Abstract

Background

Tay–Sachs disease (TSD) is an inherited neurodegenerative disorder caused by a lysosomal β-hexosaminidase A deficiency due to mutations in the HEXA gene. The late-onset form of disease (LOTS) is considered rare, and only a limited number of cases have been reported. The clinical course of LOTS differs substantially from classic infantile TSD.

Methods

Comprehensive data from 14 Czech patients with LOTS were collated, including results of enzyme assays and genetic analyses.

Results

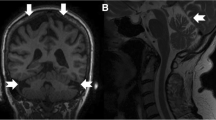

14 patients (9 females, 5 males) with LOTS were diagnosed between 2002 and 2018 in the Czech Republic (a calculated birth prevalence of 1 per 325,175 live births). The median age of first symptoms was 21 years (range 10–33 years), and the median diagnostic delay was 10.5 years (range 0–29 years). The main clinical symptoms at the time of manifestation were stammering or slurred speech, proximal weakness of the lower extremities due to anterior horn cell neuronopathy, signs of neo- and paleocerebellar dysfunction and/or psychiatric disorders. Cerebellar atrophy detected through brain MRI was a common finding. Residual enzyme activity was 1.8–4.1% of controls. All patients carried the typical LOTS-associated c.805G>A (p.Gly269Ser) mutation on at least one allele, while a novel point mutation, c.754C>T (p.Arg252Cys) was found in two siblings.

Conclusion

LOTS seems to be an underdiagnosed cause of progressive distal motor neuron disease, with variably expressed cerebellar impairment and psychiatric symptomatology in our group of adolescent and adult patients. The enzyme assay of β-hexosaminidase A in serum/plasma is a rapid and reliable tool to verify clinical suspicions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gravel RA, Kaback MM, Proia RL, et al (2014) The GM2 Gangliosidoses. In: The online metabolic and molecular bases of inherited diseases

Kaback MM, Desnick RJ (2011) Hexosaminidase A deficiency. In: Pagon R, Adam M (eds) GenReviews, pp 1993–2018

Chen H, Chan AY, Stone DU, Mandal NA (2014) Beyond the cherry-red spot: Ocular manifestations of sphingolipid-mediated neurodegenerative and inflammatory disorders. Surv. Ophthalmol. 59:64–76

Kaback M, Lim-Steele J, Dabholkar D et al (1994) Tay–Sachs disease—carrier screening, prenatal diagnosis and the molecular era: an international perspective, 1970 to 1993. Obstet Gynecol Surv 270:2307–2315. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006254-199405000-00013

Kaback MM (2000) Population-based genetic screening for reproductive counseling: the Tay–Sachs disease model. Eur J Pediatr 159:192–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00014401

Scott SA, Edelmann L, Liu L et al (2010) Experience with carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for 16 Ashkenazi Jewish genetic diseases. Hum Mutat 31:1240–1250. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.21327

Neudorfer O, Pastores GM, Zeng BJ et al (2005) Late-onset Tay–Sachs disease: phenotypic characterization and genotypic correlation in 21 affected patients. Genet Med 7:119–123

Steiner KM, Brenck J, Goericke S, Timmann D (2016) Cerebellar atrophy and muscle weakness: late-onset Tay–Sachs disease outside Jewish populations. BMJ Case Rep 31:5

Barritt AW, Anderson SJ, Leigh PN, Ridha BH (2017) Late-onset Tay–Sachs disease. Pract Neurol 17:396–399. https://doi.org/10.1136/practneurol-2017-001665

Prihodova I, Kalincik T, Poupetova H et al (2013) Late-onset Tay–Sachs disease can mimic spinal muscular atrophy type III—two case reports. Ces a Slov Neurol a Neurochir 76:221–224

Navon R, Argov Z, Frisch A (1986) Hexosaminidase A deficiency in adults. Am J Med Genet 24:179–196. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.1320240123

Wenger D, Williams C (1991) Screening for lysosomal disorders. In: Hommes FA (ed) Techniques in diagnostic human biochemical genetics. Willey-Liss, New York, pp 587–617

HEXA hexosaminidase subunit alpha [Homo sapiens (human)]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/3073. Accessed 30 Sep 2018

Human genom variation society. https://www.hgvs.org/. Accessed 17 Sep 2018

Streifler J, Golomb M, Gadoth N (1989) Psychiatric features of adult GM2gangliosidosis. Br J Psychiatry 155:410–413. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.155.3.410

MacQueen GM, Rosebush PI, Mazurek MF (1998) Neuropsychiatric aspects of the adult variant of Tay–Sachs disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 10:10–19. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.10.1.10

Navon R, Proia RL (1989) The mutations in Ashkenazi Jews with adult GM2gangliosidosis, the adult form of Tay–Sachs disease. Science 243:1471–1474. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2522679

Stepien KM, Lum SH, Wraith JE et al (2017) Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation arrests the progression of neurodegenerative disease in late-onset Tay–Sachs disease. JIMD Rep 41:17–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/8904_2017_76

Neudorfer O, Kolodny EH (2004) Late-onset Tay–Sachs disease. Isr Med Assoc J 6:107–111

von Specht BU, Geiger B, Arnon R et al (1979) Enzyme replacement in Tay–Sachs disease. Neurology 29:848–854. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.29.6.848

Shapiro BE, Pastores GM, Gianutsos J et al (2009) Miglustat in late-onset Tay–Sachs disease: a 12-month, randomized, controlled clinical study with 24 months of extended treatment. Genet Med 11:425–433. https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181a1b5c5

Osher E, Fattal-Valevski A, Sagie L et al (2015) Effect of cyclic, low dose pyrimethamine treatment in patients with Late Onset Tay Sachs: an open label, extended pilot study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 17:10–45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-015-0260-7

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Grant UNCE 204064; PROGRES Q26/LF1 and RVO-VFN 64165/2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jahnová, H., Poupětová, H., Jirečková, J. et al. Amyotrophy, cerebellar impairment and psychiatric disease are the main symptoms in a cohort of 14 Czech patients with the late-onset form of Tay–Sachs disease. J Neurol 266, 1953–1959 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09364-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09364-3