Abstract

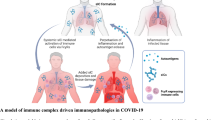

The current outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected people around the world. Typically, COVID-19 originates in the lung, but lately it can extend to other organs and lead to tissue injury and multiorgan failure in severe patients, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), kidney failure and sepsis or systemic inflammation. Given that COVID-19 has been detected in a range of other organs, the COVID-19-associated disease is an alert of aberrant activation of host immune response which drives un-controlled inflammation that affects multiple organs. Complement is a vital component of innate immunity where it forms the first line of defense against potentially harmful microbes, but its role in COVID-19 is still not clear. Notably, the abnormal activation and continuous deposits of complement components were identified in the pre-clinical samples from COVID-19 patients, which have been confirmed in animal models. Recent evidence has revealed that the administration of complement inhibitors leads to relieve inflammatory response in ARDS. Hence, we speculate that the targeting complement system could be a potential treatment option for organ damage in COVID-19 patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) occurred in December of 2019 and rapidly spread worldwide, resulting in a global pandemic of unprecedented magnitude. Great efforts are underway in the clinical and scientific communities to find effective ways to stop the spread of this novel virus [1,2,3,4].

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the family of Coronaviridae, seven of which are known to give rise to human disease [5]. During past years, two endemic outbreaks, SARS-CoV in 2003 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)-CoV in 2012 [6], occurred with significant consequences for public health. Compared to the antecedent epidemics of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, the transmission rate of SARS-CoV-2 is strikingly rapid since even asymptomatic individuals can transmit the virus. Patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection present a wide range of clinical presentations varies from asymptomatic to life-threatening that require ICU support [2, 3, 7, 8]. Patients who become critically ill have a risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), thrombotic complications, and multiorgan failure. This cataclysmic pattern of immune activation response, together with complement products found in clinical samples as documented here, are highly suggestive of aberrant activation of complement system in COVID-19.

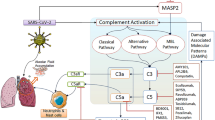

The complement system acts at the front line of host defense system to pathogens. It is part of the innate immune system and composed of nearly 30 more proteins [9]. The complement system can be activated in three traditional pathways (Fig. 1): the classical pathway (CP, initiated by antigen–antibody complex on pathogen surfaces), the lectin pathway (LP, binding of mannan-binding lectin (MBL) or ficolin to mannose containing carbohydrates on the surface of bacteria or viruses), and the alternative pathway (AP, spontaneously activated complement components binding to pathogen surface), characterized by proteolytic cascade events fueled by the C3 and C5 convertases. Eventually, the cleavage product C5b initiates the final step of complement activation, assembly of the membrane attack complex (MAC) C5b-9.

Although complement functions predominantly as innate immune response against bacterial or viral infections, unrestrained complement activation may promote detrimental inflammatory reaction and ultimately lead to tissue damage. For instance, the complement activation product, C5a, is a potent anaphylatoxin that involves in exacerbating inflammatory reactions and participates in multiorgan failure during sepsis [10]. In addition, there is an established crosstalk between the coagulation and fibrinolysis through thrombin- and plasmin-mediated complement activation. The C3a and C5 cleavage products, C5a and C5b, as well as mannose-associated serine protease 2 (MASP-2), influence many aspects of coagulation [11]. Recent evidence has revealed the complement system has well-described roles in influenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus infection. The most recent review article indicated the activation of complement and contact system may play a role in coronavirus pathogenesis by mice model study. However, further study is still needed to confirm the suspicions [12].

This review will focus on the recent literature and detail the significant emerging clinical and experimental findings of complement involvement in SARS-CoV-2, highlighting therapeutic strategies against complement.

Clinical evidence supporting complement engagement in COVID-19

Circulation pool (red blood cells/plasma/peripheral blood mononuclear cells/sera)

Despite a high infection rate of COVID-19, only a small proportion of patients require intensive care. No reliable clinical biomarkers are available yet to identify these patients early in their disease course. The circulation pool can provide convenient and accessible biological material for biomarker discovery and profiling. Thus, we start from the circulation pool to review complement activation in COVID-19 patients, including red blood cells (RBCs), plasma, peripheral blood cells (PBMCs), and sera, which might be useful for potential peripheral biomarker discovery (Table 1).

High-throughput transcriptomic and proteomic data are useful to draw pictures of host immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection and these data may yield potential critical diagnostic markers or therapeutic targets for monitoring COVID-19 patients. Two independent groups from Europe and China applied mass spectrometry to analyze the proteome of serum/plasma from COVID-19 patients [13, 14]. A general upregulation of complement system proteins, including the classical complement pathway (C1R, C1S, and C8A), the alternative pathway factor B, the complement modulators factors I and factor H, as well as MAC proteins such as C5, C6, and C8, were reflected in COVID-19 patients [13, 14]. Additionally, transcriptional changes in PBMCs from COVID-19 patients also showed that the up-regulated genes are enriched in “complement activation”, “humoral immune response mediated by circulating immunoglobulin”, and “B cell mediated immunity”, suggesting that activated complement components may play an important role in the disease process of COVID-19 [15].

In a recent study, Berzuini et al. described IgG bound to RBCs from most hospitalized patients with COVID-19 as observed in most of the positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT), with eluates reactive with RBCs from other patients with SARS-CoV-2 but not with reagent RBCs. They also observed C3d expression in 12% of the positive DATs, either in combination with IgG or in isolation [16, 17]. The classical pathway is primarily activated by antibodies bound to viral antigens. The formed immune complexes interact with C1q and initiate the classical pathway, which is associated with C3b deposition with viral envelop [18]. Similarly, another study reported that RBCs from patients with COVID-19 not only bound C3b/iC3b/C3dg and C4, but also bound viral spike protein, suggesting that viral infection may activate the classical pathway of the complement system [19].

A study from Saint-Louis hospital in France documented complement activity in plasma from 103 patients with COVID-19 [20]. In this study, the authors found that the levels of C3 and C4 were increased in some patients, and the level of circulating sC5b-9 was increased in 64% of the patients, highlighting the systemic complement activation during COVID-19 infection [20]. Additionally, the levels of sC5b-9 were significantly higher in patients than the healthy donors, and higher in the patients with severe disease than in the moderate disease group [20]. These findings were consistent with a single-center case series study from Italy [21].

Collectively, these data indicate that complement is activated in the circulation of COVID-19 patients, and it could cause further damage of microvasculature of different organs through systemic activated complement-mediated cytotoxicity.

Lung

The respiratory system is primarily involved in COVID-19, and a surge of patients developed ARDS. Clinical evidence suggests that activation of the complement system is critical in the pathogenesis of COVID-19-related lung injury (Table 2). A recent preprint study reported that the paraformaldehyde-fixed lung tissue from patients who died of COVID-19 revealed strong expression of complement components MBL, MASP-2, C4a, C3, and the terminal MAC C5b-9, suggesting LP complement hyper-activation occurred in the lungs of COVID-19 patients. In this article, the researchers demonstrated that viral N proteins from SARS-Cov, MERS-Cov, and SARS-Cov-2 could bind MBL and activate MASP-2, leading to the unrestrained activation of the complement cascade that participates in the pathogenesis of coronavirus infection [22, 23]. Simultaneously, a report from five severe COVID-19 infection cases documented significant deposits of terminal complement components C5b-9, C4d, and MBL-MASPs in the microvasculature in the lung [24]. This study also found a co-localization of COVID-19 spike glycoprotein with C4d and C5b-9 in the inter-alveolar septa [24]. As we all known, the main reason for admission and mortality of COVID-19 patients is respiratory failure. A recent study showed that the complement system markers of sC5b-9, C5a, C3bc, C3bBbP, and C4d were consistently increased in hospitalized COVID-19. And especially, MAC sC5b-9 was highly correlated with systemic inflammation and respiratory failure [25].

Further evidence comes from RNA-seq data from lung tissues of two patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. When comparing the transcriptome of patients to controls, the researchers found 36 canonical pathways significantly be induced in patients and 5 of the enriched pathways (14%) were annotated as complement pathways. To confirm if these are the SARS-Cov2-induced lung cell-intrinsic complement, the authors checked the transcriptome of primary human bronchial epithelial cells, A549 and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)-transduced A549 cells when infected with SARS-Cov-2 in vitro. Results showed that the complement pathways were among the most highly enriched of all pathways following SARS-Cov-2 infection, one of which was the most significantly induced pathway in A549-ACE2 cells [26]. These results suggest that respiratory epithelial cells are a primary source of complement within lung tissues.

Kidney

The main SARS-Cov-2 receptor, ACE2, is highly expressed in the apical brush borders of the proximal tubules and podocytes with less intensity, highlighting the relevance of kidney as a target of SARS-Cov-2 [27]. SARS-Cov-2 may directly bind with ACE2 expressed on kidney cells and lead to immune responses and the complement cascade locally [28]. Recent evidence has shown that a considerable incidence of renal abnormalities are associated with COVID-19, including proteinuria, hematuria and acute kidney injury [29]. The pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated renal injury is not well understood yet. A recent online report was done in kidney tissues from postmortems in China [30] (Table 2). The authors found C5b-9 depositions on tubules in all six cases along with low expression of C5b-9 on glomeruli and capillaries in two cases, indicating SARS-Cov-2 infection induced complement activation occurred in the kidney as well [30]. A preliminary autoptic examination of kidneys from seven COVID-19 patients in Italy was consistent with data regarding these Chinese patients [28]. These results indicate that the local complement activation and inflammation responses may contribute partially to kidney damage and dysfunction.

Skin

Cutaneous manifestations have been described in the setting of COVID-19 (Table 2). The role of systemic complement activation and microvascular thrombosis has been implicated in pathogenic mechanism of skin lesion. A report from Magro et al. documented that three patients with critical COVID-19 had purpuric skin rash with striking deposition of C5b-9 and C4d in both grossly involved and normally appearing skin, and colocalization of SARS-CoV-2-specific spike glycoprotein [24]. Two children with Kawasaki-like hyperinflammatory syndrome were reported as a novel SARS-CoV-2 induced phenotype in Italy [31] with other reports following. In that study, the authors described signs of mucocutaneous involvement, including conjunctivitis, fissured lips, skin rash, erythema, and edema of the hands and feet, developed in both patients [31]. Blood tests revealed elevated makers of inflammation, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and complement consumption [31]. It has been speculated that these manifestations might be a result of complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis.

The in vivo evidence of complement activation in animal models during coronavirus infection

Complement activation has been previously recognized as an important factor in the pathogenesis of SARS and MERS, both diseases mediated by coronaviruses that are similar to SARS-Cov-2. Thus, we will now review the scientific literature on animal models that were studied for the relationship between these coronavirus infections and complement (Table 3).

In wild-type mice, complement is activated after SARS-CoV MA15 (the mouse-adapted SARS-CoV) infection as demonstrated by elevated C3 activation products (C3 fragments C3a, C3b, iC3b, C3dg, and C3c) [32]. These mice exhibited pronounced lung pathology in parallel with humans, including inflammatory cells in the large airway and parenchyma, perivascular cuffing, thickening of the interstitial membrane and low levels of intra-alveolar edema [32]. In contrast, C3−/− mice showed a partial reduction of respiratory dysfunction, pathology, immune cell infiltration, and cytokine responses in the lung [32]. Additionally, factor B−/− or C4−/− mice also had less weight loss than WT mice [32]. These findings reveal that SARS-CoV infection activates complement systematically and enhances disease exacerbation.

In addition, in a mouse model of infection with the MERS-CoV, the deposition of C5b-9 and C5a both locally and systemically increased after viral infection [33]. Application of C5aR inhibitor attenuated pulmonary inflammation and led to decreased viral replication in infected lung [33].

Taken together, the available data provide evidence that complement is activated in coronavirus infection in experimental models and in patients. In the following section, we will discuss therapeutic anti-complement therapies.

The therapeutic perspective of complement inhibitors in SARS-CoV-2

As the list of COVID-19-associated pathophysiology linked to deregulated complement activation grows longer, it has become clear that complement inhibitors against C3 or C5 or activating pathways open new windows of therapeutic opportunity for treatment with severe COVID-19 cases. Because they could increase lung oxygenation, reduce lung inflammation, and the systemic complications of ARDS [34]. We provide a review of the complement inhibitors that are currently in clinical trials for COVID-19 (Fig. 1).

Proximal complement component C3 inhibitor

C3, the central hub of all complement pathways, represents a broad therapeutic target for potential anti-inflammatory therapy in COVID-19. Through inhibition of C3, subsequent production of C3a and C5a and formation of MAC can be prevented. AMY-101, as a highly selective and potent C3 inhibitor, was first successfully used in Italy for the treatment with a COVID-19 patient with severe pneumonia and systemic hyper-inflammation [35,36,37]. It is currently in Phase II clinical trials for the management of patients with ARDS caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04395456).

Anti-C5 monoclonal antibody (targeting the terminal pathway)

C5 inhibitors have been used in the clinical practice for almost 15 years, of which the most commonly used is eculizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody to C5 that prevents cleavage of C5 to C5a and C5b and blocks the formation of terminal complement complex C5b-9. To date, Eculizumab act as one of the complement system inhibitors, it is the only approved drug for FDA (Soliris; Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Cheshire, CT, USA). Eculizumab effectively treats paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria [37, 38], atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome [37, 39, 40], transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathies [36, 41], and autoimmune neuromuscular disorders [42]. Treatment with eculizumab has recently been reported in four severe COVID-19 related ARDS cases in Italy [43]. All patients successfully recovered after the treatment [43]. Based on this, two larger ongoing clinical trials are on the way in Europe (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04355494 and NCT04346797) and the United States (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04288713).

Ravulizumab is a long-acting version of eculizumab that exhibits high-affinity binding to C5 and inhibits C5a and C5b formation. A multicenter Phase 3, open-label randomized, controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of intravenously administered Ravulizumab compared with best supportive care in patients with COVID-19 severe pneumonia, acute lung injury or ARDS is being conducted in acute care hospital settings in the United States, United Kingdom, Spain, France, Germany, and Japan [44]. Yu et al. found that C5 monoclonal antibody prevents accumulation of C5b-9 on TF1PIGAnull cell but not upstream complement activation induced by the SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins [45]. Dense deposition of C3b could cause breakthrough from C5 inhibitors [46, 47]. Therefore, upstream factor H inhibitors might be more specific and effective at preventing the complement-mediated damage in COVID-19 patients [45].

Anti-C5a monoclonal antibody

The anti-C5a agents aim to selectively block the effect of C5a without affecting the formation of MAC [48, 49]. Thus, targeting C5a might be more effective than targeting C5. In China, two patients with severe COVID-19 benefited from treatment with anti-C5a monoclonal antibody therapy [23]. Multinational randomized controlled trials of the C5a monoclonal antibody, BDB-001 in China (2020L00003) and IFX-1 in Europe (NCT04333420), are already enrolling patients with severe and critical COVID-19 [23, 36, 37].

Anti-MASP-2 monoclonal antibody (Targeting the LP)

Evidence proved that MASP-2, the lectin pathway’s serine protease, bound with coronavirus N protein and was abnormally highly expressed in lung tissue of COVID-19 patients. Targeting the LP activation can be achieved by applying a human anti-MASP-2 monoclonal antibody [23, 24]. The therapeutic effect of anti-MASP-2 antibody Narsoplimab has been recognized in LP-activated thrombotic microangiopathies [36, 37, 50]. Interestingly, a recent study performed that Narsoplimab improved the clinical inflammation indicators in six COVID-19 patients at the first time, and non-reported adverse drug reactions [51]. However, anti-MASP-2 monoclonal antibody act as a new potential treatment strategy in COVID-19 is needed to confirm in the future.

Conclusion

Multiple organ involvement has been described in the setting of COVID-19. Although the mechanism is still not clear, emerging clinical and experimental evidence indicate that complement plays a key role in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and it has become a target for therapeutic intervention. However, the complement system is complicated and involved in a multiphasic role, where inhibiting part of or all three major pathways at the wrong time could potentially lead to harm. Hence, a better understanding of the role of complement in the setting of COVID-19 may help to optimize targeted therapies, including the ideal timing of such therapies in the disease course.

References

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W, China Novel Coronavirus I, Research T (2020) A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 382(8):727–733. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001017

Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, Schenck EJ, Chen R, Jabri A, Satlin MJ, Campion TR Jr, Nahid M, Ringel JB, Hoffman KL, Alshak MN, Li HA, Wehmeyer GT, Rajan M, Reshetnyak E, Hupert N, Horn EM, Martinez FJ, Gulick RM, Safford MM (2020) Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med 382(24):2372–2374. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2010419

Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, Cereda D, Coluccello A, Foti G, Fumagalli R, Iotti G, Latronico N, Lorini L, Merler S, Natalini G, Piatti A, Ranieri MV, Scandroglio AM, Storti E, Cecconi M, Pesenti A, Network C-LI (2020) Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA 323(16):1574–1581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394

Siordia JA Jr (2020) Epidemiology and clinical features of COVID-19: a review of current literature. J Clin Virol 127:104357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104357

Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of V (2020) The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol 5(4):536–544. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z

Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA (2012) Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 367(19):1814–1820. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1211721

Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C, Zimmer T, Thiel V, Janke C, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Drosten C, Vollmar P, Zwirglmaier K, Zange S, Wolfel R, Hoelscher M (2020) Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med 382(10):970–971. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2001468

Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, Tian F, Jin DY, Chen L, Wang M (2020) Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA 323(14):1406–1407. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2565

Sarma JV, Ward PA (2011) The complement system. Cell Tissue Res 343(1):227–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-010-1034-0

Huber-Lang M, Sarma VJ, Lu KT, McGuire SR, Padgaonkar VA, Guo RF, Younkin EM, Kunkel RG, Ding J, Erickson R, Curnutte JT, Ward PA (2001) Role of C5a in multiorgan failure during sepsis. J Immunol 166(2):1193–1199. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1193

Keragala CB, Draxler DF, McQuilten ZK, Medcalf RL (2018) Haemostasis and innate immunity—a complementary relationship: a review of the intricate relationship between coagulation and complement pathways. Br J Haematol 180(6):782–798. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.15062

Maglakelidze N, Manto KM, Craig TJ (2020) A review: does complement or the contact system have a role in protection or pathogenesis of COVID-19? Pulm Ther 6(2):169–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41030-020-00118-5

Shen B, Yi X, Sun Y, Bi X, Du J, Zhang C, Quan S, Zhang F, Sun R, Qian L, Ge W, Liu W, Liang S, Chen H, Zhang Y, Li J, Xu J, He Z, Chen B, Wang J, Yan H, Zheng Y, Wang D, Zhu J, Kong Z, Kang Z, Liang X, Ding X, Ruan G, Xiang N, Cai X, Gao H, Li L, Li S, Xiao Q, Lu T, Zhu Y, Liu H, Chen H, Guo T (2020) Proteomic and metabolomic characterization of COVID-19 patient sera. Cell 182(1):59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.032

Messner CB, Demichev V, Wendisch D, Michalick L, White M, Freiwald A, Textoris-Taube K, Vernardis SI, Egger AS, Kreidl M, Ludwig D, Kilian C, Agostini F, Zelezniak A, Thibeault C, Pfeiffer M, Hippenstiel S, Hocke A, von Kalle C, Campbell A, Hayward C, Porteous DJ, Marioni RE, Langenberg C, Lilley KS, Kuebler WM, Mulleder M, Drosten C, Suttorp N, Witzenrath M, Kurth F, Sander LE, Ralser M (2020) Ultra-high-throughput clinical proteomics reveals classifiers of COVID-19 infection. Cell Syst 11(1):11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2020.05.012

Xiong Y, Liu Y, Cao L, Wang D, Guo M, Jiang A, Guo D, Hu W, Yang J, Tang Z, Wu H, Lin Y, Zhang M, Zhang Q, Shi M, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Lan K, Chen Y (2020) Transcriptomic characteristics of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect 9(1):761–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1747363

Berzuini A, Bianco C, Paccapelo C, Bertolini F, Gregato G, Cattaneo A, Erba E, Bandera A, Gori A, Lamorte G, Manunta M, Porretti L, Revelli N, Truglio F, Grasselli G, Zanella A, Villa S, Valenti L, Prati D (2020) Red cell-bound antibodies and transfusion requirements in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Blood 136(6):766–768. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020006695

Hendrickson JE, Tormey CA (2020) COVID-19 and the Coombs test. Blood 136(6):655–656. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020007483

Stoermer KA, Morrison TE (2011) Complement and viral pathogenesis. Virology 411(2):362–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.045

Lam LM, Murphy SJ, Kuri-Cervantes L, Weisman AR, Ittner CAG, Reilly JP, Pampena MB, Betts MR, Wherry EJ, Song WC, Lambris JD, Cines DB, Meyer NJ, Mangalmurti NS (2020) Erythrocytes reveal complement activation in patients with COVID-19. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.20.20104398

Peffault de Latour R, Bergeron A, Lengline E, Dupont T, Marchal A, Galicier L, de Castro N, Bondeelle L, Darmon M, Dupin C, Dumas G, Leguen P, Madelaine I, Chevret S, Molina JM, Azoulay E, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Core G (2020) Complement C5 inhibition in patients with COVID-19—a promising target? Haematologica. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2020.260117

Cugno M, Meroni PL, Gualtierotti R, Griffini S, Grovetti E, Torri A, Panigada M, Aliberti S, Blasi F, Tedesco F, Peyvandi F (2020) Complement activation in patients with COVID-19: a novel therapeutic target. J Allergy Clin Immunol 146(1):215–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.006

Wilk CM (2020) Coronaviruses hijack the complement system. Nat Rev Immunol 20(6):350. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-020-0314-5

Gao T, Hu MD, Zhang XP, Li HZ (2020) Highly pathogenic coronavirus N protein aggravates lung injury by MASP-2-mediated complement over-activation. medRxiv:2020.2003.2029.20041962

Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, Nuovo G, Salvatore S, Harp J, Baxter-Stoltzfus A, Laurence J (2020) Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res 220:1–13

Holter JC, Pischke SE, de Boer E, Lind A, Jenum S, Holten AR, Tonby K, Barratt-Due A, Sokolova M, Schjalm C, Chaban V, Kolderup A, Tran T, Tollefsrud Gjlberg T, Skeie LG, Hesstvedt L, Ormsen V, Fevang B, Austad C, Muller KE, Fladeby C, Holberg-Petersen M, Halvorsen B, Muller F, Aukrust P, Dudman S, Ueland T, Andersen JT, Lund-Johansen F, Heggelund L, Dyrhol-Riise AM, Mollnes TE (2020) Systemic complement activation is associated with respiratory failure in COVID-19 hospitalized patien ts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117(40):25018–25025

Yan B, Freiwald T, Chauss D, Wang L, West E, Bibby J, Olson M, Kordasti S, Portilla D, Laurence A, Lionakis MS, Kemper C, Afzali B, Kazemian M (2020) SARS-CoV2 drives JAK1/2-dependent local and systemic complement hyper-activation. Res Sq. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-33390/v1

Su H, Yang M, Wan C, Yi LX, Tang F, Zhu HY, Yi F, Yang HC, Fogo AB, Nie X, Zhang C (2020) Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int 98(1):219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.003

Noris M, Benigni A, Remuzzi G (2020) The case of complement activation in COVID-19 multiorgan impact. Kidney Int 98(2):314–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.013

Martinez-Rojas MA, Vega-Vega O, Bobadilla NA (2020) Is the kidney a target of SARS-CoV-2? Am J Physiol Ren Physiol 318(6):F1454–F1462. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00160.2020

Diao B, Wang C, Wang R, Feng Z, Tan Y, Wang H, Wang C, Liu L, Liu Y, Liu Y, Wang G, Yuan Z, Ren L, Wu Y, Chen Y (2020) Human kidney is a target for novel severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. medRxiv:2020.2003.2004.20031120. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.04.20031120

Licciardi F, Pruccoli G, Denina M, Parodi E, Taglietto M, Rosati S, Montin D (2020) SARS-CoV-2-induced Kawasaki-like hyperinflammatory syndrome: a novel COVID phenotype in children. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-1711

Gralinski LE, Sheahan TP, Morrison TE, Menachery VD, Jensen K, Leist SR, Whitmore A, Heise MT, Baric RS (2018) Complement activation contributes to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus pathogenesis. MBio. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01753-18

Jiang Y, Zhao G, Song N, Li P, Chen Y, Guo Y, Li J, Du L, Jiang S, Guo R, Sun S, Zhou Y (2018) Blockade of the C5a–C5aR axis alleviates lung damage in hDPP4-transgenic mice infected with MERS-CoV. Emerg Microbes Infect 7(1):77. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41426-018-0063-8

Risitano AM, Mastellos DC, Huber-Lang M, Yancopoulou D, Garlanda C, Ciceri F, Lambris JD (2020) Complement as a target in COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol 20(6):343–344

Mastaglio S, Ruggeri A, Risitano AM, Angelillo P, Yancopoulou D, Mastellos DC, Huber-Lang M, Piemontese S, Assanelli A, Garlanda C, Lambris JD, Ciceri F (2020) The first case of COVID-19 treated with the complement C3 inhibitor AMY-101. Clin Immunol 215:108450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2020.108450

Jodele S, Kohl J (2020) Tackling COVID-19 infection through complement-targeted immunotherapy. Br J Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.15187

Polycarpou A, Howard M, Farrar CA, Greenlaw R, Fanelli G, Wallis R, Klavinskis LS, Sacks S (2020) Rationale for targeting complement in COVID-19. EMBO Mol Med 12(8):e12642. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.202012642

Hillmen P, Young NS, Schubert J, Brodsky RA, Socie G, Muus P, Roth A, Szer J, Elebute MO, Nakamura R, Browne P, Risitano AM, Hill A, Schrezenmeier H, Fu CL, Maciejewski J, Rollins SA, Mojcik CF, Rother RP, Luzzatto L (2006) The complement inhibitor eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med 355(12):1233–1243. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa061648

Fakhouri F, Hourmant M, Campistol JM, Cataland SR, Espinosa M, Gaber AO, Menne J, Minetti EE, Provot F, Rondeau E, Ruggenenti P, Weekers LE, Ogawa M, Bedrosian CL, Legendre CM (2016) Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in adult patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a single-arm, Open-Label Trial. Am J Kidney Dis 68(1):84–93. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.12.034

Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, Greenbaum LA, Babu S, Bedrosian C, Bingham C, Cohen DJ, Delmas Y, Douglas K, Eitner F, Feldkamp T, Fouque D, Furman RR, Gaber O, Herthelius M, Hourmant M, Karpman D, Lebranchu Y, Mariat C, Menne J, Moulin B, Nurnberger J, Ogawa M, Remuzzi G, Richard T, Sberro-Soussan R, Severino B, Sheerin NS, Trivelli A, Zimmerhackl LB, Goodship T, Loirat C (2013) Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med 368(23):2169–2181. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1208981

Jodele S, Dandoy CE, Lane A, Laskin BL, Teusink-Cross A, Myers KC, Wallace G, Nelson A, Bleesing J, Chima RS, Hirsch R, Ryan TD, Benoit S, Mizuno K, Warren M, Davies SM (2020) Complement blockade for TA-TMA: lessons learned from a large pediatric cohort treated with eculizumab. Blood 135(13):1049–1057. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019004218

Velez-Santamaria V, Nedkova V, Diez L, Homedes C, Alberti MA, Casasnovas C (2020) Eculizumab as a promising treatment in thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 13:1756286420932035. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756286420932035

Diurno F, Numis FG, Porta G, Cirillo F, Maddaluno S, Ragozzino A, De Negri P, Di Gennaro C, Pagano A, Allegorico E, Bressy L, Bosso G, Ferrara A, Serra C, Montisci A, D’Amico M, Schiano Lo Morello S, Di Costanzo G, Tucci AG, Marchetti P, Di Vincenzo U, Sorrentino I, Casciotta A, Fusco M, Buonerba C, Berretta M, Ceccarelli M, Nunnari G, Diessa Y, Cicala S, Facchini G (2020) Eculizumab treatment in patients with COVID-19: preliminary results from real life ASL Napoli 2 Nord experience. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 24(7):4040–4047. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202004_20875

Smith K, Pace A, Ortiz S, Kazani S, Rottinghaus S (2020) A Phase 3 open-label, randomized, controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of intravenously administered ravulizumab compared with best supportive care in patients with COVID-19 severe pneumonia, acute lung injury, or acute respiratory distress syndrome: a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 21(1):639. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04548-z

Yu J, Yuan X, Chen H, Chaturvedi S, Braunstein EM, Brodsky RA (2020) Direct activation of the alternative complement pathway by SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins is blocked by factor D inhibition. Blood 136(18):2080–2089. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020008248

Harder MJ, Kuhn N, Schrezenmeier H, Höchsmann B, von Zabern I, Weinstock C, Simmet T, Ricklin D, Lambris JD, Skerra A, Anliker M, Schmidt CQ (2017) Incomplete inhibition by eculizumab: mechanistic evidence for residual C5 activity during strong complement activation. Blood 129(8):970–980. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-08-732800

Brodsky RA, Peffault de Latour R, Rottinghaus ST, Röth A, Risitano AM, Weitz IC, Hillmen P, Maciejewski JP, Szer J, Lee JW, Kulasekararaj AG, Volles L, Damokosh AI, Ortiz S, Shafner L, Liu P, Hill A, Schrezenmeier H (2020) Characterization of breakthrough hemolysis events observed in the phase 3 randomized studies of ravulizumab versus eculizumab in adults with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Haematologica. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2019.236877

Carvelli J, Demaria O, Vely F, Batista L, Benmansour NC, Fares J, Carpentier S, Thibult ML, Morel A, Remark R, Andre P, Represa A, Piperoglou C, Explore C-IPHg, Explore C-MIg, Cordier PY, Le Dault E, Guervilly C, Simeone P, Gainnier M, Morel Y, Ebbo M, Schleinitz N, Vivier E (2020) Association of COVID-19 inflammation with activation of the C5a–C5aR1 axis. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2600-6

Mastellos DC, Ricklin D, Lambris JD (2019) Clinical promise of next-generation complement therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 18(9):707–729. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-019-0031-6

Elhadad S, Chapin J, Copertino D, Van Besien K, Ahamed J, Laurence J (2020) MASP2 levels are elevated in thrombotic microangiopathies: association with microvascular endothelial cell injury and suppression by anti-MASP2 antibody narsoplimab. Clin Exp Immunol 203:96–104

Rambaldi A, Gritti G, Mic MC, Frigeni M, Borleri G, Salvi A, Landi F, Pavoni C, Sonzogni A, Gianatti A, Binda F, Fagiuoli S, Di Marco F, Lorini L, Remuzzi G, Whitaker S, Demopulos G (2020) Endothelial injury and thrombotic microangiopathy in COVID-19: treatment with the lectin-pathway inhibitor narsoplimab. Immunobiology 225:152001

Funding

This work was supported by grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82000038).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors thank Dr. Jeanne Hendrickson (Department of Lab Medicine, Yale school of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA) for valuable guidance and thoughtful comments on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Edited by: Matthias J. Reddehase.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Q., Chen, Z. An update: the emerging evidence of complement involvement in COVID-19. Med Microbiol Immunol 210, 101–109 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00430-021-00704-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00430-021-00704-7