Abstract

Rhyolite flows and tuffs from the Long Valley area of California, which were erupted over a two-million-year time period, exhibit systematic trends in Nd, Hf, and Pb isotopes, trace element composition, erupted volume, and inferred magma residence time that provide evidence for a new model for the production of large volumes of silica-rich magma. Key constraints come from geochronology of zircon crystal populations combined with a refined eruption chronology from Ar–Ar geochronology; together these data give better estimates of magma residence time that can be evaluated in the context of changing magma compositions. Here, we report Hf, Nd, and Sr isotopes, major and trace element compositions, 40Ar/39Ar ages, and U–Pb zircon ages that combined with existing data suggest that the chronology and geochemistry of Long Valley rhyolites can be explained by a dynamic interaction of crustal and mantle-derived magma. The large volume Bishop Tuff represents the culmination of a period of increased mantle-derived magma input to the Long Valley volcanic system; the effect of this input continued into earliest postcaldera time. As the postcaldera evolution of the system continued, new and less primitive crustal-derived magmas dominated the system. A mixture of varying amounts of more mafic mantle-derived and felsic crustal-derived magmas with recently crystallized granitic plutonic materials offers the best explanation for the observed chronology, secular shifts in Hf and Nd isotopes, and the apparently low zircon crystallization and saturation temperatures as compared to Fe–Ti oxide eruption temperatures. This scenario in which transient crustal magma bodies remained molten for varying time periods, fed eruptions before solidification, and were then remelted by fresh recharge provides a realistic conceptual framework that can explain the isotopic and geochemical evidence. General relationships between crustal residence times and magma sources are that: (1) precaldera rhyolites had long crustal magma residence times and high crustal affinity, (2) the caldera-related Bishop Tuff and early postcaldera rhyolites have lower crustal affinity and short magma residence times, and (3) later postcaldera rhyolites again have stronger crustal signatures and longer magma residence times.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The dynamics by which silicic magmas are generated in continental volcanic centers remain debated. This is due to their complex formation processes involving crust and mantle source components, lack of direct observations of the physical nature in which they reside in the crust, and ambiguities regarding their temporal evolution and extent to which they have a direct petrogenetic relationship with plutonic rocks. Canonical models propose efficient liquid separation from a crystal mush (e.g., Bachmann and Bergantz 2004; Hildreth and Wilson 2007) in which granitoids reflect crystal cumulates from which the silicic melts have been largely removed before or during eruption (Bacon and Lowenstern 2005; Johnson et al. 1989; Lipman 2007). Such models imply that associated with the generation of ignimbrite extrusions are significant volumes of subvolcanic magma that solidified as plutons that may be up to an order of magnitude larger than the erupted material (e.g., Bachmann et al. 2007; Halliday et al. 1989; Lipman 2007). The opposing views suggest that shallowly emplaced granitoids are often not the unerupted portion of volcanic rocks (Glazner et al. 2008), that plutons accumulate incrementally (Coleman et al. 2004; Davis et al. 2012), and that there are no long-lived magma chambers (e.g., Sparks et al. 1990). Inextricably linked to these models are issues related to the time interval over which such evolved magmas are stored and rejuvenated in the crust.

Coeval caldera collapse and ignimbrite eruption are conventionally thought to result from the partial evacuation of voluminous differentiated magma chambers in the shallow crust (Smith, 1979). Long-term eruption rates (Crisp 1984; Spera and Crisp 1981; White et al. 2006) and early compilation studies of crystal ages and crystal size distribution analysis (CSD) indicate that magma storage time tends to increase exponentially as SiO2 and stored magma volume increase (Hawkesworth et al. 2004; Reid 2003). These observations have been used to support the idea that longer magma storage times allow for evolved magmas to form and, in turn, result in longer repose periods associated with more felsic magmas—consistent with the long-lived mush magma chamber model. Yet, some recent investigations suggest that large volumes of silicic melts may be stored for intervals of time that are considerably shorter than the repose intervals typically seen between major silicic eruptions (Crowley et al. 2007; Druitt et al. 2012; Reid 2008; Reid and Coath 2000; Simon and Reid 2005; Simon et al. 2008a, b, 2009) or the rates of incremental emplacement of large plutonic suites (Coleman et al. 2004; Glazner et al. 2004; Matzel et al. 2006; Michel et al. 2008; Mills and Coleman 2013; Tappa et al. 2011).

Related to protracted magma residence time are the thermal requirements needed to maintain conditions where magma will remain at least partially molten in the crust (e.g., Annen 2009; Glazner et al. 2004). The primary parameters that dictate subvolcanic temperature conditions are the ambient crustal temperature (geothermal gradient) and the supply rate of basaltic magma to the volcanic system from the mantle. Because crustal and mantle reservoirs often have distinct isotopic compositions (e.g., Nd and Hf), these signatures can be used to track the source components of felsic magmas. High mafic magma influx into the crust and low crustal temperatures favors the formation of silicic magmas with mantle-like isotopic signatures, whereas low mafic input and high crustal temperatures favor the generation of melts that are relatively undiluted with mantle-derived magma and which therefore have more crustal isotopic signatures. Likewise, the rejuvenation rate of long-lived magmatic systems by more primitive magma(s) can be investigated by the rate at which the isotopic compositions of spatially related silicic extrusions change over time (DePaolo et al. 1992; Perry et al. 1993).

Here, we address the temporal evolution of silicic magmas at Long Valley caldera, California (Fig. 1), the “supervolcano” that produced the Bishop Tuff. Our goal is to understand how the caldera-forming Bishop Tuff magmas relate to those erupted as pre- and postcaldera rhyolites. This is accomplished primarily by integrating new Hf and Nd isotopic data and compositional data with literature Nd isotopic data (Davies and Halliday 1998; Davies et al. 1994; Heumann and Davies 1997) and new and published 40Ar/39Ar eruption ages and U–Pb zircon crystallization ages (Mankinen et al. 1986; Reid et al. 1997; Simon and Reid 2005; Simon et al. 2007, 2008b, 2009). New data are reported for precaldera rhyolite samples collected for previous investigations (Simon and Reid 2005; Simon et al. 2007) and from new samples collected from postcaldera rhyolites and the Bishop Tuff specifically for this study. Temporal variations of Hf and Nd isotope and trace element ratios (e.g., U/Th and La/Nd) of the rhyolites, and in some cases their zircon crystals, are used to probe the differentiation, physical nature, and ultimately the dynamics of the long-lived volcanic system. Given the relatively short time intervals measured between preeruption crystallization and eruption ages, we suggest that some rhyolite magmas at Long Valley were produced rapidly. Of importance is the fact that the age data provide little evidence for longer magma storage times for larger eruptions, in particular the Bishop Tuff (e.g., Crowley et al. 2007; Simon and Reid 2005; Simon et al. 2008a, b). Additionally, more primitive Hf and Nd isotopic and trace element signatures tend to be correlated with larger extruded magma volumes implying that mantle-derived influx expedites both the production of rhyolitic magma and its eruption at Long Valley. These results are difficult to reconcile with conventional ideas that large eruptions are derived from gradual buildup of large, long-lived, shallow magma bodies. Rather, they imply that the production of rhyolite magmas was accelerated by emplacement or underplating of more primitive magmas and that both types of magma were relatively transient features in the crust.

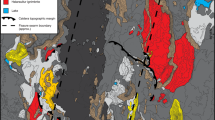

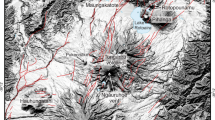

Simplified geologic maps of the Long Valley caldera (top) and surrounding area (bottom) showing the sample locations of the studied rhyolites, including the caldera-related Bishop Tuff, precaldera Glass Mountain domes and flows, and postcaldera rhyolites. Also shown are the locations of Deer Mountain and South Deadman Domes. The maps were derived by overlaying the map of Bailey (1989) on the digital topography provided by Google Earth®. Specific sample latitude and longitude provided in Tables 1 and 3

Samples and Analytical Techniques

Whole rock Hf and Nd isotopic compositions and zircon Hf isotopic compositions were measured for select postcaldera Long Valley rhyolites and Bishop Tuff pumice samples that were collected from localities of Christensen and DePaolo (1993) and following stratigraphy of Wilson and Hildreth (1997). Feldspar separates and/or host obsidian glasses were dated by 40Ar/39Ar methods for these rhyolites. New U–Pb zircon ages were determined for two postcaldera rhyolites. Hf, Nd, and Sr isotopic compositions were measured for a representative suite of Long Valley rhyolite samples previously studied by Christensen and DePaolo (1993), Reid and Coath (2000), Schmitt and Simon (2004), Simon and Reid (2005), and Simon et al. (2007). Zircon Hf isotopic compositions were also analyzed in several of these samples. Major and trace element abundances were measured in most of these. This study along with its predecessors (Schmitt and Simon 2004; Simon and Reid 2005; Simon et al. 2007) represents the most complete coordinated geochemical and geochronological sampling of the precaldera, Bishop Tuff, and postcaldera rhyolites from Long Valley, California (Fig. 1; Table 1). Whenever possible, we cite the 40Ar/39Ar ages measured by Simon et al. (2007), (2008b) and those reported herein, which provide the most accurate and internal consistent timeline for the volcanic history of rhyolites at Long Valley. Moreover, the U–Th–Pb zircon ages of Reid and Coath (2000), Reid et al. (1997), Simon and Reid (2005), and Simon et al. (2007) and those reported herein are used to address the ages that may pertain to preeruption “magma residence” timescales. The new 40Ar/39Ar ages help strengthen previously reported temporal geochemical trends (cf. Davies and Halliday 1998, reference therein, and this study) and a lower age limit with which to compare published U–Pb zircon ages (obtained by both high spatial resolution and bulk crystal techniques). Unless stated otherwise all reported uncertainties are 1σ.

Hf isotope methods for measurement of zircon and rhyolite host rocks

To further understand existing geochemical variations (e.g., trace elements and Sr, Nd, and Pb isotopes) and to evaluate evidence for open-system processes within Long Valley rhyolites, Hf isotopes were measured for individual large and groups of smaller zircon grains (Fig. 2) and associated whole rock materials (Tables 1, 2). For Hf analysis, zircons were dissolved intact, while pumice and glass chips were powdered prior to dissolution. Prior to dissolution of zircon, adhering host glass was removed by a short (~1 min), dilute hydrofluoric acid (~7 %), ultrasonic bath followed by an ultrasonic bath in distilled water. Occasionally, a second ultrasonic hydrofluoric acid bath was needed. Both zircon and whole rocks were dissolved by high pressure and high temperature in Teflon® vessels. The zircon grains were processed through the low blank U–Pb zircon dissolution procedures employed at the Berkeley Geochronology Center (Krogh 1973; Mundil et al. 2004) using sealed Krogh-style vessels. Acid digestion was carried out at 180 °C in a two-step process with both HF + HNO3 (respectively 15 and 5 μl) and 6 N HCl (25 μl). About 100 mg of selected rhyolite whole rock powders was dissolved in two steps at high pressure and high temperature (225 and then 120 °C) at the Center for Isotope Geochemistry (CIG) at the University of California Berkeley and at the Pacific Centre for Isotope and Geochemical Research (PCIGR) at the University of British Columbia. Acid digestion at CIG was carried out in a loosely caped vessel contained within a larger sealed vessel first with concentrated HF + 4 N HNO3 (respectively ~900 and 100 μl) and then 4 N HCl (~500 μl). Any fluorides formed upon drying were redissolved with a mixture of HClO4 (~150 μl) and 4 N HNO3 (~500 μl) at 120 °C on a hot plate over night. Whole rock dissolutions at the PCIGR were performed as in Pretorius et al. (2006). Chromatographic purification of Hf from zircon and whole rocks was performed using procedures employed at the PCIGR originally developed by Goolaerts et al. (2004). The well-characterized zircon standard 91500 and USGS granite rock standard G-2 were processed along with the zircon and rhyolite samples. Analyses were carried out on a Nu Plasma MC-ICPMS-MS at the PCIGR. Samples were run on four separate days. Internal normalization was made using the well-characterized ULB-JMC Hf isotope standard (JMC 475), assuming a 176Hf/177Hf value of 0.282160. Sample measurements were bracketed by analysis of JMC 475 to monitor and potentially correct for drift in instrument mass bias within and among individual sessions. Standard-sample-standard bracketing was applied if JMC 475 176Hf/177Hf values drifted more than 0.000014. In most sessions, there was minimal drift so just the daily average of JMC475 analyses was used for normalization. A 1σ precision of ±0.0000025 equating to a 2 σ uncertainty of ±0.2 epsilon (ε Hf) units was typical for individual sample analysis, where ε Hf = 104 × ((176Hf/177Hf − 176Hf/177HfCHUR)/176Hf/177HfCHUR). Hf purified from one of two separate fragments of zircon standard 91500 (Wiedenbeck et al. 1995) (n = 5) was analyzed in each session and yielded an average 176Hf/177Hf value of 0.282305 ± 7 (SD) that was indistinguishable from the accepted reference value of 0.282302 ± 8 (Goolaerts et al. 2004). The external reproducibility of 91500 was ±0.2 ε units. For all calculations, a 176Hf/177Hf CHUR value of 0.282772 was used. The 176Hf/177Hf value measured for the USGS granite standard G-2 of 0.282518 ± 2 compares favorably to the accepted reference value of 0.282523 ± 6 (Weis et al. 2007).

Hf isotope compositions of zircon in Hot Creek flow (JS06MLV27) and North Moat (JS06MLV25 and 26) postcaldera rhyolites (top), Bishop Tuff (JS09MLV32, MR99LV58, MR99LV51) pumice fragments (middle), and Glass Mountain dome OD (MR00LV63) precaldera rhyolite (bottom). Petrographic transmitted light images of representative zircon analyzed are shown. Most analyzed zircon crystals were euhedual to subhedual and equant; mineral and glass inclusions were common. A fraction of grains in JS06MLV27 that was euhedual and elongated (example shown) yielded a high ε Hf value of about +4. One anomalous analysis from the Bishop Tuff yielded a low ε Hf value of −7.5 (not shown) and is presumably a xenocryst

Nd and Sr isotope methods for measurement of Long Valley rhyolites

A large amount of Nd and Sr isotope data for Long Valley rhyolites and their components exists (e.g., Christensen and Halliday 1996; Davies et al. 1994; Heumann and Davies 1997; Davies and Halliday 1998). For direct comparison, Nd isotope compositions (Table 2) were measured for the Bishop Tuff pumice samples for which Hf isotopes were collected and 40Ar/39Ar dating was performed. For completeness, Nd and Sr isotope measurements for a number of the studied rhyolites (Table 1) are also reported herein. For the Nd analysis, pumice and glass chips were powdered. Splits of the prepared powders of recently collected Bishop Tuff pumice samples (~100 mg) and previously measured pumice samples (~50 mg) were digested in HF-HClO4 mixtures on a hot plate. Standard ion chromatographic procedures were employed for element separation and Nd purification (e.g., DePaolo 1978). The new Nd isotope analyses were measured as atomic (Nd+) species assuming 146Nd/144Nd = 0.72190. The previously unpublished Nd isotope analyses were measured as either atomic or oxide (NdO+) species. In the latter case, it was assumed that 162NdO/160NdO = 0.724110. For intercomparison purposes, the sample data have been renormalized using atomic ratios following the approach described in (DePaolo 1988) in which 148Nd/144Nd = 0.243080. After renormalization the external reproducibly of the CIG, UC Berkeley internal standard measured between 2004-2009 is approximately 0.000013 (n = 43, 7 run specifically for this work), which is likely representative of the previous Nd studies. The typical uncertainty of individual Nd measurements is 0.000005 or ±0.1 ε (ε Nd), where ε Nd = 104 × ((143Nd/144Nd − 143Nd/144NdCHUR)/143Nd/144NdCHUR). A 143Nd/144Nd CHUR value of 0.511836 was used, based on 146Nd/142Nd = 0.636151. Instrumental Sr isotopic fractionation was corrected with an internal normalization of 86Sr/88Sr = 0.1194. The 86Sr/86Sr values reported herein are normalized to a SRM987 value of 0.710250. The details for Sr isotope analyses at CIG, UC Berkeley relevant to the previously unpublished Sr data reported for Long Valley rhyolites can be found in Bryce et al. (2005).

Systematic Hf and Nd isotopic variability recorded by Long Valley rhyolites

Hafnium isotopic compositions of seven single (~10 mg) and 40 groups (n = 2–20) of size-sorted (≤4.0 to ~0.3 mg) zircons, along with their respective whole rocks, were measured by MC-ICPMS analysis. Hafnium isotope measurements come from two Older Glass Mountain (GM) precaldera rhyolites, three pumice fragments from the Bishop Tuff (BT), and three postcaldera rhyolites (Table 2). All zircon grains were imaged prior to dissolution and analysis. Most were euhedual to subhedual and equant (Fig. 2). Zircons in the rhyolites record Hf isotopic compositions that broadly match the values found for their respective whole rocks, which show variable 176Hf/177Hf values (~1–3 ε Hf unit variations, see Fig. 2). In general, the Older GM rhyolites exhibit the lowest 176Hf/177Hf values in our sample suite, whereas late erupted BT (MR99LV51 and JS09MLV32) has a slightly higher 176Hf/177Hf value than the early erupted BT (MR99LV58). Postcaldera rhyolites vary in 176Hf/177Hf ratios from a slightly lower value up to nearly the same value observed for the late erupted BT (Fig. 2). Zircons found in the Older GM ~1,700 ka dome OD (MR00LV63) rhyolite display 176Hf/177Hf values equal to or lower than its inferred melt (i.e., whole rock) by up to ~3 ε Hf units. Most zircons from the ~780 ka BT have 176Hf/177Hf values equal to or higher than the host pumice. A few exceptions from both early and late erupted BT pumice exhibit values up to ~2 ε Hf units lower. The BT also contains rare xenocrystic zircon that is much less radiogenic (176Hf/177Hf = 0.28256) presumably originating from Mesozoic bedrock. Several younger (~575 and ~335 ka) postcaldera rhyolites from the North Moat (JS06MLV25) and Hot Creek flow (JS06MLV27) contain zircons with more primitive compositions (i.e., higher ε Hf) than their respective whole rocks. For example, the ~335 ka Hot Creek flow postcaldera rhyolite, which has the most primitive whole rock composition studied, contains a subpopulation of elongated zircon crystals with εHf values of ~4, the highest (most primitive, Fig. 2) measured in this study. We note that many of these grains had inclusions, but other relationships between morphology and Hf isotopic composition are absent (Fig. 2). By contrast, comparatively scarce zircon crystals from the ~675 ka Resurgent Dome flow rhyolite (JS06MLV026) fall into two zircon populations: one comprising large (~50–100 μm) grains with a 176Hf/177Hf composition lower (more evolved, Fig. 2) than nearly all other measurements in this study and a second population with values similar to the host whole rock composition.

Neodymium isotopic compositions of seven precaldera rhyolites, three pumice fragments from the BT, and thirteen postcaldera rhyolites (Table 1) were found to be similar to those by previous studies (e.g., Davies and Halliday 1998; Halliday et al. 1984, 1989) (see Fig. 6). Precaldera Older Glass Mountain rhyolites (−3.6 to −2.6 ε Nd) are more variable and distinct from precaldera Younger Glass Mountain rhyolites (~−1.0 ε Nd). Pumice fragments from both the early (MR99LV51 & B-104) and late (MR99LV51) erupted BT exhibit values that are more like those of the precaldera Younger rhyolites (−1.6 to −1.0 ε Nd). Postcaldera rhyolite whole rock Nd isotopes fall in between the values of the two groups of precaldera rhyolites and range to maximum values that are similar to the most primitive BT samples (~−1.0 ε Nd). As expected, secular variations in Nd isotope and Hf isotope compositions of the rhyolites are correlated (Table 1).

Initial Sr isotopic variability of Long Valley rhyolites

The range of measured Sr isotopic compositions (87Sr/86Sr = 0.706 to >0.8, Table 1) found in the studied Long Valley rhyolites is extreme and similar to those found by previous studies (e.g., Davies and Halliday 1998; Halliday et al. 1984, 1989). Much, but not all of this range is produced by radiogenic ingrowth. The high Rb/Sr compositions of Long Valley rhyolites require large age corrections (Table 1). The initial Sr isotope compositions (87Sr/86Sri = 0.70763–0.71900) of studied precaldera Older Glass Mountain rhyolites are distinct and more variable than precaldera Younger Glass Mountain rhyolites (87Sr/86Sri ~0.70650). A pumice fragment (B-104) from the early erupted BT exhibits a significantly higher value (87Sr/86Sri ~0.70898) than those of the Younger precaldera rhyolites and values reported by Davies and Halliday (1998) for the BT (87Sr/86Sri = 0.70600–0.70698). The variability found in the postcaldera rhyolites is greatly dampened as compared to the BT and precaldera rhyolites and progressively shifts toward rocks recording the most primitive Sr isotope compositions (87Sr/86Sri ~0.70600) found at Long Valley.

40Ar/39Ar dating of obsidian and feldspar

Most 40Ar/39Ar ages were obtain by laser heated individual or multi-grain feldspar analysis. In several cases, obsidian host glass was also dated. Only aphyric obsidian was dated for the sample (JS06MLV23) collected from the postcaldera North Moat flow rhyolite on the eastern flank of Lookout Mountain (Fig. 1). Feldspars were separated from crystal-poor obsidian, perlitic, and pumiceous glasses, concentrated by heavy liquid and magnetic separation techniques, and cleaned by short ultrasonic baths of dilute hydrofluoric acid followed by distilled water. Alkali feldspars were distinguished from plagioclase using immersion oils and petrographic methods, and each grain was then selected by hand for analysis. Obsidian samples were crushed to produce fragments of black glass, free of phenocrysts, and cleaned in distilled water with an ultrasonic bath. Two irradiations were used, the same ones used by Simon et al. (2009). The rhyolite materials, along with 91 Alder Creek feldspars (1,193 ± 1 ka; Nomade et al. 2005), used to monitor the neutron fluence, were irradiated at the Oregon State University TRIGA reactor in the Cd-lined CLICIT facility for 30 min within a series of stacked aluminum disks, permitting precise monitoring of both vertical and lateral (negligible) flux gradients (see supplementary Appendix for specifics). Total fusion and step-heating feldspar and glass analyses were performed. Individual and multi-grain feldspar aliquots and glasses were analyzed by laser step heating following procedures described previously (Nomade et al. 2005; and references therein). The 40Ar/39Ar results are summarized in Table 3. Grain size fractions, specific materials dated, and complete analytical details can be found in the supplementary Appendix. Age spectra derived from laser step heating of samples from previously dated domes show that excess 40Ar contamination likely biased some K–Ar results. However, 40Ar/39Ar analyses of the studied rhyolites with disturbed model ages (i.e., assuming atmospheric initial Ar), but well-defined Ar isochrons are considered to provide accurate eruption ages (Fig. 3). 40Ar/39Ar ages are calibrated per Renne et al. (2011), which intrinsically provides consistency with the 238U decay constant and thus facilitates comparison with U–Th–Pb ages.

40Ar/39Ar ages for feldspar and glass of the Bishop Tuff and selected postcaldera rhyolites. Sample names labeled in plots and their locations can be found in Fig. 1, except Bishop Tuff sample B77 that originated from Hildreth (1977). Inverse isochrons reflect combined total fusion and step-heating data from individual and multiple feldspar grain or obsidian analysis, as indicated. Error ellipses are 1σ. The thin-lined (red) data reflect those likely to have excess Ar∗ contamination and have been excluded from calculated age. See Table 3 and the complete data set found in supplementary Appendix

40Ar/39Ar eruption ages of Long Valley rhyolites

New 40Ar/39Ar ages were determined for nine rhyolites erupted from the Long Valley volcanic field (Table 3; Fig. 3). This work complements the 40Ar/39Ar dating of rhyolites reported by Davies et al. (1994), Heumann et al. (2002), Miller (1985), Simon et al. (2007), and Simon et al. (2008b). We used the same mass spectrometer at the Berkeley Geochronology Center, methods, and irradiations and carried out the experiments at essentially the same time as those published previously by Simon et al. (2007, 2008b). Previously determined ages for precaldera rhyolite domes OC (MR00LV60 and 61), OL (JS01LV05), OD (MR00LV63), YG (K–Ar age of Metz and Bailey (1993), and YA (JS01LV04); postcaldera rhyolite Deer Mountain; and Inyo Mono rhyolite South Deadman Dome have been included in Table 3 for completeness. All reported ages have been recalculated to the calibration of Renne et al. (2011). When possible and statistically plausible, results from multiple laser heating experiments were combined to define a more precise age for a given extrusion (see supplementary Appendix). The oldest rhyolite dated in the present study was the caldera-related Bishop Tuff. Inverse 40Ar/39Ar isochron ages defined by total fusion analysis of n = 24 and 26 individual sanidine grains for pumice fragments B77 (Hildreth 1977) and MR99LV51 (Simon and Reid 2005) yielded eruption ages of 780 ± 5 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 295 ± 1) and 781 ± 6 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 294 ± 1), respectively. A combined inverse isochron defined by sanidine from both pumice fragments yielded an age of 781 ± 5 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 294 ± 1). The combined weighted mean of the individual grains (n = 50) yielded a more precise age of 780 ± 2 ka. This age is indistinguishable from that of Sarna-Wojcicki et al. (2000) when the latter is recalculated per Renne et al. (2011), but significantly older than that of 767.4 ± 0.2 ka cited by Rivera et al. (2011). The oldest dated “Early” postcaldera rhyolites from the West Resurgent Dome (JS06MLV29 and 30) yielded ages of approximately 700 ka. Inverse isochrons defined by laser heating of two mineral separates of plagioclase from JS06MLV29 yielded consistent ages of 696 ± 40 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 309 ± 6) and 706 ± 25 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 302 ± 4). A third mineral separate yielded discordant 464 ± 50 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 340 ± 10) isochron, 529 ± 35 ka plateau, and 759 ± 120 ka integrated ages; these anomalous results may reflect laboratory contamination and are excluded from further consideration. A similar inverse isochron age for a plagioclase mineral separate from JS06MLV30 was determined to be 696 ± 45 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 303 ± 4) within error of the 666 ± 15 ka plateau age for the associated host glass. Laser step heating of obsidian (JS06MLV23) from Lookout Mountain, a North Moat rhyolite, yielded an age of 684 ± 9 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 297 ± 3). This age is within error of the 673 ± 14 ka K–Ar age of Bailey et al. (1976) for aphyric rhyolite (72G010) sampled from the same flow. An inverse isochron age defined by laser heating of a plagioclase mineral separate from a Resurgent Dome rhyolite (JS06MLV26) yielded a similar age of 676 ± 15 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 301 ± 4). This age appears to be older than the 634 ± 13 ka K–Ar age of Bailey et al. (1976) for pyroxene rhyolite (72G014) sampled from the same dome. A finer sized mineral separate of plagioclase yielded a consistent 686 ± 20 ka plateau age. A combined inverse isochron of both plagioclase mineral separates yielded an age of 676 ± 15 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 294 ± 3). An inverse isochron aged defined by laser heating of a plagioclase mineral separate from the South Resurgent Dome rhyolite (JS06MLV28) yielded an age of 656 ± 30 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 311 ± 3). This age is similar to the 675 ± 16 ka K–Ar age of Bailey et al. (1976) for aphyric rhyolite (72G001) sampled from the same flow. Two North Moat rhyolites (JS06MLV24 and 25) yielded distinctly younger ages of approximately 576 ka. Yet, both moat rhyolites are found to be significantly older than the 468 ± 11 and 509 ± 11 ka K–Ar ages reported by Bailey et al. (1976) for the corresponding hornblende-biotite rhyolites (72G011 and 72G012). Inverse isochron ages obtained for three different mineral separates of sanidine from JS06MLV24 yielded ages of 571 ± 10 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 295 ± 10), 585 ± 10 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 270 ± 20), and 579 ± 9 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 300 ± 15). The combined inverse isochron yielded the age of 576 ± 9 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 287 ± 7). An inverse isochron age defined by total fusion analysis of individual sanidine grains (n = 28) from JS06MLV25 yielded an age of 576 ± 7 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 297 ± 2). The companion inverse isochron age defined by step-heating analysis of a mineral separate of sanidine yielded an age of 585 ± 10 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 300 ± 4). The youngest rhyolite dated was the Hot Creek flow (JS06MLV27). An inverse isochron defined by one of three distinct mineral separates of sanidine yielded the age of 335 ± 6 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 294 ± 6). Plateau ages for two additional sanidine mineral separates and a duplicate split of the first mineral separate were 343 ± 4, 341 ± 3, and 338 ± 3 ka, respectively. A combined inverse isochron of all of the results yielded the age of 336 ± 2 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 298 ± 3), which is within error of an inverse isochron age for the host glass of 333 ± 15 ka (40Ar/36Ar = 294 ± 6).

U–Th–Pb dating of zircon by ion microprobe

Zircon grains were separated by heavy liquid techniques from crushed obsidian samples. U–Th–Pb dating was performed on individual zircon crystals using the UCLA CAMECA ims 1,270 secondary ion mass spectrometer (ion microprobe), similar to methods performed previously (Simon and Reid 2005). A <20–50 nA mass-filtered 16O−-beam was focused into a ~25–30 um oval spot. Secondary ions were accelerated at 10 keV with an energy bandpass of 50 eV and analyzed at a mass resolution of >4,800. The relative sensitivities for 238UO and 232ThO were calibrated by measuring the radiogenic 206Pb/208Pb ratio of concordant reference zircons AS-3 and 91500 (Paces and Miller 1993; Wiedenbeck et al. 1995). Individual U–Pb ages were 207Pb-corrected for common Pb using a measured whole rock initial common 207Pb/206Pb ratio of 0.818, typical of Long Valley rhyolites (Simon et al. 2007). The common lead composition is likely to be largely extrinsic, i.e., resulting from beam overlap with inclusions trapped within the host zircon, but could also be partly due to surficial contamination of the mounts by anthropogenic Pb, which for southern California has a similar composition (Sañudo-Wilhelmy and Flegal 1994). The 207Pb-corrected ages are also adjusted for initial U–Th disequilibrium due to the deficit in radiogenic 206Pb originating from the initial deficit in 230Th relative to 238U following Schärer (1984). The magnitude of this deficit can be estimated by comparing the Th/U ratios in zircon to those of the host magmas (i.e., glass). The absolute effect of this correction (typically adding 80–90 ka; Simon et al. 2008b) is accurate to ~10 ka, allowing for the range of whole rock Th/U ratios observed at Long Valley (e.g., Metz and Mahood 1991). Given the level of precision in which Pleistocene zircon ages and 40Ar/39Ar ages are now being performed, this uncertainty can be important and should not be ignored (cf. Crowley et al. 2007, see possible implications below).

U–Pb zircon age constraints on crystallization of postcaldera North Moat and Hot Creek flow rhyolites

Zircon ages reported here (Fig. 4) for the 336 ka Hot Creek flow (JS06MLV27) and the 576 ka North Moat (JS06MLV25) postcaldera rhyolites extend the results for zircon age populations determined previously for Long Valley rhyolites (Crowley et al. 2007; Reid and Coath 2000; Simon and Reid 2005; Simon et al. 2007). Although the apparent 365 ± 14 ka age for the zircon population (n = 13) found in the Hot Creek flow rhyolite is within error of its 40Ar/39Ar eruption age, the weighted mean yields a mean square of the weighted deviates (MSWD) = 4.45, exceeding that expected for a single age population. Zircon crystallization appears to have been protracted, with some growth possibly predating eruption by as much as ~115 ka. In contrast, the 613 ± 16 ka weighted mean age of zircon (n = 10) contained in the North Moat rhyolite yields an MSWD of 1.13 implying that crystallization largely occurred at the time of, or just preceding, eruption. The weighted mean zircon crystallization ages and associated values for the MSWD of the North Moat and Hot Creek flow zircon populations are summarized along side their respective 40Ar/39Ar eruption ages in Table 3; individual ages, U concentrations, and Th/U ratios for zircons analyzed in this study can be found in Table 4. Likewise, previously reported zircon ages of Reid et al. (1997), Simon and Reid (2005), and Simon et al. (2007) along with the new 40Ar/39Ar ages are included in Table 3. Estimates for model preeruption ages and for the duration of crystallization for all of the extrusions dated are given in Table 3, following the approach of Simon and Reid (2005). Because the MSWD of small data sets that are normally distributed around a single mean value may deviate from the expected value of unity, we also provide the MSWD values at the upper 95 % confidence interval on a single age distribution as defined by the degrees of freedom for each rhyolite.

Comparison of the distribution of U–Th–Pb zircon crystallization ages to Ar/Ar eruption ages for Hot Creek flow and North Moat postcaldera rhyolites. Circles indicate individual zircon measurements, solid line indicate the mean preeruption age (Hot Creek flow) or weighted mean age (North Moat), and shaded vertical band implies duration of zircon crystallization based on pooling older and younger ages, respectively (Table 1), for the Hot Creek flow rhyolite (see text for details). For each mean age, n gives the number of analyses. Dashed vertical lines show Ar/Ar eruption ages. All uncertainties are 1σ

Uranium concentrations of Hot Creek flow (~250–850 ppm) and North Moat (~200–2,700 ppm) zircons are typically lower than those found in the precaldera rhyolites and early erupted BT (that are mostly ~2,000 to >10,000 ppm), but more similar to those in the late erupted BT (Simon and Reid 2005; Simon et al. 2007). Moreover, the range of Th/U values recorded by zircon of these postcaldera rhyolites is greater than all but one of the precaldera rhyolites (dome OD) and similar to that observed for the BT (Fig. 5).

Th/U melt evolution recorded by studied Long Valley rhyolites (top) and zircon (bottom). Relatively narrow times where the range of Th/U compositions observed in zircon is large may indicate that these magmas evolved rather quickly (see text). Enlarged time interval shows Bishop Tuff zircon from Crowley et al. (2007) that postdate eruption and probably reflect an oversimplified U-series decay correction (see text)

Major and trace element compositions of Long Valley rhyolites

The major and trace element abundances of some studied Long Valley rhyolites were determined by XRF at UC Berkeley. Rubidium, Sr, Sm, and Nd abundances were determined by ID-TIMS at CIG, UC Berkeley. The XRF data (Table 1) were collected following established methods described in Wallace and Carmichael (1989). The compositions of Long Valley rhyolites have been reported previously (e.g., Heumann and Davies 1997; Hildreth and Wilson 2007; Metz and Mahood 1991). The results reported here are similar to those published previously, but come from samples and specific localities studied herein. All of the precaldera lavas are highly evolved high-silica rhyolites with 77–77.4 wt% SiO2 (e.g., Metz and Mahood 1985), typically about as evolved as the most evolved pumice from the Bishop Tuff (mainly ~74–77.7 wt% SiO2, Hildreth and Wilson 2007) and more evolved than many of the postcaldera rhyolites (~72 to ~76 wt% SiO2, Heumann and Davies 1997). Compositions of precaldera rhyolites are also less variable than those found in the Bishop Tuff and postcaldera rhyolites (see Fig. 8). A detailed account of the major and trace element compositions of Long Valley rhyolites is beyond the scope of this contribution. Here, we are primarily focused on chemical differences, in particular with respect to estimates of magma residence time, with the goal to understand the presumed genetic relationship(s) among Long Valley rhyolites. Both long-term trends and short-term fluctuations are present as can be seen in the representative examples in Figs. 5, 8, and 9, which show temporal variation among Th/U ratios, CaO wt%, and in La/Nd ratios, respectively.

Discussion

Previous work on the Long Valley Caldera system

Most studies of Long Valley rhyolites ultimately seek to understand the processes producing the cataclysmic Bishop Tuff magma(s). Below we discuss evidence for multiple compositionally distinct pre-Bishop magmas, whereby crystals from only the youngest of these magmas were incorporated into the caldera-related Bishop Tuff. Additionally, we discuss how the ages and compositions of post-Bishop magmas differed from those of the pre-Bishop and Bishop magma reservoirs and how the volcanic productivity at Long Valley appears to be related to changes in the amount of mantle-derived recharge to the system. The processes that have led to heterogeneity among Long Valley rhyolites, and in particular the Bishop Tuff, have been studied for over 30 years (e.g., Hildreth 1977; Hildreth and Wilson 2007). Melt compositions investigated by analysis of melt inclusions in phenocrysts and the phenocrysts themselves have provided important insights about the diversity of preeruptive magma bodies, in particular those of the Bishop Tuff (e.g., Anderson et al. 2000; Halliday et al. 1984; Hervig and Nelia 1992; Roberge et al. 2013; Wallace et al. 1999). Studies of the differentiation, and physical and thermal conditions of magmatic reservoirs at Long Valley (Davies and Halliday 1998; Davies et al. 1994; Halliday et al. 1989; Heumann and Davies 1997; Mahood 1990; Metz and Mahood 1985, 1991; Simon et al. 2007), preeruptive residence times of these magmas (Christensen and DePaolo 1993; Christensen and Halliday 1996; Crowley et al. 2007; Davies and Halliday 1998; Gualda et al. 2012; Reid and Coath 2000; Reid et al. 1997; Simon and Reid 2005; Simon et al. 2007; van den Bogaard and Schirnick 1995), and how they may relate to the production of rhyolite extrusions remain debated (e.g., Reid 2008; Simon et al. 2008b).

Isotopic heterogeneity among and within Long Valley rhyolites

Secular variations in Nd, Pb, Sr, and O isotopes have been documented for the Long Valley magmatic system (e.g., Bindeman and Valley 2002; Christensen and DePaolo 1993; Christensen and Halliday 1996; Davies and Halliday 1998; Davies et al. 1994; Halliday et al. 1989; Heumann and Davies 1997; Simon et al. 2007). These isotopic signatures potentially provide different perspectives to the history of Long Valley, including the evolution of it source compositions (i.e., Nd, Pb, and Sr isotopes), radiogenic ingrowth (Sr isotopes), and magma-thermometry (O isotopes). Each differs in detail, but broadly speaking all show a consistent trend where the magmatic system shifts from one that is dominated by a crustal source to one in which crustal magma reservoirs are spiked by influx of isotopically more primitive mantle-derived melts. The new Nd and Hf whole rock data are consistent with this general trend (Figs. 6, 7).

Nd isotope composition of whole rocks (filled symbols, this study) versus eruption age (ka) superimposed on existing data (other symbols) for Long Valley rhyolites. When possible, the Ar/Ar dating from Simon et al. (2007, Simon et al. 2008a, b, this study) was used for postcaldera rhyolites (green diamonds), precaldera rhyolites (blue diamonds), and Bishop Tuff (red squares). The exceptions include Ar/Ar dating of Davies and Halliday (1998) for late postcaldera (blue circles) and K–Ar dating of Bailey et al. (1976) for postcaldera rhyolites (orange diamonds). Bishop Tuff Nd data from Davies and Halliday (1998); Halliday et al. (1984) are shown by open squares. Precaldera Nd data from Davies and Halliday (1998) and Davies et al. (1994) plotted versus K–Ar ages (Bailey et al. 1976) shown with asterisks. Postcaldera Nd data and Ar/Ar data from Davies and Halliday (1998) plotted as “x’s,” which shows secular shifts in Nd over time periods of 100’s ka, but melt compositions likely changed more rapidly (10’s ka) perhaps continuously as indicated by ε Nd (e.g., Christensen and Depaolo 1993; Halliday et al. 1984) and ε Hf (this study, see Fig. 7) isotope heterogeneity found within their individual crystal populations

Hf isotope composition of whole rocks and zircon crystals versus eruption age (ka) for studied Long Valley rhyolites. Sample symbols shown in legend. Secular shifts in ε Hf over time periods of 100’s ka are observed, but melt compositions likely changed more rapidly (10’s ka) perhaps continuously as indicated by the ε Hf heterogeneity found within their individual zircon populations. Dashed arrows indicate approximate age span and sense of melt differentiation recorded by Th/U measurements from the dated zircon population of the studied rhyolites (Simon and Reid 2005; Simon et al. 2007; and this study)

Existing Nd, Pb, Sr, and O isotope crystal population studies of quartz and/or feldspars reflect evolution (e.g., increasing Nd, decreasing Pb, and Sr trends) toward mantle-derived signatures, in particular between the eruption of precaldera and late caldera-forming magmas, but greater heterogeneity is found at the mineral scale (Bindeman and Valley 2002; Christensen and Halliday 1996; Davies and Halliday 1998; Halliday et al. 1984, 1989; Heumann and Davies 1997; Simon et al. 2007). The Hf isotopic variability observed (ε Hf = ~−2 to ~4) among the studied zircon populations is also greater, but generally consistent with the secular isotopic shifts seen at the whole rock scale (Fig. 7). Previously, some mineral isotope compositions observed in younger extrusions have been used to suggest a direct co-genetic relationship between younger rhyolites, in particular the Bishop Tuff magma, to older precaldera rhyolite magmas at Long Valley. For example, model Rb–Sr ages calculated for the most radiogenic crystals are young enough (within ≤1,000 ka of their respective eruption) that they cannot be dismissed outright. Likewise some of these crystals appear to share Nd and Sr isotopic affinities with some older rhyolites (cf. Davies and Halliday 1998; Halliday et al. 1989; Mahood 1990; Simon et al. 2007). However, as discussed below, zircon dating studies are often at variance with these old model ages (e.g., Simon and Reid 2005). The zircon crystallization ages place a robust limit on the age and thus the possibility of a substantially older origin of the feldspars because dissolution of any putative old zircon would only occur under thermochemical conditions in the magma that would also lead to resorption of any accompanying feldspar. In addition, feldspar Sr and Pb isotopes conspicuously fall along crust–mantle mixing curves (see Fig. 5 of Simon et al. 2007). This implies that a component of the Sr isotopic variability is due to open-system interaction with preexisting crust (probably hydrothermally altered predecessors, Hildreth and Wilson 2007; Schmitt and Simon 2004; Simon et al. 2007) and not entirely to radioactive ingrowth. This is because unlike the Sr isotope variations in high Rb/Sr phases, Pb isotope differences cannot be explained by aging (cf. Wolff and Ramos 2003). Therefore, feldspars with radiogenic 87Sr-excesses may be antecrysts (e.g., Charlier et al. 2005)—crystals related to the system but not necessarily to the magma in which they are erupted.

Regardless of the Sr model ages being unreliable to constrain magmatic differentiation and residence, the fact that some crystals in the younger rhyolites share Nd isotopic affinities with the older rhyolites is still used as evidence for crystal carryover and thus appears to support claims for a long-lived interconnected magma body. Do these antecrysts originate from older rhyolitic magma reservoirs and thus support carryover of “crystal-cargo” from the older rhyolites, i.e., from the magma reservoir that produced Older Glass Mountain rhyolites to the Bishop Tuff magma? Akin to the isotopically heterogeneous feldspars, some zircon in the postcaldera rhyolites, i.e., the ~575 ka North Moat rhyolite (JIS06MLV026) and the Bishop Tuff have Hf isotope compositions that are similar to those observed in the precaldera Older Glass Mountain rhyolites. Notably, none of the zircon dated from postcaldera rhyolites or the Bishop Tuff (oldest grains are ≤900 ka) have ages that are as old as those from any of the Older Glass Mountain rhyolites (≥1,700 ka) (Simon and Reid 2005; Simon et al. 2007, and this study). Moreover, only a single U–Pb zircon analysis from the postcaldera ~575 ka North Moat rhyolite is old enough to have grown at the same time at which the Bishop Tuff magma(s) resided in the crust. These new data provide a link between the wealth of isotopic tracer and the geochronology studies and help to interpret the crystal record contained within individual eruptions. Based on their ages and Hf isotopic compositions, they imply little to no crystal carryover from older to younger magmas for both pre- and postcaldera magmas and suggest the existence of transient melt bodies throughout the life time of the system rather than the existence of a long-lived integrated magma chamber (Simon and Reid 2005). Hf isotopic variations among zircon contained within a single rhyolite can only be reconciled by the operation of open-system processes that are capable of shifting the 176Hf/177Hf ratio of the melt (ε Hf = 2–3) from which the zircons crystallized. Furthermore, the isotopic signatures in zircon provide a direct answer to the question of whether crystallization occurs before, during, or after mixing of crustal and mantle-derived components (Fig. 7). In the case of precaldera Glass Mountain dome OD (MR00LV63), most zircons crystallized from a melt that had a lower 176Hf/177Hf (more evolved) composition than the bulk rock, suggesting that the mantle component increased in the melt through time. In contrast, most zircons that crystallized in the Bishop Tuff and postcaldera rhyolites have 176Hf/177Hf compositions similar to and in some instances even higher (more mantle-like) than the bulk rock. The exceptions are the few anomalously low 176Hf/177Hf zircon crystals found in the 676 ka Resurgent Dome and Bishop Tuff rhyolites described above. Rhyolites dominated by zircon with 176Hf/177Hf compositions higher than their hosts are interpreted to reflect greater primitive magma influx during magma differentiation. The isotopically more mantle-like zircon likely crystallized from an initially more primitive melt before it was subsequently modified by contamination via crustal assimilation. In such a scenario, the bulk rock and the rare zircons with 176Hf/177Hf compositions lower than their host may reflect an evolving melt composition related to late stage partial assimilation of young silicic intrusions (Schmitt and Simon 2004), but not crystal carryover from a long-lived crystal mush.

A case can be made for relatively rapid melt differentiation given the relatively narrow zircon age populations found in the Bishop Tuff and ~576 ka North Moat rhyolites (see below). Because the scale of Hf isotopic variability among Long Valley rhyolites is too small to be resolved by current in situ laser ablation techniques (cf. Kemp et al. 2007), the sense of Hf isotope evolution during zircon growth and thus magma evolution cannot be determined directly. This can, however, be examined by looking at the evolution of melt (cf. Th/U ratios) recorded by the zircon crystal populations themselves which provide a proxy for the degree of differentiation (see Fig. 7 and discussed in detail below).

Magma residence time and the interpretation of Pleistocene rhyolite ages

Comparing U–Th–Pb and 40Ar/39Ar data sets such as those presented herein and reported previously (Crowley et al. 2007; Heumann et al. 2002; Reid and Coath 2000; Reid et al. 1997; Rivera et al. 2011; Sarna-Wojcicki et al. 2000; Simon and Reid 2005; Simon et al. 2007, 2008b) provides a more direct and arguably a more accurate means for determining the subvolcanic magma residence time span as compared to estimates based on the repose interval between eruptions (e.g., Spera and Crisp 1981) or those based on 40Ar/39Ar and Rb/Sr model ages (e.g., Christensen and DePaolo 1993; van den Bogaard and Schirnick 1995). At Long Valley, when compared to magma residence times estimated from 40Ar/39Ar contained in melt inclusions or Rb/Sr crystal model ages of 100’s to 1,000 ka, the zircon-based estimates are markedly shorter (i.e., ≤100’s of ka and not ≥500 ka). The relatively short (≤50–70 ka) magma residence time based on U–Th–Pb age determinations for zircon contained in the Bishop Tuff (e.g., Crowley et al. 2007; Reid and Coath 2000; Simon and Reid 2005) exemplifies this difference.

At face value, the preeruption time spans at Long Valley, which range from no resolvable time (e.g., Fig. 3 in this study) to 100’s ka (e.g., Reid et al. 1997; Simon and Reid 2005, this study), record the duration over which magmas were produced. In detail, the geologic significance of the preeruptive interval is less clear. It could reflect the storage interval of crystals growing in melt, i.e., a “magma residence” time. More specifically, these age spans may reflect minimum estimates of the time that magma was stored in the crust because the magmas were zircon-undersaturated (Watson and Harrison 1983) and/or resided in the deeper crust (cf. Dufek and Bergantz 2005) for parts of their history. Alternatively, the preeruption ages could reflect times where there was subvolcanic magma, but it is possible these zircons are unassociated with the erupted magma itself and thus not strictly related to its preeruption magma storage time. In terms of the unrelated crystals, the age spread would be due to remobilization of zircon from a collection of magmas, crystalline mushes, and/or subvolcanic plutons by the introduction of new melt. Although the process of partially remelting young intrusions may have contributed somewhat to the span of ages erupted for some zircon populations at Long Valley, it is unlikely that the observed protracted zircon crystallization interval simply reflects the remobilization from just a couple of short-lived (<10’s ka) granitic intrusions that extruded the Older and Younger Glass Mountain rhyolites, respectively, as envisioned by Sparks et al. (1990).

Age constraints for the climactic Bishop Tuff

Comparing the 40Ar/39Ar and U–Th–Pb ages of a rhyolite to determine its magma residence time has historically been complicated by uncertain intercalibration between these two chronometers (e.g., Channell et al. 2010; Kuiper et al. 2008; Min et al. 2000; Rivera et al. 2011). Although this uncertainty has little direct bearing on the main conclusions of this study, the age of the Bishop Tuff (cf. Channell et al. 2010; Crowley et al. 2007; Renne et al. 2010; Rivera et al. 2011; Simon et al. 2008a) has become central to this issue and to magma generation timescales in general. Crowley et al. (2007) determined a precise weighted mean zircon U–Pb age of 767 ± 0.5 (n = 17/19) by chemical abrasion isotope dilution thermal ionization mass spectrometry (ID-TIMS). At face value, this age appears to be compatible with the slightly younger mean 759 ± 2 ka (n = 70) 40Ar/39Ar eruption age reported by Sarna-Wojcicki et al. (2000) and indistinguishable if this age is recalculated to 770 ± 2 ka using the calibration of Renne et al. (1998) as was done by Crowley et al. (2007). However, this apparent consistency disappears if the 40Ar/39Ar age of Sarna-Wojcicki et al. (2000) is recalculated (~778 ka) using the optimized calibration of Renne et al. (2011). Other recently proposed 40Ar/39Ar calibrations (Channell et al. 2010; Rivera et al. 2011) yield younger ages for the Bishop Tuff and thus appear to eliminate the apparent conundrum of zircon forming after the eruption. However, these new calibrations are mutually incompatible, and therefore, either one or both must be wrong (Renne 2013). The new 40Ar/39Ar age in this study of 780 ± 2 ka (using the calibration of Renne et al. 2011) for sanidine extracted from two pumice clasts (n = 50) is consistent with the measurements of Sarna-Wojcicki et al. (2000) when normalized to the same calibration. Rivera et al. (2011) also report a new 40Ar/39Ar age for the Bishop Tuff (767.4 ± 1.1 ka, n = 14/15) based on their own astronomically calibrated age of 28.172 Ma for the Fish Canyon Tuff sanidine (FCs) standard. The difference between our ages for the Bishop Tuff and those of Rivera et al. (2011) is not solely a result of the different calibrations used. Renne (2013) showed that the Rivera et al. (2011) data and those of Sarna-Wojcicki et al. (2000) are analytically distinct, with R values (40Ar × /39Ar of the Bishop Tuff sanidine relative to that of the FCs standard) of 0.02706 ± 0.0005 and 0.02728 ± 0.00007, respectively. Our new data presented here yield an R value of 0.02736 ± 0.00007, agreeing with that of Sarna-Wojcicki et al. (2000) but not Rivera et al. (2011). Thus, we have a large number of replicates (n = 120) from multiple samples of Bishop Tuff analyzed in two laboratories that yield internally consistent results, and these are analytically distinct from results obtained from a single sample in one laboratory (n = 15). Our data pooled with those of Sarna-Wojcicki et al. (2000) yield a weighted mean R value of 0.02732 ± 0.00006. Using either of the astronomical ages ascribed to FCs by Rivera et al. (2011) or Kuiper et al. (2008) and consistent with the ID-TIMS data of Wotzlaw et al. (2013), this R value translates to ages of 775 ± 2 or 776 ± 2 ka, respectively. Thus, even using the youngest modern calibration of the 40Ar/39Ar system applied to the most coherent 40Ar/39Ar data for the Bishop Tuff yields an age distinctly older than the inferred U–Pb zircon age of Crowley et al. (2007). We believe that the zircon U–Pb ID-TIMS age likely reflects an oversimplified U-series disequilibrium correction, to which Pleistocene U–Pb zircon ages are highly sensitive. The 206Pb*/238U system requires a disequilibrium correction of typically 6–15 % or roughly 80–90 ka for the age of the Bishop Tuff (Schärer 1984; Simon et al. 2008a, b). One of the variables involved in the correction is the Th/U value of the host melt. The Th/U estimate for a compositionally heterogeneous (i.e., evolving) magma body is difficult to define and can have a relatively large effect on the absolute age and its uncertainty. The crystallization of zircon and other accessory phases (e.g., allanite) can have a large effect on the residual Th/U (melt) value (cf. Fig. 7 of Heumann et al. 2002). It follows that the mean Th/U (melt) value of 2.81 ± 0.16 (1 s) used by Crowley et al. (2007) from a subset of the published data for quartz-hosted melt inclusions (Anderson et al. 2000) may not represent the melt composition from which the dated zircon grew. This point is further emphasized by considering the much wider range of pumice whole rocks compositions reported (i.e., Th/U (melt) = 3.1–5.1 of Hildreth 1977, Fig. 5). It is therefore appropriate to question the validity of whether relatively late forming quartz would trap melt that represents the composition from which the dated zircon grew. Furthermore, the Th/U (melt) value employed by Crowley et al. (2007) likely does not adequately represent the host melt because melt inclusions in quartz phenocrysts vary more greatly than the range that they considered (i.e., Th/U ~1.5–4.1, Schmitt and Simon 2004) and generally record more evolved magma than the whole rock pumice. In fact, a greater range and generally lower Th/U are observed in melt inclusions, whether or not the quartz crystals were derived from an early evolved or a late less evolved melt, i.e., pumice whole rock clast (Schmitt and Simon 2004). If the average pumice Th/U (melt) composition from Hildreth and Wilson (2007) of 3.5 (n = 424) is used, the weighted mean age for the zircon ID-TIMS data increases to ~771 ka and if a Th/U (melt) composition of 4.5, similar to that found in many of the late erupting pumice, is assumed the ID-TIMS age becomes ~775 ka. Both are within error of the preferred 40Ar/39Ar eruption ages (Sarna-Wojcicki et al. 2000; this study). Further analysis of the discrepancies between various 40Ar/39Ar sanidine and ID-TIMS U–Pb zircon ages for the Bishop Tuff would be fruitful in general, but is beyond the scope of this paper.

In addition to the discrepancy between the 40Ar/39Ar and U–Pb ID-TIMS ages as reported, there are obvious differences between the published ID-TIMS and secondary ion microprobe (SIMS) zircon ages, namely the wealth of SIMS data that imply that zircons begin to crystallize around 830–850 ka ago in the Bishop Tuff magma (Reid and Coath 2000; Simon and Reid 2005). Next, we summarize concerns and differences in these data sets and offer plausible explanations. Zircon crystals saturate early (i.e., near the liquidus) in metaluminous rhyolite magmas and therefore likely record the changing melt composition over a protracted temperature interval. For this reason, individual zircon crystals are often zoned (both compositionally and with respect to age). In fact, zoning in Bishop Tuff zircon is well established by various analytical approaches (e.g., Crowley et al. 2007; Reid and Coath 2000; Reid et al. 2011; Simon and Reid 2005).

Simon et al. (2008b) considered the effect of unrecognized heterogeneity (i.e., older cores) when dating individual zircon grains. These considerations are the same whether the heterogeneity (i.e., zoning) is magmatic or due to inheritance. The geometric and compositional effects on the accuracy of individual zircon ages, due to age and compositional zoning, can be found in Simon et al. (2008b). This forward modeling approach quantitatively shows how the mean ages (e.g., obtained by ID-TIMS) will be weighted toward younger ages because of the greater volume of late, often U-rich, growth measured. In contrast, most SIMS ages, and certainly those reported for Long Valley rhyolites (i.e., R99LV58 that yields a mean age = 841 ± 8 ka, MSWD = 0.9, n = 29; 061498-24-6 that yields a mean age = 822 ± 10 ka, MSWD = 0.9, n = 22; and R99LV51 that yields a mean age = 810 ± 7 ka, MSWD = 3.3, n = 20, from Reid and Coath 2000 and Simon and Reid 2005), are obtained from spots with lateral dimensions of ~20 μm in diameter which were placed within the core of zircons. Even when crystals rims were targeted, the beam overlap with interior domains will bias the SIMS age toward the crystal interiors, whereas a significant volume of zircon in the crystal rims will be underrepresented unless alternative SIMS techniques are applied (e.g., depth profiling; Reid and Coath 2000). Thus, zoning that has been measured in Bishop Tuff zircon (Simon and Reid 2005) helps to explain the apparent difference between the older mean age and significant age spread determined by SIMS and the younger ages based on the more limited number, but more precise ID-TIMS zircon analyses. Considering both the sampling differences between SIMS and ID-TIMS (and the likely bias toward the outer high [U] and younger ages in the ID-TIMS work) and the more realistic uncertainty that should be assigned to the ID-TIMS ages, the apparent disparity between 40Ar/39Ar eruption, the precise ID-TIMS, and older zircon SIMS (core) ages can all be reconciled.

Ages for other Long Valley rhyolites

At Long Valley, zircon age populations have been reported for a number of rhyolite extrusions in addition to the Bishop Tuff (Heumann et al. 2002; Reid et al. 1997; Simon and Reid 2005; Simon et al. 2007, 2008b). Zircon ages have been measured in five of the precaldera Glass Mountain domes and show no evidence for inheritance of zircons older than the Long Valley magmatic system (Simon and Reid 2005). In all five Glass Mountain rhyolites, the zircon crystallization ages range from tens to hundreds of ka before eruption and generally support the inference of 10’s–100’s ka preeruption magma residence times. In more detail, the mean preeruption ages of the 2,059 ka Glass Mountain (GM) OC dome is 2,301 ± 15 ka (MSWD = 1.85, n = 13), the 1,939 ka GM OL dome is 2,153 ± 15 ka (MSWD = 2.03, n = 11), the 1,699 ka GM OD dome is 1,904 ± 15 ka (MSWD = 1.31, n = 20), the 916 ka GM YG dome is 984 ± 22 ka (MSWD = 1.46, n = 10), and the 875 ka GM YA dome is 999 ± 19 ka (MSWD = 2.16, n = 9). From oldest to youngest, these zircon age populations imply progressively decreasing residence time (τ) of 244 ± 25, 214 ± 28, 205 ± 26, 68 ± 43, and 123 ± 24 ka, respectively (cf. the SIMS zircon age population measured in the Bishop Tuff imply τ ~50 ± 10 ka).

The new U–Th–Pb SIMS zircon ages reported herein for postcaldera rhyolites complement the pioneering work of Heumann et al. (2002) and Reid et al. (1997) for some of the most recent eruptions at Long Valley caldera, including the 0.6 ka South Deadman Dome, the 102 ka Deer Mountain, the 110 ka Mammoth Knolls, and the ~153 ka Low Silica Rhyolite flow. At face value, the new zircon ages measured in the 336 ka Hot Creek flow rhyolite (JS06MLV27) and the 576 ka North Moat rhyolite (JS06MLV25) exhibit mean U–Th–Pb zircon ages that are within error of their respective eruptions. The precision of U–Th–Pb zircon ages over the ~250–400 ka age range is compounded by their low amount of 206Pb radiogenic ingrowth and the comparatively large U-series disequilibrium age correction. Nevertheless, the relatively high goodness-of-fit parameter (MSWD = 4.45) and calculated mean preeruption age of 490 ± 25 ka (n = 12) indicate that the Hot Creek flow rhyolite contains zircon that may have predated eruption by as much as 154 ± 27 ka. Unlike the Hot Creek flow and other young Long Valley rhyolitic extrusions that exhibit significant preeruption crystallization age populations (from ~30 ka in the Mammoth Knolls to ~200 ka for Deer Mountain rhyolites, Heumann et al. 2002; Reid et al. 1997), there is minimal evidence for preeruption magma residence or a resolvable differences among zircon ages in the 576 ± 7 ka North Moat rhyolite (mean zircon age is 613 ± 16, MSWD = 1.13, n = 10).

The 102 ka Deer Mountain Dome is the only rhyolite at Long Valley beside the Bishop Tuff where both SIMS and ID-TIMS zircon age determinations have been reported (Heumann et al. 2002; Reid et al. 1997), albeit by U–Th not U–Th–Pb dating. Both approaches suggest that the Deer Mountain magma underwent protracted crystallization. Analogous to differences observed among Bishop Tuff zircon measurements, the weighted mean preeruption age (194 ± 7 ka, n = 10) derived from SIMS analysis is less precise than the ID-TIMS zircon-glass model age (254 ± 3.5 ka). Furthermore, the Th/U compositions determined for zircon by SIMS range from slightly lower values to values that are a factor of ~2 greater than determined by ID-TIMS. We suspect that this is a similar case where much of the temporal and compositional variability contained in the zircon record has been obscured by mixing over multiple crystal domains, as we have discussed in the comparison between Bishop Tuff ID-TIMS and SIMS U–Pb zircon ages. Heumann et al. (2002) interpret the preeruptive zircon U-Th model age as indicative of protracted magma residence time. This interpretation is consistent with the SIMS U-Th measurements of individual zircons in this dome (Reid et al. 1997).

Except for one model U–Th zircon age at ~30 ka, and a couple at ~100 ka, most zircons dated from the 0.6 ka South Deadman Dome rhyolite cluster around 175–250 ka (see Figure 3 of Reid et al. 1997), significantly older than the age of eruption. Reid et al. (1997) considered the possibility that apparent age gaps between ~100 and ~30 ka and then to 0.6 ka reflect remobilization of a near or completely solidified leucogranite. They ultimately argued that the chemical affinities between the South Deadman Dome and Deer Mountain Dome rhyolites and the euhedral zircon are more consistent with residence in a common long-lived magma reservoir. As suggested previously for these protracted zircon age populations (Reid et al. 1997) and discussed more generally below in order to maintain magmatic temperatures for periods of 10’s ka, there must be an additional heat source (e.g., Annen 2009). The wealth of isotopic heterogeneity found among the Long Valley rhyolites and among the zircon crystals that they contain (this work) implies open-system evolution and supports the hypothesis that this thermal influx could be provided by intrusion of less evolved magmas (e.g., Christensen and DePaolo 1993; Heumann and Davies 1997; Simon et al. 2007).

In summary, the comparison between zircon ages and 40Ar/39Ar eruptions ages for representative rhyolite extrusions from the precaldera, caldera, and postcaldera periods often exhibit significant preeruption crystallization (Fig. 11). The magmas that erupted prior to caldera collapse appear to show a secular decrease in their apparent magma residence times over time (Simon et al. 2007). This trend may continue through eruption of the caldera-related Bishop Tuff and to some of the earliest rhyolites in the postcaldera period (i.e., North Moat rhyolite appears to have negligible preeruption zircon growth, this study). After this point in time, there seems to be a reversal in the preeruption crystallization periods, in which they expand again as the system evolves, back to time spans that are comparable to the precaldera Older Glass Mountain rhyolites (see inset in Fig. 11). Possible explanations for this trend, such as it is, are discussed below, but it is not one that can be easily predicated by volume-frequency arguments (Crisp 1984). In fact, the volume and preeruption time period appear to reflect an inverse correlation (cf. Simon et al. 2008b). Long Valley rhyolites exhibit variable magma residence times, and as discussed next, likely reflect external parameters (e.g., varying mantle-derived mafic magma input).

Temporal constraints for geochemical trends found among Long Valley rhyolites

The whole rock compositions of Long Valley rhyolites define a coherent fractional crystallization differentiation trend (see the inset of Fig. 8 showing CaO vs. TiO2). Yet, the temporal eruption sequence of the Long Valley rhyolites (Fig. 8), and the isotopic heterogeneities, invalidates such a simple scenario. Likewise, the major element trends observed in the younger rhyolites (<400 ka) clearly show that progressive differentiation of a single magma body is unrealistic. Another possibility based on the varying major element data is that the extrusions erupted between ~2,050 to ~600 ka reflect downward extraction from a zoned long-lived magma body (i.e., the long-lived “mush model” magma chamber), inverting the compositional zoning with sequential eruption. However, as discussed above and supported by results in Crowley et al. (2007), Simon and Reid (2005), Simon et al. (2007), and this study, the discrete crystal populations and virtual lack of zircon carryover does not support this scenario. Rather, the zircon studies indicate that the extrusions are the result of transient melts that represent discrete episodes of silicic magma genesis.

CaO whole rock compositions versus eruption age (ka) for Long Valley rhyolites. Sample symbols shown in legend. Major element trends from ~2,050 to ~600 ka have been interpreted to reflect downward extraction from a zoned magma body, inverting the compositional zoning of the magma chamber with sequential eruption. Younger rhyolites (<400 ka) show that simple differentiation of a single large magma body is unlikely. Without the temporal constraints CaO versus TiO2 whole rock data (inset) also appear to show a coherent differentiation trend. For reference, the range outlined in red represents a majority of Bishop Tuff pumice compositions from Hildreth and Wilson (2007), which is greater than originally reported, although these pumice are never as evolved as the most evolved precaldera rhyolite compositions

Variations of some trace elements follow the coherent differentiation trends of the major elements. For example, trace element contents reflecting fractionation involving phenocrysts minerals (primarily quartz, feldspar, biotite, ±pyroxene) such as Rb, Ba, and Sr in the postcaldera rhyolites (Heumann and Davies 1997; this study) are consistent with major element compositions being chemically less evolved relative to the precaldera rhyolites (Davies et al. 1994; Metz and Mahood 1991). However, the abundances of some trace elements like the REEs and the high field strength elements (e.g., Zr, Th, U, and Nb) that are controlled by accessory minerals (zircon, allanite, and apatite) require at least two differentiation paths (Davies et al. 1994; Heumann and Davies 1997; Metz and Mahood 1991; this study Fig. 9). Previous studies have argued that REE variations (e.g., La/Sm), especially those observed over the time period between the ~700 and the ~336 ka Hot Creek flow eruptions, would require fractionation of accessory minerals or mafic minerals like amphibole in percentages that exceed those present in the rocks. These studies conclude that either two distinct magma systems existed or portions of a large stratified body evolved independently at that time (Heumann and Davies 1997). In allanite-saturated rhyolites from Toba (Sumatra) and Coso (California), compositional shifts toward higher La/Nd have been related to input of more mafic magma (e.g., Vazquez and Reid 2004; Simon et al. 2009). Addition of evolved magma and/or intrusions where allanite saturation has not occurred could also drive up La/Nd values, i.e., that possibly exists among the Mesozoic granitoids (Fig. 9). The latter would be consistent with the observed coeval drop in Nd and Hf isotope compositions that imply addition of more crustal material (Figs. 6, 7).

La/Nd ratio versus eruption age (ka) for Long Valley rhyolites. Inset shows La/Nd ratio versus Zr/Nb ratio. Sample symbols shown in legend. REE and high field strength elements show at least two differentiation trends (black arrows). Not shown are the high values of Deer Mountain (~6.3; Heumann and Davies 1997) and an early postcaldera rhyolite (4.3; Metz and Mahood 1991). Bishop Tuff data include those reported by Hildreth (1977); Hildreth and Wilson (2007), open squares; and this study, red square

A detailed record of the melt evolution can potentially be found in the accessory minerals themselves. Here, we evaluate the Th/U ratios in zircon (Fig. 5, bottom plot) which is potentially controlled by thermally and compositionally controlled saturation of accessory mineral, although we cannot rule out the effects of variable oxygen fugacity in the melt (e.g., Burnham and Berry 2012). The range of Th/U compositions observed in zircon contained in the postcaldera rhyolites reported herein is similar to the range observed in zircon reported for other postcaldera rhyolites (Reid et al. 1997) and the Bishop Tuff (Reid and Coath 2000; Simon and Reid 2005), but exceeds that of all but one of the previously studied precaldera rhyolites (i.e., dome OD) (Simon and Reid 2005). This increased compositional range coupled with relatively brief zircon age spans may indicate that the subvolcanic magma systems that produced the Bishop Tuff and early postcaldera rhyolites were derived from magmas that evolved rather quickly. The similar range of Th/U values, but longer magma residence time recorded by zircon contained in the youngest postcaldera rhyolites (i.e., Deer Mountain and South Deadman Dome), suggests that these magmas may have also evolved quickly, but were stored longer prior to their eruption. In contrast, the protracted age populations, their reduced Th/U variability, and the lower Th/U values characteristic of zircon contained in the precaldera Glass Mountain rhyolites indicate that once they were generated, the precaldera magmas underwent only moderate amounts of differentiation. The 1,699 ka dome OD Older Glass Mountain rhyolite is the exception. It exhibits a degree of variability in Th/U values similar to many of the postcaldera rhyolites and the Bishop Tuff.

The overall evolution of the Long Valley magma system as reflected in the variation of zircon Th/U values can be subdivided into three stages: (1) precaldera Older Glass Mountain rhyolites ending with the 1,699 ka precaldera dome OD, (2) precaldera Younger Glass Mountain rhyolites ending with the ~700 ka postcaldera rhyolites (including the Bishop Tuff), and (3) postcaldera 336 ka Hot Creek flow expanding up until at least extrusion of the 102 ka Deer Mountain Dome and possibly to the 0.6 ka South Deadman Dome. These stages initiate with zircon crystallizing with comparatively low and homogeneous Th/U values (Fig. 5). The onset of these stages also correlates with prominent discontinuities in Nd and Hf isotopes with increases in ε Nd and ε Hf indicating the production of less evolved rhyolites either due to greater input of mafic, presumably mantle-derived, magma into the crust diluting the crustal component or from greater input of less evolved melt from the lower crust. Notably, while the oldest zircon crystals contained in the ~336 ka Hot Creek flow overlap in age with most of the zircon crystals contained in the ~576 ka postcaldera rhyolite, the range at that time in each Th/U is at their least and most (Figs. 4, 5), respectively, for the two extrusions implying that these magma bodies coevolved for a time, but were unlikely interconnected.

The thermal evolution of Long Valley magma reservoir(s)

Knowledge of the thermal evolution of the Long Valley magma system, in particular the supervolcanic Bishop Tuff magma(s), has important physical implications for understanding the evolution of its volcanic behavior. Eruption temperatures (i.e., derived from coexisting Fe–Ti oxide pairs) are expected to be equal to or less than crystallization temperatures, although reversals are reported elsewhere (e.g., Simon et al. 2009). In general, there are limitations to establishing a robust geothermometry based on coexisting mineral assemblages for Long Valley rhyolites (e.g., Evans and Bachmann, 2013), in part because of the crystal-poor nature of the rocks, the possible exceptions being the Bishop Tuff (Hildreth 1977) and a short list of precaldera rhyolites (Metz and Mahood 1991). Here, we focus on zircon saturation temperatures (TZr) that we calculated from whole rock compositions and Zr contents of the studied rhyolites following the approach of Watson and Harrison (1983) and the recalibration by Boehnke et al. (2013) (Fig. 10). Additional magma temperature estimates come from oxygen isotope thermometry (Chiba et al. 1989), Ti-in-zircon (Watson et al. 2006), and Ti-in-quartz (Wark and Watson 2006) geothermometers. Using the new calibration of Boehnke et al. (2013), the TZr for Bishop Tuff pumice (~melt) compositions that range continuously from ~665 to 750 °C with a median of 695 °C (n = 424) (Hildreth and Wilson 2007) is significantly lower than those estimated from Ti-in-quartz (720–810 °C, Wark et al. 2007), oxygen Δ18O (qz-mt) fractionation (715–815 °C, Bindeman and Valley 2002), and eruption temperatures derived from Fe–Ti oxide pairs (714–798 °C, Hildreth and Wilson 2007). The lower zircon saturation and higher eruption temperatures resulting from these different geothermometers are surprising given the geological processes that they are conventionally thought to reflect (i.e., zircon crystallization and near-eruption melt temperature, respectively). Based on the thermodynamic analysis of Ghiorso and Gualda (2012), the titania activity derived from Fe–Ti oxide pairs reported for the Bishop Tuff is orthogonal to the trend expected of oxide–melt equilibrium upon cooing of a magmatic system. Ghiorso and Gualda (2012) therefore suggested that the Fe–Ti oxide temperature estimates for the Bishop Tuff likely do not record preeruptive conditions (i.e., near-eruption temperatures), but rather may imply reequilibration. In addition, Reid et al. (2011) find that the apparent Ti-in-zircon crystallization temperatures determined for the Bishop Tuff are more restricted (ΔT ~30–40 °C) and more similar (<720 °C) to the recalibrated zircon saturation temperature estimates. The similarity between a majority of the zircon saturation temperatures and the Ti-in-zircon crystallization temperatures is increased if realistic pressure corrections are included in the Ti-in-zircon calculations. Moreover, because of recent evidence for enhanced solubility of Ti in quartz at upper crustal pressures (Thomas et al. 2010), the reported Ti-in-quartz temperature estimates may also be too high (Reid et al. 2011). Collectively, a limited range of zircon temperatures is more consistent with the idea that the Bishop Tuff was derived primarily from remelted subvolcanic intrusions by the recharge of hotter magmas rather than from a long-lived, cooling, and evolving magma body. Moreover, remelting of solidified intrusions, rather than remobilization of a consolidated crystal mush, is our preferred interpretation because of the apparent lack of zircon carryover from the precaldera rhyolites and the evidence for assimilation of young hydrothermally altered intrusions reported by Schmitt and Simon (2004).