with oxygen only and stayed in the intensive care unit until they improved clinically and radiographically. Regarding radiologic diagnostics, four patients of the group of children >4 weeks of life had CT scans (three of them had been done in outside clinics from where the patients had been admitted to our intensive care unit). Retrospectively, the utility of the CT scans was put into question, as these scans did not change the patient management. The only patient in whom the CT scan changed management was the child with polytrauma. In this patient, other intrathoracic injuries needed to be ruled out.

In the group of neonates, it was much more difficult to find the aetiology of the PM, since all neonates had presented with respiratory disease, and radiologic investigations were partially performed only after the use of CPAP or tracheal intubation. Five of the nine neonates had a spontaneous PM without risk factors, such as mechanical respiratory support (bag mask ventilation after birth, CPAP, mechanical ventilation) or restrictive lung disease. Three of these five babies were delivered by caesarean section. In the remaining four newborns, possible mechanical incidents leading to the air leak could be revealed: mechanical ventilation with high inspiratory pressure, CPAP, pulmonary infection and convulsion. Further investigations are needed to find the aetiology of spontaneous PM in healthy, term neonates.

In conclusion, PM in children and neonates has a good prognosis. Mostly, it is associated with extrapulmonary air at other sites. It is diagnosed by chest X-ray alone. Whereas in older children mechanical events leading to the airway rupture can be revealed in most cases, about half of the neonates in our series suffered from PM without obvious reason.

Abbreviations

- CPAP:

-

Continuous positive airway pressure

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- PM:

-

Pneumomediastinum

- PP:

-

Pneumopericardium

- PT:

-

Pneumothorax

- Pip:

-

Positive inspiratory pressure

- SE:

-

Subcutanous emphysema

References

Carey B (1999) Neonatal air leaks: pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pulmonary interstitial emphysema, pneumopericardium. Neonatal Netw 18:81–84

Chalumeau M, Le Clainche L, Sayeg N, Sannier N, Michel J-L, Marianowski R, Jouvet P, Scheinmann P, de Blic J (2001) Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in children. Pediatr Pulmonol 31:67–75

Gesundheit B, Preminger A, Harito B, Babyn P, Maayan C, Mei-Zahav M (2002) Pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in an 18-month-old child. J Pediatr 141:116–120

Macklin CC (1939) Transport of air along sheaths of pulmonic blood vessels from alveoli to mediastinum: clinical implications. Arch Intern Med 64:913–926

Macklin MT, Macklin CC (1944) Malignant interstitial emphysema of the lungs and mediastinum as an important occult complication in many respiratory diseases and other conditions: an interpretation of the clinical literature in the light of laboratory experiments. Medicine 23:281–358

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hauri-Hohl, A., Baenziger, O. & Frey, B. Pneumomediastinum in the neonatal and paediatric intensive care unit. Eur J Pediatr 167, 415–418 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-007-0517-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-007-0517-9