Abstract

Objective

The aim of this review is to evaluate associations between possible late effects of cancer treatment (i.e. physical complaints, fatigue, or cognitive complaints) and work ability among workers beyond 2 years after cancer diagnosis who returned to work. The role of job resources (social support, autonomy, leadership style, coaching, and organizational culture) is also evaluated.

Methods

The search for studies was conducted in PsycINFO, Medline, Business Source Premier, ABI/Inform, CINAHL, Cochrane Library and Web of Science. A quality assessment was used to clarify the quality across studies.

Results

The searches included 2303 records. Finally, 36 studies were included. Work ability seemed to decline shortly after cancer treatment and recover in the first 2 years after diagnosis, although it might still be lower than among healthy workers. No data were available on the course of work ability beyond the first 2 years. Late physical complaints, fatigue and cognitive complaints were negatively related with work ability across all relevant studies. Furthermore, social support and autonomy were associated with higher work ability, but no data were available on a possible buffering effect of these job resources on the relationship between late effects and work ability. As far as reported, most research was carried out among salaried workers.

Conclusion

It is unknown if late effects of cancer treatment diminish work ability beyond two years after being diagnosed with cancer. Therefore, more longitudinal research into the associations between possible late effects of cancer treatment and work ability needs to be carried out. Moreover, research is needed on the buffering effect of job resources, both for salaried and self-employed workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A growing number of people in the workforce have experienced a cancer diagnosis at some time during their life. The majority of working people diagnosed with cancer re-enter the workplace. The mean rates of return to work reported in reviews are 62% (Spelten et al. 2002), 64% (Mehnert 2011), and 73% (De Boer et al. 2020a). Return to work pathways vary, among others because of differences in reintegration strategies between countries (Kiasuwa Mbengi et al. 2018), the availability of disability pension (Tikka et al. 2017), or the effectiveness of programs to support return to work (Boer et al., 2015).

Compared to healthy people 1.4 times more unemployment is observed among cancer patients (De Boer et al. 2009). However, the group of workers with a cancer diagnosis in their life history will continue to expand as survival rates are greatly improving, as the incidence of cancer is expected to rise a further 75% over the next two decades (World Health Organization 2012; Stewart and Wild 2014) and as the retirement age is expected to be raised even further in many countries. As studies concerning cancer and work merely focus on the first two years after diagnosis and often concern whether people return to work, less is known about the population after return to work beyond these first two years. As a consequence, it is important to focus on the occupational well-being and the situation in the workplace of this group of workers after they returned to work.

A range of long-term physical and psychological changes can be experienced by cancer survivors (Ganz 2001). These changes may present during active treatment and persist on the long term, beyond the first two years after cancer diagnosis, or changes may appear months or years later as late effects (Stein et al. 2008). As a clear distinction between long-term and late effects is not always possible, in this review all these long-term changes that affect daily functioning are indicated as late effects in line with the definition of the Dutch Federation of Cancer Patient Organizations (Dutch Federation of Cancer Patient Organizations NFK 2017). Late effects of cancer treatment include, for instance, fatigue (Prue et al. 2006; Servaes et al. 2007; Reinertsen et al. 2010), lymphedema (Cormier et al. 2010), cardiovascular disease (Keating et al. 2006; Drafts et al. 2013), osteoporosis (Miller et al. 2016), anxiety (Mitchell et al. 2013), fear of recurrence (Lebel et al. 2016), or cognitive complaints (e.g. problems with concentration, learning and memory) (Wefel et al. 2015). Late effects of cancer treatment may continue to influence the ability to function at work for as long as ten or even more years after diagnosis (Koppelmans et al. 2012; Silver et al. 2013). The Dutch Federation for Cancer Patient Organizations reported that impairments resulting from these late effects were experienced in particular also in the context of work (Dutch Federation of Cancer Patient Organizations NFK 2017). This underlines the importance of studying late effects in the context of work.

To make comparisons possible it is necessary to study the associations of late effects of cancer treatment with a work outcome measure also used in studies among the general population or populations with chronic diseases. Therefore, a useful concept is ‘work ability’, which generally refers to the extent to which someone is able to carry out their work, taking the demands of the job, and health and mental resources into account (Ilmarinen et al. 2005). Work ability is reported to be a predictor of other work outcome measures among healthy populations, like absenteeism or early retirement (Ilmarinen and Tuomi 2004). In general, different (chronic) health problems are reported to be associated with decreased work ability (Leijten et al. 2014), and predictors of work ability are similar for workers with and without chronic health conditions (Koolhaas et al. 2013). However, other definitions are also used in the scientific literature (Lederer et al. 2014) and measurement methods of work ability may vary between studies (Brady et al. 2019; Cadiz et al. 2019). About a decade ago in an overview by Munir, Yarker, and McDermott (2009) on work ability and cancer, it was reported that very few well-validated measures of work ability had been used in previous studies. Therefore, it is important to report about the way work ability was assessed in the included studies within the current systematic literature review as well.

Furthermore, it is important to determine whether specific supporting factors in achieving work goals, so-called job resources within the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al. 2001), demonstrate an association with work ability in this specific population workers past cancer diagnosis or if job resources can even buffer a possible negative association of late effects of cancer treatment with a lower work ability. In the JD-R model, job demands are regarded as the aspects of the job that require effort and it is possible that the late effects of cancer treatment result in work demands being experienced as heavier. Furthermore, across studies among general populations job resources are positively related to work ability (Brady et al. 2019). In addition, in some studies job resources were reported to buffer the impact of job demands on burn-out (Bakker et al. 2005; Xanthopoulou et al. 2007). Clearly, job resources in the current work situation might be of great importance for work functioning among workers experiencing any late effects of cancer treatment after they returned to work.

As there is a shift in labor markets towards more flexible contracts, and smaller enterprises, the subpopulation of self-employed, freelancers and entrepreneurs, in other words the non-salaried, grows in several European Union member states (CBS 2019). These workers show different behavior after a cancer diagnosis than the salaried (Torp et al. 2018), as they more often continue working during treatment and take fewer time off work due to cancer. This might be due to the financial necessity to earn an income. Another difference is that the non-salaried have neither an employer, a supervisor, a human resource manager, an occupational physician, nor colleagues to provide job resources such as social support.

In short, this systematic literature review will focus on the work ability of all people working after a cancer diagnosis and cancer treatment (salaried and non-salaried). The aim is to present an overview of the studies that present data on work ability, also reporting on the method used to assess work ability. Furthermore, any available results on a possible association of late effects (physical complaints, fatigue or cognitive complaints) and work ability beyond the first 2 years after diagnosis will be reviewed. Finally, the role of job resources will also be evaluated.

Methods

Search strategy

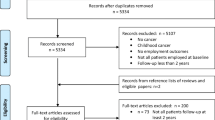

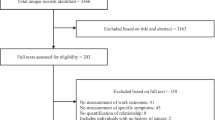

To structure this systematic literature review the checklist of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was used (Moher et al. 2009). Systematic searches for publications were conducted on March 10th, 2020 in the databases PsycINFO, Medline, Business Source Premier and CINAHL, and on March 13th, 2020 in the databases ABI/Inform, Cochrane Library and Web of Science. Search terms were determined by the first author and an information specialist in mutual agreement with the other authors. In general, the search consisted of search terms for cancer combined with search terms for paid work. Search terms were broad to ensure no relevant studies would be missed. No restrictions were placed on publication date. For full search strategies, see Appendix 1. Additional searches consisted of citation tracking by the first author to discover articles not found by the systematic search.

Inclusion criteria: considered studies had to (1) be published in English peer-reviewed journals, (2) be an original quantitative research article (including pilot studies), (3) focus on work ability in people working after a cancer diagnosis, and (4) include adults (18 years or older).

Exclusion criteria: articles were excluded if they focused on (1) work-related risk factors for cancer, or (2) the ability to work if regarded as the ability to be at work rather than in the sense of work ability during work, or (3) populations entirely without paid work, or (4) populations entirely on long term sick leave, or (5) predicting return to work by work ability, or (6) the assessment of the effect of an intervention regarding return to work after a cancer diagnosis.

Study selection

First, after the removal of duplicates, the search results were screened by title and abstract in Rayyan (Ouzzani et al. 2016) independently by the first author and two other researchers (the second author and research trainees). Those papers clearly not relevant to this review were eliminated. In case of a missing abstract or missing relevant details needed for screening, full paper copies were retrieved and screened. Second, the then included papers were used for additional citation tracking by the first author to identify possible additional studies. Third, the three authors discussed the eligibility of the remaining papers based on the criteria for inclusion and exclusion.

Data extraction

After this, the first author extracted a range of data from the included papers relevant for this review, including data on (1) study design, (2) population (e.g. number of participants included in analyses, age, gender, cancer type, time since cancer diagnosis), (3) setting, (4) the assessment method of work ability, (5) possible late effects of cancer treatment, namely physical complaints, fatigue, and cognitive complaints, and (6) possible job resources (leadership style, coaching, organizational culture, social support, and autonomy). This data-extraction was reviewed by the second and the third author.

Study characteristics

The searches included 2303 records, including two results by additional citation tracking. After the removal of duplicates, 1565 titles and abstracts were screened. After elimination of the studies clearly not relevant to this review and after close reading 36 studies remained. A reason for this decrease in numbers was that studies on cancer and work mostly concern whether people return to work during the first 2 years after diagnosis and that these studies also focus on many other work-related aspects other than work ability. The study selection is documented in a PRISMA flow diagram, see Fig. 1. The data-extraction of the 36 studies is presented in Table 1.

The 36 studies covered 12 (33%) longitudinal studies (De Boer et al. 2008; Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2009; Bains et al. 2012; Nilsson et al. 2016; Doll et al. 2016; Zanville et al. 2016; Duijts et al. 2017; Hartung et al. 2018; Wolvers et al. 2019; Gregorowitsch et al. 2019; Tamminga et al. 2019; Couwenberg et al. 2020), six (17%) case–control studies (Taskila et al. 2007; Gudbergsson et al. 2008a, 2011; Lee et al. 2008; Lindbohm et al. 2012; Carlsen et al. 2013), and 18 (50%) cross-sectional studies. Almost half of all included studies was published in 2017 or later. The setting of 14 studies was Northern Europe. Other European settings were the Netherlands (eight studies), and the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, and Slovakia with one study each. Other settings outside Europe were the United States of America (five studies), Brazil (one study), and Asia (three studies). The studies focused on a combination of types of cancer in 16 studies, breast cancer in ten studies, prostate cancer in three studies, and ovarian, rectal, colorectal, thyroid, stomach cancer, hematological cancer and lymphoma in one study each. Gender was not mentioned in five studies (14%) among populations with a past breast cancer diagnosis, very likely to be women but possibly not all, and not in two studies among prostate cancer diagnoses, the latter certainly concerning men. The gender distribution therefore showed eight studies (22%) among women, five (14%) not with full certainty only among women, three studies (8%) among men, and 20 studies (56%) among both genders. Type of employment was not clear in 16 studies (44%). The other 20 studies concerned 13 studies (36%) with both employed and self-employed, 7 studies with employed only (20%), and none of the studies only included self-employed. The baseline of the data collection varied from the moment of diagnosis, the first day of sick leave, to the end of primary treatments.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using three quality assessment checklists. For cohort and case–control studies the checklists from the ‘Critical Appraisal Skills Program’ (CASP) were used (Critical Appraisal Skills Program 2018a, b). Some items were adapted to the current study. These adjustments are described in the notes below the Tables 2, 3, and 4. For cross-sectional studies (except case–control studies) the Appraisal tool for Cross Sectional Studies (AXIS tool) (Downes et al.) was used. The quality assessment was used to test the quality across studies.

The quality assessment was performed for all 36 studies by the first author. The second and the third author independently assessed the quality of different subsets of cohort, case–control and cross-sectional studies. The results were discussed afterwards, and agreement was reached on the level of quality of each of the included studies for the present study.

The 12 cohort studies were all of good quality and therefore no studies were excluded. Of the 12 included cohort studies two studies made use of a follow up period long enough to possibly investigate late effects of cancer treatment that is beyond two years after diagnosis (Duijts et al. 2017; Gregorowitsch et al. 2019). Furthermore, these two studies concerned European populations.

Also the six case–control studies were all of good quality, not resulting in any exclusions. The time since diagnosis was beyond 2 year after diagnosis in four studies and two studies also included participants within the first two years after diagnosis. Five studies of the case–control studies concerned European populations (Taskila et al. 2007; Berg Gudbergsson et al. 2008a, b; Gudbergsson et al. 2011; Lindbohm et al. 2012; Carlsen et al. 2013).

The 18 cross-sectional studies showed some quality differences, but the quality of all studies was acceptable. The selection process in two pilot studies might have impaired representativeness (Neudeck et al. 2017; Bielik et al. 2020). In one cross-sectional study the time since diagnosis was not clear (Ortega et al. 2018), but the other 17 cross-sectional studies concerned populations with participants beyond 2 years after diagnosis. For the checklists see Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Assessment methods used to measure work ability

Six (17%) of the included studies (Von Ah et al. 2017, 2018; Ho et al. 2018; Hartung et al. 2018; Gregorowitsch et al. 2019; Couwenberg et al. 2020) used the complete Work Ability Index (WAI), a questionnaire that consists of seven items. These 7 items are (1) current work ability compared with the lifetime-best (on a scale of 0–10), (2) work ability in relation to the (physical and mental) demands of the job, (3) number of current diseases diagnosed by a physician, (4) estimated work impairment due to diseases, (5) sick leave during the past 12 months, (6) own prognosis of work ability two years from now, and (7) mental resources. Only partial use of the WAI (one or more items) was made by 22 (61%) studies, with the first WAI item being used in 21 studies (see Table 1).

Of the eight (22%) studies not using the complete or partial WAI, different ways to assess work ability were used, namely (1) the Functional Well-Being subscale of the FACT/GOG-Ntx (version 4) (Zanville et al. 2016), (2) a multiple-choice question regarding lessened work-related ability (Lee et al. 2008), (3) a self-reported reduction of work ability (Fosså and Dahl 2015; Musti et al. 2018), (4) a multiple choice question regarding being unable to work full time, unable to work the same as before cancer or unable to work at all (Moskowitz et al. 2014), (5) the Work Limitations Questionnaire (the percentage of time limited in performing work tasks in the last two weeks) (Ortega et al. 2018), (6) a question on current work ability in combination with other information (Bielik et al. 2020), and (7) a non-validated ad hoc questionnaire (Neudeck et al. 2017). In brief, 22% of the studies did not use the complete or partial WAI but other ways to assess work ability.

Results: work ability in working people with a past cancer diagnosis

After a cancer diagnosis the level of work ability tended to be experienced as lower than before diagnosis. However, cohort studies demonstrated that the level of work ability among workers during the first two years past cancer diagnosis appeared to improve significantly (De Boer et al. 2008; Nilsson et al. 2016). One longitudinal study with a two year follow up reported work ability improved over time most prominently from baseline to 1 year of follow-up and thereafter remained stable up to 2 years of follow-up (Tamminga et al. 2019). However, other longitudinal studies that focused on the first two years did not have data on the course of work ability (Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2009; Bains et al. 2012; Doll et al. 2016; Zanville et al. 2016), nor had the study with a follow-period of four years past cancer diagnosis (Duijts et al. 2017). However, compared to controls work ability was reported to be significantly lower when 2 years after diagnosis (Couwenberg et al. 2020).

Cross-sectional studies that used data reported by the respondents retrospectively with regard to different time points after cancer diagnosis, also reported that work ability was lowered after cancer diagnosis and experienced as increasing again (Kiserud et al. 2016; Cheung et al. 2017; Musti et al. 2018; Bielik et al. 2020). Some studies only focused on the association of different types of treatment and work ability (Ortega et al. 2018; Dahl et al. 2020). Furthermore, when the complete Work Ability Index (WAI) was used to assess work ability the results were as follows. Suboptimal work ability was reported in 26% and 37% of cases (Von Ah et al. 2017; Ho et al. 2018) and among a population with a prostate cancer diagnosis in the previous 0–23 years (mean 4 years) and partially at work, 10% or 22% reported a reduction of their work ability (Fosså and Dahl 2015). As the studies made use of different ways to assess work ability at various moments after diagnosis and also included different types of cancer, case–control studies offer a possibility to make comparisons between workers with and workers without a past cancer diagnosis. Six studies made use of a reference group or a norm group, mostly beyond the first two years after diagnosis of which five studies found that work ability was lower in workers with a past cancer diagnosis, than in workers without such a diagnosis (Gudbergsson et al. 2008a, 2011; Lee et al. 2008; Lindbohm et al. 2012; Carlsen et al. 2013). Only one study, using a sample 2–6 years after different types of cancer diagnosis, did not report any differences (Taskila et al. 2007). These results demonstrate that work ability tends to be lower among cancer survivors than among samples without a past cancer diagnosis also on the long term. In summary, a number of the cross-sectional and case–control studies showed that workers more than 2 years past cancer diagnoses experience a lower level of work ability than before the cancer diagnosis.

An important finding was that a lower work ability at baseline was one of the strongest predictors of poorer follow-up work ability at 6 months after treatment among a sample with colorectal cancer in one of the longitudinal studies (Bains et al. 2012). Also in a cross-sectional study among a sample 1–16 years after breast cancer diagnosis, the retrospectively self-reported work ability during treatment, as well as that before diagnosis, was associated with current work ability (Cheung et al. 2017). Moreover, in a cross-sectional study 2–6 years after primary treatment of breast, testicular or prostate cancer, mental work ability (and not physical work ability) correlated with lower current work ability (Gudbergsson et al. 2008b). Another finding is that a higher current work ability is associated with work continuation one year later (Duijts et al. 2017).

Furthermore, self-employment among cancer survivors appeared to be a predictor for lower work ability (Torp et al. 2012). Moreover, the negative effect of self-employment on work ability among cancer survivors was reported to be mediated by reduced working hours and a negative cancer-related financial change (Torp et al. 2017). All in all, self-employed, without employees (freelancers) or with employees (entrepreneurs), were not a prominent focus in the included studies. The few available results among the non-salaried show a lower work ability and the importance of negative changes in the financial situation.

Gender differences in work ability among cancer survivors were also reported, but it is difficult to present an overview of possible gender differences with regard to work ability, as factors like type of cancer (and connected gender and age differences) and differences in physical and mental work ability cloud the issue. For instance, breast cancer, testicular cancer and prostate cancer have different profiles with regard to gender and age. Men had a higher current work ability (8.4, SD 1.8) than women (8.0, SD 2.1), p < 0.04, effect size = 0.20, while no gender differences were reported for current work ability in the group of matched controls without a past cancer diagnosis (8.6, SD 1.6) (Gudbergsson et al. 2011). Furthermore, female survivors had lower mental work ability than controls (effect size 0.30, p < 0.001) but no lower physical work ability, while male survivors had lower physical work ability (effect size 0.37, p < 0.001) and also lower mental work ability (effect size 0.27, p = 0.004) than male controls (Gudbergsson et al. 2011). In a study among workers 15–39 months after a diagnosis with one of various types of the most common cancer types high current work ability was reported for men (8.6, SD 1.8), as well as for women (8.6, SD 1.7) (Torp et al. 2012). Taskila et al. (2007) reported the highest mean current work ability for testicular cancer (9.0) and the lowest for prostate cancer (8.0), in a study which also covered breast cancer and lymphoma. Furthermore, in another study no difference in work ability between men with testicular cancer diagnosis (8.8) and controls (8.7) was reported, while prostate cancer survivors had a lower work ability (8.3) than controls (p < 0.01) (Lindbohm et al. 2012).

Results: late effects of cancer treatment and work ability

Physical complaints and work ability

Eight (22%) of the included studies analyzed a possible association between late physical complaints and work ability. One study had a case–control design (Gudbergsson et al. 2011), and the other studies were cross-sectional (Gudbergsson et al. 2008b; Moskowitz et al. 2014; Fosså and Dahl 2015; Dahl et al. 2016, 2019; Torp et al. 2017; Ho et al. 2018). In the studies physical impairments or the experienced limitations were associated with lower work ability or were seen more frequently in cases of suboptimal work ability beyond 2 years after diagnosis. In short, physical complaints after cancer treatment continue to show associations with lower work ability beyond the first two years after cancer diagnosis.

Fatigue and work ability

Four (11%) of the included studies analyzed a possible association between late fatigue and work ability. Carlsen et al. (2013), used the first WAI item in a case–control study design, and reported that fatigue was associated with reduced current work ability 5–8 years after a breast cancer diagnosis, and that this association was stronger among cancer survivors (OR 10.7, CI 3.31–34.3) than among the controls (OR 4.11, CI 1.97–8.57), suggesting moderation. The other three studies were cross-sectional. In one of these studies the complete WAI to assess work ability was used, and general, physical, and mental fatigue were reported to be less common in breast cancer survivors with optimal work ability. A higher level of physical fatigue was significantly associated with poorer work ability (Ho et al. 2018). Another cross-sectional study used the first item of the WAI to assess work ability and reported that those with low work ability had significantly higher mean levels of total fatigue (Dahl et al. 2019). Another cross-sectional study did not report a significant association of fatigue with work ability, however fatigue was part of more comprehensive constructs, making specific inferences difficult. Furthermore, in this study work ability was assessed by a multiple choice question regarding being unable to work full time, unable to work the same as before cancer or unable to work at all (Moskowitz et al. 2014) To summarize, the scarce data demonstrate that fatigue can be associated with lower work ability among workers with a past cancer diagnosis.

Cognitive complaints and work ability

Four (11%) of the included studies analyzed a possible association between late cognitive complaints and work ability. The study designs were all cross-sectional. In this systematic literature review attentional fatigue, i.e. experiencing lower levels of attention, is regarded as a cognitive complaint. A significant relationship (β = 0.627, p < 0.001) between higher levels of attention and perceived work ability assessed by the complete WAI, was reported by Von Ah et al. (Von Ah et al. 2017). Attentional fatigue explained 40% of the variance in perceived work ability among 68 breast cancer survivors on average 5 years after diagnosis. Von Ah et al. (2018) also reported that cognitive impairment was associated with poorer work ability (β = − 0.66, p < 0.000) and that perceived cognitive ability was significantly related to higher levels of work ability (β = 0.47, p < 0.000). Furthermore, Ho et al. (2018) reported breast cancer survivors (3–8 years after diagnosis) to have lower scores for cognitive functioning in case of suboptimal work ability. Another study, by Moskowitz et al. (2014), also included cognitive symptoms, but as part of more comprehensive constructs, making specific inferences difficult. So, although results are scarce, recent studies indicate that cognitive complaints can be associated with low work ability among working cancer survivors.

Results: current job resources and work ability

As has already been stated, job resources can be of importance for work functioning, also among workers who returned to work after cancer treatment and experiencing any late effects of cancer treatments. Job resources can among others be provided by (1) social support, (2) autonomy, (3) leadership style, (4) coaching, or (5) organizational culture (Demerouti et al. 2001). Of these job resources the current experienced level and their possible association with work ability was taken into consideration in nine (25%) of the included studies; three case–control studies and six cross-sectional studies.

Social support by colleagues was reported to be associated with positive outcomes with regard to higher work ability in case–control studies (Taskila et al. 2007; Lindbohm et al. 2012; Carlsen et al. 2013), as well in cross-sectional studies (Gudbergsson et al. 2008b; Torp et al. 2012; Musti et al. 2018). For instance, a high level of cancer-related support by colleagues was associated with higher work ability 15–39 months after diagnosis, also in multivariate regression (Torp et al. 2012). Social support by supervisors was reported to be associated with positive outcomes with regard to higher work ability as well in case–control studies (Lindbohm et al. 2012; Carlsen et al. 2013), as in cross-sectional studies (Torp et al. 2012; Musti et al. 2018). For instance, less help and support from a supervisor was significantly associated with reduced work ability among workers 5–8 years after breast cancer diagnosis (Carlsen et al. 2013).

Three cross-sectional studies analyzed a possible association of autonomy at work with work ability, although the construct of autonomy was defined somewhat differently. In two of these studies the respondents reported the ‘decision latitude’ (opportunities to learn new things at work and decide how to carry out the work tasks) at the time of the cancer diagnosis (Torp et al. 2012, 2017). Decision latitude was found to be significantly related with work ability among a sample workers who returned to work after various cancer diagnoses, 6% of whom were self-employed (Torp et al. 2012). In addition, it was also reported that the self-employed experienced a higher decision latitude, preventing low work ability (Torp et al. 2017). Furthermore, Cheung, Ching, Chan, Cheung, and Cheung (2017) reported ‘control’, a related concept, to be correlated with work ability (Rs = 0.29, p = 0.04).

Leadership style, coaching and organizational culture were assessed in almost none of the included studies. However, social climate at work, a concept related to organizational culture (Ehrhart and Schneider 2016), was assessed in two studies (Taskila et al. 2007; Lindbohm et al. 2012), with only one study analyzing a possible association with work ability. This study showed that a better social climate at work was related to a higher mental work ability (Taskila et al. 2007). The only behavior of supervisors related to leadership style that was assessed in some of the studies was social support from supervisors and their avoidance behavior. Worth noting is that male workers with a cancer diagnosis experienced lower work ability as a result of supervisors’ avoidance behavior (p < 0.001), while female workers with a cancer diagnosis in their past experienced lower work ability if avoidance behavior of colleagues was higher (p < 0.001) (Lindbohm et al. 2012).

All in all, the attention paid to job resources among the included studies was limited. Nevertheless, the scarce results indicate a positive association between job resources and work ability, although no data on job resources that affect the strength of the association of the late effects with work ability have been found.

Discussion

As high numbers of working people diagnosed with cancer re-enter the workplace and the group of workers with a cancer diagnosis in their life history will continue to expand, it is important to have an overview over the current state of knowledge about the course of work ability after diagnosis, and about the associations between late effects of cancer treatment and work ability. Knowledge about the role of job resources (social support, autonomy, leadership style, coaching, and organizational culture) in this is also relevant.

The searches included 2303 records in total, and 36 studies were selected. A quality assessment was used to clarify the quality across studies and we found that most research was cross-sectional (50%). These studies and the six case–control studies were mostly completely or in part focused on workers beyond two years past cancer diagnosis. However, only two of the 12 cohort studies had a follow-up beyond 2 years after diagnosis.

It is an important finding that studies with various study populations and study designs demonstrate that work ability seems to be lowered shortly after the start of cancer treatment and tends to recover during the first two years after the diagnosis, although work ability might still be lower than in healthy populations. Because there is a lack of longitudinal data beyond the first two years after diagnoses, the further course of work ability is not clear. Differences in the level of work ability between workers with different types of cancer diagnosis in the past are reported. Late physical complaints, fatigue or cognitive complaints are associated with lower work ability across all relevant studies. None of these studies had a longitudinal design.

Social support and characteristics of autonomy were assessed in some of the studies, indicating that these current job resources are associated with higher work ability, in line with results in the healthy population (Gould et al. 2000) and also in populations experiencing chronic health problems (Leijten et al. 2014). No data were available on the possible buffering effects of social support and autonomy on the relationship between late effects of cancer treatments and work ability. Organizational culture in general was not investigated, only social climate at work in one study, which was positively related to a higher work ability. No results were found for leadership style, and coaching. In short, research on late effects of cancer treatment and work ability among workers past cancer diagnosis has not yet been enriched or combined with investigations of possible buffering by job resources.

Limitations

First, of the 36 studies included, ten studies (28%) solely concerned workers with a breast cancer diagnosis, which may have caused bias. The other studies used in this review included considerable variations in type(s) of cancer and cancer treatments. However, the impact of differences in diagnosis is not clear. For instance, survivors of testicular cancer reported the highest work ability (even comparable to controls), survivors with prostate cancer the lowest level, and the breast cancer population in between (Taskila et al. 2007; Lindbohm et al. 2012). It is important to be aware of the very different profiles with regard to gender and age of these types of cancer. Among healthy populations age is generally associated with work ability, younger workers usually estimating their work ability at a higher level (Gould et al. 2000; Berg van de et al. 2010; Bender et al. 2015). Also, variation among participants in the disease status may cause a lack of comparability, as there are differences between studies with regard to including participants with recurrence, or distant metastasis, while awareness of disease progression or the possibility of the cancer not being curable, might influence perceived work ability.

Second, the way that work ability was measured did not seem to influence the results. The complete WAI (Work Ability Index) was used in a few studies only, while the vast majority of studies used only one or more of the items adopted from the WAI, with the first item (current work ability compared to life-time best) being used most frequently. The complete WAI is reported to be a very predictive and cross-nationally stable instrument (Radkiewicz and Widerszal-Bazyl 2005) to predict work disability, retirement and mortality in a reliable way (Ilmarinen and Tuomi 2004). Furthermore, the first item of the WAI is reported to have a very strong association with the complete WAI (Ahlstrom et al. 2010), and to show similar strong predictive value for the degree of sick leave, health-related quality of life (Ahlstrom et al. 2010) and future disability (Alavinia et al. 2009). Although in the general populations the use of the complete WAI might result in a higher probability of lower work ability in women compared to using only the first item of the WAI (El Fassi et al. 2013), using only one item of the WAI is regarded as a good alternative for the complete WAI. A minority of the included studies did not use any of the WAI items, but used different surveys, ad hoc questions, a perception of the participant, etcetera. In short, when interpreting results on work ability in workers with a past cancer diagnosis, conscientiousness in reviewing the assessment tool of work ability is wise, although the results across the studies included in this review do not lead to different conclusions.

Third, the late effects of cancer treatment evaluated in this systematic literature review were not all possible prevalent late effects. For instance, depression was not included, and the effect of co-morbidities was not clear. However, the scarce studies that investigated a possible association of late physical complaints, fatigue and cognitive complaints with work ability, indicated that these complaints after cancer treatment were associated with lower work ability in almost all included studies. It is important to be alert of the likelihood of stronger associations of specific complaints with work ability in the cancer population, as this was already reported for fatigue in one of the included studies (Carlsen et al. 2013). More knowledge is needed to be able to know what subgroups are at risk and aim rehabilitation interventions at the right objectives. Furthermore, it is important to realize that the prevalence of late effects might also differ due to different types of treatment (Stein et al. 2008), while these differences are not always taken into account.

Fourth, the work status, the type of employment and the personal work histories of the study participants were not clear in a vast majority of the studies. Study samples did not in all instances include participants who had fully recovered 100% of their previous working hours currently or were not always entirely actively at work during the study’s data selection for unknown reasons. Only some studies mentioned type of work, like blue or white collar. Also, information on previous work adjustments, previous changes of job or of employer, was mostly not presented. So, results might be biased by those not actually active in work, by differences in type of work or already made adjustments in job demands made in an earlier stage. Furthermore, the setting of 75% of the studies was a European country, preventing global generalizability.

Fifth, only 13 (36%) of the 36 studies mentioned the inclusion of self-employed workers; freelancers, or entrepreneurs (Taskila and Lindbohm 2007; Gudbergsson et al. 2008a; Lee et al. 2008; De Boer et al. 2011; Torp et al. 2017, 2012; Moskowitz et al. 2014; Von Ah et al. 2017; Cheung et al. 2017; Hartung et al. 2018; Ortega et al. 2018; Wolvers et al. 2019; Tamminga et al. 2019). However, the self-employed might have different characteristics in regard to age, educational level, and gender and decision latitude, as was reported in one of the studies (Torp et al. 2017). Also, a recent European multi-country study (Torp et al. 2018), reported that differences in work ability could be observed between salaried and self-employed but that the direction and magnitude of these differences differed across countries. The variation between different kinds of self-employment should probably be considered too, as self-employment occurs in very different professional areas, and among the healthy population agricultural entrepreneurs, for instance, have a lower work ability than other occupational groups (Gould et al. 2000). The conclusion from this review is that the non-salaried workers among cancer survivors are reported to have a lower work ability than salaried workers. However, differentiation in occupational groups within the self-employed is not clear, stressing the need to take this into account as self-employment shows varying profiles. This review does not clarify whether predictors of lower work ability in this type of employment differ from the predictors of lower work ability in the salaried work situation. Nevertheless, the role of reduced working hours and a negative cancer-related financial change underlines that targets for occupational rehabilitation in this group of workers could also be interventions directed at business support, as some rehabilitation providers focusing on the self-employed are already offering. Future studies should focus on the needs of this specific group of the non-salaried workers with a past cancer diagnosis.

Finally, this review was limited to five well-known job-resources for the general working population. Other job resources, such as growth opportunities, performance feedback or organizational prestige, might also be relevant for the salaried, and also or even exclusively for the non-salaried. Furthermore, also personal resources are important (McGonagle et al. 2015), however these were not the focus of this review.

Strengths

This is the first review to focus on late effects of cancer treatment, work ability and job resources. This review combines findings on the effects of cancer treatment with work ability (Ilmarinen et al. 2005), and with the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al. 2001), which is unique to our knowledge. The goal of sustainable work participation of cancer survivors needs tailored interventions (De Boer et al. 2020b) and the outcome measure of work ability is an important factor in this research area. This review integrates concepts originated in different research disciplines with the intention to be able to focus on targets in the workplace to preserve and enhance work ability among workers experiencing late effects of cancer treatment beyond the first two years after cancer diagnosis.

Conclusion

To conclude, this systematic literature review confirms that a lowered work ability after the start of cancer treatment, might recover during the first two years after diagnosis. However, at two or more years beyond cancer diagnosis work ability might still be lower than before the cancer diagnosis. The course of work ability among workers beyond the first two years after diagnoses is unknown as no longitudinal data are available. Longitudinal research in salaried and non-salaried populations is needed to study in more detail what factors are important for sustainable occupational rehabilitation after cancer treatment. Besides this, an interesting methodological finding is that although the majority of the studies uses one of more items of the Work Ability Index (WAI) to assess work ability, also a substantive part of the included studies makes use of a variety of validated and non-validated measurement tools. The method to measure work ability did not seem to lead to different conclusions.

Physical complaints, fatigue and cognitive complaints may be present as late effects of cancer treatment beyond two years after diagnosis and can be associated with a lower level of work ability. However, data on the association between late effects and work ability is scarce. Furthermore, it is unknown if late effects of cancer treatment diminish work ability beyond two years after being diagnosed with cancer because longitudinal studies are lacking.

Furthermore, this review also makes clear that the job resources leadership style, coaching and organizational culture were not taken into account in studies on late effects of cancer treatment and work ability, and that for the job resources that were included (autonomy and social support in the workplace) no possible buffering effect was analyzed. However, autonomy and social support were associated with higher work ability and therefore are important for work functioning among workers past cancer diagnosis and it is recommended to enhance these job resources as much as possible.

This review indicates that there is an urgent need to close this gap in our knowledge. It is important to study late effects of cancer treatment, work ability and job resources in combination within studies among various samples of workers with a past cancer diagnosis, as well in large international cohorts. These studies need to be carried out beyond the first two years of cancer diagnosis. A focus on a broad range of job resources is essential, both for salaried and self-employed workers. It should be clear what range of job resources might accelerate a recovery of work ability, creating an important step towards clarifying the issue of the rehabilitation of work ability beyond return to work among workers with a history of cancer.

References

Ahlstrom L, Grimby-Ekman A, Hagberg M, Dellve L (2010) The work ability index and single-item question: associations with sick leave, symptoms, and health—a prospective study of women on long-term sick leave. Scand J Work Environ Heal 36:404–412. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.2917

Alavinia SM, de Boer AGEM, van Duivenbooden JC et al (2009) Determinants of work ability and its predictive value for disability. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 59:32–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqn148

Bains M, Munir F, Yarker J et al (2012) The impact of colorectal cancer and self-efficacy beliefs on work ability and employment status: a longitudinal study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 21:634–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2012.01335.x

Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Euwema MC (2005) Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. J Occup Health Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.170

Bender CM, Merriman JD, Gentry AL et al (2015) Patterns of change in cognitive function with anastrozole therapy. Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29393

Berg Gudbergsson S, Fosså SD, Dahl AA (2008) Is cancer survivorship associated with reduced work engagement? A NOCWO study. J Cancer Surviv 2:159–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-008-0059-9

Bielik J, Bystricky B, Hoffmannova K et al (2020) Quality of life and ability to work in ovarian cancer patients in Slovakia. Neoplasma 67:389–393. https://doi.org/10.4149/neo_2020_190401n285

Brady GM, Truxillo DM, Cadiz DM et al (2019) Opening the black box: examining the nomological network of work ability and its role in organizational research. J Appl Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000454

Cadiz DM, Brady G, Rineer JR, Truxillo DM (2019) A review and synthesis of the work ability literature. Work Aging Retire 5:114–138

Carlsen K, Jensen AJ, Rugulies R, et al (2013) Self-reported work ability in long-term breast cancer survivors. A population-based questionnaire study in Denmark. In: Acta Oncologica. pp 423–429

CBS (2019) Self-employment - The Netherlands on the European scale ( 2019 ) CBS. https://longreads.cbs.nl/european-scale-2019/self-employment/. Accessed 8 Jul 2019

Cheung K, Ching SYS, Chan A et al (2017) The impact of personal-, disease- and work-related factors on work ability of women with breast cancer living in the community:a cross-sectional survey study. Support Care Cancer 25:3495–3504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3773-x

Cormier JN, Askew RL, Mungovan KS et al (2010) Lymphedema beyond breast cancer. Cancer 116:5138–5149

Couwenberg AM, Intven MPW, Gregorowitsch ML et al (2020) Patient-reported work ability during the first two years after rectal cancer diagnosis. Dis Colon Rectum 63:1. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000001601

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018a) CASP Case Control Study Checklist

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018b) CASP Cohort Study Checklist

Dahl AA, Brennhovd B, Fosså SD, Axcrona K (2020) A cross-sectional study of current work ability after radical prostatectomy. BMC Urol 20:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-020-0579-9

Dahl AA, Fosså SD, Lie HC et al (2019) Employment status and work ability in long-term young adult cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 8:304–311. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2018.0109

Dahl S, Cvancarova M, Dahl AA, Fosså SD (2016) Work ability in prostate cancer survivors after radical prostatectomy. Scand J Urol 50:116–122. https://doi.org/10.3109/21681805.2015.1100674

De Boer AG, Torp S, Popa A et al (2020) Long-term work retention after treatment for cancer:a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00862-2

De Boer AGEM, Bruinvels DJ, Tytgat KMAJ et al (2011) Employment status and work-related problems of gastrointestinal cancer patients at diagnosis:a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 1:e000190. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000190

De Boer AGEM, Greidanus MA, Dewa CS et al (2020) Introduction to special section on: current topics in cancer survivorship and work. J Cancer Surviv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00868-w

De Boer AGEM, Taskila T, Ojajärvi A et al (2009) Cancer survivors and unemployment: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA 301:753–762. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.187

AGEM Boer De TK Taskila SJ Tamminga et al (2015) Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017

De Boer AGEM, Verbeek JHAM, Spelten ER et al (2008) Work ability and return-to-work in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 98:1342–1347. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604302

Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB (2001) The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol 86:499–512

Doll KM, Barber EL, Bensen JT et al (2016) The impact of surgical complications on health-related quality of life in women undergoing gynecologic and gynecologic oncology procedures: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 215:457

Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016

Drafts BC, Twomley KM, D’Agostino R et al (2013) Low to moderate dose anthracycline-based chemotherapy is associated with early noninvasive imaging evidence of subclinical cardiovascular disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 6:877–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.11.017

Duijts SFA, Kieffer JM, van Muijen P, van der Beek AJ (2017) Sustained employability and health-related quality of life in cancer survivors up to four years after diagnosis. Acta Oncol (Madr) 56:174–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2016.1266083

Dutch Federation of Cancer Patient Organizations NFK (2017) Late effects of cancer: what are your experiences? https://nfk.nl/resultaten/welke-ervaringen-zijn-er-met-de-late-gevolgen-van-kanker. Accessed 1 May 2020

Ehrhart MG, Schneider B (2016) Organizational Climate and Culture Organizational Climate. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. Oxford University Press, pp 1–26

El Fassi M, Bocquet V, Majery N et al (2013) Work ability assessment in a worker population: comparison and determinants of work ability index and work ability score. BMC Public Health 13:305. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-305

Fosså SD, Dahl AA (2015) Global quality of life after curative treatment for prostate cancer:what matters? a study among members of the norwegian prostate cancer patient association. Clin Genitourin Cancer 13:518–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clgc.2015.07.004

Ganz PA (2001) Late effects of cancer and its treatment. Semin Oncol Nurs 17:241–248. https://doi.org/10.1053/sonu.2001.27914

Gould R, Ilmarinen J, Järvisalo J, Koskinen S (2000) Dimensions of Work Ability. Results of the Health 2000 Survey

Gregorowitsch ML, van den Bongard HJGD, Couwenberg AM et al (2019) Self-reported work ability in breast cancer survivors:a prospective cohort study in the Netherlands. Breast 48:45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2019.08.004

Gudbergsson SB, Fosså SD, Dahl AA (2008a) Is cancer survivorship associated with reduced work engagement? a NOCWO Study. J Cancer Surviv 2:159–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-008-0059-9

Gudbergsson SB, Fosså SD, Dahl AA (2011) Are there sex differences in the work ability of cancer survivors? Norwegian experiences from the NOCWO study. Support Care Cancer 19:323–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0820-2

Gudbergsson SB, Fosså SD, Dahl AA (2008b) A study of work changes due to cancer in tumor-free primary-treated cancer patients. A NOCWO Study Support Care Cancer 16:1163–1171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0407-3

Hartung TJ, Sautier LP, Scherwath A et al (2018) Return to work in patients with hematological cancers 1 year after treatment:a prospective longitudinal study. Oncol Res Treat 41:697–701. https://doi.org/10.1159/000491589

Ho PJ, Hartman M, Gernaat SAM et al (2018) Associations between workability and patient-reported physical, psychological and social outcomes in breast cancer survivors:a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer 26:2815–2824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4132-2

Ilmarinen J, Tuomi K (2004) Past, present and future of work ability. 1st Int Symp Work Abil Helsinki

Ilmarinen J, Tuomi K, Seitsamo J (2005) New dimensions of work ability. Int Congr Ser 1280:3–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ics.2005.02.060

Keating NL, O’Malley AJ, Smith MR (2006) Diabetes and cardiovascular disease during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:4448–4456. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2497

Kiasuwa Mbengi R, Tiraboschi M, de Brouwer C, Bouland C (2018) How do social security schemes and labor market policies support the return-to-work of cancer survivors? A Rev Article J Cancer Policy 15:128–133

Kiserud CE, Fagerli U-M, Smeland KB et al (2016) Pattern of employment and associated factors in long-term lymphoma survivors 10 years after high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation. Acta Oncol (Madr) 55:547–553. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2015.1125015

Koolhaas W, Van der Klink JJL, de Boer MR et al (2013) Chronic health conditions and work ability in the ageing workforce: the impact of work conditions, psychosocial factors and perceived health. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 87:433–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-013-0882-9

Koppelmans V, Breteler MMB, Boogerd W et al (2012) Neuropsychological performance in survivors of breast cancer more than 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 30:1080–1086. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.37.0189

Lebel S, Ozakinci G, Humphris G et al (2016) From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer 24:3265–3268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3272-5

Lederer V, Loisel P, Rivard M, Champagne F (2014) Exploring the diversity of conceptualizations of work (dis)ability:a scoping review of published definitions. J Occup Rehabil 24:242–267

Lee MK, Lee KM, Bae JM et al (2008) Employment status and work-related difficulties in stomach cancer survivors compared with the general population. Br J Cancer 98:708–715. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604236

Leijten FRM, van den Heuvel SG, Ybema JF et al (2014) The influence of chronic health problems on work ability and productivity at work:a longitudinal study among older employees. Scand J Work Environ Health 40:473–482. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3444

Lindbohm ML, Taskila T, Kuosma E et al (2012) Work ability of survivors of breast, prostate, and testicular cancer in Nordic countries:a NOCWO study. J Cancer Surviv 6:72–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-011-0200-z

McGonagle AK, Fisher GG, Barnes-Farrell JL, Grosch JW (2015) Individual and work factors related to perceived work ability and labor force outcomes. J Appl Psychol 100:376–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037974

Mehnert A (2011) Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 77:109–130

Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC et al (2016) Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 66:271–289. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21349

Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J et al (2013) Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 14:721–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70244-4

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses:the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Moskowitz MC, Todd BL, Chen R, Feuerstein M (2014) Function and friction at work:a multidimensional analysis of work outcomes in cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 8:173–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0340-4

Munir F, Yarker J, McDermott H (2009) Employment and the common cancers: correlates of work ability during or following cancer treatment. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 59:381–389. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqp088

Musti MA, Collina N, Stivanello E et al (2018) Perceived work ability at return to work in women treated for breast cancer:a questionnaire-based study. Med del Lav 109:407–419. https://doi.org/10.23749/mdl.v110i6.7241

Neudeck MR, Steinert H, Moergeli H et al (2017) Work ability and return to work in thyroid cancer patients and their partners:a pilot study. Psychooncology 26:556–559. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4154

Nieuwenhuijsen K, de Boer A, Spelten E et al (2009) The role of neuropsychological functioning in cancer survivors’ return to work one year after diagnosis. Psychooncology 18:589–597. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1439

Nilsson MI, Saboonchi F, Alexanderson K et al (2016) Changes in importance of work and vocational satisfaction during the 2 years after breast cancer surgery and factors associated with this. J Cancer Surviv 10:564–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0502-7

Ortega CCF, Veiga DF, Camargo K et al (2018) Breast reconstruction may improve work ability and productivity after breast cancer surgery. Ann Plast Surg 81:402–406. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000001562

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 5:210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Prue G, Rankin J, Allen J et al (2006) Cancer-related fatigue:a critical appraisal. Eur J Cancer 42:846–863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.026

Radkiewicz P, Widerszal-Bazyl M (2005) Psychometric properties of work ability index in the light of comparative survey study. Int Congr Ser 1280:304–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ics.2005.02.089

Reinertsen KV, Cvancarova M, Loge JH et al (2010) Predictors and course of chronic fatigue in long-term breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 4:405–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-010-0145-7

Servaes P, Gielissen MFM, Verhagen S, Bleijenberg G (2007) The course of severe fatige in disease-free breast cancer patients:a longitudinal study. Psychooncology 16:787–795. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon

Silver JK, Baima J, Newman R et al (2013) Cancer rehabilitation may improve function in survivors and decrease the economic burden of cancer to individuals and society. Work 46:455–472. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-131755

Spelten E, Sprangers MAG, Verbeek JHAM (2002) Factors reported to influence the return to work of cancer survivors:a literature review. Psychooncology 11:124–131. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.585

Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA (2008) Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer 112:2577–2592. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23448

Stewart B, Wild C (2014) World Cancer Report 2014. WHO Press

Tamminga SJ, Verbeek JHAM, Bos MMEM et al (2019) Two-year follow-up of a multi-centre randomized controlled trial to study effectiveness of a hospital-based work support intervention for cancer patients. J Occup Rehabil 29:701–710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-019-09831-8

Taskila T, Lindbohm ML (2007) Factors affecting cancer survivors’ employment and work ability. Acta Oncol (Madr) 46:446–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860701355048

Taskila T, Martikainen R, Hietanen P, Lindbohm M-L (2007) Comparative study of work ability between cancer survivors and their referents. Eur J Cancer 43:914–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.012

Tikka C, Verbeek J, Tamminga S, et al (2017) Rehabilitation and return to work after cancer: literature review. Luxembourg: EU-OSHA. 44. 10.2802/712

Torp S, Nielsen RA, Gudbergsson SB, Dahl AA (2012) Worksite adjustments and work ability among employed cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 20:2149–2156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1325-3

Torp S, Paraponaris A, Van Hoof E et al (2018) Work-related outcomes in self-employed cancer survivors:a European multi-country study. J Occup Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9792-8

Torp S, Syse J, Paraponaris A, Gudbergsson S (2017) Return to work among self-employed cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 11:189–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0578-8

van de Berg TIJ, Elders LAM, Burdorf A (2010) Influence of health and work on early retirement. J Occup Environ Med 52:576–583. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181de8133

Von Ah D, Storey S, Crouch A (2018) Relationship between self-reported cognitive function and work-related outcomes in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 12:246–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0664-6

Von Ah D, Storey S, Crouch A et al (2017) Relationship of self-reported attentional fatigue to perceived work ability in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 40:464–470. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000444

Wefel JS, Kesler SR, Noll KR, Schagen SB (2015) Clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management of noncentral nervous system cancer-related cognitive impairment in adults. CA Cancer J Clin 65:123–138. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21258

Wolvers MDJ, Leensen MCJ, Groeneveld IF et al (2019) Longitudinal associations between fatigue and perceived work ability in cancer survivors. J Occup Rehabil 29:540–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9814-6

World Health Organization (2012) GLOBOCAN Fact Sheets by. Cancer 2012:4

Xanthopoulou D, Bakker AB, Dollard MF et al (2007) When do job demands particularly predict burnout? the moderating role of job resources. J Manag Psychol 22:766–786. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710837714

Zanville NR, Nudelman KNH, Smith DJ et al (2016) Evaluating the impact of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy symptoms (CIPN-sx) on perceived ability to work in breast cancer survivors during the first year post-treatment. Support Care Cancer 24:4779–4789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3329-5

Acknowledgements

We thank Janneke Staaks and Jolanda Kleen, information specialists, for providing the needed selection parameters for the various databases and performing the searches. Furthermore, we thank our two research trainees, Dana Landman and Sterre Albrecht, for their individual effort to screen the search results by title and abstract.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

First author IGB: defined search terms in collaboration with an information specialist in mutual agreement with the other authors, screened by title and abstract in collaboration with the second author and two research trainees, performed citation tracking and the data extraction, discussed the eligibility of the papers after the screening, the quality assessment, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and performed the drafting and the critical revision of the manuscript. Second author WV: screened by title and abstract in collaboration with the first author, discussed the eligibility of the papers after the screening, the quality assessment, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and contributed to the drafting and the critical revision of the manuscript. Third author TvV: discussed the eligibility of the papers after the screening, the quality assessment, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and contributed to the drafting and the critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boelhouwer, I.G., Vermeer, W. & van Vuuren, T. The associations between late effects of cancer treatment, work ability and job resources: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 94, 147–189 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-020-01567-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-020-01567-w