Abstract

Purpose

Visual acuity (VA) is an important determinant of visual function. Here we establish procedures and recommendations for VA testing extending beyond the classical VA and thus make them available for future studies of visual function in health and disease. Specifically, we provide reference values for photopic and scotopic conventional uncrowded visual acuity (cVA) and Vernier-hyperacuity (hVA) and assess their reproducibility and dependence on contrast polarity.

Methods

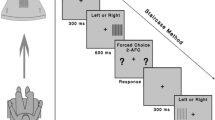

For ten observers with normal vision, we determined photopic (“p”; maximal luminance 220 cd/m2) and scotopic (“s”; maximal luminance 0.004 cd/m2; 40 min of dark adaptation) cVA and hVA, for two contrast polarities i.e. black optotypes on white background and vice versa. To assess intersession effects, two sets of measurements were obtained on different days.

Results

Compared to pcVA (1.32 decimal VA; − 0.12 ± 0.02 LogMAR), the phVA (14.45 decimal VA; − 1.16 ± 0.04 LogMAR) scaled (in terms of decimal visual acuity) on average with a factor 11.0, the scVA (0.12 decimal VA; 0.91 ± 0.03 LogMAR) with a factor of 0.1, and the shVA (1.47 decimal VA; − 0.17 ± 0.02 LogMAR) with a factor of 1.1. There were neither significant effects of contrast polarity (p > 0.12), nor of session (p > 0.28).

Conclusions

Our approach optimises integrated photopic and scotopic cVA and hVA measurements for general use and thus encourages the integration of these important measures of scotopic visual function in future studies. The absence of strong intersession effects demonstrates that no dedicated training session is needed to obtain scotopic and hVA measurements. The combined measures of scotopic and photopic VAs open a field of applications to study interplay and plasticity of the retinal photoreceptor systems and cortical processing in health and visual disease. As a rule of thumb, hyperacuity is 10× higher both in the photopic and scotopic range than conventional acuity. Thus, scotopic hyperacuity is close to photopic conventional acuity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In order to avoid confusion, in terms of visual acuities, we refer to ‘better’ and ‘worse’ instead of ‘higher’ and ‘lower’, as the latter terms have opposite meanings for LogMAR and decimal visual acuity.

References

Levenson JH, Kozarsky A (1990) Visual acuity. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW (eds) Clinical methods: the history, physical, and laboratory examinations, 3rd edn. Butterworths, Boston

Westheimer G, Bass M (2010) Visual acuity and hyperacuity//vision and vision optics, 3. ed./sponsored by the Optical Society of America. In: Bass M (ed) Handbook of optics, vol 3. McGraw-Hill, New York

Bondarko VM, Danilova MV (1997) What spatial frequency do we use to detect the orientation of a Landolt C? Vis Res 37:2153–2156. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0042-6989(97)00024-2

Livingstone MS, Hubel DH (1994) Stereopsis and positional acuity under dark adaptation. Vis Res 34:799–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/0042-6989(94)90217-8

Poggio T, Fahle M, Edelman S (1992) Fast perceptual learning in visual hyperacuity. Science 256:1018–1021

Westheimer G (1987) Visual acuity and hyperacuity: resolution, localization, form. Am J Optom Physiol Optic 64:567–574

Westheimer G, McKee PS (1977) Integration regions for visual hyperacuity. Vis Res:89–93

Duncan RO, Boynton GM (2003) Cortical magnification within human primary visual cortex correlates with acuity thresholds. Neuron 38:659–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00265-4

Poggio T, Edelman S, Fahle M (1992) Learning of visual modules from examples. CVGIP Image Underst 56:22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/1049-9660(92)90082-E

Levi DM, Klein SA, Aitsebaomo AP (1985) Vernier acuity, crowding and cortical magnification. Vis Res 25:963–977. https://doi.org/10.1016/0042-6989(85)90207-X

Hecht S (1928) The relation between visual acuity and illumination. J Gen Physiol 11:255–281

König A (1897) Die Abhängigkeit der Sehschärfe von der Beleuchtungsintensität. Akad Wiss Phys-Math Kl

Roelofs CO, Zeeman WPC (1919) Die Sehschärfe im Halbdunkel, zugleich ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Nachtblindheit. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Für Ophthalmol 99:174–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02175135

Curcio CA, Sloan KR, Kalina RE, Hendrickson AE (1990) Human photoreceptor topography. J Comp Neurol 292:497–523. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.902920402

Osterberg G (1935) Topography of the layer of rods and cones in the human retina. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl 6:1–103

Baseler HA, Brewer AA, Sharpe LT et al (2002) Reorganization of human cortical maps caused by inherited photoreceptor abnormalities. Nat Neurosci 5:364–370. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn817

Zobor D, Werner A, Stanzial F et al (2017) The clinical phenotype of cnga3-related achromatopsia: pretreatment characterization in preparation of a gene replacement therapy trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 58:821–832. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.16-20427

Kampmeier J, Zorn MMC, Lang GK et al (2006) Vergleich des preferential-hyperacuity-perimeter (PHP)-tests mit dem Amsler-Netz-test bei der diagnose verschiedener Stadien der altersbezogenen Makuladegeneration. Klin Monatsblätter Für Augenheilkd 223:752–756. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-926880

Loewenstein A, Malach R, Goldstein M et al (2003) Replacing the Amsler grid: a new method for monitoring patients with age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 110:966–970. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00074-5

Querques G, Berboucha E, Leveziel N et al (2011) Preferential hyperacuity perimeter in assessing responsiveness to ranibizumab therapy for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol 95:986–991. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2010.190942

Yu S-Y, Kwak H-W, Kim M (2014) Association between hyperacuity defects and retinal microstructure in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol 62:702. https://doi.org/10.4103/0301-4738.121132

Simunovic MP (2015) metamorphopsia and its quantification. Retina 35:1285. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000000581

Faes L, Bodmer NS, Bachmann LM et al (2014) Diagnostic accuracy of the Amsler grid and the preferential hyperacuity perimetry in the screening of patients with age-related macular degeneration: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eye 28:788–796. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2014.104

Group PHP (php) R (2005) Results of a multicenter clinical trial to evaluate the preferential hyperacuity perimeter for detection of age-related macular degeneration. Retina 25:296

Meier K, Giaschi D (2017) Unilateral amblyopia affects two eyes: fellow eye deficits in amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 58:1779–1800. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.16-20964

Dallala R, Wang Y-Z, Hess RF (2010) The global shape detection deficit in strabismic amblyopia: contribution of local orientation and position. Vis Res 50:1612–1617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2010.05.023

Subramanian V, Morale SE, Wang Y-Z, Birch EE (2012) Abnormal radial deformation hyperacuity in children with strabismic amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53:3303. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.11-8774

Watt RJ, Hess RF (1987) Spatial information and uncertainty in anisometropic amblyopia. Vis Res 27:661–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/0042-6989(87)90050-2

Bach M (2016) Manual of the Freiburg Vision Test “FrACT”, Version 3.9.8. http://docplayer.net/37653824-Manual-of-the-freiburg-vision-test-fract-version-3-9-8.html. Accessed 5 Jun 2019

Bach M, Schäfer K (2016) Visual acuity testing: feedback affects neither outcome nor reproducibility, but leaves participants happier. PLoS One 11:e0147803 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147803

Holm S (1979) A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 6:65–70

Martin Bland J, Altman Douglas G (1986) Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical. Lancet 327:307–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8

Wilson HR (1986) Responses of spatial mechanisms can explain hyperacuity. Vis Res 26:453–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/0042-6989(86)90188-4

Crist RE, Kapadia MK, Westheimer G, Gilbert CD (1997) Perceptual learning of spatial localization: specificity for orientation, position, and context. J Neurophysiol 78:2889–2894. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.2889

Fahle M, Edelman S (1993) Long-term learning in vernier acuity: effects of stimulus orientation, range and of feedback. Vis Res 33

Shlaer S (1937) The relation between visual acuity and illumination. J Gen Physiol 21:165–188

Fahle M, Edelman S, Poggio T (1995) Fast perceptual learning in hyperacuity. Vis Res 35:3003–3013. https://doi.org/10.1016/0042-6989(95)00044-Z

Fendick M, Westheimer G (1983) Effects of practice and the separation of test targets on foveal and peripheral stereoacuity. Vis Res 23:145–1540

Mckee SP, Westheimer G (1978) Improvement in Vernier acuity with practice. Percept Psychophys 24:258–262. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206097

Heinrich SP, Krüger K, Bach M (2011) The dynamics of practice effects in an optotype acuity task. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 249:1319–1326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-011-1675-z

Petersen J (1993) Fehlerhafte Visusbestimmung und ihre quantitativen Auswirkungen. Ophthalmologe:533–538

Petersen J (1990) Zur Fehlerbreite der subjektiven Visusmessung. Ophthalmologe:604–608

Meyer CH, Lapolice DJ, Fekrat S (2005) Functional changes after photodynamic therapy with verteporfin. Am J Ophthalmol 139:214–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2004.07.034

Westheimer G (2003) Visual acuity with reversed-contrast charts: I. Theoretical and psychophysical investigations. Optom Vis Sci Off Publ Am Acad Optom 80:745–748

Westheimer G, Chu P, Huang W et al (2003) Visual acuity with reversed-contrast charts: II. Clinical investigation. Optom Vis Sci Off Publ Am Acad Optom 80:749–752

Beck J, Schwartz T (1979) Venier acuity with dot test objects. Vis Res 19:313–319

Poggio T (1990) A theory of how the brain might work. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 55:899–910. https://doi.org/10.1101/SQB.1990.055.01.084

Bach M (1996) The Freiburg visual acuity test- automatic measurement of visual acuity. Optom Vis Sci:49–53

McCulloch DL, Marmor MF, Brigell MG et al (2015) ISCEV standard for full-field clinical electroretinography (2015 update). Doc Ophthalmol 130:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-014-9473-7

Funding

This study was funded by the DFG (HO2002/12-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethical Committee of the University of Magdeburg, Germany, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

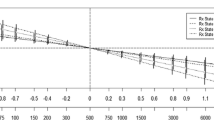

Suppl. Fig. 1

Relation of individual acuities (photopic and scotopic hVA, and scotopic cVA) with photopic cVA. No significant correlations between the acuities were evident. The coefficients of determination (r2) are given. Shading indicates SEMs. Note the inverted axes for the LogMAR values. (PNG 276 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Freundlieb, P.H., Herbik, A., Kramer, F.H. et al. Determination of scotopic and photopic conventional visual acuity and hyperacuity. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 258, 129–135 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-019-04505-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-019-04505-w