Abstract

Purpose

Internal hernias (IH) are frequent complications after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB). Closure of the jejunal mesenteric and the Petersen defect reduces IH incidence in prospective and retrospective trials. This study investigates whether closing the jejunal mesenteric space alone by non-absorbable suture and splitting the omentum can be beneficial to prevent IH after LRYGB.

Methods

Observational cohort study of 785 patients undergoing linear LRYGB including omental split at a single institution, with 493 patients without jejunal mesenteric defect closure and 292 patients with closure by non-absorbable suture, and a minimal follow-up of 2 years. Patients were assessed for appearance and severity of IH. Additionally, open mesenteric gaps without herniated bowel as well as early obstructions due to kinking of the entero-enterostomy (EE) were explored.

Results

Through primary mesenteric defect closure, the rate of manifest jejunal mesenteric and Petersen IH could be reduced from 6.5 to 3.8%, but without reaching statistical significance. The most common location for an IH was the jejunal mesenteric space, where defect closure during primary surgery reduced the rate of IH from 5.3 to 2.4%. Higher weight loss seemed to increase the risk of developing an IH.

Conclusion

The closure of the jejunal mesenteric defect by non-absorbable suture may reduce the rate of IH at the jejunal mesenteric space after LRYGB. However, the beneficial effect in our collective is smaller than expected, particularly in patients with good weight loss. The Petersen IH rate remained low by consequent T-shape split of the omentum without suturing of the defect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Metabolic surgery is a safe and efficient treatment for morbid obesity in terms of weight loss and amelioration of related comorbidities [1,2,3,4,5]. The laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) is a standard procedure worldwide [6,7,8,9]. Due to the growing number of patients undergoing LRYGB, surgeons are faced with increasing numbers of postoperative complications such as internal hernias (IH) [10,11,12]. In prospective and retrospective studies, closure of mesenteric defects reduces IH incidence after LRYGB with an antecolic alimentary limb (AL) [13, 14]. But adverse effects associated with closure of mesenteric defects, such as bowel obstruction by kinking of the entero-enterostomy (EE) or mesenteric hematomas, are infrequently seen [15]. Closing mesenteric defects is widely accepted, but the applied technique (e.g., metal clips or non-absorbable sutures) is still subject for investigation [16,17,18]. In addition to the closure technique, there also is a question as to whether closure of the jejunal mesenteric space (space between the EE and the mesentery) alone is sufficient. A large retrospective series strongly supports the recommendation to close the jejunal mesenteric defect and the Petersen space (between the AL and the transverse mesocolon) [19]. Also, in a meta-analysis performed by Geubbels et al., the combination of jejunal mesenteric space and Petersen space closure seems to generate the lowest rates of IH in the long-term [10].

In the past, we observed a reduction of IH from 12.3 to 5.8% by changing from circular stapled gastroenterostomy (GE) (biliopancreatic limb [BPL] oriented to the right) to linear stapled GE (BPL oriented to the left). In the original version of the linear stapled LRYGB technique described by Hans Lönroth, the mesenteric defects were not closed, but the omentum was routinely split in the vertical direction to facilitate a tension free anastomosis between AL and the pouch [7]. As a consequence of the evidence provided by Aghajani et al. and Stenberg et al., in 2016, we started closing mesenteric defects as part of our antecolic linear LRYGB technique [13, 17, 20]. However, though the rate of Petersen hernias was low in our previously published results, the new closure technique could cause obstruction of the transverse colon or bleeding at the transverse mesocolon. The aforementioned authors stopped splitting the omentum routinely and/or performed an incision of the mesentery to allow the EE to drop below the level of the transverse colon to prevent a Petersen hernia; we only closed the jejunal mesenteric defect by a non-absorbable suture and split the omentum in a T-shape. The objective of this study is to analyze possible benefits of suture closure of the jejunal mesenteric defect and simultaneous omentum T-shape split without suture of the Petersen space. In comparison to a group of patients undergoing LRYGB without closure of any defects, we analyzed the appearance, localization, and severity of IH.

Materials and methods

This is an observational cohort study with prospectively collected data. Informed consent was obtained from all participants as a mandatory part of quality control in our hospital. The local ethics committee approved the study (EKNZ 2018/00356).

Patients and data

At our institution, we perform approximately 300 bariatric operations per year. All patients with morbid obesity are assessed by an interdisciplinary team (endocrinologist, psychiatrist, nutritionist, and bariatric surgeon) in accordance with national guidelines. Before 2011, criteria to perform metabolic surgery in Switzerland included a body mass index (BMI) > 40 kg/m2 or > 35 kg/m2 with the presence of at least one comorbidity and failed conservative treatment over 2 years. From 2011 to the present, a BMI > 35–50 kg/m2 and failed conservative treatment over 2 years or 1 year with a BMI > 50 kg/m2 became preconditions to qualify for surgery [21]. All data, including demographic information, weight loss as well as complications and comorbidities are, prospectively entered into our clinical database.

In the context of our study, only primary LRYGB procedures and cases, which passed the 2-year follow-up period were included for analysis; patients who did not attend two consecutive standard appointments in our outpatient clinic were considered lost to follow-up.

Surgical procedure

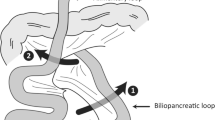

In 2009, we changed from the circular to the linear stapling LRYGB technique. Our technique has been described in detail previously [20]. In brief, the GE between the gastric pouch and the alimentary limb is created by two-thirds of the length of a 45-mm linear stapler magazine. The omentum is divided into a “T-shape” fashion (first widely separated parallel from the transverse colon and then split vertically), creating enough space for the antecolic AL to be placed without torsion and facilitating adhesions to potentially prevent bowel herniation. The 50-cm BPL was placed in the left side of the abdominal cavity, and the AL was orientated to the right. The creation of the EE was conducted using a 45-mm linear stapler side-to-side. A small window was created to allow the passage of the stapling device to divide the small intestine between the AL and the BPL close to the GE. When the jejunal mesenteric space was closed, we placed a non-absorbable barbed purse string-suture to close the vertex of the jejunal mesenteric space and closed the cranial part of the gap by running suture with the same thread.

Internal hernia assessment

Included in the analysis were patients who received surgery for abdominal pain and/or signs of intestinal obstruction with a clinically high suspicion of IH. IH was defined as herniation of bowel through the jejunal mesenteric or the Petersen space detected in laparoscopy or laparotomy. Appearance of obstruction or ischemia was recorded separately. Obstruction was described as any obvious dilatation of the intestine, while ischemia was defined as bluish change of intestine color or venous congestion. In cases of ischemia, the need for bowel resection was included in the evaluation. Next to IH, open mesenteric gaps without content as well as early obstructions due to kinking of the EE and 30 days of complications were assessed separately.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were summarized using mean and standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were summarized using counts and percentages. BMI change between study groups was compared by using an independent t-test. Time-to-event data were displayed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves with corresponding Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests. Numbers of active patients under surveillance were displayed as number at risk for different timepoints. Only the time-to-first event was considered due to very rare second events. Comparisons between study groups were reported showing hazard ratios (HR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p values. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 for Windows Version 8.4.1 [22].

Results

Patient characteristics

In the period from 2/2009 to 3/2018, 820 patients underwent primary laparoscopic linear LRYGB at our institution. Of the 820 patients, 785 completed 2 years follow-up (95.7%). Of those 785 patients, the first 493 patients did not receive a closure of the jejunal mesenteric defect (non-closure group) and the remaining 292 patients did receive closure of the primary jejunal mesenteric defect (closure group). There was no statistically significant difference in baseline demographic data between the two groups (Table 2). Since we started closing the jejunal mesenteric defect in 2016, the non-closure group had a significantly longer follow-up time compared to the closure group (5.8 ± 2.1 years vs. 2.9 ± 0.8 years [p = 0.0001]). There was no statistically significant difference in weight loss between the groups at all time points (Table 1; Fig. 1)

a Weight evolution curve showing weight in BMI, distinguishing patients with non-closure of the jejunal mesenteric defect from patients operated with closure of the jejunal mesenteric defect. Number of patients at risk (active patients) displayed on top. b BMI 1 and 2 years after primary LRYGB, distinguishing between the whole collective with no IH or no open mesenteric gap vs. all patients with IH or open mesenteric gap event. The boxes show the median and IQR. Single data points represent each individual patient, and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum range of values. P-values displayed from unpaired t-test. BMI body mass index, SD standard deviation, IH internal hernia. Gaps: open mesenteric gaps at the jejunal mesenteric space or the Petersen space

Early obstructions and complications of initial bariatric procedure

We observed 5 (1.0%) early obstructions in the non-closure group vs. two [0.7%] in the closed group (p ≥ 0.99). All early obstructions were seen within the first 2 weeks after surgery. Treatment consisted of bypassing the EE by side-side anastomosis between the end of the AL with the common limb (CL) and the end of the BPL with the CL in addition to the placement of a gastrostomy tube.

Internal hernias

In total, 67 patients presented typical symptoms of an IH and received diagnostic laparoscopy (51 [10.3%] in the non-closure vs. 16 patients [5.5%] in the closure group [p = 0.02]). The average time from primary to revisional surgery was longer in the non-closure group than in the closure group (2.8 ± 2.2 years vs. 1.3 ± 1.1 years [p = 0.009]). BMI at the time of revisional surgery showed no difference between the groups. In both collectives, revisional surgery could be carried out laparoscopically in most cases (80.4% vs. 93.8% [p = 0.27]) (Table 2).

The rate of overall manifest IH confirmed upon revisional laparoscopy could be reduced from 6.5 to 3.8% by primarily closing the jejunal mesenteric defect, but without reaching statistical significance (p = 0.14). The most common location for an IH was the jejunal mesenteric space, where defect closure during primary surgery could reduce the rate of IH from 5.3 to 2.4% (p = 0.06). The Petersen space hernia incidence was comparable with 2.2% in the non-closure vs. 1.4% in the closure group (p = 0.59). The only statistically significant difference that could be shown in absolute numbers was the reduction of an open jejunal mesenteric space without herniated bowel between the non-closure compared vs. the closure group (5.1% to 1.4% [p = 0.01]) (Table 2). In general, patients undergoing revisional surgery with suspicion of IH had lower BMI than patients without an event (28.1 ± 4.6 kg/m2 vs. 29.6 ± 4.5 kg/m2 [p = 0.02] after 1 year and 27.6 ± 4.1 kg/m2 vs. 29.3 ± 4.8 kg/m2 [p = 0.01] after 2 years, respectively). The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) at baseline in patients undergoing revisional surgery with suspicion of IH was 11.7% in the non-closure vs. 12.5% in the closure group. Alternatively, 17.4% of patients without an event in the non-closure group and 14.9% of patients without an event in the closure group were suffering from T2DM at baseline.

The IH and event-free survival figures demonstrate the appearance of IH or open mesenteric gaps over time. There was only a small benefit in overall manifest IH reduction (HR 0.90; CI = 0.46–1.75; p = 0.75) (Fig. 2a), manifest jejunal mesenteric hernias reduction (HR 0.74; CI = 0.34–1.60; p = 0.45) (Fig. 2b), and in hernias at the Petersen space (HR 0.85; CI = 0.28–2.56; p = 0.77) (Fig. 2c), for suture closure of the jejunal mesenteric defect. However, no IH occurred after 3 years in the closure group with 177 patients remaining at risk (Fig. 2)

a Kaplan-Meyer survival curve showing all IH cases (i.e., all cases with herniated bowel). b IH cases at the jejunal mesenteric space. c IH cases at the Petersen space, respectively. Number of patients at risk (active patients) displayed on top. HR, 95% CI and p-values displayed from Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, IH internal hernia

In all patients undergoing revisional surgery, both gaps were closed with a non-absorbable running suture. Two patients with IH were pregnant (35 and 33 weeks of pregnancy, respectively). The patient in the 35th week underwent cesarean section and IH repair at the same time. Seven patients were managed and operated outside of our clinic. Only one patient who was operated externally needed small bowel resection (resection and reconstruction of the EE) due to severe ischemia caused by an obstructive jejunal mesenteric hernia. There were no deaths related to IH overall.

Discussion

The major findings of this observational cohort study, which included 785 consecutive patients with linear LRYGB in which 493 patients did not have mesenteric defects closed at the level of the EE and 292 received jejunal mesenteric defect closure during the primary operation, are as follows: (1) In our collective, the suture closure of the jejunal mesenteric defect leads to a reduction in absolute numbers of overall IH, but no statistically significant difference was found. (2) While IH appearance at the jejunal mesenteric space was reduced, a low rate of Petersen hernias in both groups was observed, as a T-shaped omental split was routinely performed in all patients.

The incidence of IH is a feared complication after LRYGB. According to the meta-analysis of Geubbels et al., the lowest rates of IH occur in antecolic gastric bypass with closure of both the jejunal mesenteric and the Petersen space [10]. Randomized controlled trials and large observational studies described IH rates slightly above 2% up to 5 years after surgery with closure of both gaps during primary surgery [13, 17]. In the current trial, reduction in IH rate was less pronounced. However, definition of IH differs widely in literature. In our collective, IH were clearly defined as manifest bowel herniation through the jejunal mesenteric or the Petersen space during revisional surgery. Open gaps without bowel herniation in symptomatic patients were assessed separately. Consequently, our IH rate might be underestimated, yet when considering all patients with open gaps and abdominal pain, intermittent IH cases would likely be overestimated given other causes of abdominal pain after LRYGB (e.g., symptomatic cholecystolithiasis). After approximately 3 years post-surgery, no more cases of IH occurred in the closure group. This disappearance of IH after mesenteric defect closure over time has been described in other collectives [17]. Unfortunately, our collective differs considerably in follow-up due to our change in closure strategy over time.

In our trial, we found that patients suffering from an IH or open mesenteric gap event had a lower BMI than patients without IH. Possibly, the higher weight loss associated with a loss of intra-abdominal fat mass leads to bigger mesenteric gaps, which may increase the risk for bowel herniation and strangulation.

Despite the advantages of reducing IH by closure of mesenteric defects, disadvantages caused by the closure technique itself have been described. In particular, early postoperative complications such as mesenteric hematoma and kinking are more frequently seen after closing mesenteric defects [13, 15]. However, Stenberg et al. showed that mesenteric defect closure can be performed safely, by focusing in particular on early postoperative small bowel obstruction by kinking of the EE [23].

In our cohort, we only observed very few early complications and kinking cases. This may be explained by our suture closure technique, which includes a fixation of the EE to the mesentery, preventing a high mobility of the anastomosis. Furthermore, we do not incise the mesentery at the level of the EE, and, consequently, the anastomosis does not drop below the level of the transverse colon and cannot move in all three dimensions. This leads to a stabilization of the EE, which may also explain the low rate of IH at the Petersen space in addition to the adhesions caused by the consequent T-shaped split of the omentum even in cases without massive central obesity. Assuming that most of our patients have an open gap behind the AL, the fixed EE blocks the bowel from herniating from the left to the right side of the abdominal cavity. The relatively high rate of IH at the level of the EE may also be explained by a learning curve of the suture closing technique. According to our current strategy, we take great care to close the defect precisely with small gaps between the stitches and suture up to the EE, including some sero-serosal stitches at the level of the EE.

Overall, the benefits of suturing the jejunal mesenteric space with a non-absorbable barbed thread during primary LRYGB were not as distinct in our collective as in other collectives [10, 12, 24].

This contribution underlines once more that even with primary closure of mesenteric defects, IH after LRYGB remains a problem of high priority, and exploratory laparoscopy should be performed in cases of suspicion of IH, no matter if the defects were closed during primary procedure or direct signs in computed tomography are not present.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, patients were not randomly assigned to both study arms, but we present a retrospective analysis of two cohorts before and after a change of treatment strategy. Therefore, follow-up time varies strongly amongst both study arms examined. In addition, the effect of the learning curve of the individual surgeons, especially for the closure technique of the jejunal mesenteric space, cannot be assessed utilizing our set of data. Moreover, data on IH was assessed from clinical follow-up data, and therefore, no routine, extra patient interviews, or questionnaires were carried out to explore possible IH symptoms. Finally, even though we assessed patients who received emergency surgery outside of our department, some cases of IH operated elsewhere could be missed in our assessment. Nevertheless, due to our long follow-up time, the good adherence of our patients to the clinic and the reliable communication system between bariatric surgery centers in our country, we estimate that we covered most of the postoperative late complications.

Conclusion

The closure of the jejunal mesenteric defect by non-absorbable suture may reduce the rate of IH at the jejunal mesenteric space after LRYGB. However, the beneficial effect in our collective is smaller than expected, particularly in patients with good weight loss. Petersen IH rate remained low by consequent T-shape split of the omentum without suturing of the defect.

References

Arterburn DE, Olsen MK, Smith VA, Livingston EH, Van Scoyoc L, Yancy WS, Eid G, Weidenbacher H, Maciejewski ML (2015) Association between bariatric surgery and long-term survival. JAMA 313:62–70

Schauer PR, Burguera B, Ikramuddin S et al (2003) Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg 238:467–484 discussion 84-5

Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP et al (2017) Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 376:641–651

Aminian A, Zajichek A, Arterburn DE, Wolski KE, Brethauer SA, Schauer PR, Kattan MW, Nissen SE (2019) Association of metabolic surgery with major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity. In: JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc. American Medical Association (AMA), pp 1271–1282

Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P et al (2014) Association of bariatric surgery with long-term remission of type 2 diabetes and with microvascular and macrovascular complications. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc 311:2297–2304

Wittgrove AC, Clark GW, Schubert KR (1996) Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux en-Y: technique and results in 75 patients with 3-30 months follow-up. Obes Surg 6:500–504

Lönroth H, Dalenbäck J, Haglind E, Lundell L (1996) Laparoscopic gastric bypass. Another option in bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc 10:636–638

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Formisano G, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N (2015) Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg 25:1822–1832

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Vitiello A, Higa K, Himpens J, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N (2018) IFSO worldwide survey 2016: primary, endoluminal, and revisional procedures. Obes Surg 28:3783–3794

Geubbels N, Lijftogt N, Fiocco M, Van Leersum NJ, Wouters MWJM, De Brauw LM (2015) Meta-analysis of internal herniation after gastric bypass surgery. Br J Surg 102:451–460

Abasbassi M, Pottel H, Deylgat B, Vansteenkiste F, Van Rooy F, Devriendt D, D’Hondt M (2011) Small bowel obstruction after antecolic antegastric laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass without division of small bowel mesentery: a single-centre, 7-year review. Obes Surg 21:1822–1827

Higa K, Ho T, Tercero F, Yunus T, Boone KB (2011) Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis 7:516–525

Stenberg E, Szabo E, Ågren G, Ottosson J, Marsk R, Lönroth H, Boman L, Magnuson A, Thorell A, Näslund I (2016) Closure of mesenteric defects in laparoscopic gastric bypass: a multicentre, randomised, parallel, open-label trial. Lancet 387:1397–1404

Amor IB, Kassir R, Debs T, Aldeghaither S, Petrucciani N, Nunziante M, Baqué P, Almunifi A, Gugenheim J (2019) Impact of mesenteric defect closure during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB): a retrospective study for a total of 2093 LRYGB. Obes Surg 29:3342–3347

Kristensen SD, Floyd AK, Naver L, Jess P (2015) Does the closure of mesenteric defects during laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery cause complications? Surg Obes Relat Dis 11:459–464

Stenberg E, Ottosson J, Szabo E, Näslund I (2019) Comparing techniques for mesenteric defects closure in laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery—a register-based cohort study. Obes Surg 29:1229–1235

Aghajani E, Nergaard BJ, Leifson BG, Hedenbro J, Gislason H (2017) The mesenteric defects in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 5 years follow-up of non-closure versus closure using the stapler technique. Surg Endosc 31:3743–3748

Aghajani E, Jacobsen HJ, Nergaard BJ, Hedenbro JL, Leifson BG, Gislason H (2012) Internal hernia after gastric bypass: a new and simplified technique for laparoscopic primary closure of the mesenteric defects. J Gastrointest Surg 16:641–645

Blockhuys M, Gypen B, Heyman S, Valk J, van Sprundel F, Hendrickx L (2019) Internal hernia after laparoscopic gastric bypass: effect of closure of the Petersen defect—single-center study. Obes Surg 29:70–75

Schneider R, Gass JM, Kern B, Peters T, Slawik M, Gebhart M, Peterli R (2016) Linear compared to circular stapler anastomosis in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass leads to comparable weight loss with fewer complications: a matched pair study. Langenbeck's Arch Surg 401:307–313

SMOB.ch-Start. http://smob.ch/de/. Accessed 12 Aug 2020

Prism-GraphPad. https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/. Accessed 15 Apr 2020

Stenberg E, Näslund I, Szabo E, Ottosson J (2018) Impact of mesenteric defect closure technique on complications after gastric bypass. Langenbeck's Arch Surg 403:481–486

Chowbey P, Baijal M, Kantharia NS, Khullar R, Sharma A, Soni V (2016) Mesenteric defect closure decreases the incidence of internal hernias following laparoscopic Roux-En-Y gastric bypass: a retrospective cohort study. Obes Surg 26:2029–2034

Availability of data and material

The datasets analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Universität Basel (Universitätsbibliothek Basel). The study was funded by institutional means.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S., M.S., and J.K. performed the data extraction and the analysis. R.S. and R.P. were involved in planning and supervised the work. R.S drafted the manuscript and the figures. M.K., J.K., T.P., and B.W. aided in interpreting the results and worked on the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (EKNZ 2018/00356) and performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals as a mandatory part of quality control in our hospital.

Consent for publication

All authors have read the final version of the article and have provided consent for the article to be published in Langenbeck’s Archives of Surgery.

Conflict of interest

R.S. reports grants from University of Basel; grants from Department of Surgery, University Hospital Basel; grants from SFCS (Stiftung zur Förderung von chirurgischer Forschung und Spitalmanagement); grants from Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft Basel; and grants from Gebauer Stiftung, outside the submitted work. B.W. reports grants from Swiss National Science Foundation; grants from Synergia; and grants from Botnar Foundation, outside the submitted work. R.P. reports grants and other from Johnson and Johnson, outside the submitted work. All other authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schneider, R., Schulenburg, M., Kraljević, M. et al. Does the non-absorbable suture closure of the jejunal mesenteric defect reduce the incidence and severity of internal hernias after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass?. Langenbecks Arch Surg 406, 1831–1838 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02180-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02180-2