Abstract

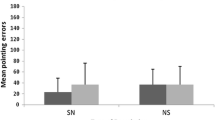

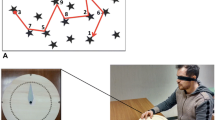

This study aimed to investigate the orientation dependence effect and the role of visuospatial abilities in mental representations derived from spatial descriptions. The analysis focused on how the orientation effect and the involvement of visuospatial abilities change when survey and route descriptions are used, and the initial and main orientation of an imaginary tour. In Experiment 1, 48 participants listened to survey or route descriptions in which information was mainly north-oriented (matching the initial heading and main direction of travel expressed in the description). In Experiment 2, 40 participants listened to route descriptions in which the initial orientation (north-oriented) was mismatched with the main direction of travel (east-oriented). Participants performed pointing task while facing north vs south (Exp. 1 and 2), and while facing east vs west (Exp. 2), as well as a map drawing task and several visuospatial measures. In both experiments, the results showed that pointing was easier while facing north than while facing south, and map drawings were arranged with a north-up orientation (with no difference between survey and route descriptions). In Experiment 2, pointing while facing east was easier than in the other pointing conditions. The results obtained with the visuospatial tasks showed that perspective-taking (PT) skill was the main predictor of the ability to imagine positions misaligned with the direction expressed in the descriptions (i.e. pointing while facing south in Experiment 1; pointing while facing north, south or west in Experiment 2). Overall, these findings indicate that mental representations derived from spatial descriptions are specifically oriented and their orientation is influenced by the main direction of travel and by the initial orientation. These mental representations, and the adoption of counter-aligned imaginary orientations, demand visuospatial skills and PT ability in particular.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In a preliminary analysis for Experiment 1, the Leg factor (Leg 1 vs. 2 vs. 3) was included in the ANOVA to check for any differences in pointing performance as a function of the leg involved; no significant effects were found, so this factor was not included in the final analyses.

Experiment 1. Two separate stepwise regression models were run on pointing while facing north and south for all visuospatial measures; both models were significant [F (2, 45) = 12.04 p ≤ .001 and F (3, 47) = 21.09 p ≤ .001, respectively], explaining 35 % and 59 % of the variance, respectively. In the first stepwise regression (pointing while facing north), the variables entered were MRT (β = −.40; t = −3.28 p ≤ .01) and sense of direction (β = −.36, t = −2.95, p ≤ .01); in the second stepwise regression (pointing while facing south), the variables entered were OPT (β = .43; t = 3.65, p ≤ .001), sense of direction (β = −.28, t = −2.68, p ≤ .01) and MRT (β = −.29, t = −2.63, p ≤ .01).

Experiment 2. The final 4 × 2 analysis of variance was based on the degrees of error without the segment going from the entrance to the ticket booth in Leg 4. When the same analysis was run including both the segments of Leg 4, the results showed the main effect of orientation F (3, 114) = 10.63, p ≤ .01 η 2 p = .28; post hoc comparisons confirmed that pointing while facing north (M = 32.63, SD 28.34) was easier than pointing while facing south (M = 41.68, SD 34.11) (as reported in the manuscript); on the other hand, pointing while facing east (M = 52.34, SD 17.45) coincided with a worse performance than pointing while facing west (M = 27.15, SD 23.20, p < .01) or north (p = .01) due to the greater error for the segment going from the entrance to the ticket booth.

Experiment 2. Two separate stepwise regression models were run on pointing while facing north and south for all visuospatial measures, and both models were significant [F (2, 39) = 12.53, p ≤ .001 and F (2, 39) = 14.11, p ≤ .001, respectively], explaining 40 and 43 % of the variance, respectively. In both models, the variables entered were the OPT [pointing while facing north: (β = .40), t = 2.89, p ≤ .01; pointing while facing south: (β = .42), t = 3.16, p ≤ .01], and the SIT [pointing while facing north: (β = −.37), t = −2.66, p = .01; pointing while facing south: (β = −.37), t = −2.72, p = .01]. The two stepwise regression models run on pointing while facing east and west generated significant results only for pointing while facing west, F (1, 39) = 13.05 p ≤ .01, explaining 27 % of the variance; the only variable entered in the model was the OPT [(β = .51), t = 3.61, p ≤ .001].

References

Allen, G. L., Kirasic, K. C., Dobson, S. H., Long, R. G., & Beck, S. (1996). Predicting environmental learning from spatial abilities: an indirect route. Intelligence, 22, 327–355. doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(96)90026-4.

Baldwin, C. L., & Reagan, I. (2009). Individual differences in route-learning strategy and associated working memory resources. Human Factors, 51, 368–377. doi:10.1177/0018720809338187.

Bosco, A., Filomena, S., Sardone, L., Scalisi, T. G., & Longoni, A. M. (1996). Spatial models derived from verbal descriptions of fictitious environments: the influence of study time and the individual differences in visuo-spatial ability. Psychologische Beiträge, 38, 451–464.

Brunye, T. T., & Taylor, H. A. (2008). Extended experience benefits spatial mental model development with route but not survey descriptions. Acta Psychologica, 127, 340–354. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.07.002.

Cornoldi, C., Rizzo, A., & Pra Baldi, A. (1991). Prove avanzate MT di comprensione della lettura [Advanced MT reading comprehension task]. Florence: Organizzazioni Speciali.

Corsi, P. M. (1972). Human memory and the medial temporal region of the brain [Doctoral dissertation]. Montreal: McGill University.

Fields, A. W., & Shelton, A. L. (2006). Individual skill differences and large-scale environmental learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 32, 506–515. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.32.3.506.

Frankenstein, J., Mohler, B. J., Bülthoff, H. H., & Meilinger, T. (2012). Is the map in our head oriented north? Psychological Science, 23, 120–125. doi:10.1177/0956797611429467.

Gagnon, S. A., Brunyé, T. T., Gardony, A., Noordzij, M. L., Mahoney, C. R., & Taylor, H. A. (2013). Stepping into a map: initial heading direction influences spatial memory flexibility. Cognitive Science,. doi:10.1111/cogs.12055.

Gyselinck, V., Cornoldi, C., Dubois, V., De Beni, R., & Ehrlich, M. F. (2002). Visuo-spatial memory and phonological loop in learning from multimedia. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 16, 665–685. doi:10.1002/acp.823.

Gyselinck, V., & Meneghetti, C. (2011). The role of spatial working memory in understanding verbal descriptions: a window onto the interaction between verbal and spatial processing. In A. Vandienrendonck & A. Szmalec (Eds.), Spatial Working Memory (pp. 159–180). Psychology Press, Portfolio.

Hegarty, M., Montello, D. R., Richardson, A. E., Ishikawa, T., & Lovelace, K. (2006). Spatial ability at different scales: individual differences in aptitude-test performance and spatial-layout learning. Intelligence, 34, 151–176. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2005.09.005.

Hegarty, M., & Waller, D. (2004). A dissociation between mental rotation and perspective-taking spatial abilities. Intelligence, 32, 175–191. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2003.12.001.

Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1983). Mental models: towards a cognitive science of language, inference and consciousness. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kozhevnikov, M., & Hegarty, M. (2001). A dissociation between object-manipulation spatial ability and spatial orientation ability. Memory and Cognition, 29, 745–756. doi:10.3758/BF03200477.

Lawton, C. A. (1996). Strategies for indoor wayfinding: the role of orientation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 16, 137–145. doi:10.1006/jevp.1996.0011.

Logie, R. H. (1995). Visuo-spatial working memory. UK: Lawrence Brlbaum Associates Ltd.

Meneghetti, C., Gyselinck, V., Pazzaglia, F., & Beni, De. (2009). Individual differences in spatial text processing: high spatial ability can compensate for spatial working memory interference. Learning and Individual Differences, 19, 577–589. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2009.07.007.

Meneghetti, C., De Beni, R., Gyselinck, V., & Pazzaglia, F. (2011a). Working memory involvement in spatial text processing: what advantages are gained from extended learning and visuo-spatial strategies? British Journal of Psychology, 102, 499–518. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.2010.02007.x.

Meneghetti, C., Pazzaglia, F., & De Beni, R. (2011b). Spatial mental representations derived from survey and route descriptions: when individuals prefer extrinsic frame of reference. Learning and Individual Differences, 21, 150–157. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2010.12.003.

Meneghetti, C., Ronconi, L., Pazzaglia, F., & De Beni, R. (2013). Spatial mental representation derived from spatial descriptions: the predicting and mediating role of spatial preferences, abilities and strategies. British Journal of Psychology. doi:10.1111/bjop.12038.

Montello, D. R., Waller, D., Hegarty, M., & Richardson, A. E. (2004). Spatial memory of real environments, virtual environments, and maps. In G. Allen (Ed.), Human spatial memory: remembering where (pp. 251–285). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Morrow, D. G., Stine-Morrow, E. A. L., Leirer, V. O., Andrassy, J. M., & Kahn, J. (1997). The role of reader age and focus of attention in creating situation models from narratives. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 52, 73–80. doi:10.1093/geronb/52B.2.P73.

Nori, R., & Giusberti, F. (2003). Cognitive styles: errors in directional judgments. Perception, 32, 307–320. doi:10.1068/p3380.

Pazzaglia, F. (2008). Text and picture integration in comprehending and memorizing spatial descriptions. In J. F. Rouet & R. K. Lowe (Eds.), Understanding multimedia documents (pp. 43–59). NYC, US: Springer.

Pazzaglia, F., & Cornoldi, C. (1999). The role of distinct components of visuo-spatial working memory in the processing of texts. Memory, 7, 19–41. doi:10.1080/741943715.

Pazzaglia, F., Cornoldi, C., & De Beni, R. (2000). Differenze individuali nella rappresentazione dello spazio: presentazione di un questionario autovalutativo [Individual differences in representation of space: presentation of a questionnaire]. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia, 3, 627–650. doi:10.1421/310.

Pazzaglia, F., & De Beni, R. (2001). Strategies of processing spatial information in survey and landmark-centred individuals. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 13, 493–508. doi:10.1080/09541440125778.

Pazzaglia, F., & De Beni, R. (2006). Are people with high and low mental rotation abilities differently susceptible to the alignment effect? Perception, 35, 369–383. doi:10.1068/p5465.

Pazzaglia, F., Gyselinck, V., Cornoldi, C., & De Beni, R. (2012). Individual differences in spatial text processing. In V. Gyselinck & F. Pazzaglia (Eds.), From mental imagery to spatial cognition and language: essays in honor of Michel Denis (pp. 127–161). Hove: Psychology Press.

Pazzaglia, F., & Meneghetti, C. (2012). Spatial text processing in relation to spatial abilities and spatial styles. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 24, 972–980. doi:10.1080/20445911.2012.725716.

Perrig, W., & Kintsch, W. (1985). Propositional and situational representations of text. Journal of Memory and Language, 24, 503–518. doi:10.1016/0749-596X(85)90042-7.

Presson, C. C., DeLange, N., & Hazelrigg, M. D. (1987). Orientation specificity in kinesthetic spatial learning: the role of multiple orientations. Memory & Cognition, 15, 225–229. doi:10.3758/BF03197720.

Presson, C. C., DeLange, N., & Hazelrigg, M. D. (1989). Orientation specificity in spatial memory: what makes a path different from a map of the path? Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 15, 887–897. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.15.5.887.

Presson, C. C., & Hazelrigg, M. D. (1984). Building spatial representations through primary and secondary learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 10, 716–722. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.10.4.716.

Richardson, A. E., Montello, D., & Hegarty, M. (1999). Spatial knowledge acquisition from maps and from navigation in real and virtual environments. Memory & Cognition, 27, 741–750. doi:10.3758/BF03211566.

Rinck, M., Hahnel, A., Bower, G. H., & Glowalla, U. (1997). The metrics of spatial situation models. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 32, 506–515. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.23.3.622.

Shelton, A. L., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2004). Neural correlates of individual differences in spatial learning strategies. Neuropsychology, 18, 442–449. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.18.3.442.

Shelton, A. L., & McNamara, T. P. (2001). Systems of spatial reference in human memory. Cognitive Psychology, 43, 274–310. doi:10.1006/cogp.2001.0758.

Shelton, A. L., & McNamara, T. P. (2004). Orientation and perspective dependence in route and survey learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 30, 158–170. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.30.1.158.

Sluzenski, J., Meneghetti, C., & McNamara, T. P. (2011). Spatial influence of environmental axes in a baseball field. Spatial Cognition & Computation, 11, 205–225. doi:10.1080/13875868.2010.542262.

Taylor, H. A., & Tversky, B. (1992). Spatial mental models derived from survey and route descriptions. Journal of Memory and Language, 31, 261–292. doi:10.1016/0749-596X(92)90014-O.

Vandenberg, S. G., & Kuse, A. R. (1978). Mental rotation, a group test of three-dimensional spatial visualization. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 47, 599–604. doi:10.2466/pms.1978.47.2.599.

Wechsler, D. (1981). Wechsler adult intelligence scale (rev. ed.). New York: Psychological Corporation.

Wildbur, D. J., & Wilson, P. N. (2008). Influences on the first-perspective alignment effect from text route descriptions. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61, 763–783. doi:10.1080/17470210701303224.

Wilson, P. N., Tlauka, M., & Wildbur, D. (1999). Orientation specificity occurs in both small- and large-scale imagined routes presented as verbal descriptions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 25, 664–679. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.25.3.664.

Wilson, P. N., & Wildbur, D. J. (2004). First-perspective alignment effects in a computer-simulated environment. British Journal of Psychology, 95, 197–217. doi:10.1348/000712604773952421.

Wolbers, T., & Hegarty, M. (2010). What determines our navigational abilities? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14, 138–146. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2010.01.001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meneghetti, C., Pazzaglia, F. & De Beni, R. Mental representations derived from spatial descriptions: the influence of orientation specificity and visuospatial abilities. Psychological Research 79, 289–307 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-014-0560-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-014-0560-x