Abstract

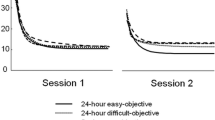

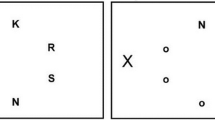

The anticipative learning model for acquiring action-effect relations states that the acquisition of action-effect relations depends on processes that are part of action planning, in particular the anticipation of possible effects. Experiment 1 shows that response planning is indeed crucial for the learning of response effects. In this experiment distractors (tones) were presented either during response preparation or in the time interval between response execution and the presentation of a response effect. Response-effect learning was impaired when the distractors were presented during response preparation. The finding is consistent with the assumption that the distractors impaired the anticipation of potential effects and therefore reduced effect learning. In Experiment 2 all responses had two effects. Participants were instructed to produce one of the effects. Under this condition, response-effect learning was only found for the instructed effect, not for the non-instructed effect. The two experiments thus support the view that response-effect learning is selective and depends on the anticipation of potential effects during response planning. The results are discussed in terms of a model that explains both the learning of response-effect relations and the use of these effects for action control within the same theoretical framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adams, J. A. (1971). A closed-loop theory of motor learning. Journal of Motor Behavior, 3, 111–149.

Cohen, A., Ivry, R. I., & Keele, S. W. (1990). Attention and structure in sequence learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 16, 17–30.

Coren, S. (1986). An efferent component in the visual perception of direction and extent. Psychological Review, 93, 391–410.

Elsner, B., & Hommel, B. (2001). Effect anticipation and action control. Journal of Experimental-Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27 229–240.

Eriksen, B. A., & Eriksen, C. W. (1974). Effects of noise letters on the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Perception & Psychophysics, 16, 143–149.

Frith, C.-D., Blakemore, S. J., & Wolpert, D. M. (2000). Explaining the symptoms of schizophrenia: Abnormalities in the awareness of action. Brain Research Reviews, 31, 357–363.

Haggard, P., Aschersleben, G., Gehrke, J., & Prinz, W. (2002). Action, binding, and awareness. In W. Prinz & B. Hommel (Eds.), Common Mechanisms in Perception and Action. Attention and Performance XIX. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Herbart, J. F. (1825). Psychologie als Wissenschaft neu gegründet auf Erfahrung, Metaphysik und Mathematik. Königsberg, Germany: August Wilhelm Unzer.

Hommel, B. (1993). Inverting the Simon effect by intention. Psychological Research, 55, 270–279.

Hommel, B. (1996). The cognitive representation of action: Automatic integration of perceived action effects. Psychological Research, 59, 176–186.

Hommel, B., Müsseler, J., Aschersleben, G., & Prinz, W. (2001). The theory of event coding (TEC): A framework for perception and action planning. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24, 849–937.

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology. New York: Holt.

Jordan, M. I. (1996). Computational aspects of motor control and motor learning. In H. Heuer & S. W. Keele (Eds.). Handbook of perception and action, Vol. 2: Motor skills (pp. 71–120). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Kunde, W. (2001). Response-effect compatibility in manual choice reaction tasks. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27, 387–394.

Kunde, W., Hoffmann, J., & Zellmann, P. (2002). The impact of anticipated action effects on action planning. Acta Psychologica, 109, 137–155.

Lotze, R. H. (1852). Medizinische Psychologie oder die Physiologie der Seele. Leipzig, Germany: Weidmann’sche Buchhandlung.

Münsterberg, H. (1888). Die Willenshandlung. Ein Beitrag zur physiologischen Psychologie [The intended act. A contribution to physiological psychology]. Freiburg, Germany: Mohr.

O’Regan, J. K., & Noe, A. (2001). A sensorimotor account of vision and visual consciousness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24, 939–1031.

Piaget, J. (1953). The origin of intelligence in children. New York: Routledge.

Prinz, W. (1992). Why don’t we perceive our brain states? European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 4, 1–20.

Prinz, W. (1997). Perception and action planning. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 9, 129–154.

Prinz, W., Meinecke, C., & Hielscher, M. (1987). Effect of stimulus degradation on category search. Acta Psychologica, 64, 187–206.

Schmidt, R. A. (1975). A schema theory of discrete motor skill learning. Psychological Review, 82, 225–260.

Shanks, D. R. (1995). Is human learning rational? Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Experimental Psychology, 48A, 257–279.

Wolff, P. (1986). Saccadic exploration and perceptual-motor learning. Acta Psychologica, 63, 263–280.

Wolff, P. (1999). Space perception and intended action. In G. Aschersleben, T. Bachmann, & J. Müsseler (Eds.). Cognitive contributions to the perception of spatial and temporal events. Advances in psychology, 129 (pp. 43–63). Amsterdam, Netherlands: North-Holland/Elsevier Science.

Wolpert, D. M., & Ghahrmani, Z. (2000). Computational principles of movement neuroscience. Nature: Neuroscience, 3, 1212–1217.

Wolpert, D. M., Miall, R. C., & Kawato, M. (1998). Internal models in the cerebellum. Trends in Cognitive Science, 2, 338–347.

Ziessler, M., & Nattkemper, D. (2001). Learning of event sequences is based on response-effect learning: Further evidence from a serial reaction task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 27, 595–613.

Ziessler, M., & Nattkemper, D. (2002). Effect anticipation in action planning. In W. Prinz & B. Hommel (Eds.), Common Mechanisms in Perception and Action. Attention and Performance XIX. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

The experiments were supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to Peter A. Frensch within the Research Group “Bindung: Funktionale Architektur, neuronale Korrelate und Ontogenese (FOR 448). We thank Britta Bruland for her assistance in performing the experiments and Wilfried Kunde and Jochen Müsseler for their very helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ziessler, M., Nattkemper, D. & Frensch, P.A. The role of anticipation and intention in the learning of effects of self-performed actions. Psychological Research 68, 163–175 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-003-0153-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-003-0153-6