Abstract

Aim

Anastomotic leakage (AL) is one of the most dreaded complications in colorectal surgery. In 2013, the International Classification of Diseases code K91.83 for AL was introduced in Germany, allowing nationwide analysis of AL rates and associated parameters. The aim of this population-based study was to investigate the current incidence, risk factors, mortality, clinical management, and associated costs of AL in colorectal surgery.

Methods

A data query was performed based on diagnosis-related group data of all hospital cases of inpatients undergoing colon or sphincter-preserving rectal resections between 2013 and 2018 in Germany.

Results

A total number of 690,690 inpatient cases were included in this study. AL rates were 6.7% for colon resections and 9.2% for rectal resections in 2018. Regarding the treatment of AL, the application of endoluminal vacuum therapy increased during the studied period, while rates of relaparotomy, abdominal vacuum therapy, and terminal enterostomy remained stable. AL was associated with significantly increased in-house mortality (7.11% vs. 20.11% for colon resections and 3.52% vs. 11.33% for rectal resections in 2018) and higher socioeconomic costs (mean hospital reimbursement volume per case: 14,877€ (no AL) vs. 37,521€ (AL) for colon resections and 14,602€ (no AL) vs. 30,606€ (AL) for rectal resections in 2018).

Conclusions

During the studied time period, AL rates did not decrease, and associated mortality remained at a high level. Our study provides updated population-based data on the clinical and economic burden of AL in Germany. Focused research in the field of AL is still urgently necessary to develop targeted strategies to prevent AL, improve patient care, and decrease socioeconomic costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A common yet dreaded postoperative complication in colorectal surgery is anastomotic leakage (AL), which is associated with longer hospitalization, a higher rate of reoperation, and higher overall morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. AL not only leads to a high clinical burden for the patients affected but causes significantly higher costs for hospitals and national health care systems [3]. Thus, research in the field of AL has increased over recent years with a number of records in the PubMed database for “anastomotic leakage” of 423 in the year 2010 and 1097 in 2020. Preoperative, tumor-associated, intraoperative, and other risk factors for AL have been identified so far [4, 5]. Research in the field thus focuses on identifying biomarkers for AL as well as finding optimal surgical techniques, biomaterials, and targeted drugs to reduce the risk of AL after gastrointestinal surgery; however, no treatment option except for diverting enterostomy exists so far to reliably prevent AL [6]. AL rates after lower gastrointestinal surgery are reported in the literature to occur in 1–19% of operations; however, reported leakage rates vary largely across studies [4, 7,8,9].

In 2013, the ICD (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) code K91.83 for postoperative gastrointestinal AL has been introduced to the German diagnosis-related group (DRG) system. DRG statistics data from all inpatients in German acute care hospitals are collected by the German Federal Statistical Office (DESTATIS). Microdata of the DRG statistics can be retrieved by researchers through the Research Data Centers associated with DESTATIS. These prerequisites make it possible to perform a retrospective population-based study analyzing AL rates and the resulting clinical and economic burden.

The aim of this study was to delineate current trends of AL rates in colorectal surgery in Germany by examining all inpatient cases from 2013 to 2018 based on DRG data sets. Furthermore, outcomes of patient care were assessed by studying therapeutic modalities for the clinical management of AL, mortality, hospital length of stay, and socioeconomic costs.

Methods

Data query and inclusion criteria

A data query through the Federal Statistical Office (DESTATIS) was performed for all inpatients undergoing colon resections (OPS 5–455) and sphincter-preserving rectal resections (OPS 5–484) from 2013 to 2018 in German acute care hospitals. Parameters retrieved were patient age and sex, main diagnosis, secondary diagnoses, postoperative complications and postoperative AL, morbidity scores, in-house mortality, therapeutic management of AL, length of hospital stay, and hospital reimbursement volume (Table S1). The Strausberg Comorbidity Score and weighed Elixhauser Score were used for the comparison of general comorbidity between patients with and without AL [10,11,12]. The code for the data query was written in SAS programming language according to the DESTATIS requirements. Data were retrieved through remote-controlled data processing and provided as raw data by DESTATIS [13]. The detailed methods and underlying regulations for reporting of inpatient cases in German hospitals have been previously described in detail [14,15,16,17]. In summary, all acute care hospitals in Germany are required by law to document and report every inpatient case with all relevant procedures and diagnoses, mainly for financial hospital reimbursement. The data are monitored for correctness by the medical service of the health insurance funds and stored by DESTATIS. The following data items per in-house hospital case are included in the DESTATIS database and can be queried for research purposes: main diagnosis (ICD), secondary diagnoses (ICD), procedures (OPS), age, year of birth, reason and type of admission, reason and type of discharge including in-hospital death, length of hospital stay, specialist department, Case Mix, Case Mix hospital reimbursement volume in EURO, hospital location (federal state, district, municipality, postal code), and patient residence (federal state, district, municipality, postal code). No temporal information regarding the sequence of procedures or diagnosis within one hospital case and no patient follow-up data can be retrieved from the database. Raw data from data queries are provided as pooled data (number of cases for defined combinations of ICD and OPS codes). For secondary data analysis used in this study, no ethics committee statement is required [18]. For data protection purposes, case numbers ≤ 2 are blinded by DESTATIS and not available to the authors.

Statistics

GraphPad Prism Version 9.1.2 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA) was used for statistical testing and data visualization. Fisher’s exact test, chi-square test, chi-square test for trend, and odds ratio were calculated. T- and Wilcoxon-signed rank tests were performed within the query code. Continuous parameters and variables are presented as mean with single standard deviation. Data were analyzed descriptively for each year and presented either as absolute numbers or relative rates. This study was conducted and reported using the STROBE Statement checklist [19].

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 690,690 cases were registered by DESTATIS from 2013 to 2018 and included in this study, 513,951 cases with colon resections, and 176,739 with sphincter-preserving rectal resections. The total number of colon resections was 87,853 in 2013 and 85,760 in 2018 and sphincter-preserving rectal resections were performed 31,195 times in 2013 and 28,834 times in 2018, decreasing slightly over the years (Fig. 1A).

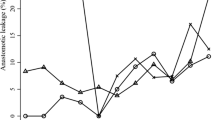

Development of surgery numbers from 2013 to 2018 for colon resection and sphincter-preserving rectal resection, anastomotic leakage rates, and risk factors. (A) The total number for colon resections was 87,853 in 2013 and 85,760 in 2018 and for sphincter-preserving rectal resections 31,195 in 2013 and 28,834 in 2018, decreasing slightly over the years. Data are absolute numbers per year. (B) The data show relative anastomotic leakage rates of 5.08% in 2013 and 6.74% in 2018 for colon resections and for sphincter-preserving rectal resections of 7.69% in 2013 and 9.15% in 2018. Data show relative rate per year. A linear trend towards higher leakage rates is shown. Chi-square test for trend, p ≤ 0.0001 = ****. (C, D) Anastomotic leakage rates with regard to secondary diagnosis, age range, and gender for colon resections (C) and sphincter-preserving rectal resections (D). Data are mean ± SD, dots are individual years. Bright blue and bright gray bar are mean leakage rates for all colon resections and all rectal resections. Two-sided Fisher’s exact test (secondary diagnosis, gender), chi-square test (age), p ≤ 0.0001 = ****. AL, anastomotic leakage

Anastomotic leakage rates

An increase in reported AL rates for both types of surgery was seen in the first 3 years after the introduction of the ICD-code K91.83 for postoperative AL. Reported relative AL rates for the total number of colon resections were 5.1% in 2013 and 6.7% in 2018 and for rectal resections 7.7% in 2013 and 9.2% in 2018 (Fig. 1B). The mean AL rate (from 2013 to 2018) was 6.2% for colon resections and 8.8% for rectal resections (Table 1).

Other postoperative complications

Postoperative abscess/surgical site infection rates following colon resections were 8.8% in 2013 and 7.7% in 2018 and for rectal resections 7.7% in 2013 and 6.6% in 2018. Wound dehiscence occurred with a rate of 6.5% in 2013 and 7.0% in 2018 for colon resections and with a rate of 5.6% in 2013 and 5.6% in 2018 for rectal resections. The rate of postoperative fistula formation was 5.6% in 2013 and 5.2% in 2018 for colon resections and 5.1% in 2013 and 4.6% in 2018 for rectal resections (Fig. S1).

Indication for surgery

Concerning the primary indication (main diagnosis) for colon and rectal resections, relevant differences in AL rates could be detected. For colon resections, patients with diverticulosis showed a significantly lower than average leakage rate (4.6%, OR 0.68). For patients with Crohn’s disease, the leakage rate was above average for colon resections (6.9%, OR 1.12). Patients with colorectal cancer showed a leakage rate of 6.3% which was not significantly different from the average leakage rate for colon resections of 6.2% (OR 1.02). For rectal resections, patients with diverticulosis showed a significantly lower than average leakage rate (6.6%, OR 0.69). For patients with Crohn’s disease (14.5%, OR 1.76) and patients with colorectal cancer (10.1%, OR 1.40), the leakage rate was higher than average for rectal resections (Table 1).

Risk factors for anastomotic leakage

Regarding the individual risk factors for AL, patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, cachexia, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease had significantly higher AL rates compared to cases without these secondary diagnoses (Fig. 1C, D). Leakage rates for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus were 6.9% (colon)/10.3% (rectum), obesity 7.7%/10.9%, cachexia 11.3%/13.7%, hypertension 6.5%/9.2%, and chronic kidney disease 8.0%/11.1% (Table 1). Additionally, a significant correlation between patient age and AL could be shown (p < 0.0001). Leakage rates were highest for patients between 61 and 80 years of age (Fig. 1C, D, Table 1). Regarding gender, male patients had significantly higher leakage rates than female patients for both colon resections (male: 7.4%, female 5.2%, p < 0.0001) and rectal resections (male: 11.3%, female: 6.4%, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1C, D). The general comorbidity was higher in patients with anastomotic leakage as evaluated with the Strausberg and weighed Elixhauser Comorbidity Scores (Table S2).

Management of anastomotic leakage

44.4% of patients with AL after colon resections and 32.9% of patients with AL after rectal resections underwent relaparotomy (2013). Relaparotomy rates for cases with AL only decreased for rectal resections over time (Fig. 2A). Abdominal vacuum therapy was performed in 16.6% of cases with AL after colon resections in 2013. For cases with AL after rectal resection, abdominal vacuum therapy was performed in 9.1% in 2013 (Fig. 2A). Regarding endorectal vacuum therapy, a significant increase over time could be detected. In 2013, endorectal vacuum therapy was performed in 3.5% of cases with colon resections and 17.8% of cases with rectal resections and postoperative AL. In 2018, endorectal vacuum therapy was performed in 7.1% of cases with colon resections and 30.0% of cases with rectal resections and AL (Fig. 2A). Terminal enterostomy was performed in 10.2% of cases after colon resections and AL and 6.4% of cases after rectal resections and AL in 2013. Rates for terminal enterostomy did not change significantly over time (Fig. 2A).

Management of anastomotic leakage and in-house mortality. (A) Procedures following anastomotic leakage after colon and rectal resections (relaparotomy, abdominal vacuum therapy, endorectal vacuum therapy, terminal enterostomy). Rates of procedures in cases with no anastomotic leakage (AL) are depicted for comparison. Data show relative rate per year. Chi-square test for trend. p < 0.05 = *, p ≤ 0.0001 = ****. Data for 2015 not available. (B, C) In-house mortality in % of cases undergoing colon resections (B) or rectal resections (C) without and with anastomotic leakage (AL). Data show relative rate per year. Chi-square test for trend. p < 0.05 = *, p ≤ 0.01 = **, p ≤ 0.0001 = ****. AL, anastomotic leakage

Mortality

The in-house mortality for patients undergoing colon resections without AL was 7.6% in 2013 and 7.1% in 2018. Mortality for patients with AL after colon resections was 22.2% in 2013 and 20.1% in 2018. A slight negative trend in mortality rates could be detected (Fig. 2B). The in-house mortality for patients undergoing rectal resections without AL was 4.6% in 2013 and 3.5% in 2018. Mortality for patients with AL after rectal resections was 11.8% in 2013 and 11.3% in 2018. Here, only a negative trend in mortality rates could be detected in patients with rectal resections without AL (Fig. 2C).

Length of hospital stay and hospital reimbursement

The occurrence of AL had a significant influence on the length of hospital stay in both colon and rectal resections. In 80% of cases with colon resections and AL, the length of hospital exceeded 20 days while in cases without AL, 28% of patients stayed in the hospital for more than 20 days, most likely due to other complications. In 80% of cases with rectal resections and AL, the length of hospital stay was longer than 20 days while in cases without AL, 25% of patients stayed in the hospital for more than 20 days (Fig. 3A, C).

Length of hospital stay and hospital reimbursement. (A, C) Distribution of cases to the length of hospital stay (≤ 5 days, 6–10 days, 11–20 days, ≥ 20 days). Data is depicted as percentage of total cases for colon resection ± anastomotic leakage (A) and rectal resection ± anastomotic leakage (C). A significant association between anastomotic leakage and length of hospital stay can be shown. Data are mean ± SD. Chi-square test. p ≤ 0.0001 = ****. (B, D) Mean hospital reimbursement sum per case for colon and rectal resections with and without anastomotic leakage. Data are mean reimbursement sum per year, t-test, p ≤ 0.0001 = ****. AL, anastomotic leakage

The mean hospital reimbursement sum for colon resections was 12,603€ without AL and 28,616€ with AL in 2013 and 14,876€ without versus 37,521€ with AL in 2018, showing an increase in the mean hospital reimbursement sum over time. Regarding rectal resections, the mean hospital reimbursement was 12,889€ without and 23,488€ with AL in 2013 and 14,602€ versus 30,606€ in 2018 (Fig. 3B, D; Table 2). To estimate the potential saving that could be achieved if AL could be prevented in all cases, we calculated a hypothetical sum from the mean hospital reimbursement rates of patients with and without AL (Table 2).

Discussion

With more than 690,000 inpatient cases undergoing colon resections and sphincter-preserving rectal resections, our study is currently the largest nation-wide population-based study to analyze AL rates after surgery of the lower gastrointestinal tract. Despite increasing research in the field of anastomotic healing and improvement of surgical techniques, our data show no decrease in leakage rates from 2013 to 2018 with a mean AL rate for colon resections of 6.2% and rectal resections of 8.8%.

Regarding individual risk factors for AL, known risk factors such as male gender, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and chronic kidney disease could be confirmed by our data [4, 7, 8]. Interestingly, cachexia showed the highest odds ratio for AL of 1.94 in cases with colon resections and 1.66 in cases with rectal resections (Table 1). When looking at the management of AL, there is a significant increase in endoscopic therapy in terms of endoluminal vacuum therapy over the years leading to a rate of 30% for AL after rectal resections in 2018; however, relaparotomy rates only slightly decreased in the studied period (Fig. 2A). Two potential factors could explain this phenomenon. Firstly, for an effective endoluminal vacuum therapy, the creation of a diverting enterostomy might be necessary thus requiring relaparotomy. Secondly, relaparotomy for peritoneal lavage might be required for patients with AL before or in combination with endorectal vacuum therapy thus not leading to a significant reduction in relaparotomy rates. Hence, our data suggests that although endoluminal vacuum therapy for AL after colorectal surgery is increasingly applied, it does not prevent revision surgery for lavage and creation of a protective enterostomy in all cases.

The AL rates that were coded increased over the observation period from 2013 to 2018, reaching a relatively stable level by 2015. The most probable cause is underreporting in the first years after the introduction of the ICD code K91.83 in 2013. The bias of under-reporting of AL in the following years is unlikely, as the hospitals would have deliberately waived a higher DRG-based reimbursement sum when treating for AL but not coding it in the case data. Over-reporting of diagnoses and procedures on the other hand is strictly controlled by the medical service of the health insurance funds in Germany but could still lead to a bias in our study. Other studies have described similar leakage rates but to our knowledge, no study had nearly as many cases or patients included in their data sets. Bonström et al. describe AL in 10% of the included 6948 patients undergoing low anterior resection in a population-based study from 2019 [20]. Gessler et al. describe AL rates of 7.0% for right hemicolectomy, 7.4% for left hemicolectomy, and 18.8% for rectal resection in a patient collective of 600 patients [2]. In a nationwide analysis from the USA, Midura et al. however show a much lower overall leakage rate of 3.8% [7]. The heterogeneity of assumed leakage rates has been reported several times recently [4, 21]. One confounder in most studies on AL rates is that postoperative diagnostic regimens are not standardized leading to under-diagnosis, especially of grade A leakage (according to the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer 2010) which is defined by not affecting the postoperative management [22]. However, with our study, we could show that despite increasing knowledge on the risk factors for AL, there was no trend towards decreasing leakage rates in the studied time period.

Regarding the economic burden of AL, only the DRG-based hospital reimbursement volume is accessible by our type of data query. A significant increase in the hospital reimbursement sum for cases with AL compared to cases without AL can be seen. We have calculated potential savings that could be achieved if no AL would occur (130,705,439 € for colon resections and 42,235,717 € for rectal resections in 2018, Table 2). However, the real costs of AL for the individual hospital cannot be derived from the DRG data. It has been described that the real cost of AL for the individual hospital is significantly higher and is not covered by the DRG-based reimbursement system. La Regina et al. could demonstrate in a study including 95 patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery, that the mean profit from the DRG-based reimbursement was 542€ per case without postoperative complications and the mean loss for cases with AL was 12,181€ per case for the hospital treating patients that developed AL [23]. In a study from England, Ashraf et al. could also demonstrate inadequate hospital reimbursement for cases with AL after low anterior rectum resections [24]. The slight increase in the overall hospital reimbursement sum is most likely due to the fact that the hospital reimbursement is calculated based on a base rate per inpatient hospital case, which increases steadily over time.

Ultimately, the question remains as to why AL rates have stagnated at such a high level. A Dutch study from 2022 investigated the impact of perioperative potentially modifiable risk factors on AL after colorectal surgery during a study period from January 2016 to December 2018 [25]. They identified modifiable risk factors such as low preoperative hemoglobin, surgical site contamination, hyperglycemia, and inadequate timing of perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis. Interestingly, most of these factors were already known to increase the risk of AL, but their prevention was still not applied before and during surgery. Although we could not draw these data from the DESTATIS dataset in our study, we suspect that the Dutch data are transferable to the situation in Germany. We therefore hypothesize that despite known preventive measures to reduce AL rates, adherence is still lacking in Germany, which could at least partly explain the stagnant AL rates in our study. Furthermore, we hypothesize that even if all standards to prevent AL are met, there is a residual risk for AL that has not yet been identified. Moreover, some patient-specific risk factors cannot be modified before surgery. To date, there are no established local or systemic pharmacological therapies to prevent anastomotic complications and improve the postoperative healing process in patients undergoing colorectal surgery. Therefore, with our study, we aim to raise awareness that AL is an unresolved problem in Germany, which represents an unchanged burden for patients as well as for health care providers and insurance companies.

Conclusions

This study presents a large population-based data set on AL rates following lower gastrointestinal surgery and gives a timely overview of the current data on AL rates and associated socioeconomic costs of AL after lower gastrointestinal surgery in Germany. The data show a great need for further research in the field of AL and for better adherence to perioperative standards to minimize known risks to efficiently reduce leakage rates and thus improve patient outcomes in the future. Furthermore, treatment for AL and care for affected patients must improve to reduce the high in-house mortality associated with AL.

Data availability

Due to the regulations of the Federal Statistical Office of Germany (DESTATIS), original data from the data query cannot be made available. However, the SAS code that was used to retrieve the data can be requested from the authors via email.

References

Lee SW, Gregory D, Cool CL (2020) Clinical and economic burden of colorectal and bariatric anastomotic leaks. Surg Endosc 34(10):4374–4381

Gessler B, Eriksson O, Angenete E (2017) Diagnosis, treatment, and consequences of anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 32(4):549–556

Ammann EM, Goldstein LJ, Nagle D, Wei D, Johnston SS (2019) A dual-perspective analysis of the hospital and payer-borne burdens of selected in-hospital surgical complications in low anterior resection for colorectal cancer. Hosp Pract (1995) 47(2):80–7

McDermott FD, Heeney A, Kelly ME, Steele RJ, Carlson GL, Winter DC (2015) Systematic review of preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative risk factors for colorectal anastomotic leaks. Br J Surg 102(5):462–479

Kruschewski M, Rieger H, Pohlen U, Hotz HG, Buhr HJ (2007) Risk factors for clinical anastomotic leakage and postoperative mortality in elective surgery for rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 22(8):919–927

Reischl S, Wilhelm D, Friess H, Neumann PA (2021) Innovative approaches for induction of gastrointestinal anastomotic healing: an update on experimental and clinical aspects. Langenbecks Arch Surg 406(4):971–80

Midura EF, Hanseman D, Davis BR, Atkinson SJ, Abbott DE, Shah SA et al (2015) Risk factors and consequences of anastomotic leak after colectomy: a national analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 58(3):333–338

Nikolian VC, Kamdar NS, Regenbogen SE, Morris AM, Byrn JC, Suwanabol PA et al (2017) Anastomotic leak after colorectal resection: a population-based study of risk factors and hospital variation. Surgery 161(6):1619–1627

Rullier E, Laurent C, Garrelon JL, Michel P, Saric J, Parneix M (1998) Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after resection of rectal cancer. Br J Surg 85(3):355–358

van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ (2009) A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care 47(6):626–633

Stausberg J, Hagn S (2015) New morbidity and comorbidity scores based on the structure of the ICD-10. PLoS ONE 10(12):e0143365

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM (1998) Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 36(1):8–27

Research data centres of the Federal Statistical Office and the statistical offices of the of the Federal States. Diagnosis-Related Group Statistics (DRG Statistics) 2013–2018, own calculations. https://doi.org/10.21242/23141.2013.00.00.1.1.0 to https://doi.org/10.21242/23141.2018.00.00.1.1.0

Stöß C, Nitsche U, Neumann PA, Kehl V, Wilhelm D, Busse R et al (2021) Acute appendicitis: trends in surgical treatment—a population-based study of over 800 000 patients. Dtsch Arztebl Int 118(14):244–249

Nimptsch U, Krautz C, Weber GF, Mansky T, Grützmann R (2016) Nationwide in-hospital mortality following pancreatic surgery in Germany is higher than anticipated. Ann Surg 264(6):1082–1090

Nimptsch U, Mansk T (2015) Deaths following cholecystectomy and herniotomy: an analysis of nationwide German hospital discharge data from 2009 to 2013. Dtsch Arztebl Int 112(31–32):535–543

Nimptsch U, Spoden M, Mansky T (2020) Definition of variables in hospital discharge data: pitfalls and proposed solutions. Gesundheitswesen (Bundesverband der Arzte des Offentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes (Germany)) 82(S 01):S29-s40.

Swart E, Gothe H, Geyer S, Jaunzeme J, Maier B, Grobe TG et al (2015) Good Practice of Secondary Data Analysis (GPS): guidelines and recommendations. Gesundheitswesen (Bundesverband der Arzte des Offentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes (Germany)) 77(2):120–6.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP (2007) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ 85(11):867–872

Boström P, Haapamäki MM, Rutegård J, Matthiessen P, Rutegård M (2019) Population-based cohort study of the impact on postoperative mortality of anastomotic leakage after anterior resection for rectal cancer. BJS Open 3(1):106–111

Kingham TP, Pachter HL (2009) Colonic anastomotic leak: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am Coll Surg 208(2):269–278

Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W, Heald RJ, Moran B, Ulrich A et al (2010) Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a proposal by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer. Surgery 147(3):339–351

La Regina D, Di Giuseppe M, Lucchelli M, Saporito A, Boni L, Efthymiou C et al (2019) Financial impact of anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 23(3):580–586

Ashraf SQ, Burns EM, Jani A, Altman S, Young JD, Cunningham C et al (2013) The economic impact of anastomotic leakage after anterior resections in English NHS hospitals: are we adequately remunerating them? Colorectal Dis 15(4):e190–e198

Huisman DE, Reudink M, van Rooijen SJ, Bootsma BT, van de Brug T, Stens J et al (2022) LekCheck: a prospective study to identify perioperative modifiable risk factors for anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 275(1):e189–e197

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was financially supported by the Stiftung Chirurgie, Technical University of Munich, covering the service fees required by the Federal Statistical Office of Germany for performing data queries.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: MCW, MB, CS, PAN; acquisition of data: MCW, MB; analysis and interpretation of data: MCW, MB, CS, SR, PAN; drafting of manuscript: MCW, MB, PAN; critical revision of manuscript: MCW, MB, CS, SR, DW, HF, PAN.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical statement

Data for this study was accessed remotely via the Research Data Centre of the Federal Statistical Office, Germany, by means of controlled data processing. For secondary data analysis used in this study, no ethics committee vote or support by the competent authority is required. For data protection purposes, case numbers ≤ 2 are blinded by the Federal Statistical Office and not available to the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weber, MC., Berlet, M., Stoess, C. et al. A nationwide population-based study on the clinical and economic burden of anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg 408, 55 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-023-02809-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-023-02809-4