Abstract

A latent measure of white matter microstructure (g WM) provides a neural basis for information processing speed and intelligence in adults, but the temporal emergence of g WM during human development is unknown. We provide evidence that substantial variance in white matter microstructure is shared across a range of major tracts in the newborn brain. Based on diffusion MRI scans from 145 neonates [gestational age (GA) at birth range 23+2–41+5 weeks], the microstructural properties of eight major white matter tracts were calculated using probabilistic neighborhood tractography. Principal component analyses (PCAs) were carried out on the correlations between the eight tracts, separately for four tract-averaged water diffusion parameters: fractional anisotropy, and mean, radial and axial diffusivities. For all four parameters, PCAs revealed a single latent variable that explained around half of the variance across all eight tracts, and all tracts showed positive loadings. We considered the impact of early environment on general microstructural properties, by comparing term-born infants with preterm infants at term equivalent age. We found significant associations between GA at birth and the latent measure for each water diffusion measure; this effect was most apparent in projection and commissural fibers. These data show that a latent measure of white matter microstructure is present in very early life, well before myelination is widespread. Early exposure to extra-uterine life is associated with altered general properties of white matter microstructure, which could explain the high prevalence of cognitive impairment experienced by children born preterm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

White matter tracts connecting cortical networks are fundamental substrates of higher cognitive function in humans. ‘Disconnection’ of networks, which can be inferred from the microstructural properties of tracts, characterizes a number of diseases and contributes to functional impairment through reduced information transfer efficiency (Bartzokis et al. 2004; Penke et al. 2010; Ritchie et al. 2015b; Ball et al. 2015; Uddin et al. 2013; Liston et al. 2011). Tract connectivity has been widely investigated in vivo using diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) which is a non-invasive method that provides voxel-wise measures of water molecule diffusion. Since the molecular motion of water in the brain is influenced by biological factors including macromolecules, axonal diameter, membrane thickness and myelination, dMRI enables inference about underlying tract microstructure (LeBihan et al. 1986; Basser and Pierpaoli 1996).

In adulthood, microstructural properties of white matter are shared among major tracts (for example, an adult individual with high fractional anisotropy (FA) in one tract is likely to have high FA in all other tracts in the brain). This property allows for the derivation of a general factor, g FA, of white matter microstructure (Penke et al. 2010; Cox et al. 2016). The general factor explains almost half of variance in microstructure across major tracts, and latent variable statistical analyses show that g FA is predictive of information processing speed and intelligence (Penke et al. 2010, 2012; Ritchie et al. 2015b). The temporal emergence of g FA and other general factors of water diffusion biomarkers during human development is unknown and, therefore, its role in the ontogeny of human cognition has not been investigated.

Probabilistic neighbourhood tractography (PNT) is an automatic segmentation technique based on single seed point tractography, that can identify the same fasciculus-of-interest across a group of subjects by modelling how individual tracts compare with a predefined reference tract in terms of length and shape (Clayden et al. 2011). The method has been optimized for use with neonatal dMRI data, which enables tract-averaged measurements of mean ‹D›, axial (λ ax) and radial (λ rad) diffusivities, and FA, for the major white matter fasciculi during early brain development (corticospinal tracts, genu and splenium of corpus callosum, cingulum cingulate gyri, inferior longitudinal fasciculi) (Anblagan et al. 2015).

Early exposure to extra-uterine life by preterm birth is a leading cause of cognitive impairment in childhood and is strongly associated with a ‘disconnectivity’ phenotype that combines diffuse white matter injury and volume reduction of connected structures (Inder et al. 1999; Boardman et al. 2006; Volpe 2009; Ball et al. 2012). Altered development of thalamocortical networks in association with preterm birth is reported (Boardman et al. 2006; Ball et al. 2013, 2015; Toulmin et al. 2015), but structural and functional connectivity analyses in the newborn period and studies of adults born preterm suggests that network disruption is more widely distributed (Pandit et al. 2014; van den Heuvel et al. 2015; Smyser et al. 2016; Froudist-Walsh et al. 2015; Cole et al. 2015). This raises the hypothesis that disconnectivity in the context of preterm birth is a global rather than localized process.

Preterm birth is associated with an atypical social cognitive profile (Ritchie et al. 2015a). Early social cognition is also extremely tractable to measurement in infancy via measurement of gaze behaviour to social and non-social visual content. For example, visual attention is given to faces very soon after birth, with specific preference to the eye region, while at around 6–9 months a preference for looking at faces in multiple object arrays or animated scenes develops (Johnson et al. 1991; Farroni et al. 2002; Gliga et al. 2009). In addition, eye-movement recordings in response to social stimuli have been used to identify early behavioral trajectories associated with autism (Jones and Klin 2013), to link emergent social cognition with white matter microstructure in specific tracts (Elison et al. 2013), and to distinguish between the social cognitive profiles of infants born preterm and at term (Telford et al. 2016).

We tested the following hypotheses: first, a latent measure of general white matter microstructure (g WM) is present in the newborn; second, preterm birth is associated with global disconnectivity; and third, that g measured in the newborn period is associated with emergent social cognitive function in infancy.

Materials and methods

Participants

145 neonates (gestational age at birth range 23+2–41+5 weeks) were recruited from the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh between February 2013 and August 2015 to a longitudinal study of the effect of preterm birth on brain structure and long-term outcome. Infants had diffusion MRI (dMRI) at term equivalent age (mean GA 40+5 weeks, range 37+5–47+1) and 83 took part in eye-tracking assessment 6–12 months later (median age 7.9 months, IQR 6.8–8.8).

To study the effect of preterm birth on white matter microstructure the group was divided into those with GA at birth <35 weeks (n = 109), and healthy controls recruited from postnatal wards with GA 37–42 weeks (n = 36). Exclusion criteria included major congenital malformations, chromosomal abnormalities, congenital infection, overt parenchymal lesions (cystic periventricular leukomalacia, hemorrhagic parenchymal infarction) or post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilatation. Demographic information is shown in Table 1. Ethical approval was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service (South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee 02) and informed consent was obtained from the person with parental responsibility for all individual participants included in the study.

Of the preterm group: 7% had intra-uterine growth restriction (IUGR) defined as a birth weight under the third centile for gender and gestation and 31% had bronchopulmonary dysplasia defined as need for supplementary oxygen at 36 weeks’ PMA. PMA; postmenstrual age.

Image acquisition

A Siemens MAGNETOM Verio 3 T MRI clinical scanner (Siemens Healthcare Erlangen, Germany) and 12-channel phased-array head coil were used to acquire: T1-weighted MPRAGE (TR = 1650 ms, TE = 2.43 ms, inversion time = 160 ms, flip angle = 9°, voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3, and acquisition time = 7 min 49 s); T2-weighted SPACE (TR = 3800 ms, TE = 194 ms, flip angle = 120°, voxel size = 0.9 × 0.9 × 0.9 mm3, acquisition time = 4 min 32 s); dMRI using a protocol consisting of 11 T2- and 64 diffusion-weighted (b = 750 s/mm2) single-shot spin-echo echo planar imaging (EPI) volumes acquired with 2 mm isotropic voxels (TE = 106 ms and TR = 7300 ms). Infants were scanned without sedation in natural sleep using the feed-and-wrap technique. Physiological stability was monitored using procedures described by Merchant et al. (2009). Ear protection was provided for each infant (MiniMuffs, Natus Medical Inc., San Carlos, CA).

Image analysis

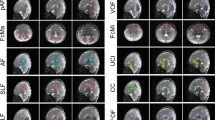

For all four imaging biomarkers (FA, MD, λ ax and λ rad), tract-averaged values were derived from eight major fasciculi segmented using probabilistic neighbourhood tractography (PNT) optimized for neonatal dMRI data (Bastin et al. 2010; Clayden et al. 2007; Anblagan et al. 2015). In summary after conversion from DICOM to NIfTI-1 format, the dMRI data were preprocessed using FSL tools (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) to extract the brain and eliminate bulk patient motion and eddy current-induced artifacts by registering the diffusion-weighted to the first T2-weighted EPI volume of each subject. Using DTIFIT, MD and FA volumes were generated for each subject. From the underlying white matter connectivity data, eight major white matter fasciculi thought to be involved in cognitive functioning were segmented: genu and splenium of corpus callosum, left and right cingulum cingulate gyrus (CCG), left and right corticospinal tracts (CST), and left and right inferior longitudinal fasciculi (ILF). As described in detail in the study by Anblagan et al. (2015), this involved using reference tracts created from a group of 20 term controls.

Cognitive testing

Infant social cognitive ability was assessed by tracking eye gaze in response to visual social stimuli using methods described by Telford et al. (2016). Infants were positioned on the care-giver’s lap 50–60 cm from a display monitor used to present social stimuli of three levels of complexity: a static face, a face in an array of non-social objects, and a pair of naturalistic scenes with and without social content. Proportional looking time to social content relative to the overall stimulus was recorded using a Tobii© ×60 eye-tracker, and Tobii Studio© (version 3.1.0) software was used for analysis. Because social preference scores that represent the distribution of fixation to social versus general image content are highly correlated across tasks, we combined social preference score from each task into a composite score per participant (Gillespie-Smith et al. 2016).

Statistical analysis

One principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted for each of the four water diffusion parameters (MD, FA, λ ax and λ rad) across the eight tracts, to quantify the proportion of shared variance between them (i.e. to determine whether a clear single-component solution was present, in line with previous reports in adults). That is, four separate data matrices (one for each DTI parameter) were separately analysed, each with dimensions n × m where n = 145 (number of subjects) and m = 8 (tract-averaged values for eight tracts). Thus, each PCA included data from all participants, and all available tracts were included; where tract data were missing (median 3.5% of tracts, IQR 3.5–13.25), the mean FA, MD, λ ax and λ rad of the group was used to impute values for the missing tract. Next, we examined the effect of preterm birth on differences in these four general water diffusion measures. Initially, we used a dichotomous group design, comparing differences between preterm infants’ and controls’ white matter microstructure (corrected for age at MRI scan) using Welch’s unpaired t tests. We then applied linear regression across the entire group to quantify the dose effect of birth term on each measure of microstructure, including PMA at MRI scan and sex as covariates in the model. To compare tract loadings (correlations between the manifest variable and extracted component score) for each tract between preterm infants and controls, we used Fisher’s test of correlation magnitude differences among independent groups (cocor.indep.groups in the cocor package in R) (Diedenhofen and Musch 2015). Finally, we examined associations between white matter microstructure and social cognitive performance using linear regression. The MRI and cognitive variables were corrected for differences in age at their respective data collection points prior to insertion into the model, where gender and group status (preterm/control) were covariates. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS v 21.0 (Chicago, IL), and R (https://www.r-project.org) version 3.2.2 (Fire Safety).

Results

General component of white matter microstructure

We ran separate PCAs for each measure of white matter microstructure on all eight tracts (Fig. 1). In each case there was a clear one component solution, denoted by its large eigenvalue, and the much lower and linearly decreasing eigenvalues of the remaining components. We extracted this first component, without rotation, which explained 49% (FA), 54% (MD), 59% (λ rad), and 36% (λ ax) of the variance (all loadings range between 0.409 and 0.870; Fig. 2; Table 2). Thus, there is a clear tendency for white matter microstructural properties found in one part of the newborn brain to be common across all white matter tracts, and the extracted water diffusion parameter values for each participant, therefore, reflect the level of white matter microstructure common across all tracts in that brain.

The effect of preterm birth on the general measure of white matter microstructure

There were significant differences in g for each of the four white matter water diffusion parameters between preterm and control groups: g FA (t = −4.1367, p = 8.139e−05); g MD (t = 5.2773, p = 1.062e−06); gλ rad (t = 5.4887, p = 4.322e−07); gλ ax (t = 4.2527, p = 5.529e−05), Fig. 3.

After adjustment for age at scan and sex we found significant associations between gestational age (GA) at birth and general measures of: FA (g FA), β 0.305 (p < 0.001); MD (g MD), β −0.351 (p < 0.001), λ rad (gλ rad) β −0.363 (p < 0.001); and λ ax (gλ ax) β −0.300 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). In summary, those infants born preterm exhibited less ‘mature’ microstructure (less coherent water diffusion and a greater general magnitude of water molecular diffusion) across their white matter tracts than controls. Moreover, we found a dose-dependent effect of GA at birth across all general white matter indices, such that more premature birth was associated with generally less optimal white matter microstructure.

Associations between PMA birth and general measures of fractional anisotropy (g FA) mean diffusivity (g MD), radial diffusivity (gλ rad) and axial diffusivity (gλ ax). Regression lines and 95% CIs (shaded) are shown for linear regression models between PMA at birth and white matter microstructure, corrected for age at scan and sex

In view of variations in newborn network connectivity (van den Heuvel et al. 2015), we considered whether individual tract loading of FA might differ between preterm and term groups. In exploratory analyses we found that loadings appeared qualitatively higher in callosal and corticospinal tracts for preterm versus control infants, but there was little evidence for group difference in tract loading in association fibers (Fig. 5). Formal tests of these differences using Fisher’s Z broadly confirmed this pattern for genu (z = 2.0593, p = 0.0395) and left CST (z = 2.3185, p value = 0.0204), though differences were not significant in the splenium (z = 1.6072, p value = 0.1080) and right CST (z = 1.4674, p value = 0.1423). This pattern was also present for λ rad and MD, though statistical tests indicated only trend-level or weaker differences for λ rad (genu: z = 1.8146, p = 0.0696; splenium: z = 1.8551, p = 0.0636; left CST: z = 1.6845, p = 0.0921; and right CST z = 1.2033, p = 0.2289) with the differences in the same direction for MD being smaller and non-significant.

Social cognitive ability and measures of general white matter microstructure

There were no significant associations between any general water diffusion parameter and a sensitive measure of emergent social cognition derived from an eye-tracking task battery at 7 months (all β absolute ≤ 0.123, all p values ≥0.265), and nor were there any significant effects of group within the model (all β absolute ≤ 0.099, all p values ≥0.378; Table 3). There was no relationship between water diffusion parameters and emergent social cognition in the genu (all p values ≥0.15) or splenium (all p values ≥0.064) of the corpus callosum. Social preference scores for each task (proportional looking time at social versus general image content) are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Discussion

In the human newborn brain microstructural properties of major white matter tracts are highly correlated with one another, which allows for the extraction of a general measure for each of four common water diffusion MRI parameters. This result suggests that individual differences in white matter microstructure during development are to a substantial degree common among tracts, and not a phenomenon that primarily affects specific individual tracts. Furthermore, the nature of between tract correlations is altered by the environmental exposure of preterm birth. Since global white matter microstructure contributes to the neural foundation of higher cognitive function in later life (Deary et al. 2010), and the factor loadings show remarkable similarity to those reported in adulthood (Penke et al. 2010), the data suggest that the fundamental white matter architecture required to support cognition is established as a generalized process during gestation, and that this is vulnerable to the environmental stress of preterm birth.

Inter-tract correlations were of similar strength for FA, MD and λ ax but were weaker for λ rad (Table 1). In the newborn period, before myelination is widespread, FA in white matter increases in association with maturation of axonal membrane structure, and increases in axonal caliber and oligodendrocyte number. MD in white matter is high around the time of birth but decreases over the first few months of postnatal life as brain water content lowers and localized restriction of water increases due to increased cell density and other factors (Huppi et al. 1998; Neil et al. 1998; Wimberger et al. 1995; Nomura et al. 1994; Morriss et al. 1999). Our data suggest that these processes affect the major tracts similarly around term equivalent age. The observation that λ ax was highly correlated between tracts could reflect the fact that neuronal migration has largely been completed by 24 weeks’ gestation so the axonal skeleton of major tracts is established (Bystron et al. 2008). λ rad was relatively weakly correlated between tracts, which could be explained by variation in myelination, which is known to be tract-specific (Kinney et al. 1988).

Having established that microstructural properties of tracts are substantially shared in the newborn, we next considered whether this relationship is modified by the environmental stress of preterm birth. After controlling for age at scan and sex, we found that the latent general measures of each of the four water diffusion parameters differed between preterm and control groups (Fig. 3): g FA was lower and g MD higher in preterms compared with healthy infants born at term. These data are consistent with studies that have used voxel- and tractography-based approaches to study the effect of preterm birth on the developing brain (Pannek et al. 2014; Ball et al. 2010; Anblagan et al. 2015), but methodological factors have left uncertainty about the extent to which microstructural change is a local versus a generalized process. Here, we demonstrate that preterm birth is associated with generalized differences across a functionally relevant representation of network architecture. Within this, however, we also found that group differences were most marked in projection and callosal fibers, which had higher loadings than association fibers in preterm infants compared with controls. Since neonatal water diffusion parameters are biomarkers of later neurodevelopmental function after preterm birth (Counsell et al. 2008; van Kooij et al. 2012; Boardman et al. 2010), the data presented here suggest that general properties of white matter microstructure could underlie the high prevalence of impairment seen in children and adults born preterm.

We found no relationship between general properties of any of the four water diffusion parameters and measures of infant social cognition derived from eye-tracking. The cognitive measure was selected because it discriminates between typically developing children and those with atypical cognitive trajectories, including those born preterm, and has been validated for use in infancy (Young et al. 2009; Ozonoff et al. 2010; Chawarska et al. 2013; Jones and Klin 2013; Telford et al. 2016; Gillespie-Smith et al. 2016). There are plausible explanations for this. First, general white matter ‘integrity’ is most closely associated with information-processing speed in adulthood but it is less predictive of other aspects of cognition (Ritchie et al. 2015b). Second, although processing speed is considered to be a foundational competence for other cognitive abilities in adulthood this relation may not hold true in infancy (Salthouse 1996; Ritchie et al. 2015b). Thus, in the infant, social cognition may develop on an independent trajectory relative to general processing abilities or emerging intelligence (Adolphs 1999). Further study is required to determine whether g WM relates to other aspects of infant cognition, such as sustained attention and memory. Longitudinal study will be required to determine whether foundational general measures of neonatal white matter microstructure influence later cognitive functions that are more reliant on information transfer efficiency.

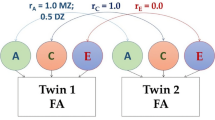

Brain structure, including dMRI measures in white matter, and intelligence are all highly heritable; twin studies suggest that up to 60% of inter-individual variation in dMRI measures are attributable to genetic factors (Thompson et al. 2001; Toga and Thompson 2005; Geng et al. 2012; Shen et al. 2014). Common genetic variants and epigenetic modifications modify the risk of white matter disease associated with preterm birth (Boardman et al. 2014; Krishnan et al. 2016; Dutt et al. 2011; Sparrow et al. 2016), but to our knowledge these associations have not been tested using a more functionally tractable set of brain biomarkers. We speculate that considering general measures of network architecture alongside tract-specific measures in imaging genetic studies will be useful for understanding the genetic and epigenetic determinants of connectivity in the newborn.

A limitation of this study is that we were unable to investigate the relationship between dMRI parameters of tracts that serve social cognition in adulthood, such as the arcuate fasciculus and fornix, and infant social cognition. Although PNT can segment these tracts from adult data (Clayden et al. 2007), we could not identify them reliably in the training set of neonatal data because of lower image resolution inherent to neonatal dMRI acquisitions.

A second limitation is that we did not examine other factors that may have contributed to white matter injury in the preterm group, such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia or punctate white matter lesions, because a much larger sample would have been required to adjust for these factors (Ball et al. 2010; Bassi et al. 2011). In addition, group sizes were unequal in the secondary analysis of the effect of preterm birth on component loadings; the preterm group was larger and thus could have contributed more strongly to the principal component score, influencing group comparisons. Consequently, although we found a statistically significant group effect for FA, MD and λ rad in the genu and CST, we cannot be certain that group differences are confined to these tracts alone. Though exploratory, these findings raise the possibility that preterm birth also subtly alters the correlational structure of infant white matter tracts with respect to specific classes of tract.

In summary, a latent general measure accounts for almost half of the variance of white matter tract microstructure in the newborn brain. Given that major white matter tracts constitute the neuroanatomical foundation of cognitive neural systems, our study indicates that a facsimile the network architecture for intelligence is established by birth, and that is it is vulnerable to early exposure to extra-uterine life.

References

Adolphs R (1999) Social cognition and the human brain. Trends Cognit Sci 3(12):469–479

Anblagan D, Bastin ME, Sparrow S, Piyasena C, Pataky R, Moore EJ, Serag A, Wilkinson AG, Clayden JD, Semple SI, Boardman JP (2015) Tract shape modeling detects changes associated with preterm birth and neuroprotective treatment effects. Neuroimage: Clin 8:51–58. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2015.03.021

Ball G, Counsell SJ, Anjari M, Merchant N, Arichi T, Doria V, Rutherford MA, Edwards AD, Rueckert D, Boardman JP (2010) An optimised tract-based spatial statistics protocol for neonates: applications to prematurity and chronic lung disease. Neuroimage 53(1):94–102

Ball G, Boardman JP, Rueckert D, Aljabar P, Arichi T, Merchant N, Gousias IS, Edwards AD, Counsell SJ (2012) The effect of preterm birth on thalamic and cortical development. Cereb Cortex 22(5):1016–1024

Ball G, Boardman JP, Aljabar P, Pandit A, Arichi T, Merchant N, Rueckert D, Edwards AD, Counsell SJ (2013) The influence of preterm birth on the developing thalamocortical connectome. Cortex 49(6):1711–1721. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2012.07.006

Ball G, Pazderova L, Chew A, Tusor N, Merchant N, Arichi T, Allsop JM, Cowan FM, Edwards AD, Counsell SJ (2015) Thalamocortical connectivity predicts cognition in children born preterm. Cereb Cortex (New York, NY: 1991). doi:10.1093/cercor/bhu331

Bartzokis G, Sultzer D, Lu PH, Nuechterlein KH, Mintz J, Cummings JL (2004) Heterogeneous age-related breakdown of white matter structural integrity: implications for cortical “disconnection” in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 25(7):843–851. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.09.005

Basser PJ, Pierpaoli C (1996) Microstructural and physiological features of tissues elucidated by quantitative-diffusion-tensor MRI. J Magn Reson B 111(3):209–219

Bassi L, Chew A, Merchant N, Ball G, Ramenghi L, Boardman J, Allsop JM, Doria V, Arichi T, Mosca F, Edwards AD, Cowan FM, Rutherford MA, Counsell SJ (2011) Diffusion tensor imaging in preterm infants with punctate white matter lesions. Pediatr Res 69(6):561–566

Bastin ME, Munoz MS, Ferguson KJ, Brown LJ, Wardlaw JM, MacLullich AM, Clayden JD (2010) Quantifying the effects of normal ageing on white matter structure using unsupervised tract shape modelling. Neuroimage 51(1):1–10

Boardman JP, Counsell SJ, Rueckert D, Kapellou O, Bhatia KK, Aljabar P, Hajnal J, Allsop JM, Rutherford MA, Edwards AD (2006) Abnormal deep grey matter development following preterm birth detected using deformation-based morphometry. Neuroimage 32(1):70–78

Boardman JP, Craven C, Valappil S, Counsell SJ, Dyet LE, Rueckert D, Aljabar P, Rutherford MA, Chew AT, Allsop JM, Cowan F, Edwards AD (2010) A common neonatal image phenotype predicts adverse neurodevelopmental outcome in children born preterm. Neuroimage 52(2):409–414

Boardman JP, Walley A, Ball G, Takousis P, Krishnan ML, Hughes-Carre L, Aljabar P, Serag A, King C, Merchant N, Srinivasan L, Froguel P, Hajnal J, Rueckert D, Counsell S, Edwards AD (2014) Common genetic variants and risk of brain injury after preterm birth. Pediatrics 133(6):e1655–e1663. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3011

Bystron I, Blakemore C, Rakic P (2008) Development of the human cerebral cortex: Boulder Committee revisited. Nat Rev Neurosci 9(2):110–122

Chawarska K, Macari S, Shic F (2013) Decreased spontaneous attention to social scenes in 6-month-old infants later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry 74(3):195–203. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.022

Clayden JD, Storkey AJ, Bastin ME (2007) A probabilistic model-based approach to consistent white matter tract segmentation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 26(11):1555–1561. doi:10.1109/tmi.2007.905826

Clayden JD, Maniega MS, Storkey AJ, King MD, Bastin ME, Clark CA (2011) TractoR: magnetic resonance imaging and tractography with R. J Stat Softw 44(8):1–18

Cole JH, Filippetti ML, Allin MP, Walshe M, Nam KW, Gutman BA, Murray RM, Rifkin L, Thompson PM, Nosarti C (2015) Subregional hippocampal morphology and psychiatric outcome in adolescents who were born very preterm and at term. PLoS One 10(6):e0130094. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130094

Counsell SJ, Edwards AD, Chew AT, Anjari M, Dyet LE, Srinivasan L, Boardman JP, Allsop JM, Hajnal JV, Rutherford MA, Cowan FM (2008) Specific relations between neurodevelopmental abilities and white matter microstructure in children born preterm. Brain 131(Pt 12):3201–3208. doi:10.1093/brain/awn268

Cox SR, Ritchie SJ, Tucker-Drob EM, Liewald DC, Hagenaars SP, Davies G, Wardlaw JM, Gale CR, Bastin ME, Deary IJ (2016) Ageing and brain white matter structure in 3,513 UK Biobank participants. Nat Commun 7:13629. doi:10.1038/ncomms13629

Deary IJ, Penke L, Johnson W (2010) The neuroscience of human intelligence differences. Nat Rev Neurosci 11(3):201–211. doi:10.1038/nrn2793

Diedenhofen B, Musch J (2015) cocor: A comprehensive solution for the statistical comparison of correlations. PLoS One 10(3):e0121945. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121945

Dutt A, Shaikh M, Ganguly T, Nosarti C, Walshe M, Arranz M, Rifkin L, McDonald C, Chaddock CA, McGuire P, Murray RM, Bramon E, Allin MP (2011) COMT gene polymorphism and corpus callosum morphometry in preterm born adults. Neuroimage 54(1):148–153

Elison JT, Paterson SJ, Wolff JJ, Reznick JS, Sasson NJ, Gu H, Botteron KN, Dager SR, Estes AM, Evans AC, Gerig G, Hazlett HC, Schultz RT, Styner M, Zwaigenbaum L, Piven J (2013) White matter microstructure and atypical visual orienting in 7-month-olds at risk for autism. Am J Psychiatry 170(8):899–908. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12091150

Farroni T, Csibra G, Simion F, Johnson MH (2002) Eye contact detection in humans from birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99(14):9602–9605. doi:10.1073/pnas.152159999

Froudist-Walsh S, Karolis V, Caldinelli C, Brittain PJ, Kroll J, Rodriguez-Toscano E, Tesse M, Colquhoun M, Howes O, Dell’Acqua F, Thiebaut de Schotten M, Murray RM, Williams SC, Nosarti C (2015) Very early brain damage leads to remodeling of the working memory system in adulthood: a combined fMRI/tractography study. J Neurosci 35(48):15787–15799. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.4769-14.2015

Geng X, Prom-Wormley EC, Perez J, Kubarych T, Styner M, Lin W, Neale MC, Gilmore JH (2012) White matter heritability using diffusion tensor imaging in neonatal brains. Twin Res Hum Genet 15(3):336–350

Gillespie-Smith K, Boardman JP, Murray IC, Norman JE, O’Hare A, Fletcher-Watson S (2016) Multiple measures of fixation on social content in infancy: evidence for a single social cognitive construct? Infancy 21(2):241–257. doi:10.1111/infa.12103

Gliga T, Elsabbagh M, Andravizou A, Johnson M (2009) Faces attract infants’ attention in complex displays. Infancy 14(5):550–562. doi:10.1080/15250000903144199

Huppi PS, Maier SE, Peled S, Zientara GP, Barnes PD, Jolesz FA, Volpe JJ (1998) Microstructural development of human newborn cerebral white matter assessed in vivo by diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatr Res 44(4):584–590

Inder TE, Huppi PS, Warfield S, Kikinis R, Zientara GP, Barnes PD, Jolesz F, Volpe JJ (1999) Periventricular white matter injury in the premature infant is followed by reduced cerebral cortical gray matter volume at term. Ann Neurol 46(5):755–760

Johnson MH, Dziurawiec S, Ellis H, Morton J (1991) Newborns’ preferential tracking of face-like stimuli and its subsequent decline. Cognition 40(1–2):1–19

Jones W, Klin A (2013) Attention to eyes is present but in decline in 2-6-month-old infants later diagnosed with autism. Nature 504(7480):427–431. doi:10.1038/nature12715

Kinney HC, Brody BA, Kloman AS, Gilles FH (1988) Sequence of central nervous system myelination in human infancy. II. Patterns of myelination in autopsied infants. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 47(3):217–234

Krishnan ML, Wang Z, Silver M, Boardman JP, Ball G, Counsell SJ, Walley AJ, Montana G, Edwards AD (2016) Possible relationship between common genetic variation and white matter development in a pilot study of preterm infants. Brain Behav. doi:10.1002/brb3.434

LeBihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, Grenier P, Cabanis E, Laval-Jeantet M (1986) MR imaging of intravoxel incoherent motions: application to diffusion and perfusion in neurologic disorders. Radiology 161:401–407

Liston C, Malter Cohen M, Teslovich T, Levenson D, Casey BJ (2011) Atypical prefrontal connectivity in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: pathway to disease or pathological end point? Biol Psychiatry 69(12):1168–1177. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.03.022

Merchant N, Groves A, Larkman DJ, Counsell SJ, Thomson MA, Doria V, Groppo M, Arichi T, Foreman S, Herlihy DJ, Hajnal JV, Srinivasan L, Foran A, Rutherford M, Edwards AD, Boardman JP (2009) A patient care system for early 3.0 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging of very low birth weight infants. Early Hum Dev 85(12):779–783. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.10.007

Morriss MC, Zimmerman RA, Bilaniuk LT, Hunter JV, Haselgrove JC (1999) Changes in brain water diffusion during childhood. Neuroradiology 41(12):929–934

Neil JJ, Shiran SI, McKinstry RC, Schefft GL, Snyder AZ, Almli CR, Akbudak E, Aronovitz JA, Miller JP, Lee BC, Conturo TE (1998) Normal brain in human newborns: apparent diffusion coefficient and diffusion anisotropy measured by using diffusion tensor MR imaging. Radiology 209(1):57–66

Nomura Y, Sakuma H, Takeda K, Tagami T, Okuda Y, Nakagawa T (1994) Diffusional anisotropy of the human brain assessed with diffusion-weighted MR: relation with normal brain development and aging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 15(2):231–238

Ozonoff S, Iosif AM, Baguio F, Cook IC, Hill MM, Hutman T, Rogers SJ, Rozga A, Sangha S, Sigman M, Steinfeld MB, Young GS (2010) A prospective study of the emergence of early behavioral signs of autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49(3):256–266

Pandit AS, Robinson E, Aljabar P, Ball G, Gousias IS, Wang Z, Hajnal JV, Rueckert D, Counsell SJ, Montana G, Edwards AD (2014) Whole-brain mapping of structural connectivity in infants reveals altered connection strength associated with growth and preterm birth. Cereb Cortex 24(9):2324–2333. doi:10.1093/cercor/bht086

Pannek K, Scheck SM, Colditz PB, Boyd RN, Rose SE (2014) Magnetic resonance diffusion tractography of the preterm infant brain: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 56(2):113–124. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12250

Penke L, Muñoz Maniega S, Murray C, Gow AJ, Hernández MC, Clayden JD, Starr JM, Wardlaw JM, Bastin ME, Deary IJ (2010) A general factor of brain white matter integrity predicts information processing speed in healthy older people. J Neurosci 30(22):7569–7574. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1553-10.2010

Penke L, Maniega SM, Bastin ME, Valdes Hernandez MC, Murray C, Royle NA, Starr JM, Wardlaw JM, Deary IJ (2012) Brain white matter tract integrity as a neural foundation for general intelligence. Mol Psychiatry 17(10):1026–1030. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.66

Ritchie K, Bora S, Woodward LJ (2015a) Social development of children born very preterm: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 57(10):899–918. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12783

Ritchie SJ, Bastin ME, Tucker-Drob EM, Maniega SM, Engelhardt LE, Cox SR, Royle NA, Gow AJ, Corley J, Pattie A, Taylor AM, Valdes Hernandez Mdel C, Starr JM, Wardlaw JM, Deary IJ (2015b) Coupled changes in brain white matter microstructure and fluid intelligence in later life. J Neurosci 35(22):8672–8682. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0862-15.2015

Salthouse TA (1996) The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychol Rev 103(3):403–428

Shen KK, Rose S, Fripp J, McMahon KL, de Zubicaray GI, Martin NG, Thompson PM, Wright MJ, Salvado O (2014) Investigating brain connectivity heritability in a twin study using diffusion imaging data. Neuroimage 100:628–641. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.041

Smyser CD, Dosenbach NU, Smyser TA, Snyder AZ, Rogers CE, Inder TE, Schlaggar BL, Neil JJ (2016) Prediction of brain maturity in infants using machine-learning algorithms. NeuroImage. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.05.029

Sparrow S, Manning JR, Cartier J, Anblagan D, Bastin ME, Piyasena C, Pataky R, Moore EJ, Semple SI, Wilkinson AG, Evans M, Drake AJ, Boardman JP (2016) Epigenomic profiling of preterm infants reveals DNA methylation differences at sites associated with neural function. Transl Psychiatry 6:e716. doi:10.1038/tp.2015.210

Telford EJ, Fletcher-Watson S, Gillespie-Smith K, Pataky R, Sparrow S, Murray IC, O’Hare A, Boardman JP (2016) Preterm birth is associated with atypical social orienting in infancy detected using eye tracking. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12546

Thompson PM, Cannon TD, Narr KL, van Erp T, Poutanen VP, Huttunen M, Lonnqvist J, Standertskjold-Nordenstam CG, Kaprio J, Khaledy M, Dail R, Zoumalan CI, Toga AW (2001) Genetic influences on brain structure. Nat Neurosci 4(12):1253–1258

Toga AW, Thompson PM (2005) Genetics of brain structure and intelligence. Annu Rev Neurosci 28:1–23

Toulmin H, Beckmann CF, O’Muircheartaigh J, Ball G, Nongena P, Makropoulos A, Ederies A, Counsell SJ, Kennea N, Arichi T, Tusor N, Rutherford MA, Azzopardi D, Gonzalez-Cinca N, Hajnal JV, Edwards AD (2015) Specialization and integration of functional thalamocortical connectivity in the human infant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112(20):6485–6490. doi:10.1073/pnas.1422638112

Uddin LQ, Supekar K, Menon V (2013) Reconceptualizing functional brain connectivity in autism from a developmental perspective. Front Hum Neurosci 7:458. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00458

van den Heuvel MP, Kersbergen KJ, de Reus MA, Keunen K, Kahn RS, Groenendaal F, de Vries LS, Benders MJ (2015) The neonatal connectome during preterm brain development. Cereb Cortex (New York, NY: 1991) 25(9):3000–3013. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhu095

van Kooij BJ, de Vries LS, Ball G, van Haastert I, Benders MJ, Groenendaal F, Counsell SJ (2012) Neonatal tract-based spatial statistics findings and outcome in preterm infants. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 33(1):188–194

Volpe JJ (2009) Brain injury in premature infants: a complex amalgam of destructive and developmental disturbances. Lancet Neurol 8(1):110–124

Wimberger DM, Roberts TP, Barkovich AJ, Prayer LM, Moseley ME, Kucharczyk J (1995) Identification of “premyelination” by diffusion-weighted MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr 19(1):28–33

Young GS, Merin N, Rogers SJ, Ozonoff S (2009) Gaze behavior and affect at 6 months: predicting clinical outcomes and language development in typically developing infants and infants at risk for autism. Dev Sci 12(5):798–814. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00833.x

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the families who consented to take part in the study and to the nursing and radiography staff at the Clinical Research Imaging Centre, University of Edinburgh (http://www.cric.ed.ac.uk) who participated in scanning the infants. The authors are grateful for the provision of stimuli from the University of Stirling (http://pics.psych.stir.ac.uk), and the British Autism Study of Infant Siblings Network (http://www.basisnetwork.org). We thank Thorsten Feiweier at Siemens Healthcare for collaborating with dMRI acquisitions (Works-in-Progress Package for Advanced EPI Diffusion Imaging). This work was supported by the Theirworld (http://www.theirworld.org) and was undertaken in the MRC Centre for Reproductive Health, which is funded by MRC Centre Grant (MRC G1002033). Dr. Simon Cox is supported by a Medical Research Council (MRC) Grant MR/M013111/1 and by The University of Edinburgh Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology (CCACE: http://www.ccace.ed.ac.uk), part of the cross-council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing Initiative for which funding from the MRC and Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) is gratefully acknowledged (MR/K026992/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Telford, E.J., Cox, S.R., Fletcher-Watson, S. et al. A latent measure explains substantial variance in white matter microstructure across the newborn human brain. Brain Struct Funct 222, 4023–4033 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-017-1455-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-017-1455-6