Abstract

Purpose

Force enhancement is the phenomenon of increased forces during (transient force enhancement; tFE) and after (residual force enhancement; rFE) eccentric muscle actions compared with fixed-end contractions. Although tFE and rFE have been observed at short and long muscle lengths, whether both are length-dependent remains unclear in vivo.

Methods

We determined maximal-effort vastus lateralis (VL) force-angle relationships of eleven healthy males and selected one knee joint angle at a short and long muscle lengths where VL produced approximately the same force (85% of maximum). We then examined tFE and rFE at these two lengths during and following the same amount of knee joint rotation.

Results

We found tFE at both short (11.7%, P = 0.017) and long (15.2%, P = 0.001) muscle lengths. rFE was only observed at the long (10.6%, P < 0.001; short: 1.3%, P = 0.439) muscle length. Ultrasound imaging revealed that VL muscle fascicle stretch magnitude was greater at long compared with short muscle lengths (mean difference: (tFE) 1.7 mm, (rFE) 1.9 mm, P ≤ 0.046), despite similar isometric VL forces across lengths (P ≥ 0.923). Greater fascicle stretch magnitude was likely to be due to greater preload forces at the long compared with short muscle length (P ≤ 0.001).

Conclusion

At a similar isometric VL force capacity, tFE was not muscle-length-dependent at the lengths we tested, whereas rFE was greater at longer muscle length. We speculate that the in vivo mechanical factors affecting tFE and rFE are different and that greater stretch of a passive component is likely contributing more to rFE at longer muscle lengths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eccentric muscle actions are important for absorbing kinetic energy and the underlying mechanisms contributing to their unique properties have been frequently examined under in vitro conditions. One unique property is that during and following an eccentric muscle action, a muscle can produce enhanced force relative to its isometric force at the same muscle length and activation level (Edman et al. 1978; Cook and McDonagh 1995). Enhanced forces during and following an eccentric muscle action are referred to as transient force enhancement (tFE) and residual force enhancement (rFE), respectively. Both tFE and rFE have been observed across muscle structural scales from single sarcomeres (Leonard et al. 2010) and isolated animal (Abbott and Aubert 1952) and human (Pinnell et al. 2019) fibres to whole human muscles (Westing et al. 1988; Cook and McDonagh 1995) working in vivo and are, thus, known properties of skeletal muscle.

tFE and rFE are influenced by different mechanical factors. tFE is stretch-amplitude- and stretch-velocity-dependent (Edman et al. 1978; Dudley et al. 1990; Lombardi and Piazzesi 1990; Lee and Herzog 2002). However, the stretch-velocity dependence of tFE is not apparent from above ~ 0.2–0.5 times the muscle’s maximum shortening velocity in vitro (Edman et al. 1978; Harry et al. 1990; Linari et al. 2004). rFE is independent of stretch velocity (Edman et al. 1978; Tilp et al. 2009), but dependent on stretch amplitude, where rFE generally increases with increasing stretch amplitudes (Edman et al. 1978, 1982) to some critical value (Bullimore et al. 2007; Hisey et al. 2009). However, some in vivo findings suggest that rFE is only stretch-amplitude-dependent under specific circumstances, which depend on the muscles of interest and the amount of joint rotation (whereby larger joint rotation magnitudes are assumed to cause larger amplitude muscle stretches) (Lee and Herzog 2002; Oskouei and Herzog 2006; Hahn et al. 2007; Tilp et al. 2009). The discrepancy between the mechanical factors that affect in vitro and in vivo rFE might be due to both neural and mechanical factors, such as differences in how and when the muscle is activated and the amount of muscle–tendon unit (MTU) compliance, all of which may affect the amplitude and velocity of muscle stretch.

Muscle force production during and after an eccentric muscle action also depends on where the muscle operates on its force–length relationship. For in vitro and in situ studies, where muscle lengths can be well controlled, greater tFE and rFE typically occur at longer sarcomere and fascicle lengths (Granzier et al. 1989; Hisey et al. 2009; Scott et al. 1996). The few in vivo human studies that have tested the influence of muscle length on tFE and rFE show conflicting results. During in vivo multi-joint contractions, tFE has been observed at longer muscle lengths only (Hahn et al. 2014). However, during single-joint contractions, tFE has been found at both short and long muscle lengths when the preloads (i.e., the torque before the stretch starts) is similar to the angle-joint-specific maximum isometric force (Linnamo et al. 2006). In vivo studies showed that greater rFE occurs at short and long muscle lengths, but with grater rFE at long compared with short muscle lengths (Shim and Garner 2012; Power et al. 2013; Fukutani et al. 2017). Another in vivo study on the elbow flexors did not observe rFE at short or long muscle lengths (de Brito Fontana et al. 2018). The discrepancies between in vivo studies might be because of differences in the amplitude and/or velocity of muscle stretch between short and long muscle lengths, or because of differences in the muscle’s isometric force capacity between short and long muscle lengths. The discrepancies between in vivo and in vitro findings might also arise due to differences in the magnitude and velocity of muscle stretch and/or how muscle force is transmitted across the joint (Ruttiman et al. 2019) and differences in how muscles are activated (voluntary contractions versus electrical stimulation). These factors limit the ecological validity of in vitro tFE and rFE findings and suggest that more carefully controlled in vivo studies are required to assess the relevance of tFE and rFE for everyday human movement.

Due to the conflicting tFE and rFE findings at short and long in vivo muscle lengths, we sought to investigate tFE and rFE on the ascending (i.e. short muscle length) and descending limbs (i.e. long muscle length) of the estimated vastus lateralis (VL) force–angle relationship following the same amount of knee joint rotation. To ensure that tFE and rFE were not influenced by differences in the muscle’s isometric force capacity at short and long muscle lengths, we matched the VL’s isometric force capacity at the short and long muscle length. Due to the various mechanisms predicted to contribute to tFE and rFE, including (1) sarcomere length non-uniformities at longer muscle lengths (Morgan 1990), (2) inappropriate cross-bridge attachment at shorter muscle lengths (Scott et al. 1996), (3) decreased myofilament lattice spacing at longer muscle lengths (Edman 1999), and (4) increased titin forces at longer muscle lengths (Flann et al. 2011), we expected greater tFE at long compared with short muscle lengths. For these same reasons, we expected greater rFE at a long muscle length considering that enhanced forces following stretch are related to the enhanced forces during stretch (Bullimore et al. 2007; Paternoster et al. 2016).

Methods

Participants

Twelve healthy male subjects (age 28.4 ± 2.6 years; height 182.1 ± 4.9 cm; weight 80.8 ± 8.5 kg) gave free written informed consent prior to participating in the study. All participants were free of knee injuries and neuromuscular disorders. All experimental procedures were approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Sport Science at Ruhr University Bochum, which conformed with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental set-up

Participants performed knee extension contractions with their right leg while sitting in a reclined position with their hip fixed at 100° of flexion on the seat of a motorized dynamometer (IsoMed2000, D&R Ferstl, GmbH, Hemau, GER). The participant’s right lower leg was fixed with Velcro around the mid-shank to a cushioned attachment that was connected to the crank arm of the dynamometer. Two shoulder restraints and one waist strap were used to secure participants firmly in the seat of the dynamometer. Participants folded their arms across their chest prior to each contraction to limit accessory movements. To compensate for the knee joint rotation that occurs during activation of the knee extensors (Arampatzis et al. 2004; Bakenecker et al. 2019), the knee joint and the dynamometer axes of rotation were aligned during a maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) at 60° knee flexion.

Torque measurements

The dynamometer was used to measure the crank arm angle and the net knee joint torque produced during stretch, stretch–hold and fixed-end contractions. Torque and angle data were sampled at 1 kHz and synchronised using a 16-bit Power 1401 and Spike2 data collection system (Cambridge Electronic Design, UK). To later account for the effects of gravity and passive joint torque on the torque measurements, five passive knee extensions (5°s−1) were performed over the whole knee joint range of motion (ROM) while participants were instructed to relax and EMG signals were visually inspected by the investigator.

Knee joint kinematics

Due to soft tissue deformation and dynamometer compliance during MVCs (Arampatzis et al. 2004), knee joint angles can differ from the crank arm angle of the dynamometer. We, therefore, determined the actual knee joint angle across contraction conditions using two inertial measurement units (IMU) (myon AG, Schwarzenberg, Switzerland) positioned on the shank and the thigh of the right leg. IMUs were secured over these segments where the least soft tissue movement occurred (i.e. on the tibia close to the knee and approximately 5 cm below the greater trochanter) using elastic straps and sports tape. Data were sampled at 143 Hz using iSen software (version 3.8 beta, STT Systems, San Sebastian, Spain) and synchronised with all other data in Spike2 software via digital pulses from the IMU and ultrasound systems.

Surface electromyography

Surface EMG (AnEMG12, OT Bioelettronica, IT) was used to record the muscle activities of the vastus lateralis (VL), rectus femoris (RF) and vastus medialis (VM) of the right leg. After skin preparation (i.e. shaving, abrading and swabbing the skin with antiseptic), two surface electrodes (8 mm recording diameter, Ag/AgCl, Kendall H124SG, Massachusetts, USA) were placed over the muscles of interest according to SENIAM guidelines (Hermens et al. 2000) with a 2 cm inter-electrode distance. A single reference electrode was secured to the right-sided fibular head. EMG signals were band-pass filtered between 0.01 and 4.4 kHz and amplified 1000 times (AnEMG12, OT Bioelettronica, IT), before being sampled at 2 kHz using the hardware and software described above.

Ultrasound imaging

To image the muscle fascicles of VL during stretch, stretch–hold and fixed-end contractions, a PC-based ultrasound system (LogicScan 128 CEXT-1Z Kit, Telemed, Vilnius, Lithuania) with a flat-sided 96-element transducer (LV7.5/60/96, B-mode, 8.0 MHz, 60 mm depth; Telemed, Vilnius, Lithuania) was used. The transducer captured images at ~ 62 Hz and was placed over the mid-belly of VL (Sharifnezhad et al. 2014). The location of the transducer on the skin was secured using a custom 3D-printed plastic frame and adhesive tape. The ultrasound system generated a digital pulse that was used to synchronize all digital signals to a common start and end time. VL fascicle lengths were linearly extrapolated and pennation angles were calculated relative to the horizontal in each image offline using previously described ultrasound tracking software and procedures (Gillett et al. 2013; Farris and Lichtwark 2016). During fascicle shortening, lengthening and isometric-hold phases, a frame-by-frame manual digitisation was performed if fascicle endpoints were incorrectly identified during the semi-automated tracking process.

Experimental protocol

The entire experiment consisted of two familiarization sessions and two test sessions. Familiarization helped participants to become comfortable with the dynamometer and with performing MVCs during stretch, stretch–hold and fixed-end contractions. Each experimental session started with a standardised warm-up (walking) and five submaximal fixed-end knee extension contractions (~ 50–80% of perceived maximum effort) to precondition the MTU (Maganaris et al. 2002). Contractions were performed with standardized verbal encouragement from the investigator, while participants received real-time visual feedback of their net knee joint torque (Gandevia 2001).

Test session 1: determination of force-angle relationship

We estimated the participants’ individual force–angle relationships to match the muscle-specific force produced by the VL at short and long muscle lengths. Participants performed maximum voluntary isometric knee extension contractions at six knee flexion angles in increments of 10° ranging from 40° to 90°. To estimate in vivo VL muscle force, the peak knee extension torque at each joint angle was multiplied by literature-based values of the VL’s physiological cross-sectional area (PCSA) relative to the quadriceps’ PCSA (34%) (Akima et al. 1995) and then divided by the angle-specific patella tendon moment arm from the recommended mean patella tendon moment arm function provided by Bakenecker et al. (2019).

Test session 2: Determination of transient and residual force enhancement at short and long muscle lengths with a similar VL isometric force capacity

Using the estimated force–angle relationship determined in session 1, one knee joint angle on either side of the plateau of the force–angle relationship where VL produced the same estimated muscle force (85% of maximum VL force) was selected as the reference knee joint angle for the fixed-end contractions at a short and long muscle length. This reference knee joint angle was used as the target knee joint angle during stretch contractions and as the target knee joint angle following stretch in stretch–hold contractions at a short and long muscle length (see Fig. 1). Stretch contractions at short and long muscle lengths were performed with an amplitude of 25° knee flexion (15° to the target knee joint angles) to estimate transient force enhancement (tFE). Stretch–hold contractions at short and long muscle lengths were performed with an amplitude of 15° knee flexion to the final knee joint angles and followed by an isometric-hold phase to estimate residual force enhancement (rFE) (see Fig. 2). Both stretch and stretch–hold contractions were performed with an angular velocity of 60°s−1 and knee joint rotation was triggered manually by the investigator when participants reached a torque plateau close to their angle-specific maximum knee extension torque as determined in test session 1. All three contraction conditions (i.e., stretch, stretch–hold and fixed-end reference contractions) were performed at least three times in a randomised order and participants received at least 3 min of rest between contractions.

Mean normalized fitted vastus lateralis (VL) force-angle relationship (solid line) across all participants (N = 12) with lower and upper 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines). Two different knee joint angles (i.e. the short and long muscle lengths), where the VL produced the same estimated muscle force (85% of maximum VL force, Fmax), were selected as the target knee joint angles for the stretch, stretch–hold and fixed-end reference contractions

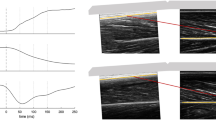

Exemplar (n = 1) active knee extension torque-time traces for the stretch (blue), stretch–hold (green) and fixed-end reference contractions (black) at the short (a) and long (b) muscle lengths, and the corresponding changes in knee joint angle for these three contraction conditions at short (c) and long (d) muscle lengths. The vertical grey lines and grey shaded areas show the time points/time intervals where torque was analysed to evaluate tFE and rFE

Data analysis

Torque data were filtered using a dual-pass fourth-order 20 Hz low-pass Butterworth filter. Knee angle and crank arm angle data were filtered using the same filter with a 15 Hz cut-off frequency. To determine knee extension torque during the MVCs in test session 1, co-contraction was assumed to be negligible and the angle-specific torque from the fifth passive knee extension (Esteki and Mansour 1996; Lieber et al. 2000) was subtracted from the highest MVC torque value obtained at each tested knee joint position. VL fascicle length data and knee joint torque data during the passive rotations were used to check if it was necessary to account for changes in passive tension in the VL during the MVC trials, but we did not test at long enough muscle lengths to observe worthwhile changes in passive knee joint torque. Torque data obtained during MVCs in test session 1 and during stretch, stretch–hold and fixed-end reference contractions in test session 2 was subsequently used to estimate VL muscle force as described in test session 1.

Force–angle relationship

For each tested knee joint angle, the estimated maximum VL force was normalised to the maximum VL force over all tested knee joint angles. Following this, a second-order exponential curve was fitted to the estimated VL force–angle data.

Transient and residual force enhancement

tFE was calculated as the normalised difference in VL force at the respective target knee joint angle between the stretch and fixed-end reference contractions. rFE was calculated as the normalised difference in mean VL force from 2.5 to 3.0 s after stretch at the respective target knee joint angle between the stretch–hold and fixed-end reference contractions, which is in line with previous studies (Hahn et al. 2010, 2012).

Preload forces

VL preload forces before the start of knee joint rotation during the stretch and stretch–hold contractions were quantified at the last time point before the crank arm changed position. The start of crank arm rotation was defined as the time when its derived angular velocity was ≥ 0.3°s−1.

EMG activity

EMG signals from the superficial quadriceps muscles (VL, RF, VM) had the DC offset removed and were then smoothed using a moving root-mean-square (RMS) amplitude calculation of 100 ms. Superficial quadriceps muscle activities during the stretch contractions were then quantified as the EMG RMS value at the target knee joint angle, and for stretch–hold contractions, was quantified by taking the mean EMG RMS value from 2.5–3 s after stretch. Muscle activity during stretch and stretch–hold contractions was then compared with the time-matched muscle activity during the fixed-end contractions.

Fascicle behaviour

Fascicle length data were filtered using a dual-pass fourth-order 5 Hz (Bohm et al. 2018) low-pass Butterworth filter. Across contraction conditions, VL fascicle length data were analysed in the same way as the torque data to determine if fascicle lengths were similar between the stretch and fixed-end contractions and stretch–hold and fixed-end contractions. For stretch and stretch–hold contractions, the start of fascicle lengthening was determined as the time point when the VL fascicle velocity was ≥ 0.05 mms−1 and for the stretch–hold contractions only, the end of fascicle lengthening was determined as the time point when VL fascicle velocity was ≤ 0.05 mms−1. During the stretch contractions, the magnitude of fascicle stretch was measured from the time point defined above to the time point where the target joint angle was reached. For stretch–hold contractions, the magnitude of fascicle stretch was determined from the start to end of fascicle lengthening.

Fascicle shortening during the initial phase of force development was also measured across contraction conditions as the change in fascicle length from initial to minimum fascicle length. Initial fascicle length was defined as the mean value over the first 1.5 s of fascicle length data where subjects were instructed to relax and EMG signals were inspected by the investigator. To determine the stretch velocity of the VL fascicles during the stretch and stretch–hold contractions, the filtered fascicle length data were differentiated. Stretch velocity during the stretch contractions was then defined as the VL fascicle velocity at the time point where the target joint angle was reached. Stretch velocity during the stretch–hold contractions was defined as the mean VL fascicle velocity over the period of fascicle lengthening.

For six participants (the reduced sample size was due to time drift in the IMU signals during stretch and stretch–hold contractions), internal work of the VL muscle fascicles was also calculated by integrating the estimated VL fascicle force over the fascicle length change during the initial phase of force development. VL fascicle force was calculated by dividing the VL muscle force by the cosine of the measured fascicle angle, which was quantified relative to the deep aponeurosis of VL.

Statistical analysis

All data processing and analysis were performed using custom-written scripts in Matlab software (Mathworks, R2016b, Natick, MA). Based on the calculations provided by Leys et al. (2013), one participant was defined as an outlier and removed from statistical analysis. Outliers were defined as values exceeding three times the median absolute deviation. Data were tested for normality using Shapiro–Wilk normality tests. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs were performed to identify differences in VL force, superficial quadriceps muscle activities and VL fascicle lengths between stretch, stretch–hold and fixed-end contractions between muscle lengths (contraction condition × muscle length). The same test was used to identify differences in VL fascicle shortening and VL fascicle work between stretch, stretch–hold and fixed-end contractions between muscle lengths. If a contraction condition main effect or significant interaction was observed, post hoc comparisons with Sidak adjustments were performed. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs were also used to identify differences in VL fascicle stretch, VL preload force and VL fascicle stretch velocity during stretch and stretch–hold contractions across muscle lengths. Paired t tests were used to identify differences in tFE and rFE between the short and long muscle lengths. Pearson or Spearman (if normality was violated) correlation coefficients were calculated to test the strength of the relationships between tFE and rFE, between tFE/rFE and fascicle stretch magnitude and between VL preload force and fascicle stretch magnitude across both muscle lengths (i.e., pooled data). The alpha level was set at P < 0.05 and statistical analyses were performed using commercially available software (GraphPad Prism 8, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Transient force enhancement

Mean time-matched VL force during the fixed-end reference contractions was 1910 ± 382 N at the short muscle length and 1931 ± 408 N at the long muscle length, which was not significantly different (mean difference 3.1 ± 2.4%; P = 0.567). Mean VL force during the stretch condition was 2112 ± 348 N at the short muscle length and 2228 ± 548 N at the long muscle length. This resulted in tFE of 11.6 ± 12.8% at the short muscle length (P = 0.03) and 15.2 ± 11.8% at the long muscle length (P = 0.003) (Fig. 3), which was not significantly different between muscle lengths (P = 0.438). The corresponding net knee joint torques are shown in Table 1.

Individual and mean transient force enhancement (tFE; dots) and residual force enhancement (rFE; triangles) magnitudes at the short (grey) and long (black) muscle lengths. Filled symbols represent the individual values and horizontal lines indicate the group mean for each condition (N = 11). Grey lines and black numbers distinguish between participants. *Indicates a significant difference compared with time-matched fixed-end conditions at the same muscle length (P < 0.05)

Residual force enhancement

Mean time-matched VL force during the fixed-end reference contractions was 1934 ± 404 N at the short muscle length and 1877 ± 396 N at the long muscle length, which was not significantly different (mean difference 5.2 ± 3.2%; P = 0.143). Mean VL force during the stretch–hold condition was 1957 ± 398 N at the short muscle length and 2066 ± 386 N at the long muscle length. This resulted in rFE of 1.3 ± 3.1% at the short muscle length (P = 0.366) and 10.7 ± 5.5% at the long muscle length (Fig. 3) (P < 0.001), which was significantly different between muscle lengths (P < 0.001). The corresponding net knee joint torques are shown in Table 1. Across both muscle lengths, we found no significant correlation between tFE and rFE (r = 0.18, 95% CI: -0.26 to 0.56, P = 0.428).

Preload forces

Mean VL preload force during the stretch contractions was 1476 ± 270 N at the short muscle length and 2082 ± 536 N at the long muscle length (mean difference 41.3 ± 23.4%), which was significantly different between muscle lengths (P < 0.001). VL preload force during stretch–hold contractions was 1439 ± 333 N at the short muscle length and 2100 ± 450 N at the long muscle length (mean difference 48.9 ± 29.6%), which was also significantly different between muscle lengths (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in preload force between stretch and stretch–hold contractions at short (P = 0.972) or long muscle lengths (P = 0.994).

Muscle activity

There were no significant differences in muscle activity for any of the superficial quadriceps muscles (VL, RF and VM) for the stretch condition compared with the time-matched fixed-end condition at the short (VL: P = 0.975; RF: P = 0.314; VM: P = 0.551) or long (VL: P = 0.792; RF: P = 0.636; VM: P = 0.777) muscle lengths. We also found no significant differences in muscle activity of the VL, RF and VM for the stretch–hold condition compared with the time-matched fixed-end condition at the short (VL: P = 0.382; RF: P = 0.291; VM: P = 0.958) or long (VL: P = 0.271; RF: P = 0.861; VM: P = 0.097) muscle lengths. Detailed results are shown in Table 1.

Fascicle behaviour

During the stretch contractions, VL muscle fascicles were stretched 2.2 ± 1.5 mm at the short muscle length compared with 3.9 ± 1.9 mm at the long muscle length, which was significantly different between muscle lengths (P = 0.046). For stretch–hold contractions, VL muscle fascicles were stretched by 2.2 ± 1.8 mm at the short muscle length and 4.1 ± 2.4 mm at the long muscle length, which was also significantly different between muscle lengths (P = 0.016) (Table 2 and Fig. 4). A comparison of VL fascicle shortening at short and long muscle lengths between stretch, stretch–hold and fixed-end contractions during the initial phase of force development revealed no significant main effect of contraction condition (P = 0.952), a significant main effect of muscle length (P = 0.047) and no significant interaction (P = 0.550) (Table 2). Post hoc comparisons revealed no significant differences in VL fascicle shortening between muscle lengths during stretch (P = 0.416), stretch–hold (P = 0.891) or fixed-end (P = 0.292) contractions.

Individual and mean magnitudes of VL muscle fascicle stretch during the stretch (tFE; dots) and stretch–hold contractions (rFE; triangles) at the short (grey) and long (black) muscle lengths. Filled symbols represent the individual values and horizontal lines indicate the group mean for each condition (N = 11). Grey lines and black numbers distinguish between participants. *Indicates a significant difference between the short and long muscle length (P < 0.05)

Across muscle lengths, there were no significant differences in absolute VL fascicle lengths between stretch (P = 0.610) or stretch–hold (P = 0.074) contractions and the fixed-end reference contractions. We found significantly lower VL fascicle stretch velocities during stretch contractions (P = 0.026) at the short compared with the long muscle length, but no significant difference in VL fascicle stretch velocity was observed during stretch–hold contractions (P = 0.067) between the short and long muscle length (Table 2). Across muscle lengths, we found no significant correlations between VL fascicle stretch magnitude and tFE (r = − 0.01, 95% CI − 0.43 to 0.41, P = 0.956) and between VL fascicle stretch velocity and tFE (r = 0.03, 95% CI − 0.39 to 0.45, P = 0.880). However, there were significant moderate positive correlations between VL fascicle stretch magnitude and rFE (r = 0.53, 95% CI 0.13–0.78, P = 0.012) (Fig. 5) and between VL preload force and VL fascicle stretch magnitude across muscle lengths (rho = 0.51, 95% CI 0.24–0.70, P < 0.001).

Kinematics

The mean knee joint angle determined from the IMUs for the fixed-end reference contractions was 39.8 ± 2.9° and 69.3 ± 9.4° for the short and long muscle lengths, respectively. The contraction-induced knee joint rotation (despite fixed-end conditions) was 19.2 ± 4.0° and 15.3 ± 2.9° at the short and long muscle lengths, respectively. During the preload phase of the stretch and stretch–hold contractions at the short muscle lengths, the knee joint rotated 17.8 ± 3.8° and 16.2 ± 4.2°, respectively. During the preload phase of the stretch and stretch–hold contractions at the long muscle lengths, the knee joint rotated 17.3 ± 5.6° and 17.1 ± 2.2°, respectively.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to investigate if tFE and rFE differs following the same knee joint rotation magnitude at short and long muscle lengths with the same estimated isometric VL force capacity. We found that VL force during stretch contractions (tFE) was significantly larger than the time-matched VL force during fixed-end contractions at both short and long muscle lengths and that there was no significant difference in tFE between muscle lengths. In contrast, VL force during stretch–hold contractions (rFE) was only significantly larger than the time-matched VL force during fixed-end contractions at the long muscle length, resulting in significantly greater rFE at the long compared with short muscle length. Therefore, at the muscle lengths tested here, rFE, but not tFE, was muscle-length-dependent, which suggests that the in vivo mechanical factors contributing to tFE and rFE are different.

In this study, we observed VL forces that were enhanced by 12% at a short muscle length and by 15% at a long muscle length during stretch contractions relative to maximum-effort fixed-end contractions at matched target joint angles. This is in accordance with other in vivo studies on the knee extensors, which reported enhanced forces ranging 10–30% during maximum-effort stretch contractions relative to corresponding fixed-end reference contractions (Finni et al. 2003; Hahn et al. 2007, 2010). Similar to our study, these studies incorporated participant familiarisation into their experimental design and ensured high preloads prior to joint rotation, which are crucial factors when investigating tFE and rFE (Hahn 2018). Other studies that have not observed enhanced forces during stretch contractions at short or long muscle lengths (Westing et al. 1988; Komi et al. 2000; Doguet et al. 2017) may be confounded by inadequate participant familiarisation and/or insufficient preloads prior to joint rotation. For example, in vivo tFE may not be studied if there are low preloads before joint rotation, which can result in concentric and not eccentric fascicle behaviour during MTU stretch due to increased MTU compliance at low muscle forces (Hahn 2018). This argument is supported by findings from Linnamo et al. (2006), who only observed tFE in participants who reached preload forces within ± 5% of their angle-specific maximum isometric force before joint rotation. Our results further confirm that concentric muscle fascicle behaviour of the VL during the active MTU lengthening phase can be completely avoided with high preloads (Fig. 2).

Transient force enhancement

In vitro studies have previously revealed two mechanisms that are associated with enhanced forces during stretch (tFE) contractions: increased cross-bridge forces (Huxley and Simmons 1971) and increased passive forces caused by stretch of the spring-like muscle protein titin (Granzier and Labeit 2006). Regarding a length dependency of these mechanisms, it has been shown that there is inappropriate cross-bridge attachment at shorter muscle lengths (Scott et al. 1996), decreased myofilament lattice spacing at longer muscle lengths (Edman 1999) and increased titin forces at longer muscle lengths (Flann et al. 2011). Therefore, tFE during stretch contractions is expected to be larger when the muscle is stretched at longer lengths. However, our results show no significant difference in tFE between the muscle lengths we tested (Fig. 3), with only a 3.6% MVC mean difference between short and long muscle lengths, which suggests that tFE is not muscle-length-dependent in the knee extensors over the muscle length range we tested here.

Our tFE findings contradict those from in vitro and in situ studies, which suggest tFE increases with increasing muscle length (Granzier et al. 1989; Scott et al. 1996). The discrepancy could be due to differences in how the muscle is activated during in vitro and in vivo experiments. Some studies (Westing et al. 1988; Dudley et al. 1990; Webber and Kriellaars 1997; Babault et al. 2001) suggest that the absence of tFE during in vivo stretch contractions arises due to neural inhibition and that neural inhibition might be greater at longer muscle lengths (Linnamo et al. 2006). These studies defined neural inhibition as the difference in maximal torque produced during electrical stimulation compared with voluntary contraction. Although we did not assess neural inhibition in this way, neural inhibition might have reduced tFE at the long muscle length, resulting in no difference in tFE between muscle lengths. However, our EMG data show no significant differences in muscle activity of VL, RF and VM during stretch contractions compared with the corresponding fixed-end contractions at both muscle lengths, and knee extension torques and VL muscle forces during stretch were similar across muscle lengths. This suggests either that neural inhibition was not present, that neural inhibition was similar between muscle lengths because of similar knee extension torques and muscle forces, or that surface EMG measurements are not sensitive enough to detect differences in neural inhibition. Although our data suggest that the in vitro muscle-length dependency of tFE is not relevant in vivo under maximum voluntary effort, we did not test at VL fascicle lengths much longer than optimal and so we cannot exclude this possibility based on our investigation. Testing at comparably long muscle lengths to in vitro studies was not possible here due to the constraints of the dynamometer.

In vitro (Edman et al. 1978; Lombardi and Piazzesi 1990) and in vivo (Dudley et al. 1990; Lee and Herzog 2002) studies have shown that tFE increases with increasing stretch magnitudes and stretch velocities. In our experiment, we found significantly greater VL fascicle stretch magnitudes and velocities at the long compared with the short muscle length. However, the greater mean VL fascicle stretch magnitude and velocity did not result in greater mean tFE at the long compared with the short muscle length. We also did not observe a significant positive correlation between tFE and fascicle stretch magnitude across muscle lengths, so we speculate that the difference in fascicle stretch magnitude across muscle lengths was not large enough to cause significantly greater tFE at the long compared with the short muscle length. The greater mean VL fascicle stretch velocity at the long muscle length likely did not affect the mean tFE across muscle lengths because the muscle fascicles were being stretched on the plateau region of their eccentric force–velocity relationship. Even though the observed tFE difference between short and long muscle lengths was not significant, the mean tFE at the long muscle length was greater than that at the short muscle length by ~ 4%. Further, tFE showed substantial variability (Fig. 3). Accordingly, we might be underpowered to detect a significant difference in tFE between lengths.

Residual force enhancement

We observed only small and non-significant rFE (1.3 ± 3.1%) at the short muscle length, but greater and significant rFE (10.6 ± 5.5%) at the long muscle length. Hence, rFE was muscle-length-dependent across the length range we tested here. Similar in vivo results from the knee extensors have previously been reported (Shim and Garner 2012). However, this is not consistent across all studies, as Power et al. (2013) found significant rFE in the knee extensors at short and long muscle lengths. The contrasting findings at the short muscle length might be due to the greater stretch amplitude (60° knee joint rotation) in the former study and/or participants acting closer to the plateau of their force–length relationship (60° target joint angle for the short muscle length) compared with our study. Similar to our findings though, Power et al. (2013) did observe greater rFE at the longer muscle length. Experiments on other lower limb extensors (plantar flexors) show similar muscle-length-dependent results for rFE on the ascending limb and plateau region of the force–length relationship. Findings from Pinniger and Cresswell (2007), Hahn et al. (2012), Hahn and Riedel (2018) and Fukutani et al. (2017) indicate that rFE of ~ 5–17% can be observed when stretches are applied at longer muscle lengths (i.e., at from ankle joint angles of − 5° to 20° dorsiflexion), whereas stretches over the same amplitude starting at a shorter muscle length (i.e., from − 15° to 0° dorsiflexion) do not result in significant rFE.

From an in vitro perspective, the differences in rFE at the short and long muscle lengths could be primarily attributed to non-crossbridge factors. This is because regarding the sarcomere length non-uniformity theory (Julian and Morgan 1979), (1) instabilities are only evident at long muscle lengths, but rFE has also been observed on the ascending limb and plateau region of the force–length relationship and (2) sarcomere length non-uniformities are not different during fixed-end contractions and the steady-state hold phase of stretch–hold contractions (Johnston et al. 2019). Besides cross-bridge mechanisms and sarcomere length non-uniformities, the latest research has found evidence supporting the idea that the engagement of a passive structural element (titin) can explain enhanced forces after active muscle stretch (Herzog et al. 2016; Shalabi et al. 2017; Herzog 2018). Our in vivo rFE results are supported by findings from Rassier and Herzog (2005), who observed an increase in titin stiffness with increasing muscle length. Therefore, stretches at longer muscle lengths could lead to greater rFE due to an increase in titin stiffness. Moreover, greater rFEs at longer muscle lengths are further supported by findings from Nocella et al. (2014) and Morgan et al. (2000), who showed that rFE was smaller or non-existent when stretch began on the ascending limb compared with the plateau region or descending limb of the force–length relationship.

From an in vivo perspective, predictions about mechanisms, such as titin engagement, during stretch and stretch–hold contractions become difficult because muscles act in series with long tendinous tissues within their MTU and are activated in concert with synergist and antagonist muscles. Regarding MTU compliance in vivo, Ichinose et al. (1997) reported that it decreases with increasing muscle length, where the stiffness of the MTU was estimated as the change in VL fascicle length over a given estimated change in patella tendon force. In our study, we only matched VL forces at two muscle lengths and we expected similar VL muscle fascicle stretch magnitudes across muscle lengths. As we found significantly more VL fascicle stretch during stretch–hold contractions at long compared with short lengths (Fig. 4), despite identical joint rotations, greater MTU compliance at short muscle lengths might be responsible. This is supported by our data as we found that preload forces account for 26% of the variance in VL fascicle stretch magnitudes across muscle lengths, with greater preloads increasing the amount of fascicle stretch, presumably by reducing MTU compliance and reducing the tendinous tissues’ ability to buffer active muscle lengthening during MTU lengthening (Konow and Roberts 2015). Thus, preload forces and forces during stretch should be considered in future studies that attempt to match muscle fascicle stretch amplitudes when assessing rFE at different muscle lengths in vivo.

Our finding of no rFE at the short muscle length could be influenced by four non-responders during the stretch–hold contractions (Fig. 3). The non-responder phenomenon was initially described by Oskouei and Herzog (2006) and has been confirmed by others (Hahn et al. 2007, 2012; Tilp et al. 2009). Two of the four non-responders in this study showed reduced VL fascicle stretch compared with the group mean and three of the non-responders showed lower muscle activity levels in the VL, RF or VM compared with the corresponding fixed-end contractions. However, all non-responders at short muscle lengths showed rFE at long muscle lengths, which suggests that reduced net knee extensor muscle activity and less VL fascicle stretch might explain why they were non-responders (i.e. no rFE) only at the short muscle length.

Residual force depression

Despite our motivation to investigate tFE and rFE during stretch and stretch–hold contractions with a maximum preload, our VL fascicle data show shortening–stretch and shortening–stretch–hold behaviours, respectively. rFE has been shown to be influenced in a dose-dependent manner by the amount of shortening preceding stretch (Lee et al. 2001) and active shortening is known to cause a long-lasting reduction in steady-state isometric force following shortening [i.e. residual force depression (Abbott and Aubert 1952; Granzier and Pollack 1989)], which can affect dorsiflexion force during fixed-end contractions (Raiteri and Hahn 2019). Consequently, we investigated fascicle behaviour during the initial phase of force development for each contraction condition. From six participants, we calculated fascicle shortening magnitudes and estimated fascicle shortening work over this period. We found no significant differences in either VL fascicle shortening magnitude or fascicle shortening work across contraction conditions at the same muscle length or across muscle lengths for the same contraction condition (Table 2). Therefore, potential shortening-induced residual force depression did not appear to confound our tFE and rFE findings across muscle lengths.

Relevance

Our in vivo results conflict with previous in vitro findings regarding the stretch-amplitude dependence of tFE. Although in vivo human studies have less potential to contribute to a detailed understanding of rFE-related mechanisms, from an applied perspective they can offer new insights into the ‘everyday’ physiological relevance of tFE and rFE during voluntary human movement (Seiberl et al. 2013; Paternoster et al. 2016). Eccentric muscle actions of the lower extremity are particularly important for absorbing kinetic energy during landing tasks and recently an increased contribution of the knee and hip joints to energy absorption during human hopping was shown following higher perturbation heights (Dick et al. 2019). Greater knee joint flexion following higher drops may increase the potential of tFE and rFE to help humans stabilise fall recovery following unexpected perturbations, as well as during expected drops (Hollville et al. 2019). Therefore, in vivo experiments investigating the mechanical factors that influence tFE and rFE are needed to better understand how these phenomena contribute to everyday muscle function and potentially enhance muscle performance and improve movement economy during energy-absorbing tasks.

Limitations

The approach we used to estimate VL muscle forces neglects changes in muscle shape, muscle architecture (e.g. pennation angle), and contributions from antagonistic muscles, such as the hamstrings, to the net joint torque. Hamstring muscle activity could not be recorded as participants were seated during the contractions. We also assumed fixed force contributions of the individual knee extensor muscles at the short and long muscle lengths based on literature-derived PCSAs, which are likely to vary between participants due to age, gender and their level of training experience. However, as tFE or rFE values were compared across muscle lengths from the same participant in this study and surface EMG revealed similar quadriceps muscle activities, we do not believe that these limitations would systematically bias our results.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether in vivo tFE and rFE differ at short and long muscle lengths with matched isometric VL force capacities following identical knee joint rotations. We found that tFE did not significantly differ between short and long muscle lengths, despite greater fascicle stretch at the longer muscle length (mean difference: 1.8 ± 2.0 mm), which suggests that tFE is either insensitive to this difference in stretch amplitude or that neural inhibition reduces the magnitude of the tFE at longer muscle lengths in vivo. We only observed rFE at the long, but not short, muscle length, which could be masked by lower preload forces at the short muscle length resulting in significantly less VL muscle fascicle stretch compared with the long muscle length. Thus, the difference in fascicle stretch (mean difference: 2.1 ± 2.1 mm) that we observed might contribute to our observation of rFE being muscle-length-dependent. Differences in the amount of VL fascicle shortening and work prior to fascicle stretch do not help to explain the differences in rFE we found between the short and long muscle lengths. Future studies that attempt to investigate how muscle length and stretch amplitude affect tFE and rFE in vivo should consider testing over a greater length range in a different muscle group (e.g. at lengths with and without substantial passive muscle force) and matching preload forces and forces during stretch [e.g. through a simple shear-wave tensiometer (Martin et al. 2018)], as well as assessing individual force contributions from synergist muscles to tFE and rFE during submaximal voluntary contractions [e.g. through supersonic shear-wave imaging (Bouillard et al. 2011)].

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- EMG:

-

Electromyography

- IMU:

-

Inertial measurement unit

- MTU:

-

Muscle–tendon unit

- MVC:

-

Maximal voluntary contraction

- PCSA:

-

Physiological cross-sectional area

- RF:

-

Rectus femoris

- rFE:

-

Residual force enhancement

- RMS:

-

Root-mean-square

- ROM:

-

Range of motion

- tFE:

-

Transient force enhancement

- VL:

-

Vastus lateralis

- VM:

-

Vastus medialis

References

Abbott BC, Aubert XM (1952) The force exerted by active striated muscle during and after change of length. J Physiol 117:77–86

Akima H, Kuno S-Y, Fukunaga T, Katsuta S (1995) Architectural properties and specific tension of human knee extensor and flexor muscles based on magnetic resonance imaging. Jpn J Phys Fit Sports Med 44:267–278. https://doi.org/10.7600/jspfsm1949.44.267

Arampatzis A, Karamanidis K, de Monte G et al (2004) Differences between measured and resultant joint moments during voluntary and artificially elicited isometric knee extension contractions. Clin Biomech 19:277–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2003.11.011

Babault N, Pousson M, Ballay Y, van Hoecke J (2001) Activation of human quadriceps femoris during isometric, concentric, and eccentric contractions. J Appl Physiol 91:2628–2634. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2001.91.6.2628

Bakenecker P, Raiteri B, Hahn D (2019) Patella tendon moment arm function considerations for human vastus lateralis force estimates. J Biomech 86:225–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2019.01.042

Bohm S, Marzilger R, Mersmann F et al (2018) Operating length and velocity of human vastus lateralis muscle during walking and running. Sci Rep 8:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23376-5

Bouillard K, Nordez A, Hug F (2011) Estimation of individual muscle force using elastography. PLoS ONE 6:e29261. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029261

Bullimore SR, Leonard TR, Rassier DE, Herzog W (2007) History-dependence of isometric muscle force: effect of prior stretch or shortening amplitude. J Biomech 40:1518–1524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.06.014

Cook CS, McDonagh MJ (1995) Force responses to controlled stretches of electrically stimulated human muscle-tendon complex. Exp Physiol 80:477–490. https://doi.org/10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003862

de Brito FH, de Campos D, Sakugawa RL (2018) Predictors of residual force enhancement in voluntary contractions of elbow flexors. J Sport Health Sci 7:318–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2018.06.001

Dick TJM, Punith LK, Sawicki GS (2019) Humans falling in holes: adaptations in lower-limb joint mechanics in response to a rapid change in substrate height during human hopping. J R Soc Interface 16:20190292. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2019.0292

Doguet V, Nosaka K, Guevel A et al (2017) Muscle length effect on corticospinal excitability during maximal concentric, isometric and eccentric contractions of the knee extensors. Exp Physiol 102:1513–1523. https://doi.org/10.1113/EP086480

Dudley GA, Harris RT, Duvoisin MR et al (1990) Effect of voluntary vs. artificial activation on the relationship of muscle torque to speed. J Appl Physiol 69:2215–2221. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1990.69.6.2215

Edman KA, Elzinga G, Noble MI (1978) Enhancement of mechanical performance by stretch during tetanic contractions of vertebrate skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol 281:139–155. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012413

Edman KA, Elzinga G, Noble MI (1982) Residual force enhancement after stretch of contracting frog single muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol 80:769–784. https://doi.org/10.1085/jgp.80.5.769

Edman KAP (1999) The force bearing capacity of frog muscle fibres during stretch: its relation to sarcomere length and fibre width. J Physiol 519:515–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0515m.x

Esteki A, Mansour JM (1996) An experimentally based nonlinear viscoelastic model of joint passive moment. J Biomech 29:443–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(95)00081-X

Farris DJ, Lichtwark GA (2016) UltraTrack: Software for semi-automated tracking of muscle fascicles in sequences of B-mode ultrasound images. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 128:111–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2016.02.016

Finni T, Ikegawa S, Lepola V, Komi PV (2003) Comparison of force-velocity relationships of vastus lateralis muscle in isokinetic and in stretch-shortening cycle exercises. Acta Physiol Scand 177:483–491. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01069.x

Flann KL, LaStayo PC, McClain DA et al (2011) Muscle damage and muscle remodeling: no pain, no gain? J Exp Biol 214:674–679. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.050112

Fukutani A, Misaki J, Isaka T (2017) Influence of joint angle on residual force enhancement in human plantar flexors. Front Physiol 8:234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00234

Gandevia SC (2001) Spinal and supraspinal factors in human muscle fatigue. Physiol Rev 81:1725–1789. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1725

Gillett JG, Barrett RS, Lichtwark GA (2013) Reliability and accuracy of an automated tracking algorithm to measure controlled passive and active muscle fascicle length changes from ultrasound. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng 16:678–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/10255842.2011.633516

Granzier HL, Burns DH, Pollack GH (1989) Sarcomere length dependence of the force-velocity relation in single frog muscle fibers. Biophys J 55:499–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82843-7

Granzier HL, Labeit S (2006) The giant muscle protein titin is an adjustable molecular spring. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 34:50–53. https://doi.org/10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003862

Granzier HL, Pollack GH (1989) Effect of active pre-shortening on isometric and isotonic performance of single frog muscle fibres. J Physiol 415:299–327. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017723

Hahn D (2018) Stretching the limits of maximal voluntary eccentric force production in vivo. J Sport Health Sci 7:275–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2018.05.003

Hahn D, Herzog W, Schwirtz A (2014) Interdependence of torque, joint angle, angular velocity and muscle action during human multi-joint leg extension. Eur J Appl Physiol 114:1691–1702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-014-2899-5

Hahn D, Hoffman BW, Carroll TJ, Cresswell AG (2012) Cortical and spinal excitability during and after lengthening contractions of the human plantar flexor muscles performed with maximal voluntary effort. PLoS ONE 7:e49907. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049907

Hahn D, Riedel TN (2018) Residual force enhancement contributes to increased performance during stretch-shortening cycles of human plantar flexor muscles in vivo. J Biomech 77:190–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2018.06.003

Hahn D, Seiberl W, Schmidt S et al (2010) Evidence of residual force enhancement for multi-joint leg extension. J Biomech 43:1503–1508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.01.041

Hahn D, Seiberl W, Schwirtz A (2007) Force enhancement during and following muscle stretch of maximal voluntarily activated human quadriceps femoris. Eur J Appl Physiol 100:701–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-007-0462-3

Harry JD, Ward AW, Heglund NC et al (1990) Cross-bridge cycling theories cannot explain high-speed lengthening behavior in frog muscle. Biophys J 57:201–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82523-6

Hermens HJ, Freriks B, Disselhorst-Klug C, Rau G (2000) Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 10:361–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1050-6411(00)00027-4

Herzog W (2018) The multiple roles of titin in muscle contraction and force production. Biophys Rev 10:1187–1199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12551-017-0395-y

Herzog W, Schappacher G, DuVall M et al (2016) Residual force enhancement following eccentric contractions: a new mechanism involving titin. Physiology 31:300–312. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiol.00049.2014

Hisey B, Leonard TR, Herzog W (2009) Does residual force enhancement increase with increasing stretch magnitudes? J Biomech 42:1488–1492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.03.046

Hollville E, Nordez A, Guilhem G et al (2019) Interactions between fascicles and tendinous tissues in gastrocnemius medialis and vastus lateralis during drop landing. Scand J Med Sci Sports 29:55–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13308

Huxley AF, Simmons RM (1971) Proposed mechanism of force generation in striated muscle. Nature 233:533–538. https://doi.org/10.1038/233533a0

Ichinose Y, Kawakami Y, Ito M, Fukunaga T (1997) Estimation of active force-length characteristics of human vastus lateralis muscle. Acta Anat 159:78–83. https://doi.org/10.1159/000147969

Jack A. Martin, Scott C. E. Brandon, Emily M. Keuler, James R. Hermus, Alexander C. Ehlers, Daniel J. Segalman, Matthew S. Allen, Darryl G. Thelen (2018) Gauging force by tapping tendons. Nature Communications 9(1)

Johnston K, Moo EK, Jinha A, Herzog W (2019) On sarcomere length stability during isometric contractions before and after active stretching. J Exp Biol 222:jeb209924. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.209924

Julian FJ, Morgan DL (1979) The effect on tension of non-uniform distribution of length changes applied to frog muscle fibres. J Physiol 293:379–392. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012895

Komi PV, Linnamo V, Silventoinen P, Sillanpaa M (2000) Force and EMG power spectrum during eccentric and concentric actions. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32:1757–1762. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200010000-00015

Konow N, Roberts TJ (2015) The series elastic shock absorber: tendon elasticity modulates energy dissipation by muscle during burst deceleration. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 282:20142800. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.2800

Lee H-D, Herzog W (2002) Force enhancement following muscle stretch of electrically stimulated and voluntarily activated human adductor pollicis. J Physiol 545:321–330. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2002.018010

Lee HD, Herzog W, Leonard T (2001) Effects of cyclic changes in muscle length on force production in in-situ cat soleus. J Biomech 34:979–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00077-X

Leonard TR, DuVall M, Herzog W (2010) Force enhancement following stretch in a single sarcomere. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299:C1398–C1401. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00222.2010

Leys C, Ley C, Klein O et al (2013) Detecting outliers: do not use standard deviation around the mean, use absolute deviation around the median. J Exp Soc Psychol 49:764–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.03.013

Lieber RL, Leonard ME, Brown-Maupin CG (2000) Effects of muscle contraction on the load-strain properties of frog aponeurosis and tendon. Cells Tissues Organs 166:48–54. https://doi.org/10.1159/000016708

Linari M, Bottinelli R, Pellegrino MA et al (2004) The mechanism of the force response to stretch in human skinned muscle fibres with different myosin isoforms. J Physiol 554:335–352. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2003.051748

Linnamo V, Strojnik V, Komi PV (2006) Maximal force during eccentric and isometric actions at different elbow angles. Eur J Appl Physiol 96:672–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-005-0129-x

Lombardi V, Piazzesi G (1990) The contractile response during steady lengthening of stimulated frog muscle fibres. J Physiol 431:141–171. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018324

Maganaris CN, Baltzopoulos V, Sargeant AJ (2002) Repeated contractions alter the geometry of human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 93:2089–2094. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00604.2002

Morgan DL (1990) New insights into the behavior of muscle during active lengthening. Biophys J 57:209–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82524-8

Morgan DL, Whitehead NP, Wise AK et al (2000) Tension changes in the cat soleus muscle following slow stretch or shortening of the contracting muscle. J Physiol 522:503–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00503.x

Nocella M, Cecchi G, Bagni MA, Colombini B (2014) Force enhancement after stretch in mammalian muscle fiber: no evidence of cross-bridge involvement. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 307:C1123–C1129. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00290.2014

Oskouei AE, Herzog W (2006) The dependence of force enhancement on activation in human adductor pollicis. Eur J Appl Physiol 98:22–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-006-0170-4

Paternoster FK, Seiberl W, Hahn D, Schwirtz A (2016) Residual force enhancement during multi-joint leg extensions at joint- angle configurations close to natural human motion. J Biomech 49:773–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.02.015

Pinnell RAM, Parastoo M, Mazara N, Weersink E, Brown SHM, Power GA (2019) Residual force enhancement and force depression in human single muscle fibers. J Biomech 91:164–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2019.05.025

Pinniger GJ, Cresswell AG (2007) Residual force enhancement after lengthening is present during submaximal plantar flexion and dorsiflexion actions in humans. J Appl Physiol 102:18–25. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00565.2006

Power GA, Makrakos DP, Rice CL, Vandervoort AA (2013) Enhanced force production in old age is not a far stretch: an investigation of residual force enhancement and muscle architecture. Physiol Reps 1:e00004. https://doi.org/10.1002/phy2.4

Raiteri BJ, Hahn D (2019) A reduction in compliance or activation level reduces residual force depression in human tibialis anterior. Acta Physiol 225:e13198. https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.13198

Rassier DE, Herzog W (2005) Relationship between force and stiffness in muscle fibers after stretch. J Appl Physiol 99:1769–1775. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00010.2005

Ruttiman RJ, Sleboda DA, Roberts TJ (2019) Release of fascial compartment boundaries reduces muscle force output. J Appl Physiol 126:593–598. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00330.2018

Scott SH, Brown IE, Loeb GE (1996) Mechanics of feline soleus: I. Effect of fascicle length and velocity on force output. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 17:207–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00124243

Seiberl W, Paternoster F, Achatz F et al (2013) On the relevance of residual force enhancement for everyday human movement. J Biomech 46:1996–2001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.06.014

Shalabi N, Cornachione A, de Souza LF et al (2017) Residual force enhancement is regulated by titin in skeletal and cardiac myofibrils. J Physiol 595:2085–2098. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP272983

Sharifnezhad A, Marzilger R, Arampatzis A (2014) Effects of load magnitude, muscle length and velocity during eccentric chronic loading on the longitudinal growth of the vastus lateralis muscle. J Exp Biol 217:2726–2733. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.100370

Shim J, Garner B (2012) Residual force enhancement during voluntary contractions of knee extensors and flexors at short and long muscle lengths. J Biomech 45:913–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.01.026

Tilp M, Steib S, Herzog W (2009) Force-time history effects in voluntary contractions of human tibialis anterior. Eur J Appl Physiol 106:159–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-009-1006-9

Webber S, Kriellaars D (1997) Neuromuscular factors contributing to in vivo eccentric moment generation. J Appl Physiol 83:40–45. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1997.83.1.40

Westing SH, Seger JY, Karlson E, Ekblom B (1988) Eccentric and concentric torque-velocity characteristics of the quadriceps femoris in man. Eur J Appl Physiol 58:100–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00636611

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PB contributed to conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript; BR contributed to conception and design of the study, data analysis and interpretation and revising the manuscript critically; DH contributed to conception and design of the study, data interpretation and revising the manuscript critically; all authors gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Olivier Seynnes.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bakenecker, P., Raiteri, B.J. & Hahn, D. Force enhancement in the human vastus lateralis is muscle-length-dependent following stretch but not during stretch. Eur J Appl Physiol 120, 2597–2610 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-020-04488-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-020-04488-1