Abstract

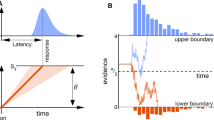

In primates, it is well known that there is a consistent relationship between the duration, peak velocity and amplitude of saccadic eye movements, known as the ‘main sequence’. The reason why such a stereotyped relationship evolved is unknown. We propose that a fundamental constraint on the deployment of foveal vision lies in the motor system that is perturbed by signal-dependent noise (proportional noise) on the motor command. This noise imposes a compromise between the speed and accuracy of an eye movement. We propose that saccade trajectories have evolved to optimize a trade-off between the accuracy and duration of the movement. Taking a semi-analytical approach we use Pontryagin’s minimum principle to show that there is an optimal trajectory for a given amplitude and duration; and that there is an optimal duration for a given amplitude. It follows that the peak velocity is also fixed for a given amplitude. These predictions are in good agreement with observed saccade trajectories and the main sequence. Moreover, this model predicts a small saccadic dead-zone in which it is better to stay eccentric of target than make a saccade onto target. We conclude that the main sequence has evolved as a strategy to optimize the trade-off between accuracy and speed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bahill AT, Clark MR, Stark L (1975) Dynamic overshoot in saccadic eye movements is caused by neurological control signal reversals. Exp Neurol 48:107–122

Baloh RW, Sills AW, Kumley WE, Honrubia V (1975) Quantitative measurement of saccade amplitude, duration, and velocity. Neurology 25:1065–1070

Becker W (1989). Metrics. In: Wurtz R, Goldberg M (eds). The neurobiology of saccadic eye movements. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 13–67

van Beers RJ (2003) The origin of variability in eye position during visual fixation. Society for Neuroscience, Washington, p. Program No. 187–188

van Beers RJ, Baraduc P, Wolpert DM (2002) Role of uncertainty in sensorimotor control. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 357:1137–1145

van Beers RJ, Haggard P, Wolpert DM (2004) The role of execution noise in movement variability. J Neurophysiol 91:1050–1063

Bryson AE, Ho YC (1975) Applied optimal control. Wiley, New York

Burdet E, Osu R, Franklin DW, Milner TE, Kawato M (2001) The central nervous system stabilizes unstable dynamics by learning optimal impedance. Nature 414:446–449

Burr DC, Ross J (1982) Contrast sensitivity at high velocities. Vision Res 22:479–484

Buswell GT (1935) How people look at pictures. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Chung STL, Bedell HE (1998) Vernier acuity and letter acuities for low-pass filtered moving stimuli. Vision Res 38:1967–1982

Clark MR, Stark L (1975) Time optimal behavior of human saccadic eye movement. IEEE Trans Automat Control AC-20:345–348

Collewijn H, Erkelens CJ, Steinman RM (1988) Binocular coordination of human horizontal saccadic eye-movements. J Physiol 404:157–182

Enderle JD, Wolfe JW (1987) Time-optimal control of saccadic eye-movements. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 34(1):43–55

Epelboim J, Steinman RM, Kowler E, Pizlo Z, Erkelens CJ, Collewijn H (1997) Gaze-shift dyndamics in two kinds of sequential looking tasks. Vision Res 37:2597–2607

Fitts PM (1954) The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movements. J Exp Psychol 47:381–391

Flash T, Hogan N (1985) The co-ordination of arm movements: an experimentally confirmed mathematical model. J Neurosci 5:1688–1703

Fuchs AF, Binder MD (1983) Fatigue resistance of human extraocular muscles. J Neurophysiol 49:28–34

Groh JM, Sparks D (1996) Saccades to somatosensory targets. I. Behavioural characteristsics. J Neurophysiol 75:412–427

Hamilton AF, Wolpert DM (2002) Controlling the statistics of action: obstacle avoidance. J Neurophysiol 87:2434–2440

Hammett ST, Georgeson MA, Gorea A (1998) Motion blur and motion sharpening: temporal smear and local contrast non-linearity. Vision Res 38:2099–2108

Happee R (1992) Time optimality in the control of human movements. Biol Cybern 66:357–366

Harris CM (1995) Does saccadic under-shoot minimize saccadic flight-time? A Monte-carlo study. Vision Res 35:691–701

Harris CM (1998) On the optimal control of behaviour: a stochastic perspective. J Neurosci Meth 83:73–88

Harris CM (2002) Temporal uncertainty in reading the neural code (proportional noise). Biosystems 67:85–94

Harris CM, Wolpert DM (1998) Signal-dependent noise determines motor planning. Nature 394:780–784

Harwood M, Mezey L, Harris CM (1999) The spectral main sequence of human saccades. J Neurosci 19:9096–9106

Herse PR, Bedell HE (1989) Contrast sensitivity for letter and grating targets under various stimulus conditions. Optom Vision Sci 66:774–781

Hogan N (1984) An organizing principle for a class of voluntary movements. J Neurosci 4:2745–2754

Jones KE, De AF, Hamilton C, Wolpert DM (2002) Sources of signal-dependent noise during isometric force production. J Neurophysiol 88:1533–1544

Kuo AD (1995) An optimal-control model for analyzing human postural balance. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 42:87–101

Ludvigh E (1941) Extrafoveal visual acuity as measured with Snellen test-letters. Am J Ophthalmol 24:303–310

Matthews PBC (1996) Relationship of firing intervals of human motor units to the trajectory of post-spike after-hyperpolarization and synaptic noise. J Physiol 492(2):597–628

Morgan MJ, Watt RJ, McKee SP (1983) Exposure duration affect the sensitivity of vernier acuity to target motion. Vision Res 23:541–546

Nelson WL (1983) Physical principles for economies of skilled movements. Biol Cybern 46:135–147

van Opstal AJ, van Gisbergen JA (1989) Scatter in the metrics of saccades and properties of the collicular motor map. Vision Res 29:1183–1196

Pandy MG (2001) Computer modeling and simulation of human movement. Ann Rev Biomed Eng 3:245–273

Quaia C, Lefevre P, Optican LM (1999) Model of the control of saccades by superior colliculus and cerebellum. J Neurophysiol 82:999–1018

Rashbass C (1961) The relationship between saccadic and smooth tracking eye movements. J Physiol 159:326–338

Schmidt RA, Zelaznik H, Hawkins B, Franks JS, Quinn JTJ (1979) Motor output variability: a theory for the accuracy of rapid motor acts. Psychol Rev 86(5):415–451

Smit AC, Van Gisbergen JA, Cools AR (1987) A parametric analysis of human saccades in different experimental paradigms. Vision Res 27:1745–1762

Todorov E, Jordan MI (2002) Optimal feedback control as a theory of motor coordination. Nat Neurosci 5:1226–1235

Uno Y, Kawato M, Suzuki R (1989) Formation and control of optimal trajectory in human multijoint arm movement. Minimum torque-change model. Biol Cybern 61:89–101

Weber H, Aiple F, Fischer B, Latanov A (1992) Dead zone for express saccades. Exp Brain Res 89:214–222

Westheimer G, McKee P (1975) Visual acuity in the presence of retinal-image motion. JOSA 65:847–850

Wyman D, Steinman RM (1973a) Latency characteristics of small saccades. Vision Res 13:2173–2175

Wyman D, Steinman RM (1973b) Small step tracking: implications for the oculomotor “dead zone”. Vision Res 13:2165–2172

Zambarbieri D, Schmid R, Magenes G, Prablanc C (1982) Saccadic responses evoked by presentation of visual and auditory targets. Exp Brain Res 47:417–427

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harris, C.M., Wolpert, D.M. The Main Sequence of Saccades Optimizes Speed-accuracy Trade-off. Biol Cybern 95, 21–29 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00422-006-0064-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00422-006-0064-x